Faced Whistling Duck by Ilya A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black-Bellied Whistling-Duck Yellow-Billed Cuckoo Fulvous

Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Yellow-billed Cuckoo Willet* Band-rumped Storm-Petrel Northern Flicker Bewick's Wren Fulvous Whistling-Duck Black-billed Cuckoo Greater Yellowlegs Wood Stork Pileated Woodpecker Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Snow Goose* Common Nighthawk Wilson's Phalarope Magnificent Frigatebird American Kestrel Golden-crowned Kinglet Ross's Goose Chuck-will's-widow Red-necked Phalarope Northern Gannet Merlin* Ruby-crowned Kinglet Greater White-fronted Goose Eastern Whip-poor-will Red Phalarope Anhinga Peregrine Falcon Eastern Bluebird Brant Chimney Swift Great Skua Great Cormorant Monk Parakeet Veery Cackling Goose Ruby-throated Hummingbird Pomarine Jaeger Double-crested Cormorant Ash-throated Flycatcher Gray-cheeked Thrush Canada Goose Rufous Hummingbird Parasitic Jaeger American White Pelican Great Crested Flycatcher Bicknell's Thrush Mute Swan Clapper Rail Long-tailed Jaeger Brown Pelican Western Kingbird Swainson's Thrush Trumpeter Swan King Rail Dovekie American Bittern Eastern Kingbird Hermit Thrush Tundra Swan Virginia Rail Thick-billed Murre Least Bittern Gray Kingbird Wood Thrush Wood Duck Sora Razorbill Great Blue Heron* Scissor-tailed Flycatcher American Robin Atlantic Puffin Great Egret Blue-winged Teal Common Gallinule Fork-tailed Flycatcher Varied Thrush Black-legged Kittiwake Snowy Egret Northern Shoveler American Coot Olive-sided Flycatcher Gray Catbird Sabine's Gull Little Blue Heron Gadwall Purple Gallinule Eastern Wood-Pewee Brown Thrasher Bonaparte's Gull Tricolored Heron Eurasian Wigeon Yellow Rail Yellow-bellied -

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

ILSOLC Bird Checklist

Birding in Seguin Irma Lewis Seguin Outdoor Irma Lewis Seguin, Texas is located in south- central Texas, in an ecological area on Learning Center Seguin Outdoor Learning the boundary of Blackland Prairie to the north and the Post Oak Savannah The Seguin Outdoor Learning Center to the south and east. Most of the Center a 115-acre private, non surrounding land is in agricultural use, primarily cattle grazing, providing a -profit educational facility fairly diverse environment for birds. nestled along Geronimo Creek The Guadalupe River runs through the in northeast Seguin. Our city. Large pecan and cypress trees line the river, including the city park, facilities include a pavilion, Starcke Park, on Bus. 123 South. The natural history center, walking trail in Starcke Park East, along the confluence of Walnut Branch, environmental science center, offers good birding for warblers, blue- amphitheater, ropes course, “Education Through Experience For All Ages” birds and other passerines. Several small reservoirs located along the river nature trail, outdoor class- near town, including Lakes Dunlap, room and pond. Schools, youth McQueeney, and Placid also provide groups, sports teams, clubs, areas for waterfowl. churches and corporations enjoy our peaceful, natural Some species that are common around setting where children and Seguin may be of special interest to citizens of the community can birders from other regions. learn through discovery and Scissor-tailed Flycatchers are unique adventure common during the breeding season. Look for them on fences and telephone experiences. wires anywhere in the countryside around Seguin. Crested Caracaras are The ILSOLC is open to also common in the countryside and are Birding Hours: members, scheduled and especially visible when feeding on Monday-Friday, 8a-5p road-kill carcasses, often in the supervised groups only. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Here Today...Gone Tomorrow

Sponsored by Blue Lagoon Island & Marine Vendors from Nassau Dolphin Encounters-Project BEACH Contest Deadline: April 8th, 2011 Endangered Wildlife in the Bahamas What do the Dodo bird, Stellar’s sea cow, As late as 1707, sailors, whalers, and Passenger Pigeon, and the Bajii River Dolphin fishermen could kill as many as a have in common? Well they are all now extinct, hundred of these non-aggressive seals gone forever from our planet! When you think of an in one night and use them for valuable endangered or extinct animal, dinosaurs and giant food and oil. The last confirmed sighting of this once abundant mastodons may come to mind but, believe it or not, marine mammal was in 1952, but they are now classified as many animals are at risk of extinction right here in our extinct , with not even one seal of this species is alive today. Bahamaland. Let’s take a look at three animals—the Bahama Parrot, the Imagine going to the beach and having a colony of seals a few West Inidan Whistling Duck, & the Bahama Boa — that are hundred yards from you sunbathing. In the Bahamas? Yes! When endangered today but still have a chance of being protected Columbus came to The Bahamas, he noted in his journal seeing and surviving in the wild in The Bahamas. “sea wolves” which were actually passive Caribbean Monk Seals. The Bahama Parrot When Columbus visited our The Bahama Parrot eats The choices in nesting has put shores he also saw another a variety of fruits both populations at risk to unique animal: the ranging from wild guava, predators like cats and Bahama Parrot . -

2.9 Waterbirds: Identification, Rehabilitation and Management

Chapter 2.9 — Freshwater birds: identification, rehabilitation and management• 193 2.9 Waterbirds: identification, rehabilitation and management Phil Straw Avifauna Research & Services Australia Abstract All waterbirds and other bird species associated with wetlands, are described including how habitats are used at ephemeral and permanent wetlands in the south east of Australia. Wetland habitat has declined substantially since European settlement. Although no waterbird species have gone extinct as a result some are now listed as endangered. Reedbeds are taken as an example of how wetlands can be managed. Chapter 2.9 — Freshwater birds: identification, rehabilitation and management• 194 Introduction such as farm dams and ponds. In contrast, the Great-crested Grebe is usually associated with large Australia has a unique suite of waterbirds, lakes and deep reservoirs. many of which are endemic to this, the driest inhabited continent on earth, or to the Australasian The legs of grebes are set far back on the body region with Australia being the main stronghold making them very efficient swimmers. They forage for the species. Despite extensive losses of almost completely underwater pursuing fish and wetlands across the continent since European aquatic arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. settlement no extinctions of waterbirds have They are strong fliers but are poor at manoeuvering been recorded from the Australian mainland as in flight and generally prefer to dive underwater a consequence. However, there have been some to escape avian predators or when disturbed by dramatic declines in many populations and several humans. Flights between wetlands, some times species are now listed as threatened including over great distances, are carried out under the cover the Australasian Bittern, Botaurus poiciloptilus of darkness when it is safe from attack by most (nationally endangered). -

A Partial Classification of Waterfowl (Anatidae) Based on Single-Copy Dna

A PARTIAL CLASSIFICATION OF WATERFOWL (ANATIDAE) BASED ON SINGLE-COPY DNA CORT S. MADSEN, KEVIN P. MCHUGH, AND SIWO R. DE KLOET Instituteof MolecularBiophysics, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida 32306 USA ABSTR^CT.--Single-copyDNA-DNA hybridizationwas used to establishphylogenetic re- lationshipsamong 13 speciesof waterfowl (Anatidae) chosenfrom 10 tribes. On the basisof UPGMA clusteringof ATtodistances, we suggestthat the tribes Anatini, Aythyini, Tadornini, Mergini, and Cairinini diverged more recently than the Anserini, Stictonettini,Oxyurini, Dendrocygnini,and Anseranatini.The FreckledDuck (Stictonettanaevosa, tribe Stictonettini) is only distantlyrelated to the other Anatidae.Presumably the lineage divergedvery early. The sheldgeese(tribe Tadornini) and the true geese(Anserini) are only remotely related. The Oxyurini, consideredto be in the subfamilyAnatinae, is remotely related to the other Anatidae. The Dendrocygnini form an isolatedtribe with no closerelationship to the swans and geese(subfamily Anserinae). We found that the screamers(Anhimidae) are distantly related to the Anatidae. A method to estimate missing cells in a data matrix of pairwise distancesis presented. ReceivedI May 1987,accepted 16 February1988. RECENTLY,nucleic acid sequenceanalysis has up about 10-40% of the total DNA (Eden et al. been usedto estimaterelationships of many or- 1978) but containsonly a small percentageof ganisms. The analysis can include direct se- the total sequencediversity. The remaining60- quencing of individual cloned genes -

Waterfowl of North America: WHISTLING DUCKS Tribe Dendrocygnini

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010) Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Waterfowl of North America: WHISTLING DUCKS Tribe Dendrocygnini Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciwaterfowlna Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Waterfowl of North America: WHISTLING DUCKS Tribe Dendrocygnini" (2010). Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010). 8. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciwaterfowlna/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WHISTLING DUCKS Tribe Dendrocygnini Whistling ducks comprise a group of nine species that are primarily of tropical and subtropical distribution. In common with the swans and true geese (which with them comprise the subfamily Anserinae), the included spe cies have a reticulated tarsal surface pattern, lack sexual dimorphism in plum age, produce vocalizations that are similar or identical in both sexes, form relatively permanent pair bonds, and lack complex pair-forming behavior pat terns. Unlike the geese and swans, whistling ducks have clear, often melodious whistling voices that are the basis for their group name. The alternative name, tree ducks, is far less appropriate, since few of the species regularly perch or nest in trees. All the species have relatively long legs and large feet that extend beyond the fairly short tail when the birds are in flight. -

Duck, Fulvous Whistling

Waterfowl — Family Anatidae 47 Waterfowl — Family Anatidae Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor A population collapse that eliminated the Fulvous Whistling Duck from San Diego County in the 1950s was on the verge of eliminating it from all of California by the beginning of the 21st century. The species is kept commonly in captivity—or as an ornamental waterfowl in free flight—so for decades sightings have been assumed to be due to escapees. Since 1997 even that source has largely dried up. Breeding distribution: The status of the Fulvous Whistling-Duck in San Diego County was poorly docu- Photo by Anthony Mercieca mented before the species was extirpated. The only spe- cific record of breeding is J. B. Dixon’s of small young in mouth (V10) 26 June 2003 (R. T. Patton, J. R. Barth) and the San Luis Rey River valley on 18 May 1931 (Willett three in the nearby estuary 2 August 2003 (M. Billings). 1933). Winter: One specimen was collected 5 miles west of Migration: Stephens (1919a) wrote of the Fulvous Santee (P11) 14 December 1954 (SDNHM 30023), anoth- Whistling-Duck, “Rather common spring migrant. Rare er at San Diego in December, year not cited (Salvadori winter visitant. Stragglers may remain through summer 1895). and breed.” Yet two of the three SDNHM specimens were collected in fall: Mission Bay (Q8), 10 September 1922 Conservation: The reasons for the Fulvous Whistling- (11313), and Warner Springs (F19), 21 October 1956 Duck’s extirpation remain unclear. The species is not (30051). The last represents the most recent presumed dependent on natural habitats; in the southeastern U.S. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Bird Checklist

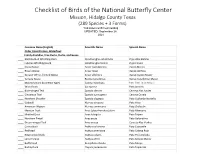

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

Welfare Assessment for Captive Anseriformes: a Guide for Practitioners and Animal Keepers

animals Article Welfare Assessment for Captive Anseriformes: A Guide for Practitioners and Animal Keepers Paul Rose 1,2,* and Michelle O’Brien 2 1 Centre for Research in Animal Behaviour, Psychology, Washington Singer, University of Exeter, Perry Road, Exeter EX4 4QG, UK 2 Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge Wetland Centre, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire GL2 7BT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 May 2020; Accepted: 1 July 2020; Published: 3 July 2020 Simple Summary: Zoological collections are constantly working to find new ways of improving their standards of care for the animals they keep. Many species kept in zoos are also found in private animal collections. The knowledge gained from studying these zoo-housed populations can also benefit private animal keepers and their animals. Waterfowl (ducks, geese, and swans) are examples of species commonly kept in zoos, and in private establishments, that have received little attention when it comes to understanding their core needs in captivity. Measuring welfare (how the animal is coping with the environment that it is in) is one way of understanding whether a bird’s needs are being met by the care provided to it. This paper provides a method for measuring the welfare of waterfowl that can be applied to zoo-housed birds as well as to those in private facilities. The output of such a welfare measurement method can be used to show where animal care is good (and should be continued at a high standard) and to identify areas where animal care is not meeting the bird’s needs and hence should be altered or enhanced to be more suitable for the birds being kept.