Ingmar Bergman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rape and the Virgin Spring Abstract

Silence and Fury: Rape and The Virgin Spring Alexandra Heller-Nicholas Abstract This article is a reconsideration of The Virgin Spring that focuses upon the rape at the centre of the film’s action, despite the film’s surface attempts to marginalise all but its narrative functionality. While the deployment of this rape supports critical observations that rape on-screen commonly underscores the seriousness of broader thematic concerns, it is argued that the visceral impact of this brutal scene actively undermines its narrative intent. No matter how central the journey of the vengeful father’s mission from vengeance to redemption is to the story, this ultimately pales next to the shocking impact of the rape and murder of the girl herself. James R. Alexander identifies Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring as “the basic template” for the contemporary rape-revenge film[1 ], and despite spawning a vast range of imitations[2 ], the film stands as a major entry in the canon of European art cinema. Yet while the sumptuous black and white cinematography of long-time Bergman collaborator Sven Nykvist combined with lead actor Max von Sydow’s trademark icy sobriety to garner it the Academy Award for Best Foreign film in 1960, even fifty years later the film’s representation of the rape and murder of a young girl remain shocking. The film evokes a range of issues that have been critically debated: What is its placement in a more general auteurist treatment of Bergman? What is its influence on later rape-revenge films? How does it fit into a broader understanding of Swedish national cinema, or European art film in general? But while the film hinges around the rape and murder, that act more often than not is of critical interest only in how it functions in these more dominant debates. -

Innovators: Filmmakers

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: FILMMAKERS David W. Galenson Working Paper 15930 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15930 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Filmmakers David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15930 April 2010 JEL No. Z11 ABSTRACT John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were experimental filmmakers: both believed images were more important to movies than words, and considered movies a form of entertainment. Their styles developed gradually over long careers, and both made the films that are generally considered their greatest during their late 50s and 60s. In contrast, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard were conceptual filmmakers: both believed words were more important to their films than images, and both wanted to use film to educate their audiences. Their greatest innovations came in their first films, as Welles made the revolutionary Citizen Kane when he was 26, and Godard made the equally revolutionary Breathless when he was 30. Film thus provides yet another example of an art in which the most important practitioners have had radically different goals and methods, and have followed sharply contrasting life cycles of creativity. -

The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521380650 - The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More information The Films of Ingmar Bergman This volume provides a concise overview of the career of one of the modern masters of world cinema. Jesse Kalin defines Bergman’s conception of the human condition as a struggle to find meaning in life as it is played out. For Bergman, meaning is achieved independently of any moral absolute and is the result of a process of self-examination. Six existential themes are explored repeatedly in Bergman’s films: judgment, abandonment, suffering, shame, a visionary picture, and above all, turning toward or away from others. Kalin examines how Bergman develops these themes cinematically, through close analysis of eight films: well-known favorites such as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal, Smiles of a Summer Night, and Fanny and Alexander; and im- portant but lesser-known works, such as Naked Night, Shame, Cries and Whispers, and Scenes from a Marriage. Jesse Kalin is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Humanities and Professor of Philosophy at Vassar College, where he has taught since 1971. He served as the Associate Editor of the journal Philosophy and Literature, and has con- tributed to journals such as Ethics, American Philosophical Quarterly, and Philosophical Studies. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521380650 - The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE FILM CLASSICS General Editor: Ray Carney, Boston University The Cambridge Film Classics series provides a forum for revisionist studies of the classic works of the cinematic canon from the perspective of the “new auterism,” which recognizes that films emerge from a complex interaction of bureaucratic, technological, intellectual, cultural, and personal forces. -

25 Years of Media Investing in Creativity, Building the Future 1 - 2 December 2016, Bozar, Brussels

25 YEARS OF MEDIA INVESTING IN CREATIVITY, BUILDING THE FUTURE 1 - 2 DECEMBER 2016, BOZAR, BRUSSELS #MEDIA25 “Oh how Shakespeare would have loved cinema!” Derek Jarman, filmmaker and writer “‘Culture’ as a whole, and in the widest sense, is the glue that forms identity and that determines the soul of Europe. And cinema has a privileged position in that realm… Movies helped to invent and to perpetuate the ‘American Dream’. They can do wonders for the image of Europe, too.” Wim Wenders, filmmaker “The best advice I can offer to those heading into the world of film is not to wait for the system to finance your projects and for others to decide your fate.” Werner Herzog, filmmaker “You don’t make a movie, the movie makes you.” Jean-Luc Godard, filmmaker “A good film is when the price of the dinner, the theatre admission and the babysitter were worth it.” Alfred Hitchcock, filmmaker The 25th anniversary of MEDIA The European Commission, in collaboration with the Centre for Fine Arts (BOZAR), is organising a special European Film Forum (EFF) to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the MEDIA programme, which supports European audiovisual creations and their distribution across borders. Over these 25 years, MEDIA has been instrumental in supporting the audiovisual industry and promoting collaboration across borders, as well as promoting our shared identity and values within and outside Europe. This special edition of the European Film Forum is the highlight of the 25th anniversary celebrations. On the one hand, it represents the consummation of the testimonials collected from audiovisual professionals from across Europe over the year. -

Camera Stylo 2021 Web

Cries and Whispers and Prayers MENA FOUDA Mena Fouda is an aspiring storyteller. Her dignifed process includes: petting and interviewing every cat she is lucky to cross paths with, telling bedtime stories to her basil plants, smelling expensive perfume to fnd out its secrets, and dancing to dreamy music in languages she can half-understand. 61 6 Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (1972) starts with neither cries nor whispers but a natural silence. When we are first brought into this world, we see a statue, a thing that by its very nature is made to be unmoving: a figure that crystalizes movement. It is a quiet dawn and light streams softly past the trees, suggesting a tranquil openness to this environment. At first glance, I wonder what it would be like to walk these serene fields, to dance beneath these emerging rays of light. This must be somebody’s paradise. Without warning, this utopic space bleeds a deep red, until the colour overtakes the screen and transports us somewhere inside the manor. Here, we see more statues and a number of clocks before cutting to a larger view of the internal landscape. A sense of claustrophobia wraps its vicious hands around my throat. Something dead twists in my stomach. I no longer want to walk through here. I want to leave this damned Hell. Writing about this film is difcult—not because it doesn’t stir passion within me, but because it stirs too much. Having started with this film, I have since gone on to enjoy Bergman’s other works including Persona (1966), Autumn Sonata (1978), and Wild Strawberries (1957)—but I always find myself retreating to Cries and Whispers for comparison. -

Biografi Ingmar Bergman

HUVUDREDAktöRER PAUL DUNCN BENGT WA NSELIUS TExtER AV BIRGITTA SEENE, PETER COWIE, BENGT FORSLUND, ERLAND JosEPHSON OCH INGMAR BERGMAN PRODUCERAD AV REGI BENEDIkt TASCHEN BERGMAN BOKFÖRLAGET MAX STRÖM TE INGMAR BERGMAN ARCHIVES Part 1 Ingmar Bergman’s silent home movies 18 mins Part 2 Behind the scenes of Autumn Sonata 20 mins Part 3 An Image Maker; Behind the scenes documentary 32 mins Part 4 A video diary from Saraband 44 mins © 2008 TASCHEN GmbH All rights reserved. Taschen DVD 1. Ingmar Bergmans egna smalfilmer 18 min Gycklarnas afton, 1953 Det sjunde inseglet, 1957 Såsom i en spegel, 1961 Kommentarer av Marie Nyreröd 2. Från inspelningen av Höstsonaten 20 min av Arne Carlsson 3. En bildmakare; från inspelningen av Bildmakarna 32 min av Bengt Wanselius 4. En videodagbok från Saraband 44 min av Torbjörn Ehrnvall Filmremsan är från Fanny och Alexander och klippt från en 35 mm filmkopia som har visats i Ingmar Bergmans egen projektor. 00_bergman_080607.indd 1 08-06-19 14.12.51 00_bergman_080607.indd 2 08-06-19 14.12.51 4 — Innehåll Innehåll Kapitel 1 Kapitel 2 Kapitel 3 Kapitel 4 spelöppning 6 10 118 192 270 Bergmans närmaste vän och medarbetare Bergmans barndom och lärotid inom teater Trots turbulenta år med flera äktenskap, Andra hälften av femtiotalet representerar Bergmans religiösa tvivel resulterar i den Erland Josephson skriver om deras livslånga och film. Efter debuten 1938 som regissör barn, skilsmässor och förhållanden medför Bergmans första storhetstid som filmskapare berömda ”trilogin” med dess utforskande av vänskap och om sitt sista möte med Bergman i Mäster Olofsgårdens teatersektion upp- perioden ett genombrott för Bergman inom och teaterregissör. -

Music As Spiritual Metaphor in the Cinema of Ingmar Bergman

Music as Spiritual Metaphor in the Cinema of Ingmar Bergman By Michael Bird Spring 1996 Issue of KINEMA SECRET ARITHMETIC OF THE SOUL: MUSIC AS SPIRITUAL METAPHOR IN THE CINEMA OF INGMAR BERGMAN Prelude: General Reflections on Music and the Sacred: It frequently happens that in listening to a piece of music we at first do not hear the deep, fundamental tone, the sure stride of the melody, on which everything else is built... It is only after we have accustomed our ear that we find law and order, and as with one magical stroke, a single unified world emerges from the confused welter of sounds. And when this happens, we suddenly realize with delight and amazement that the fundamental tone was also resounding before, that all along the melody had been giving order and unity... - Rudolf Bultmann(1) I said to myself, it is as if the eternal harmony were conversing within itself, as it may have done in the bosom of God just before the Creation of the world. So likewise did it move in my inmost soul. - Goethe(2) One Sunday in December, I was listening to Bach’s Christmas Oratorio in Hedvig Eleonora Church... The chorale moved confidentially through the darkening church: Bach’s piety heals the torment of our faithlessness... - Ingmar Bergman(3) Ingmar Bergman has frequently indicated the immense significance of musical experience for his own personal and artistic development, just as he has also suggested that human existence at large has need for music. His words suggest that of all arts, music may be the most spiritually meaningful of all. -

CRIES & WHISPERS Background in His Book Images: My Life in Film (1990), Ingmar Bergman Has Written: “All My Films Can Be T

CRIES & WHISPERS background In his book Images: My Life in Film (1990), Ingmar Bergman has written: “All my films can be thought of in terms of black and white, except for Cries and Whispers. In the screenplay, it says that red represents for me the interior of the soul. When I was a child, I imagined the soul to be a dragon, a shadow floating in the air like blue smoke -- a huge winged creature, half bird, half fish. But inside the dragon, everything was red.” C ries & Whispers (V iskningar och rop, 1972) Colour. Running time: 91 minutes Cinematographer Sven Nykvist won an Academy Award for his work on the film. The film was also nominated for Oscars for best picture, best director, best screenplay, and best costuming. Bergman won the Technical Grand Prize for the film at the Cannes Film Festival. Plot The film is a trancelike, non-linear narrative made up of vignettes, dreams, and flashbacks. In 1880s or 1890s Sweden, “cancer-stricken, dying Agnes (37) is visited in her isolated rural mansion by her sisters Karin and Maria. As Agnes's condition deteriorates, fear and revulsion grip the sisters, who seem incapable of empathy, and Agnes's only comfort comes from her maid Anna. As the end draws closer, long repressed feelings of resentment and mistrust cause jealousy, selfishness, and bitterness to surface.” (IMDB review) “An extraordinary vision of the interior of the soul.” (Peter Cowie) Commentary ** You can read here < http://www.bergmanorama.com/films/cries_and_whispers_script.htm > how Bergman conceived of the four women. “Cries and Whispers envelops us in a tomb of dread, pain and hate, and to counter these powerful feelings it summons selfless love. -

Major Swedish Retrospective of Classic Early Films

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Museum of Modern Art 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart MAJOR SWEDISH RETROSPECTIVE OF CLASSIC EARLY FILMS See enclosed screening schedule .Two giants of the Swedish cinema, Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller, will be honored in a major historical retrospective to be introduced by the Department of Film of The Museum of Modern Art from February 3 through April 8, 1977. The new film exhibition, "Sjostrom, Stiller and Contemporaries," will present all the extant early works of these two master directors, with the exception of one unavailable print, "The Story of Gosta Berling." This will be the first time that these great silent Swedish films will be seen in the U.S. as a collection. Many other virtually unknown films dating from 1911 through 1929, which is called "The Golden Age of Swedish Cinema," will also be shown. The program is a unique opportunity to re-examine an important chapter in film history. Many of the films of Sj*ostrb*m and Stiller seem to have left a deep, strong impression even when they were first released, especially in America, Germany and Russia, according to Adrienne Mancia. The Museum Curator initiated this comprehensive retrospective, with the cooperation of Anna-Lena Wibom and her staff at the Swedish Film Institute, which is dedicated to the preservation of early Swedish film classics. Both Harry Schein, Chairman of the Board of the Institute, and Ms. Wibom, Director of the Institute's Cinemateque, will come to New York from Stockholm for the inauguration of this event. -

Downloaden Download

Ivo Holmqvist INGMAR BERGMAN'S WINTER JOURNEY — intertextuality in `Larmar och gör sig till' Ingmar Bergman maintains on the back cover of his Femte akten (The Fifth Act, Norstedts 1994) that the four plays contained in that volume are written without any particular performance medium in thought, like Bach's cembalo sonatas ... They can be played by a string quartet, a woodwind ensemble, by guitar, organ or piano. I have written in the manner that I am used to for more than fifty years - it looks like theatre but could equally well be film, television or just a text for reading.1 However, these plays did not remain unperformed reading dramas, as three of them have been adapted for television, and the fourth for the stage. `Efter repetitionen' (After the Rehersal) was filmed long before publication, and `Sista skriket' (The Last Cry) was originally performed on stage but then converted for television. Film and theatre merge in that play, illustrating Ingmar Bergman's much-quoted words about theatre as a wife and film as a mistress. During his long creative life (he turned eighty on July 14, 1998, and is still going strong), he has demonstrated how well the two media combine. In `Sista skriket' he uncovers early Swedish film history, in a reconstruction of a plausible interchange between two pioneers of the silent screen, Charles Magnusson and Georg af Klercker. The last piece in Femte akten, called `Larmar och gör sig till' (Struts and Frets), is also centred on theatre and film. In his cover text from 1Femte akten, p. -

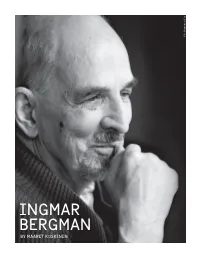

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918. -

Ingmar Bergman's Persona As a Modernist Example of Media

Filozofski vestnik | Volume XXXV | Number 2 | 2014 | 219–237 Ernest Ženko* Ingmar Bergman’s Persona as a Modernist Example of Media Determinism Introduction The film medium developed during a time of the rapid expansion of modernism, which took over almost all of art. Nevertheless, mainstream narrative cinema joined this movement only after a considerable delay. During the 1920s certain movements in cinema appropriated the main ideas of modernism, but it was only after the Second World War, in fact during the 1960s, that modernism in cinema came to full bloom. Due to its reflexive nature, the role of its auteur, and its open-endedness, Ing- mar Bergman’s film Persona (1966) is considered one of the finest examples of modernism in cinema. Persona is, nevertheless, also an exceptional example of media and technological determinism. In this film, Bergman accomplishes a reversal of a crucial modernist problem related to technology: he does not show how to animate an apparatus, but rather how media technology have infiltrated the prevailing frame of mind so deeply that the psyche can at best be grasped through the film medium itself. We should, for clarity, distinguish between a “vulgar” understanding of me- dia determinism as a reductionist, causal relation between the appearance of technological media and their impact on society, culture, art, and subjectiv- 219 ity, on the one hand, and its “soft” (or dialectical) version, on the other. In the latter, there is more space for various, sometimes even mutually opposed processes that obscure the main orientation, which nevertheless remains pre- sent in both crucial mantras of the so-called “media turn”—Marshall McLu- han’s “medium is the message”1 and Friedrich Kittler’s “media determine our 1 Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994, 7.