The Wigan Board of Guardians and the Administration of the Poor Laws 1880-1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scandal, Child Punishment and Policy Making in the Early Years of the New Poor Law Workhouse System

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository ‘Great inhumanity’: Scandal, child punishment and policy making in the early years of the New Poor Law workhouse system SAMANTHA A. SHAVE UNIVERSITY OF LINCOLN ABSTRACT New Poor Law scandals have usually been examined either to demonstrate the cruelty of the workhouse regime or to illustrate the failings or brutality of union staff. Recent research has used these and similar moments of crisis to explore the relationship between local and central levels of welfare administration (the Boards of Guardians in unions across England and Wales and the Poor Law Commission in Somerset House in London) and how scandals in particular were pivotal in the development of further policies. This article examines both the inter-local and local-centre tensions and policy conseQuences of the Droxford Union and Fareham Union scandal (1836-37) which exposed the severity of workhouse punishments towards three young children. The paper illustrates the complexities of union co-operation and, as a result of the escalation of public knowledge into the cruelties and investigations thereafter, how the vested interests of individuals within a system manifested themselves in particular (in)actions and viewpoints. While the Commission was a reactive and flexible welfare authority, producing new policies and procedures in the aftermath of crises, the policies developed after this particular scandal made union staff, rather than the welfare system as a whole, individually responsible for the maltreatment and neglect of the poor. 1. Introduction Within the New Poor Law Union workhouse, inmates depended on the poor law for their complete subsistence: a roof, a bed, food, work and, for the young, an education. -

Reforming Local Government in Early Twentieth Century Ireland

Creating Citizens from Colonial Subjects: Reforming Local Government in Early Twentieth Century Ireland Dr. Arlene Crampsie School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Policy University College Dublin ABSTRACT: Despite the incorporation of Ireland as a constituent component of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland through the 1801 Act of Union, for much of the early part of the nineteenth century, British policy towards Ireland retained its colonial overtones. However, from the late 1860s a subtle shift began to occur as successive British governments attempted to pacify Irish claims for independence and transform the Irish population into active, peaceful, participating British citizens. This paper examines the role played by the Local Government (Ireland) Act of 1898 in affecting this transformation. The reform of local government enshrined in the act not only offered the Irish population a measure of democratic, representative, local self- government in the form of county, urban district, and rural district councils, but also brought Irish local government onto a par with that of the rest of the United Kingdom. Through the use of local and national archival sources, this paper seeks to illuminate a crucial period in Anglo-Irish colonial relations, when for a number of years, the Irish population at a local level, at least, were treated as equal imperial citizens who engaged with the state and actively operated as its locally based agents. “Increasingly in the nineteenth century the tentacles of the British Empire were stretching deep into the remote corners of the Irish countryside, bearing with them schools, barracks, dispensaries, post offices, and all the other paraphernalia of the … state.”1 Introduction he Act of Union of 1801 moved Ireland from the colonial periphery to the metropolitan core, incorporating the island as a constituent part of the imperial power of the United TKingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. -

Ajsl ,QJI 8Ji)9

ajsL ,QJI 8jI)9 MINSTRY OF SOCIAL AFFAIRS L",uitom cz4 /ppaLf ('"oduaDon P'"zuocz1 Volume 2 TAILORING //, INTEGRATED SOCIAL SERVICES PROJECT aLSioJ 8jsto!*14I 3toj3JI J54o 4sjflko MINSTRY OF SOCIAL AFFAIRS cwitom c92/I/2a'LEf ?'oduation 57P/D 0 E15 ('uvzicul'um JoL CSPP nstzucto~ Volume 2 TAILORING g~jji~JI 6&= z#jJEi l tl / INTEGRATED SOCIAL SERVICES PROJECT wotsoi stoim 1oj3jw jsi.Lo 6suJf PREFACE The material which follows is .J l.a ,,h &*.aJIL& . part of a five volume series assem bled by the faculty and students of . 3aJ e~- t.l. -, r'- ,tY.. the University of North Carolina at L_:J q L--, X4 0-j VO Greensboro, Department of Clothing and Textiles, CAPP Summer Program. The CAPP, Custom Appar,1 Production LFJI L,4.," ,'"i u .U. J l Process, Program was initiated in Egypt as a part of the Integrated Social Services Project, Dr. Salah L-,S l k e. L C-j,,. El Din El Hommossani, Project Direc- - L0 C...J L'j tor, and under the sponsorship of 4 " r th Egyptian Ministry of Social !.Zl ij1.,1,,.B= r,L..,J1....J Affairs and the U.S. Agency for - .Jt , . -t. International Development. These materials were designed for use in . J L.Jt CSziJtAJI #&h* - L*J training CAPP related instructors t .L-- -- J and supervisors for the various programs of the Ministry of Social ._ . , .. .. Affairs and to provide such person- L , *i. l I-JL-j 6 h nel with a systematica,'ly organized und detailed curriculum plan which JL61tJ J..i..- J" could be verbally transferred to O| ->. -

Sew Any Fabric Provides Practical, Clear Information for Novices and Inspiration for More Experienced Sewers Who Are Looking for New Ideas and Techniques

SAFBCOV.qxd 10/23/03 3:34 PM Page 1 S Fabric Basics at Your Fingertips EW A ave you ever wished you could call an expert and ask for a five-minute explanation on the particulars of a fabric you are sewing? Claire Shaeffer provides this key information for 88 of today’s most NY SEW ANY popular fabrics. In this handy, easy-to-follow reference, she guides you through all the basics while providing hints, tips, and suggestions based on her 20-plus years as a college instructor, pattern F designer, and author. ABRIC H In each concise chapter, Claire shares fabric facts, design ideas, workroom secrets, and her sewing checklist, as well as her sewability classification to advise you on the difficulty of sewing each ABRIC fabric. Color photographs offer further ideas. The succeeding sections offer sewing techniques and ForewordForeword byby advice on needles, threads, stabilizers, and interfacings. Claire’s unique fabric/fiber dictionary cross- NancyNancy ZiemanZieman references over 600 additional fabrics. An invaluable reference for anyone who F sews, Sew Any Fabric provides practical, clear information for novices and inspiration for more experienced sewers who are looking for new ideas and techniques. About the Author Shaeffer Claire Shaeffer is a well-known and well- respected designer, teacher, and author of 15 books, including Claire Shaeffer’s Fabric Sewing Guide. She has traveled the world over sharing her sewing secrets with novice, experienced, and professional sewers alike. Claire was recently awarded the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award by the Professional Association of Custom Clothiers (PACC). Claire and her husband reside in Palm Springs, California. -

Wigan Local Development Framework Communities Evidence Review

Wigan Local Development Framework Communities Evidence Review June 2009 Wigan Council Environmental Services Contents Title Table A. National A1. Community Development Sustainable Communities – building for the future (2003) A1.1 Firm Foundations: The Governments Framework for Community Capacity A1.2 Building Better Public Building A1.3 The Role of Community Buildings A1.4 Strong and Prosperous Communities A1.5 Place Matters A1.6 Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Bill (December, A1.7 2008) The Children’s Plan: Building Brighter Futures A1.8 Living Places Prospectus A1.9 Sustainable Communities: People, Places and Prosperity (A Five A1.10 Year Plan) A2. Education and Learning Framework for the Future, Libraries, Learning and Information in the next A2.1 Decade Public Library Service Standards A2.2 Public Library Matters A2.3 Building Schools for the Future A2.4 Better Buildings, Better Design, Better Education A2.5 A3. Health NHS Local Improvement Finance Trust (LIFT) A3.1 Building on the Best A3.2 Design and neighbourhood healthcare buildings A3.3 Title Table A3.4 Physical Activity and the Environment A3.5 Tackling Obesities: The Foresight Report Health, place and nature: How outdoor environments influence health and A3.6 well-being: Knowledge base A3.7 Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives: A Cross Government Strategy for England A4. Demographics and social inclusion The Influence of Neighbourhood Deprivation on People’s Attachment to A4.1 Places A5. Community Safety and neighbourhoods Safer Places: The Planning System and Crime Prevention A5.1 B. Regional B1. Community Development Sustainable Communities in the North West B1 B2. Health Health Evidence Paper B2 C. -

Mapping Changes in Local News 2015-2017

Mapping changes in local news 2015-2017 More bad news for democracy? Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community (Bournemouth University) https://research.bournemouth.ac.uk/centre/journalism-culture-and-community/ Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power (King’s College London) http://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/policy-institute/CMCP/ Goldsmiths Leverhulme Media Research Centre (Goldsmiths, University of London) http://www.gold.ac.uk/media-research-centre/ Political Studies Association https://www.psa.ac.uk The Media Reform Coalition http://www.mediareform.org.uk For an electronic version of this report with hyperlinked references please go to: http://LocalNewsMapping.UK https://research.bournemouth.ac.uk/centre/journalism-culture-and-community/ For more information, please contact: [email protected] Research: Gordon Neil Ramsay Editorial: Gordon Neil Ramsay, Des Freedman, Daniel Jackson, Einar Thorsen Design & layout: Einar Thorsen, Luke Hastings Front cover design: Minute Works For a printed copy of this report, please contact: Dr Einar Thorsen T: 01202 968838 E: [email protected] Published: March 2017 978-1-910042-12-0 Mapping changes in local news 2015-2017: More bad news for democracy? [eBook-PDF] 978-1-910042-13-7 Mapping changes in local news 2015-2017: More bad news for democracy? [Print / softcover] BIC Classification: GTC/JFD/KNT/KNTJ/KNTD Published by: Printed in Great Britain by: The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community Dorset Digital Print Ltd Bournemouth University 16 Glenmore Business Park Poole, England Blackhill Road Holton Heath BH12 5BB Poole 2 Foreword Local newspapers, websites and associated apps The union’s Local News Matters campaign is are read by 40 million people a week, enjoy a about reclaiming a vital, vigorous press at the high level of trust from their readers and are the heart of the community it serves, owned and lifeblood of local democracy. -

'Great Inhumanity': Scandal, Child Punishment and Policy Making in the Early Years of the New Poor Law Workhouse System S

‘Great inhumanity’: Scandal, child punishment and policy making in the early years of the New Poor Law workhouse system SAMANTHA A. SHAVE UNIVERSITY OF LINCOLN ABSTRACT New Poor Law scandals have usually been examined either to demonstrate the cruelty of the workhouse regime or to illustrate the failings or brutality of union staff. Recent research has used these and similar moments of crisis to explore the relationship between local and central levels of welfare administration (the Boards of Guardians in unions across England and Wales and the Poor Law Commission in Somerset House in London) and how scandals in particular were pivotal in the development of further policies. This article examines both the inter-local and local-centre tensions and policy conseQuences of the Droxford Union and Fareham Union scandal (1836-37) which exposed the severity of workhouse punishments towards three young children. The paper illustrates the complexities of union co-operation and, as a result of the escalation of public knowledge into the cruelties and investigations thereafter, how the vested interests of individuals within a system manifested themselves in particular (in)actions and viewpoints. While the Commission was a reactive and flexible welfare authority, producing new policies and procedures in the aftermath of crises, the policies developed after this particular scandal made union staff, rather than the welfare system as a whole, individually responsible for the maltreatment and neglect of the poor. 1. Introduction Within the New Poor Law Union workhouse, inmates depended on the poor law for their complete subsistence: a roof, a bed, food, work and, for the young, an education. -

The Poor Law of 1601

Tit) POOR LA.v OF 1601 with 3oms coi3ii3rat,ion of MODSRN Of t3l9 POOR -i. -S. -* CH a i^ 3 B oone. '°l<g BU 2502377 2 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Chapter 1. Introductory. * E. Poor Relief before the Tudor period w 3. The need for re-organisation. * 4. The Great Poor La* of 1601. w 5. Historical Sketch. 1601-1909. " 6. 1909 and after. Note. The small figares occurring in the text refer to notes appended to each chapter. Chapter 1. .Introductory.. In an age of stress and upheaval, institutions and 9 systems which we have come to take for granted are subjected to a searching test, which, though more violent, can scarcely fail to be more valuable than the criticism of more normal times. A reconstruction of our educational system seems inevitable after the present struggle; in fact new schemes have already been set forth by accredited organisations such as the national Union of Teachers and the Workers' Educational Association. V/ith the other subjects in the curriculum of the schools, History will have to stand on its defence. -

IPSO Annual Statement for Jpimedia: 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020

IPSO annual statement for JPIMedia: 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020 1 Factual information about the Regulated Entity 1.1 A list of its titles/products. Attached. 1.2 The name of the Regulated Entity's responsible person. Gary Shipton, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of JPIMedia and Regional Director of its titles in the South of England, is the responsible person for the company. 1.3 A brief overview of the nature of the Regulated Entity. The regulated entity JPIMedia is a local and regional multimedia organisation in the UK as well as being a national publisher with The Scotsman (Scotland), The Newsletter (Northern Ireland) and since March 2021 nationalworld.com. We provide news and information services to the communities we serve through our portfolio of publications and websites - 13 paid-for daily newspapers, and more than 200 other print and digital publications. National World plc completed the purchase of all the issued shares of JPIMedia Publishing Limited on 2 January 2021. As a consequence, JPIMedia Publishing Limited and its subsidiaries, which together publish all the titles and websites listed at the end of this document, are now under the ownership of National World plc. We continue to set the highest editorial standards by ensuring that our staff are provided with excellent internally developed training services. The Editors' Code of Practice is embedded in every part of our editorial operations and we commit absolutely to the principles expounded by IPSO. JPIMedia continues to operate an internal Editorial Governance Committee with the key remit to consider, draft, implement and review the policies, procedures and training for the whole Group to ensure compliance with its obligations under IPSO. -

The Poor Law of Lunacy

The Poor Law of Lunacy: The Administration of Pauper Lunatics in Mid-Nineteenth Century England with special Emphasis on Leicestershire and Rutland Peter Bartlett Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University College London. University of London 1993 Abstract Previous historical studies of the care of the insane in nineteenth century England have been based in the history of medicine. In this thesis, such care is placed in the context of the English poor law. The theory of the 1834 poor law was essentially silent on the treatment of the insane. That did not mean that developments in poor law had no effect only that the effects must be established by examination of administrative practices. To that end, this thesis focuses on the networks of administration of the poor law of lunacy, from 1834 to 1870. County asylums, a creation of the old (pre-1834) poor law, grew in numbers and scale only under the new poor law. While remaining under the authority of local Justices of the Peace, mid-century legislation provided an increasing role for local poor law staff in the admissions process. At the same time, workhouse care of the insane increased. Medical specialists in lunacy were generally excluded from local admissions decisions. The role of central commissioners was limited to inspecting and reporting; actual decision-making remained at the local level. The webs of influence between these administrators are traced, and the criteria they used to make decisions identified. The Leicestershire and Rutland Lunatic asylum provides a local study of these relations. Particular attention is given to admission documents and casebooks for those admitted to the asylum between 1861 and 1865. -

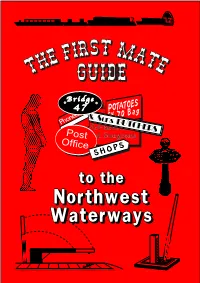

Post Office: with Stores, Without Stores Post Box - Only Shown If Nearer Than the Post Office Telephone Box Internet Cafe

GUIDE Bridge 47 & Sons BUTCHERS Phonecard McPherson PostDental Surgeons Office SHOPS 2 SYMBOLS USED IN THIS GUIDE Bank or Building Society BUSINESS Post Office: with stores, without stores Post Box - only shown if nearer than the Post Office Telephone Box Internet Cafe Doctors' Surgery WATERWAY Canal HEALTH Dental Surgery Towpath Veterinary Surgery Lock Hospital with A&E Bridge 14 Roadbridge Chemist (dispensing) Access Moorings Moorings TRANSPORT Bus Stop and Station Footpath Tram stop and Line Water * Railway Station and Line Rubbish * Petrol Station Toilet emptying * SHOPS Shops, not always shown individually Facility* block Self-serve Store or Supermarket *If absent from other guides FOOD Take-aways: General, Asian (Balti, Indian etc.) Chinese, Fish & Chips, Pizza 3 OTHER: Launderette Tourist Information Church Booking Passages 5 Adlington 93 Appley Bridge 60 Bridgewater Armley 136-137 Eccles 52 Barnoldswick 114-115 Leigh 54-55 Bingley 124-125 Patricroft 53 Blackburn - Worsley 53 Centre 99-101 Cherry Tree 97 Lock Equipment 32 Brierfield 108 Brighouse 36-37 Burnley 105-107 Elland 34-35 Burscough 62-63 Salterhebble 33 Chorley 94-95 Sowerby Bridge 30-31 Clayton 103 Colne 112 Huddersfield Canals Crossflatts 123 Ashton 50-51 Foulridge 113 Bradley 39 Gargrave 116-117 Huddersfield 40-41 Greengates 130-131 Marsden 44-45 Hapton 104 Slaithwaite 42-43 Haskayne 64 Stalybridge 48-49 Uppermill 46-47 Kirkstall 134-135 Leeds 139-141 Lancaster Liverpool - Centre 70-72 Ashton-on- Ribble 80-81 Liverpool - Eldonian 68-69 Bilsborrow 81 Litherland 67 Carnforth -

Government and Social Conditions in Scotland 1845-1919 Edited by Ian Levitt, Ph.D

-£e/. 54 Scs. S«S,/io SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FIFTH SERIES VOLUME 1 Government and Social Conditions in Scotland Government and Social Conditions in Scotland 1845-1919 edited by Ian Levitt, ph.d ★ EDINBURGH printed for the Scottish History Society by BLACKWOOD, PILLANS & WILSON 1988 Scottish History Society ISBN 0 906245 09 5 Printed in Great Britain ^ e ia O' >40 PREFACE A work of this kind, drawing on material from a wide variety of sources, could not have been possible without the active help and encouragment of many people. To name any individual is perhaps rather invidious, but I would like to draw special attention to the assistance given by the archivists, librarians and administrative officers of those authorities whose records I consulted. I would hope that this volume would in turn assist a wider understanding of what their archives and libraries can provide: they offer much for the history of Scotland. I must, however, record my special thanks to Dr John Strawhorn, who kindly searched out and obtained Dr Littlejohn’s report on Ayr (1892). I am greatly indebted to the following for their kind permission to use material from their archives and records: The Keeper of Records, the Scottish Record Office The Trustees of the National Library of Scotland The Archivist, Strathclyde Regional Council The Archivist, Ayr District Archives The Archivist, Edinburgh District Council The Archivist, Central Regional Council The Archivist, Tayside Regional Council Midlothian District Council Fife Regional Council Kirkcaldy District Council