Carpenter Ants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sperm Use During Egg Fertilization in the Honeybee (Apis Mellifera) Maria Rubinsky SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2010 Sperm Use During Egg Fertilization in the Honeybee (Apis Mellifera) Maria Rubinsky SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Rubinsky, Maria, "Sperm Use During Egg Fertilization in the Honeybee (Apis Mellifera)" (2010). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 914. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/914 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sperm use during egg fertilization in the honeybee (Apis mellifera) Maria Rubinsky November, 2010 Supervisors: Susanne Den Boer, Boris Baer, CIBER; The University of Western Australia Perth, Western Australia Academic Director: Tony Cummings Home Institution: Brown University Major: Human Biology- Evolution, Ecosystems, and Environment Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Australia: Rainforest, Reef, and Cultural Ecology, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2010 Abstract A technique to quantify sperm use in honeybee queens (Apis mellifera) was developed and used to analyze the number of sperm used in different groups of honeybee queens. To do this a queen was placed on a frame with worker cells containing no eggs, and an excluder box was placed around her. The frame was put back into the colony and removed after two and a half hours. -

Comparison Between the Microbial Diversity in Carpenter Ant (Camponotus) Gut and Weaver Ant (Oecophylla) Gut

Hosmath & Timmappa J Pure Appl Microbiol, 13(4), 2421-2436 | December 2019 Article 5857 | https://doi.org/10.22207/JPAM.13.4.58 Print ISSN: 0973-7510; E-ISSN: 2581-690X RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Comparison Between the Microbial Diversity in Carpenter Ant (Camponotus) Gut and Weaver Ant (Oecophylla) Gut Kirti Shivayogi Hosmath and Shivasharana Chandrabanda Timmappa* Department of Microbiology and Biotechnology, Karnatak University, Dharwad, Karnataka, India. Abstract Aim to study the whole genome of cultured and uncultured microbes present within the ant gut environment can only be determined by using the advanced technology used is Next-generation sequencing (NGS) tool. Here' in this research' this tool is been used to study the exact composition or population of gut microbes present in the two ants are: Carpenter ant (genus Camponotus) and Weaver ant (genus Oecophylla), by 16S/18S/ITS rDNA amplicon sequencing and comparing whether these two ants have same microbial species and same composition, if yes then what is their percentage of abundance in these ants gut and how these microbial diversity play role in these ants life cycle. And from this ant gut study, which is performed by metagenomic tools, revealed the presence of large diversity of microbes in these ant gut and are from the order and genus of bacteria commonly found are Actinomycetales, Bifidobacteriales, Actinobacteria, Bacteriodales, Flavobacteriales, Caulobacterales, Methanobacteriales, Lactobacillales, Clostridiales, Bradyrhizobacterium, Agrobacterium etc. here, the complete microbial diversity of Carpenter and Weaver ant guts are studied by performing 16S / 18S / ITS rDNA amplicon sequencing procedure, which includes, surface sterilization, dissection, culturing in basic media broth, genomic DNA extraction, quality control, rDNA variable region amplification, library construction, high-throughput sequencing, data analysis and identification of microbiome. -

Nutritional Ecology of the Carpenter Ant Camponotus Pennsylvanicus (De Geer): Macronutrient Preference and Particle Consumption

Nutritional Ecology of the Carpenter Ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus (De Geer): Macronutrient Preference and Particle Consumption Colleen A. Cannon Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology Richard D. Fell, Chairman Jeffrey R. Bloomquist Richard E. Keyel Charles Kugler Donald E. Mullins June 12, 1998 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: diet, feeding behavior, food, foraging, Formicidae Copyright 1998, Colleen A. Cannon Nutritional Ecology of the Carpenter Ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus (De Geer): Macronutrient Preference and Particle Consumption Colleen A. Cannon (ABSTRACT) The nutritional ecology of the black carpenter ant, Camponotus pennsylvanicus (De Geer) was investigated by examining macronutrient preference and particle consumption in foraging workers. The crops of foragers collected in the field were analyzed for macronutrient content at two-week intervals through the active season. Choice tests were conducted at similar intervals during the active season to determine preference within and between macronutrient groups. Isolated individuals and small social groups were fed fluorescent microspheres in the laboratory to establish the fate of particles ingested by workers of both castes. Under natural conditions, foragers chiefly collected carbohydrate and nitrogenous material. Carbohydrate predominated in the crop and consisted largely of simple sugars. A small amount of glycogen was present. Carbohydrate levels did not vary with time. Lipid levels in the crop were quite low. The level of nitrogen compounds in the crop was approximately half that of carbohydrate, and exhibited seasonal dependence. Peaks in nitrogen foraging occurred in June and September, months associated with the completion of brood rearing in Camponotus. -

Analysis of Honeybee Drone Activity During the Mating Season in Northwestern Argentina

insects Article Analysis of Honeybee Drone Activity during the Mating Season in Northwestern Argentina Maria Marta Ayup 1,2,3 , Philipp Gärtner 3, José L. Agosto-Rivera 4, Peter Marendy 5,6 , Paulo de Souza 5,7 and Alberto Galindo-Cardona 1,8,* 1 National Scientific and Technical Research Council, CONICET, CCT, Tucumán 4000, Argentina; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Natural Sciences, National University of Tucumán (UNT), Tucumán 4000, Argentina 3 IER (Regional Ecology Institute), CONICET, Tucumán 4000, Argentina; [email protected] 4 Rio Piedras Campus, University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras 00927, Puerto Rico; [email protected] 5 Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, CSIRO, Canberra 2601, Australia; [email protected] (P.M.); paulo.desouza@griffith.edu.au (P.d.S.) 6 School of Technology, Environments and Design, University of Tasmania, Tasmania 7000, Australia 7 School of Information and Communication Technology, Griffith University, Nathan 4111, Australia 8 Miguel Lillo Foundation, Tucumán 4000, Argentina * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +54-0381-640-8826 Simple Summary: When we think of social insects, we mostly neglect males and their biology. Honeybee males or drones are an example. Like queens, drones are founders of the colony, but unlike queens and workers, their activity is not well-known. Drones exit the hive to mate as their only goal, in spite of the high chances of getting lost, being preyed upon and starving; and only if they are lucky, they will die when mating. These nuptial flights take place in Drone Congregation Areas during Citation: Ayup, M.M.; Gärtner, P.; spring and summer, and we know that their exit time is in the afternoons. -

HOUSEHOLD ARTHROPODS Nuisance Household Jean R

2015 Household Pests 2/22/2015 OVERVIEW Guidelines & Principles Groups of pests Public health pests HOUSEHOLD ARTHROPODS Nuisance Household Jean R. Natter Structural pests 2015 2 MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES DETERMINE MANAGEMENT Define the problem Eradicate? Damage? Critter(s)? Control? ID the critter Manage? Pest? Tolerate? Dangerous? (people, pets, or structures?) Did it just stumble indoors? Verify: PNW Insect Management Handbook Appropriate management 3 4 CAPTURE THE CRITTER RECOMMENDATIONS Research-based management EPA says: Pest control materials must be labeled for that purpose * * * * * * * * * * (Common Sense Pest Control) No home remedies 5 6 Jean R. Natter 2015 Household Pests 1 2015 Household Pests 2/22/2015 PUBLIC HEALTH: BED BUGS 3/16” Broadly flat, oval Cracks, crevices, & PUBLIC HEALTH PESTS seams (naturephoto.cz.com) Eggs glued in place Blood feeders (Bed Bugs; WSU; FS070E) Bites w/o pain Odor: sweet; acrid Bed Bugs (FS070E) 7 (J. R. Natter) 8 MANAGEMENT: BED BUGS PUBLIC HEALTH: MOSQUITOES Key Points Mattress: Encase or heat Rx Launder bedding, clothes – hot! Pest control company (NY Times) (L & R: University of Missouri; gambusia Stamford University) 9 10 MANAGEMENT: MOSQUITOES PUBLIC HEALTH: FLEAS Key Points Adults on animal Eggs drop off Source reduction Larvae ½” Personal protection w/tan head Mosquito fish (Gambusia), if legal Larvae eat debris Rx for larvae: Bti Pupa “waits” (Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis) Nest parasites (University of Illinois) 11 12 Jean R. Natter 2015 Household Pests 2 2015 Household Pests 2/22/2015 MANAGEMENT: FLEAS PUBLIC HEALTH: TICKS Rocky Mountain wood tick Key Points 3-step program Dermacentor species 1. Vacuum often East of Cascades 2. Insect growth regulator (IGR) Immatures feed mostly on carpet & pet’s “nest” on rodents 3. -

Carpenter Ants

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE R E S E A R C H & E X T E N S I O N University of Arkansas System Agriculture and Natural Resources FSA7013 Carpenter Ants John D. Hopkins Identification Associate Professor and Carpenter ants (Figure 1) Extension Entomologist are among the largest of the common ants seen in Kelly M. Loftin Arkansas. They are a nuisance by their presence when found Associate Professor and inside the home. They do Extension Entomologist not eat wood, but remove quantities of it to expand their nest size, sometimes causing structural damage. Winged forms are called Figure 1. Carpenter ant (worker) alates with winged males being smaller than winged females. Wingless queens measure 5/8 inch, winged queens 3/4 inch, large major workers 1/2 inch and small minor workers 1/4 inch. Color varies with species ranging from black to red with some species being a combination of both. Workers are usually reddishbrown to black in coloration. Workers have large heads and a small thorax, while adult swarmers have a smaller head and large Figure 2. Carpenter ants have a single node on the thorax. The petiole has one petiole, and the thorax has a rounded upper node, and the profile of the surface. thorax, in workers only, has an evenly rounded upper surface (Figure 2). People sometimes confuse carpenter ants with termites. These ants usually nest in logs, Termite workers are small, 1/8 to stumps, hollow trees or decayed wood, 3/16 inch long, white and do not run but may be found nesting in sound freely over unexposed surfaces. -

Carpenter Ants It an Ant Or Termite?" If You Are Still Unsure After Reading Methods

CARPENTER ANT... Ants are social insects, living in groups Cornell Cooperative Extension called nests or colonies. They undergo U r b a n I P M P r o g r a m OR TERMITE, OR ...? complete metamorphosis, developing into Information Sheet No. 601 egg, larva, pupa, then adult. Colony members can be separated into groups The black carpenter ant (Camponotus pennsylvanicus) is called "castes" by the roles that they play in Integrated Pest often the species that damages houses in the Northeast. the colony's survival, such as reproductive References and Further Reading It has a single node (waist segment) and is 1/4 to more Management for or worker. than 1/2 inch long. It does not have a stinger, but it can The reproductives consist of the queen Klass, C. and D. Karasevicz. 1995. Pest bite. A frequently asked question about these ants is, "Is and the male ants. The male ants fertilize the queen during the ant's nuptial flight, Management Around the Home: Cultural Carpenter Ants it an ant or termite?" If you are still unsure after reading Methods. Miscellaneous Bulletin S74. Cornell the information below, consult Cornell Cooperative then die. The queen finds a secluded site, chews off her wings, and starts to build a Cooperative Extension, Ithaca, NY WHAT TO DO NOW Extension. colony. The queen cares for her first group Lifton, B. 1991. Bug Busters: Poison-Free Pest of offspring through the egg, larval, and Controls for Your House & Garden. Avery Identify the insect. If you are Antennae not “elbowed” pupal stages by herself. -

Carpenter Ants and Their Control

Carpenter Ants and Their Control Of the approximately 100 different species of ants Carpenter Ant Habits found in Iowa, the most destructive are the carpenter Carpenter ants are social insects that live in colonies. ants. Most carpenter ants are large and shiny black, Each colony lives in a nest of large, irregular chambers although some species are dark brown or reddish and and tunnels excavated inside stumps, logs, hollow medium sized. These ants can cause major structural trees, dead limbs, posts, poles, porch columns, window damage when they tunnel in wood to construct their and door frames, building framing, and other wood. nests. Carpenter ants prefer wood that is naturally soft or wood that has been softened by decay (wood rot). Identifying Carpenter Ants Moisture and decay facilitate initial tunneling by Carpenter ants are some of the largest ants commonly the ants, but are not required for nesting. Nests may found in Iowa. They vary in length from 1/4 inch (6 extend into dry, sound lumber. Carpenter ants may mm) for the smallest worker to 3/4 inch (18 mm) for nest in existing cavities such as hollow doors or in a queen. All have constricted (i.e., wasplike) waists, spaces around windows and doors. elbowed antennae, and large abdomens, and some have wings (Figure 1). Unlike the nests of termites and wood-boring beetles, carpenter ant galleries are free of soil and debris, and Wingless worker carpenter ants are distinguished from are mostly free of sawdust. The walls of the nests other ant species by the smoothly arched shape of the are usually very smooth and clean. -

Black Carpenter Ants in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas: Relationships with Prescribed Fire, Site and Stand Variables, and Red Oak Borer

BLACK CARPENTER ANTS IN THE OZARK MOUNTAINS OF ARKANSAS: RELATIONSHIPS WITH PRESCRIBED FIRE, SITE AND STAND VARIABLES, AND RED OAK BORER BLACK CARPENTER ANTS IN THE OZARK MOUNTAINS OF ARKANSAS: RELATIONSHIPS WITH PRESCRIBED FIRE, SITE AND STAND VARIABLES, AND RED OAK BORER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology By ROBIN MICHELLE VERBLE University of Southern Indiana Bachelor of Science in Biophysics, 2006 August 2008 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT Black carpenter ants, Camponotus pennsylvanicus DeGeer, are nearly ubiquitous in eastern North American forests. These ants are documented as predators of red oak borer, Enaphalodes rufulus Haldeman, a native longhorn beetle that underwent an unprecedented population increase and decline in the oak hickory forests of the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas from the late 1990’s to 2005. My objective was to examine red oak borer emergence holes and site aspects and correlate these forest and tree attributes with presence or absence of black carpenter ants. Historic red oak borer population data, tree REP class and site aspects for 13 separate plots were used. At each site, all red oaks >10 cm DBH were baited for black carpenters ants using a mixture of tuna in oil and honey. Black carpenter ants are more likely to be found on trees with low levels of previous red oak borer infestation versus those trees with previously high levels of infestation. These results may suggest black carpenter ants play a role in controlling red oak borer populations. Distribution of black carpenter ants in red oaks prior to and during the outbreak is unknown. -

The Coexistence

Myrmecological News 13 37-55 2009, Online Earlier Natural history and phylogeny of the fungus-farming ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) Natasha J. MEHDIABADI & Ted R. SCHULTZ Abstract Ants of the tribe Attini comprise a monophyletic group of approximately 230 described and many more undescribed species that obligately depend on the cultivation of fungus for food. In return, the ants nourish, protect, and disperse their fungal cultivars. Although all members of this tribe cultivate fungi, attine ants are surprisingly heterogeneous with regard to symbiont associations and agricultural system, colony size and social structure, nesting behavior, and mating system. This variation is a key reason that the Attini have become a model system for understanding the evolution of complex symbioses. Here, we review the natural-history traits of fungus-growing ants in the context of a recently published phylo- geny, collating patterns of evolution and symbiotic coadaptation in a variety of colony and fungus-gardening traits in a number of major lineages. We discuss the implications of these patterns and suggest future research directions. Key words: Hymenoptera, Formicidae, fungus-growing ants, leafcutter ants, colony life, natural history, evolution, mating, agriculture, review. Myrmecol. News 13: 37-55 (online xxx 2008) ISSN 1994-4136 (print), ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Received 12 June 2009; revision received 24 September 2009; accepted 28 September 2009 Dr. Natasha J. Mehdiabadi* (contact author) & Dr. Ted R. Schultz* (contact author), Department of Entomology and Laboratories of Analytical Biology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, NHB, CE518, MRC 188, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] * Both authors contributed equally to the work. -

Ąnts Are Tiny-But-Tough Insects That Show up for Work Almost Anytime

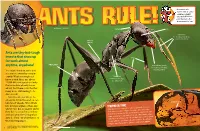

A scientist who studies ants is called a myrmecologist (mur-muh-KAH-luh- jist). Myrmex is the AnTs RULE! Greek word for “ant.” by Ellen Lambeth HEAD eye antennas for feeling, smelling, communicating petiole (waist) Ąnts are tiny-but-tough insects that show up legs for work almost anytime, anywhere! ABDOMEN mandibles (jaws) for cutting, holding, You might think an ant is just digging, biting a common, everyday creepy- crawly. What you might not THORAX where all six legs know is that there are about are attached 12,000 different species of ants that scientists already know about. And there could be that many more still waiting to be discovered! Ants live all over the globe except in Antarctica and on cer- tain far-off islands. More kinds winged ant live in tropical places than any- Trapped in Time where else. But no matter where Ants have been around for about 120 million years. they live, you can be sure they You can see some of these long-ago ants in fossils. are hard at work—doing what Sometimes an ant would accidentally crawl or fly into some oozing tree sap and get stuck. (Ants have wings ants do. Find out what that is on only when it’s time to fly off and find mates.) The hunk the following pages. of sap with the ant inside slowly hardens. Eventually it turns into this golden, glassy fossil called amber. FRANCISCO JAVIER TORRENT ANDRES/V&W/SEAPICS.COM (6TL) >; PIOTR NASKRECKI (6-7); JOHN DOWNER/NPL/MINDEN PICTURES (7BR); 6 ART BY SCOTT NEELY claws 7 Most insects are solitary, which means they THE SECRET LIVES live alone. -

Foraging Ants Trade Off Further for Faster: Use of Natural Bridges and Trunk Trail Permanency in Carpenter Ants

Naturwissenschaften (2013) 100:957–963 DOI 10.1007/s00114-013-1096-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Foraging ants trade off further for faster: use of natural bridges and trunk trail permanency in carpenter ants Raquel G. Loreto & Adam G. Hart & Thairine M. Pereira & Mayara L. R. Freitas & David P. Hughes & Simon L. Elliot Received: 15 June 2013 /Revised: 22 August 2013 /Accepted: 24 August 2013 /Published online: 11 September 2013 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Abstract Trail-making ants lay pheromones on the substrate composed of bridges, are maintained for months, so they can to define paths between foraging areas and the nest. Combined be characterized as trunk trails. We suggest that pheromone- with the chemistry of these pheromone trails and the physics based foraging trail networks in field conditions are likely to of evaporation, trail-laying and trail-following behaviours be structured by a range of potentially complex factors but that provide ant colonies with the quickest routes to food. In even then, speed remains the most important consideration. relatively uniform environments, such as that provided in many laboratory studies of trail-making ants, the quickest Keywords Foraging trail . Trunk trail . Carpenter ant . route is also often the shortest route. Here, we show that Optimal foraging carpenter ants (Camponotus rufipes), in natural conditions, are able to make use of apparent obstacles in their environ- ment to assist in finding the fastest routes to food. These ants Introduction make extensive use of fallen branches, twigs and lianas as bridges to build their trails. These bridges make trails signif- In pheromone-based foraging trail networks such as those found icantly longer than their straight line equivalents across the in Camponotus (Jaffe and Sanchez 1984), Solenopsis (Wilson forest floor, but we estimate that ants spend less than half the 1962) and the leaf-cutting ants Atta (Evison et al.