Major Bleeding Events in Jordanian Patients Undergoing Percutaneous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

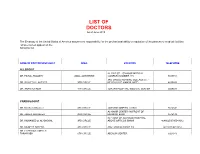

LIST of DOCTORS As of June 2018

LIST OF DOCTORS As of June 2018 The Embassy of the United States of America assumes no responsibility for the professional ability or reputation of the persons or medical facilities whose names appear on the following list. NAME OF DOCTOR/SPECIALIST AREA LOCATION TELEPHONE ALLERGIST AL-RAZI ST. - SAMOOR MEDICAL DR. FAISAL TBAILEH JABAL ALHUSSEIN COMPLEX NUMBER 145 5695151 3RD CIRCLE NURSING COLLAGE ST. - DR. SAYYED AL-NATHER 3RD CIRCLE NEAR HAYAT AMMAN HOTEL 4655893 DR. ANAN ALFAQIH 4TH CIRCLE JORDAN HOSPITAL/ MEDICAL CENTER 5609031 CARDIOLOGIST DR. Munther AlSaafeen 4TH CIRCLE JORDAN HOSPITAL CLINIC 5624840 AL-KHAIR CENTER- IN FRONT OF DR. ZAHER ALKASEEH 3RD CIRCLE HOUSING BANK 4645138 IN FRONT OF ALKHALDI HOSPITAL, DR. MOHAMED O. AL-BAGGAL 3RD CIRCLE ABOVE OPTICOS SHAMI 4646625/0795543012 DR. MUNEER AREEDA 4TH CIRCLE ABU HASSAN COMPLEX 4613613/4613614 DR. HATEM SALAMEH AL- TARAWNEH 5TH CIRCLE ABDOUN CENTER 5924343 DR. AHMAD MOHANNA AL ABDOUN CENTER, INFRONT OF ARABIC HARASEES 5TH CIRCLE CENTER 5924343 DR. IMAD HADAD 4TH CIRCLE JORDAN HOSPITAL CLINIC 5626197/0795303502 DR. NAZIH NAJEH AL-QADIRI 4TH CIRCLE JORDAN HOSPITAL CLINIC 5680060/0796999695 JABER IBN HAYYAN ST./ IBN HAYYAN DR. SUHEIL HAMMOUDEH SHMEISANI MEDICAL COMPLEX 5687484/0795534966 DR. YOUSEF QOUSOUS JABAL AMMAN AL-KHALIDI ST./ AL- BAYROUNI COMP. 4650888/0795599388 CARDIOVASCULAR SURGEON JABAL AMMAN NEAR ALKHALDI DR. SUHEIL SALEH 3RD CIRCLE HOSPITAL 4655772 / 079-5533855 COLORECTAL & GENERAL SURGERY DR. WAIL FATAYER KHALIDI HOSPITAL RAJA CENTER 5TH FLOOR 4633398 / 079-5525090 AL- RYAD COMP.BLDG NO. 41/ FLOOR DR. MARWAN S. RUSAN KHALIDI HOSPITAL ST. GROUND 4655772 / 0795530049 DR. JAMAL ARDAH TLA' AL- ALI IBN AL-HAYTHAM HOSPITAL 5602780 / 5811911 DENTISTS DENTAL CONSULTATION CENTER MAKA ST. -

All Participants

AHF Member list Hospital name Country Abo Kair Hospital Egypt Abou Jaoude Hospital Lebanon Ahmad Maher Teaching Hospital Egypt Ain Shams University Hospitals Egypt Ain Wa Zein Hospital Lebanon Ajman Medical Area UAE Al Adwani General Hospital Saudi Arabia Al Ahli Specialized Hospital Syria Al Ahli Typical Hospital Yemen Al Ahly Hospital Egypt Al Ainy Hospital Syria Al Amal Hospital Saudi Arabia Al Amal Hospital Egypt Al Amin Specialized Hospital Syria Al Anssar Hospital Saudi Arabia Al Asafra Hospital Egypt Al Assad University Hospital Syria Al Baraem Hospital Syria Al Bassel Heart Institute Syria Al Bassel Hospital- Hama Syria Al Ber Hospital and Social Services Syria Al Borg Laboratories Saudi Arabia Al Diaa Hospital Syria Al Dorra Center for Physiotherapy Egypt Al Fateh Hospital Syria Al Gesry Hospital Syria Al Ghazali Hospital Syria Al Goumhouri Teaching Hospital Yemen Al Gumhouri Hospital Yemen Al Gumhouriya Teaching Hospital Yemen Al Hamaideh Hospital Jordan Al Hamra Hospital Saudi Arabia Al Hayat General Hospital Jordan Al Hayat Hospital Lebanon Al Hekma Hospital - Tartous Syria Al Hosn Hospital Syria Al Hourani Hospital Syria Al Huda Hospital Syria Al Imam AbdelRahman Bin Faisal Hospital Saudi Arabia Al Iman Hospital Lebanon Al Inaya Al Khassa Hospital Syria Al Istiklal Hospital - Al Bilad Medical services Co Jordan Al Janoub Hospital Lebanon Hospital name Country Al Janoub- Shuayb Hospital Lebanon Al Jawhara Center for Molecular Medicine Bahrain Al Kamal Hospital- Jdeidet Artouz Syria Al Karak Hospital Jordan Al Karameh Hospital -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Ahmad Alsayed PhD, MSc, PharmD Personal Information • Name: Ahmad Riyad Fawzi Alsayed • Marital state: Married • Date of Birth: July 21th, 1987 • Phone number: 00962786770778 • Email: [email protected], [email protected] Education • PhD in Clinical Pharmacy / Therapeutics and Precision Medicine, School of Pharmacy, Queen's University Belfast, the United Kingdom, May 2018. • PhD Thesis Subject: Clinical Pharmacy, Therapeutics, Infectious Diseases, Respiratory Diseases, Human Microbiome, Biotechnology, Bioinformatics. • PhD Thesis Title: “Understanding the Lung Microbiome in Chronic Pulmonary Diseases and its Clinical Influence on Disease Outcome”. • MSc. in Pharmacology, School of Medicine, the University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan. June 2014. Thesis entitled as: “The prevalence of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in three hospitals in Amman, Jordan”. • Master level in Bioinformatics, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory - European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), Welcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, the United Kingdom. January 2018. Title: “Bioinformatics for Discovery”. • BSc. Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD), School of Pharmacy, the University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan. June 2011. • High School, Al-Omariya School, Amman, Jordan. 2005. Current Positions • Assistant Professor of Clinical Pharmacy (Therapeutics and Precision Medicine) in the Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics at Faculty of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University in Amman, Jordan. Since September 2018 – until now. • Member in Accreditation, Quality Assurance and Evaluation Committee at Faculty of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University in Amman, Jordan. Since September 2018 – until now. • Head of Alumni Follow-up Committee at Faculty of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University in Amman, Jordan. October 2019 – September 2020. -

Private Sector Project for Women's Health

Private Sector Project for Women’s Health Survey and Assessment of Private Sector Mammogram Facilities in Central and North Jordan Submitted to: Dr. Basma Khraisat Cognizant Technical Officer USAID/Jordan Submitted by: Dr. Rita Leavell Chief of Party Private Sector Project for Women’s Health Abt Associates Inc. Prepared By: May Abuhamdia BSc; eMBA/MPH September 2007 The information contained in this document is considered CONFIDENTIAL and is intended for the recipient and their authorized representatives only. Any unauthorized distribution is strictly prohibited without the prior written consent of submitter. 1 Table of Contents List of Figures 3 List of Tables 4 Acronyms 6 Introduction 7 Objectives 7 Methodology 8 Results 11 General Facility and Staffing Characteristics and Practices 11 Prevailing Breast Cancer Testing Policies and Practice 14 Mammogram Staff Statistics and Training and Certification 24 Mammogram Facilities interested in providing discount for a patient referral program 29 Assessment of Mammogram Centers by Researcher 31 Discussion and Conclusions 34 Recommendations 36 References 38 Annexes Survey Questionnaire and Assessment Tool 34 Private Market Mammogram Facilities 49 List of Figures Figure No. Description Page 1 Mammogram Service Initiation in the surveyed facilities 11 2 Breast Cancer Testing Practices – Patient Profiles for Ultrasound 15 3 Breast Cancer Testing Practices – Patient Profiles for Mammogram 15 4 Types of patients by referral seeking breast cancer testing 19 5 Sources of physician referred patients 19 6 Radiologists general interest in training in breast cancer screening and diagnosis at 27 KHCC 7 Preferred Training times for Radiologists 27 8 Possible Commitment forms from Facilities to training of staff on mammogram at 28 KHCC 9 Interest of surveyed centers in providing discount for a patient referral program 29 3 List of Tables Table Description Page No. -

Area Name Speciality Tel Bed Home Page Hospital(Amman)

Hospital(Amman) Area Name Speciality Tel Bed Home Page Abu Nseir Al-Rashid Hospital Center 523-3882 www.alrashid-hospital.com Balsam Hospital Consultancy 585-6856 Sweileh Al-Essra Hospital General 530-0300 125 www.essrahospital.com Al Urdon St.(Tabarbor Area) Queen Alia Military hospital General 515-7100 www.jrms.gov.jo North Jordan University Hospital General 535-3666 535 www.ju.edu.jo Queen Rania AlAbdullah St. King Hussein Cancer Center Cancer 535-3000 120 www.khcc.jo Ibn Al-Haitham Hospital General 551-6808 74 www.ibn-alhaytham-hospital.com Madina Munawara St. Eye Specialty Hospital Eye 551-1176 25 www.eyehosp.com Tla'Al-Ali Tla'Al-Ali Hospital General 533-9008 53 www.tlaa-alalihospital.com Marka Marka Islamic Speciality Hospital General 489-3855 38 www.islamic-hospital.org (Western and Northen Marka)Al-Mowasah Hospital General 489-6842 www.mowasah-hospital.com Al-Bashir Hospital General 475-3101 www.albashir-hospital.gov.jo Ashrafieh Jordan Red Crescent Hospital General 477-9131 126 www.jnrcs.org Down Town Italian Hospital General 477-7101 47 Istiklal St. Istiklal Hospital General 565-2600 114 www.istiklalhospital.com East Al Hashimi Prince Hamza Hospital General 505-3826/3814 650 Abdul Hadi Eye Hospital Eye 462-7628 17 www.ahhospital.com Jabal Amman Meternity Hospital Gyn-Obsterics 464-2362 15 Jabal Amman Malhas Hospital General 463-6140 69 Amman Surgical Hospital 464-1261 www.ammanhospital.com (Beween 3circle and 4circle) Al Khalidi Medical Center General 464-4281 160 www.kmc.jo (3Circle) Farah Maternity Hospital Gyn-Obsterics -

The Impact of Using E-Health on Patient Satisfaction from a Physician-Patient Relationship Perspective

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 19, 2020 THE IMPACT OF USING E-HEALTH ON PATIENT SATISFACTION FROM A PHYSICIAN-PATIENT RELATIONSHIP PERSPECTIVE This research is completed under patronage of Petra University Dr. Yasmin Sakka1, Dr. Dina Qarashay2 1Faculty of Administrative & Financial Sciences/Management, Information Systems Department/University of Petra 2Medical Health Center/University of Petra Received: 14 March 2020 Revised and Accepted: 8 July 2020 ABSTRACT: This study aims to determine how e-health impacts physician-patient relationship by evaluating patients’ perceptions in terms of trust, reliability, communication, service quality, time and cost, and control and improvement aspects of the relationship. The aggregate outcome of the study examines patient readiness to use electronic two-way communication between patient and physician in Jordanian healthcare sector. The theoretical model has been constructed post a review of related previous literature to identify the dependent and independent variables of the study. Data was collected by means of questionnaire survey of patients visiting private hospitals in Amman, Jordan using a simple random sampling method (N=344). The results of this research revealed that the perception of Jordanians of e-Health physician-patient relationship is significantly positive. This perception comes with the belief that e-Health will improve the relationship, save time and money and improve the quality of care. I. INTRODUCTION There is a wealth of research data that supports the benefits of effective communication and health outcomes for patients and healthcare teams. The connection that a patient feels with his physician can ultimately improve their health mediated through participation in their care, adherence to treatment, and patient self-management. -

Impact of Entrepreneurship in Achieving the Competitive Advantage, an Emperical Research in Private Hospitals in Amman, Jordan

IMPACT OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN ACHIEVING THE COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE, AN EMPERICAL RESEARCH IN PRIVATE HOSPITALS IN AMMAN, JORDAN by Mohammad Fayez Mohammad Abu Zaid A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in Business Administration at The University of Petra Amman-Jordan October /2013 I Authorization I am Mohammad Fayez Mohammad Abu Zaid. I authorize the University of Petra to make hard or soft copies of my thesis to libraries, institutions, and people when asked. Name: Mohammad Fayez Mohammad Abu Zaid Signature: ------------------------------- Date: ------------------------------------ II IMPACT OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN ACHIEVING THE COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE, AN EMPERICAL RESEARCH IN PRIVATE HOSPITALS IN AMMAN, JORDAN by Mohammad Fayez Mohammad Abu Zaid A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in Business Administration at The University of Petra Amman-Jordan October /2013 Major Supervisor Name Signture Prof. Najim Al- Azzawi ------------------- Examination Committee Name Signture 1. Prof. Musa Al- Lozi ------------------- 2. Dr. Sabah Hameed Agha ------------------- 3. Dr. Ahmed El- Qasem ------------------- III ABSTRACT IMPACT OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN ACHIEVING THE COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE, AN EMPERICAL RESEARCH IN PRIVATE HOSPITALS IN AMMAN, JORDAN by Mohammad Fayez Mohammad Abu Zaid at University of Petra, 2013 Under the supervision of Prof. Najim Al Azzawi The main objective of this research is to investigate the impact of entrepreneurship in achieving -

Curriculum Vitae Firas Saleh Daher Alfwaress, Ph.D., CCC/SLP

Curriculum Vitae Firas Saleh Daher Alfwaress, Ph.D., CCC/SLP Contact Information Vice Dean Audiology & Speech Pathology Department Faculty of Allied Health Sciences Jordan University of Science & Technology Irbid, Jordan [email protected] Cell: 0096279-5500599 Credentials - American Speech & Hearing Association: Certificate of Clinical Competence: # 12103394 since 2009 - Certified Speech Language Pathologist: Ministry of Health, Jordan, # 5 since 1994 Education University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA 2008 Doctor of Philosophy Major Area: Speech-Language Pathology Minor Area: Medical Speech Pathology Dissertation Title: “The Lombard Effect on Speech Clarity in Patients with Parkinson Disease” University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan 1994 Master of Arts Major Area: Communication Sciences & Disorders 1992 Bachelor of Science Major Area: Nursing Deir Abi Said Higher School, Irbid, Jordan 1986 High School: Scientific Stream 1 Practicum Training Head & neck dissection of cadavers in the anatomy labs at the medical school, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA Observation of Bronchoscopy procedure at the University of Cincinnati Hospital & Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA Practicum training at nursing homes in Cincinnati area, Ohio, USA Hearing screening for head start and elementary school students in Ohio, Indiana, & Kentucky states, USA On-hand training on video stroboscopic examination of the vocal folds at the speech pathology clinics, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA Clinical internship in speech-language pathology -

Feasibility of Building an American Private Hospital in Jordan

European Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 1450-2267 Vol. 40 No 2 September, 2013, pp.312-329 http://www.europeanjournalofsocialsciences.com Investment Opportunities in Health: Feasibility of Building an American Private Hospital in Jordan Ibrahim Alabbadi Corresponding Author, MBA, PhD Associate Professor Department of Biopharmaceutics and Clinical Pharmacy Faculty of Pharmacy, The University of Jordan, Jordan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 962-6-5355000-23356; Fax: 962-6-5300250 Azmi Mahafza Professor, Dean, Faculty of Medicine The University of Jordan, Jordan Mousa A. Al-Abbadi Professor, East Tennessee State University & James H. Quillen Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Mountain Home, TN 37684, USA Amir Bakir Associate Professor, Department of Economics Faculty of Business, The University of Jordan, Jordan Abstract Jordan has one of the most modern health care infrastructures in the Middle East with an encouraging investment climate, thus a potential country to offer high quality health services at reasonable prices at a time in which medical care is becoming very costly in North America, Europe and the Middle East.The aim of this study was to investigate the value of health of establishing a high standard American private hospital as an investment opportunity in Jordan. This feasibility study cost estimates that are related to the project for 400 beds hospital consists of four components: market study, technical study,financial study and risk analysis. Investment, running and personnel costs in addition to estimated revenues and cash flows were calculated. The viability of the project was assessed by two indicators, net present value (NPV) at a chosen discount rate which equals the opportunity cost of capital, normally taken as 10%, and the internal rate of return (IRR). -

Jordan Competitiveness Program Quarterly Report October – December 2014

JORDAN COMPETITIVENESS PROGRAM QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2014 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. JORDAN COMPETITIVENESS PROGRAM QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER – DECEMBER 2014 Program Title: Jordan Competitiveness Program Sponsoring USAID Office: Economic Development and Energy Contract Number: AID-278-C-13-00005 Contractor: DAI Date of Publication: 15 January 2015 Author: USAID JCP Staff The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. II USAID JCP QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2014 CONTENTS CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................. I ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................... II EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................ 5 1: CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................................ 10 CLEAN TECHNOLOGY ............................................................................................................. 10 HEALTHCARE AND LIFE SCIENCES ......................................................................................... 17 ICT SECTOR ........................................................................................................................ -

Conference Booklet

UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF His Majesty King Abdullah II ibn Al Hussein THE 3rd QUALITY HEALTH CARE Building Quality For Safer Healthcare Quality... An Integrated Approach Successes Provider & Services s n S o y i t s p t e e m c r s e P Governance Patient & Management & Community Challenges Conference Booklet Diamond Sponsor Booklet Sponsor 23rd – 25th November 2015 His Majesty King Abdullah II ibn Al Hussein rd The 3 Health Care Conference and Exhibition – HCAC 2015 THE 3rd QUALITY HEALTH CARE Table of Contents Welcoming Letter ...............................................................................................................7 About HCAC .........................................................................................................................8 About the Conference .......................................................................................................9 Conference Committees ..................................................................................................11 Conference Workshops ....................................................................................................12 Simultaneous Pre-Conference Workshops Program ................................................14 Conference Session Descriptions ..................................................................................15 Conference Scientific Program .......................................................................................17 Conference Floor Plan .......................................................................................................20 -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Nijmeh Al-Atiyyat, PhD, MSC, RN, BC Advanced Nurse Specialist /Nursing Master Education –Oncology Mentor of Oncology Nursing Program ORCID: 0000-0002-6519-5481 CONTACT INFORMATION Address Telephone Email Amman-Jordan +962-797382220 [email protected] aw9594@ hotmail.com EDUCATION Date Degree Institution and location 2006-2009- PhD in Nursing (Cancer Pain Management) - Wayne State University, Michigan, U.S.A 1996-1998- M.SC of Nursing- University of Jordan, Amman –Jordan 1990-1994- B.SC of Nursing- University of Jordan, Amman –Jordan TEACHING EXPERIENCE Date Position Institution and location 2009- Present- Assistant Professor- Mentor of Oncology Nursing Master Program- Faculty of Nursing, Hashemite University, Zarka –Jordan 2010-2014- Acting Dean- Assistant Professor- Faculty of Nursing, Hashemite University, Zarka – Jordan 2012-2014- Chair of Adult Health Department - Faculty of Nursing, Hashemite University, Zarka– Jordan 2009- 2010- Assistant Dean - Assistant Professor- Faculty of Nursing, Hashemite University, Zarka –Jordan Curriculum Vitae- Dr. Al-Atiyyat Page 1 Printed by BoltPDF (c) NCH Software. Free for non-commercial use only. 2004 – 2006 - Teaching and Research Assistant - Faculty of Nursing, Hashemite University, Zarka –Jordan 2004 - Lecturing on Death and Dying - Arab Medical Center, Amman - Jordan 2004 - Lecturing on Palliative Care - Arab Medical Center, Amman - Jordan 2004 - Lecturing on Pain Management - Arab Medical Center, Amman - Jordan 2004 - Lecturing on Preceptorship/Mentorship of Nursing Students