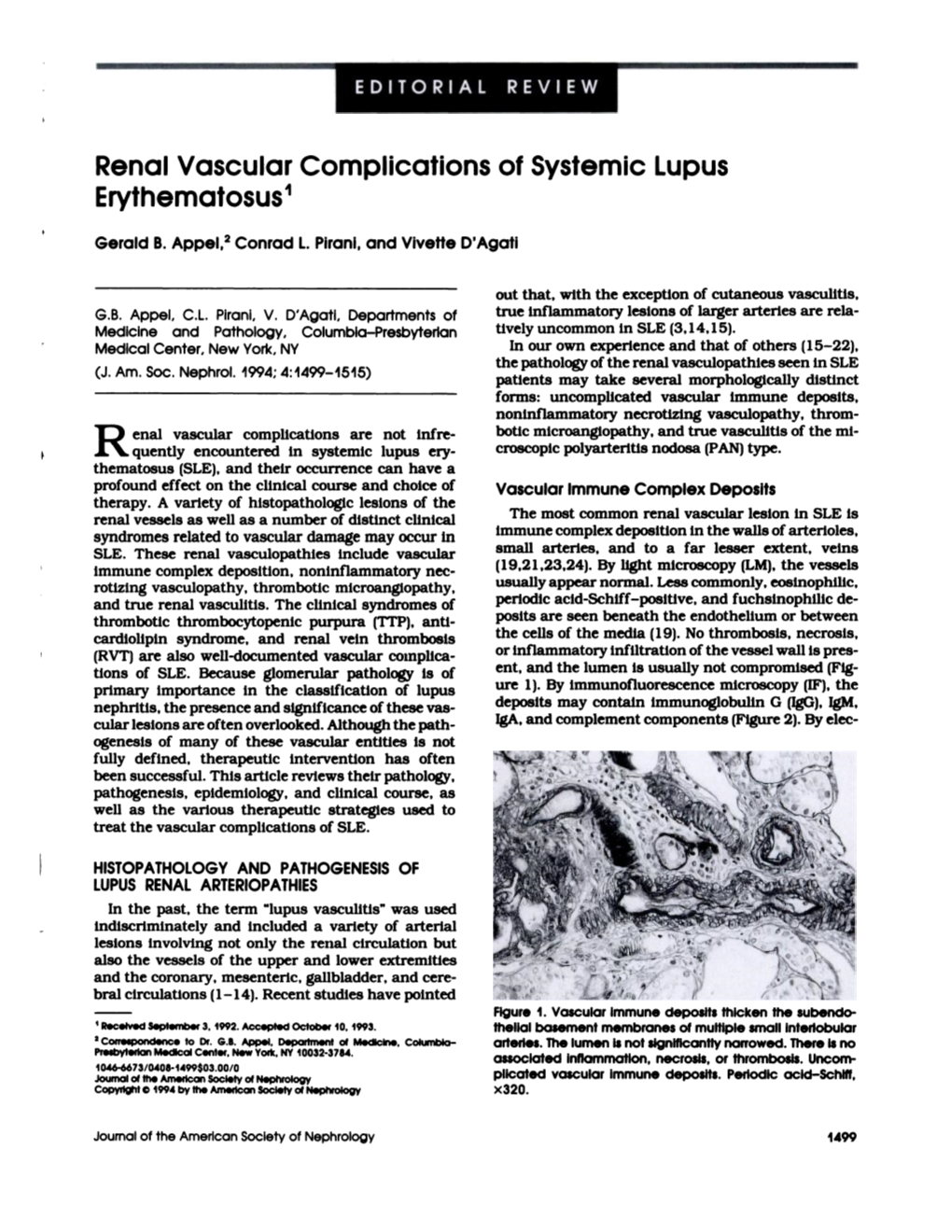

Renal Vascular Complications of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autoimmune Associations of Alopecia Areata in Pediatric Population - a Study in Tertiary Care Centre

IP Indian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 2020;6(1):41–44 Content available at: iponlinejournal.com IP Indian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dermatology Journal homepage: www.innovativepublication.com Original Research Article Autoimmune associations of alopecia areata in pediatric population - A study in tertiary care centre Sagar Nawani1, Teki Satyasri1,*, G. Narasimharao Netha1, G Rammohan1, Bhumesh Kumar1 1Dept. of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprosy, Gandhi Medical College, Secunderabad, Telangana, India ARTICLEINFO ABSTRACT Article history: Alopecia areata (AA) is second most common disease leading to non scarring alopecia . It occurs in Received 21-01-2020 many patterns and can occur on any hair bearing site of the body. Many factors like family history, Accepted 24-02-2020 autoimmune conditions and environment play a major role in its etio-pathogenesis. Histopathology shows Available online 29-04-2020 bulbar lymphocytes surrounding either terminal hair or vellus hair resembling ”swarm of bees” appearance depending on chronicity of alopecia areata. Alopecia areata in children is frequently seen. Pediatric AA has been associated with atopy, thyroid abnormalities and a positive family history. We have done a study to Keywords: find out if there is any association between alopecia areata and other auto immune diseases in children. This Alopecia areata study is an observational study conducted in 100 children with AA to determine any associated autoimmune Auto immunity conditions in them. SALT score helps to assess severity of alopecia areata. Severity of alopecia areata was Pediatric population assessed by SALT score-1. S1- less than 25% of hairloss, 2. S2- 25-49% of hairloss, 3. 3.S3- 50-74% of hairloss. -

Coexistence of Vulgar Psoriasis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus - Case Report

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.1679-9836.v98i1p77-80 Rev Med (São Paulo). 2019 Jan-Feb;98(1):77-80. Coexistence of vulgar psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus - case report Coexistência de psoríase vulgar e lúpus eritematoso sistêmico: relato de caso Kaique Picoli Dadalto1, Lívia Grassi Guimarães2, Kayo Cezar Pessini Marchióri3 Dadalto KP, Guimarães LG, Marchióri KCP. Coexistence of vulgar psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus - case report / Coexistência de psoríase vulgar e lúpus eritematoso sistêmico: relato de caso. Rev Med (São Paulo). 2019 Jan-Feb;98(1):77-80. ABSTRACT: Psoriasis and Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) RESUMO: Psoríase e Lúpus eritematoso sistêmico (LES) são are autoimmune diseases caused by multifactorial etiology, with doenças autoimunes de etiologia multifatorial, com envolvimento involvement of genetic and non-genetic factors. The purpose de fatores genéticos e não genéticos. O objetivo deste relato of this case report is to clearly and succinctly present a rare de caso é expor de maneira clara e sucinta uma associação association of autoimmune pathologies, which, according to some rara de patologias autoimunes, que, de acordo com algumas similar clinical features (arthralgia and cutaneous lesions), may características clínicas semelhantes (artralgia e lesões cutâneas), interfere or delay the diagnosis of its coexistence. In addition, it podem dificultar ou postergar o diagnóstico de sua coexistência. is of paramount importance to the medical community to know about the treatment of this condition, since there is a possibility Além disso, é de suma importância à comunidade médica o of exacerbation or worsening of one or both diseases. The conhecimento a respeito do tratamento desta condição, já que combination of these diseases is very rare, so, the diagnosis existe a possibilidade de exacerbação ou piora de uma, ou de is difficult and the treatment even more delicate, due to the ambas as doenças. -

Table of Contents (PDF)

CJASNClinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology October 2018 c Vol. 13 c No. 10 Editorials 1451 Metabolic Acidosis and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in CKD Matthew K. Abramowitz See related article on page 1463. 1453 Beware Intradialytic Hypotension: How Low Is Too Low? Jula K. Inrig See related article on page 1517. 1455 PD Solutions and Peritoneal Health Yeoungjee Cho and David W. Johnson See related article on page 1526. 1458 Proton Pump Inhibitors in Kidney Disease Benjamin Lazarus and Morgan E. Grams See related article on page 1534. 1460 Inching toward a Greater Understanding of Genetic Hypercalciuria: The Role of Claudins Ronak Jagdeep Shah and John C. Lieske See related article on page 1542. Original Articles Chronic Kidney Disease 1463 Effect of Treatment of Metabolic Acidosis on Vascular Endothelial Function in Patients with CKD: A Pilot Randomized Cross-Over Study Jessica Kendrick, Pratik Shah, Emily Andrews, Zhiying You, Kristen Nowak, Andreas Pasch, and Michel Chonchol See related editorial on page 1451. 1471 Kidney Function Decline in Patients with CKD and Untreated Hepatitis C Infection Sara Yee Tartof, Jin-Wen Hsu, Rong Wei, Kevin B. Rubenstein, Haihong Hu, Jean Marie Arduino, Michael Horberg, Stephen F. Derose, Lei Qian, and Carla V. Rodriguez Clinical Nephrology 1479 Perfluorinated Chemicals as Emerging Environmental Threats to Kidney Health: A Scoping Review John W. Stanifer, Heather M. Stapleton, Tomokazu Souma, Ashley Wittmer, Xinlu Zhao, and L. Ebony Boulware Cystic Kidney Disease 1493 Vascular Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Kristen L. Nowak, Wei Wang, Heather Farmer-Bailey, Berenice Gitomer, Mikaela Malaczewski, Jelena Klawitter, Anna Jovanovich, and Michel Chonchol Glomerular and Tubulointerstitial Diseases 1502 Peripheral Blood B Cell Depletion after Rituximab and Complete Response in Lupus Nephritis Liliana Michelle Gomez Mendez, Matthew D. -

Syphilis Staging and Treatment Syphilis Is a Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Caused by the Treponema Pallidum Bacterium

Increasing Early Syphilis Cases in Illinois – Syphilis Staging and Treatment Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by the Treponema pallidum bacterium. Syphilis can be separated into four different stages: primary, secondary, early latent, and late latent. Ocular and neurologic involvement may occur during any stage of syphilis. During the incubation period (time from exposure to clinical onset) there are no signs or symptoms of syphilis, and the individual is not infectious. Incubation can last from 10 to 90 days with an average incubation period of 21 days. During this period, the serologic testing for syphilis will be non-reactive but known contacts to early syphilis (that have been exposed within the past 90 days) should be preventatively treated. Syphilis Stages Primary 710 (CDC DX Code) Patient is most infectious Chancre (sore) must be present. It is usually marked by the appearance of a single sore, but multiple sores are common. Chancre appears at the spot where syphilis entered the body and is usually firm, round, small, and painless. The chancre lasts three to six weeks and will heal without treatment. Without medical attention the infection progresses to the secondary stage. Secondary 720 Patient is infectious This stage typically begins with a skin rash and mucous membrane lesions. The rash may manifest as rough, red, or reddish brown spots on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and/or torso and extremities. The rash does usually does not cause itching. Rashes associated with secondary syphilis can appear as the chancre is healing or several weeks after the chancre has healed. -

ORIGINAL ARTICLE a Clinical and Histopathological Study of Lichenoid Eruption of Skin in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Dhaka

ORIGINAL ARTICLE A Clinical and Histopathological study of Lichenoid Eruption of Skin in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Dhaka. Khaled A1, Banu SG 2, Kamal M 3, Manzoor J 4, Nasir TA 5 Introduction studies from other countries. Skin diseases manifested by lichenoid eruption, With this background, this present study was is common in our country. Patients usually undertaken to know the clinical and attend the skin disease clinic in advanced stage histopathological pattern of lichenoid eruption, of disease because of improper treatment due to age and sex distribution of the diseases and to difficulties in differentiation of myriads of well assess the clinical diagnostic accuracy by established diseases which present as lichenoid histopathology. eruption. When we call a clinical eruption lichenoid, we Materials and Method usually mean it resembles lichen planus1, the A total of 134 cases were included in this study prototype of this group of disease. The term and these cases were collected from lichenoid used clinically to describe a flat Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University topped, shiny papular eruption resembling 2 (Jan 2003 to Feb 2005) and Apollo Hospitals lichen planus. Histopathologically these Dhaka (Oct 2006 to May 2008), both of these are diseases show lichenoid tissue reaction. The large tertiary care hospitals in Dhaka. Biopsy lichenoid tissue reaction is characterized by specimen from patients of all age group having epidermal basal cell damage that is intimately lichenoid eruption was included in this study. associated with massive infiltration of T cells in 3 Detailed clinical history including age, sex, upper dermis. distribution of lesions, presence of itching, The spectrum of clinical diseases related to exacerbating factors, drug history, family history lichenoid tissue reaction is wider and usually and any systemic manifestation were noted. -

Understanding Vasculitis Factsheet

Vasculitis - The Facts This factsheet is intended as a simple There is no cure for PSV, but it can usually be introduction to vasculitis for those who have just controlled by use of steroids, chemotherapy and been diagnosed with vasculitis, members of their immune suppressing drugs. Long term drug therapy is family, friends, work colleagues and for others often required. If all goes well some patients go into who may want to know about the disease. “full remission” - ie they no longer need drugs. But relapse is common. What is Vasculitis Vasculitis is a rare inflammatory disease which affects People suffering from vasculitis often experience about 2-3000 new people each year in the UK. muscle weakness and chronic fatigue. Some Vasculitis means inflammation of the blood vessels. experience chronic pain due to nerve damage or Any vessels in any part of the body can be affected. severe migraines and headaches due to damaged blood vessels in the head. There are several different types of vasculitis. In the first type, the acute form, it can be caused by Others require dialysis or kidney transplants. Many infections, reaction to drugs or exposure to chemicals. have breathing problems and others are left with Often the problem is localised, such as a rash. In these permanent physical disabilities. cases the disease usually needs no treatment. Other types of vasculitis can be secondary to (or as a The most “common” types of these rare consequence of) other illnesses such as rheumatoid vasculitis diseases are: arthritis or some types of cancer. ° Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA) (previously known as Wegener’s Granulomatosis) The third group is known as Primary Systemic ° Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA) Vasculitis (PSV). -

The Coexistence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Psoriasis: Is It Possible?

CASE REPORT The Coexistence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Psoriasis: Is It Possible? Hendra Gunawan, Awalia, Joewono Soeroso Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Airlangga University - Dr. Soetomo Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia Corresponding Author: Prof. Joewono Soeroso, MD., M.Sc, PhD. Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Airlangga University - Dr. Soetomo Hospital. Jl. Mayjen. Prof. Dr. Moestopo 4-6, Surabaya 60132, Indonesia. email: [email protected]; [email protected]. ABSTRAK Lupus eritematosus sistemik (LES) adalah penyakit autoimun kronik eksaserbatif dengan manifestasi klinis yang beragam. Psoriasis vulgaris adalah penyakit kulit yang menyerang 1-3% dari populasi. Patofisiologi mengenai tumpang tindihnya penyakit tersebut belum sepenuhnya diketahui. Hal ini menyebabkan adanya tantangan tersendiri dalam tatalaksana kedua penyakit tersebut. Dua orang laki-laki dengan LES dan psoriasis vulgaris dilaporkan dengan manifestasi klinis eritroderma berulang dengan fotosensitif. Perbaikan klinis dicapai setelah terapi kombinasi metilprednisolon dengan metotrexat. Adanya LES yang tumpang tindih psoriasis vulgaris merupakan suatu fenomena klinis yang langka. Hubungan kedua penyakit tersebut dapat berupa saling mendahului atau tumpang tindih pada suatu waktu yang sama dan memiliki hubungan dengan adanya anti- Ro/SSA. Adanya tumpang tindih dari dua penyakit tersebut memberikan paradigma baru dalam patofisiologi, diagnosis, dan tatalaksana di masa mendatang. Kata kunci: lupus eritematosus sistemik, psoriasis vulgaris, psoriatic artritis, overlap syndrome. ABSTRACT Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease with various clinical disorders and frequent exacerbations. Psoriasis vulgaris is a common skin disorder which affect 1-3% of general populations. The pathophysiology regarding the coexistence of these diseases is not fully understood. Therapeutic challenges arise since the treatment one of these diseases may aggravate the other. -

African Americans and Lupus

African Americans QUICK GUIDE and Lupus 1 Facts about lupus n People of all races and ethnic groups can develop lupus. n Women develop lupus much more often than men: nine of every 10 It is not people with lupus are women. Children can develop lupus, too. known why n Lupus is three times more common in African American women than lupus is more in Caucasian women. common n As many as 1 in 250 African American women will develop lupus. in African Americans. n Lupus is more common, occurs at a younger age, and is more severe in African Americans. Some scientists n It is not known why lupus is more common in African Americans. Some scientists think that it is related to genes, but we know that think that it hormones and environmental factors play a role in who develops is related to lupus. There is a lot of research being done in this area, so contact the genes, but LFA for the most up-to-date research information, or to volunteer for we know that some of these important research studies. hormones and environmental What is lupus? factors play 2 n Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease that can damage any part of a role in who the body (skin, joints and/or organs inside the body). Chronic means develops that the signs and symptoms tend to persist longer than six weeks lupus. and often for many years. With good medical care, most people with lupus can lead a full life. n With lupus, something goes wrong with your immune system, which is the part of the body that fights off viruses, bacteria, and germs (“foreign invaders,” like the flu). -

Comorbidities in Psoriasis: the Recognition of Psoriasis As a Systemic Disease and Current Management

Review Derleme 71 DOI: 10.4274/turkderm.09476 Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereology 2017;51:71-7 Comorbidities in psoriasis: The recognition of psoriasis as a systemic disease and current management Psoriazisde komorbiditeler: Psoriazisin sistemik hastalık olarak kabul edilmesi ve güncel yaklaşım Göknur Kalkan Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Dermatology, Ankara, Turkey Abstract Psoriasis, with a worldwide prevalence of 2-3%, is now assumed as a systemic chronic inflammatory disease accompanied by comorbidities while it was accepted as a disease limited only to the skin in the past. There are several classifications of the comorbidities which are more common in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Simply, comorbidities can be classified as classic, emerging, related to lifestyle, related to treatment. They can also be categorized as medical comorbidities, psychiatric/psychologic comorbidities, and behaviors contributing to medical and psychiatric comorbidities. In this review, providing early diagnosis and treatment of comorbidities, learning screening recommendations for early detection and long-term disease control and improvement in life quality by integrated, multidisciplinary approach were targeted. Keywords: Psoriasis, comorbidity, systemic disease Öz Tüm dünyada %2-3 oranında görülme sıklığına sahip psoriazis, geçmişte sadece deriye sınırlı kabul edilirken, günümüzde birçok komorbiditenin eşlik ettiği kronik sistemik enflamatuvar bir hastalık olarak ele alınmaktadır. Orta-şiddetli düzeyde -

A Case of Discoid Lupus Erythematosus Masquerading As Acne

Letters to the Editor 175 A Case of Discoid Lupus Erythematosus Masquerading as Acne Anastasios Stavrakoglou, Jenny Hughes and Ian Coutts Department of Dermatology, Hillingdon Hospital, Pield Heath Road, Uxbridge UB8 3NN, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted July 4, 2007. Sir, On examination he had a widespread acneiform eruption, We describe here a case of discoid lupus erythemato- which was distributed on his face, pre-sternal area and back, particularly down the length of his spine. He had multiple sus (DLE) masquerading as acne vulgaris. Cutaneous brown-red follicular papules and open comedones, especially manifestations of lupus erythematosus (LE) are usually on his back, and hypopigmented atrophic scars. There were no characteristic enough to permit straightforward diagnosis. pustules or nodulocystic lesions (Fig. 1). However, occasionally they may be variable and mimic Treatment was started with erythromycin 500 mg bid and other dermatological conditions. adapalene cream once daily to treat a presumed diagnosis of acne vulgaris. He was seen 3 months later with a deterioration Acneiform presentation is one of the most rarely re- of his clinical appearance and increased pruritus. This was ported and one of the most confusing, as it resembles a attributed by the patient to increased sun exposure. The photo- very common inflammatory skin disease and therefore aggravation, the intense pruritus and the absence of pustules can be easily missed clinically. Only 5 cases have been and nodulocystic lesions broadened our differential diagnosis reported in the literature (1–4). The patient described and therefore diagnostic biopsies were obtained. A biopsy from the back where the rash was most suggestive clinically here presented with a widespread pruritic acneiform of acne vulgaris, showed hyperkeratosis with orthokeratosis, rash, which was initially diagnosed and treated as epidermal atrophy and extensive vacuolar degeneration of the acne vulgaris with no response. -

(MRA) and Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) Medical Policy

Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) and Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) Medical Policy The content of this document is used by plans that do not utilize NIA review. Service: Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) and Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) PUM 250-0027-1712 Medical Policy Committee Approval 12/11/2020 Effective Date 01/01/2021 Prior Authorization Needed Yes Description: Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) and Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) use Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology to produce detailed 2-dimensional or 3- dimensional images of the vascular system and may be tailored to assess arteries or veins. It is often used for vascular conditions where other types of imaging are considered inferior or contraindicated, and to decrease risk of cumulative radiation exposure and often instead of invasive procedures. Indications of Coverage: A. MRA/MRV is considered medically necessary for the anatomical regions listed below when the specific indications or symptoms described are documented: 1. Head/Brain: a. Suspected intracranial aneurysm (ICA) or arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Any of the following: 1. Acute severe headache, severe exertional headache, or sudden onset of explosive headache, in individuals with signs / symptoms highly suggestive of a leaking/ruptured internal carotid artery or arteriovenous malformation. 2. Known subarachnoid hemorrhage or diagnosis of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage with concern for underlying vascular abnormality. 3. Suspected arteriovenous malformation (AVM) or dural AV fistula in an individual with prior indeterminate imaging study 4. Thunderclap headache with question of underlying vascular abnormality AND prior negative workup to include EITHER i. negative brain MRI, OR ii. Negative brain CT and negative lumbar puncture Page 1 of 15 5. -

Successful Treatment with Rituximab in a Patient with TTP Secondary to Severe ANCA-Associated Vasculitis

□ CASE REPORT □ Successful Treatment with Rituximab in a Patient with TTP Secondary to Severe ANCA-Associated Vasculitis Yukari Asamiya 1, Takahito Moriyama 1, Mari Takano 1, Chihiro Iwasaki 1, Kazuo Kimura 1, Yukako Ando 1, Akiko Aoki 1, Kan Kikuchi 2, Takashi Takei 1, Keiko Uchida 1 and Kosaku Nitta 1 Abstract We report a case of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) secondary to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis treated by rituximab. TTP secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis is very rare and has a high mortality rate. We employed rituximab and successfully treated TTP secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis, because standard therapies, such as steroid therapy, intravenous pulse cyclophos- phamide, and repeated plasma exchange (PE), did not suppress her disease activity. This is the first report to suggest that rituximab can achieve complete remission of TTP secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis. Key words: ANCA-associated vasculitis, TTP, rituximab, renal failure, intrapulmonary hemorrhage, hemo- dialysis (Inter Med 49: 1587-1591, 2010) (DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3135) pies such as steroids and therapeutic PE (4-6). However, ri- Introduction tuximab was employed mainly against idiopathic TTP, and there were few reports discussing treatment of secondary Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated TTP; in particular, TTP with ANCA-associated vasculitis vasculitis is recognized as a multisystem autoimmune dis- was rare. Here, we report a patient with TTP secondary to ease characterized by ANCA production and small vessel in- myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (MPO- flammation (1). It’s typical clinical manifestations are rap- ANCA) associated vasculitis who was treated using rituxi- idly progressive glomerulonephritis and the occasional de- mab combined with steroid pulse, IVCY and repeated PE.