Constraints on Foreign Journalists in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesus in China—Evan Osnos on an Upcoming Frontline Documentary

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 China Beat Archive 6-22-2008 Jesus in China—Evan Osnos on an Upcoming Frontline Documentary Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons "Jesus in China—Evan Osnos on an Upcoming Frontline Documentary" (2008). The China Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012. 205. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive/205 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the China Beat Archive at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Jesus in China—Evan Osnos on an Upcoming Frontline Documentary June 22, 2008 in Watching the China Watchers by The China Beat | No comments The Public Broadcasting Corporation’s Frontline series has a long tradition of airing documentaries on China. Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon’s prize-winning look at 1989, “The Gate of Heavenly Peace,” was shown as part of the series, for example, as was a later Tiananmen documentary, “The Tank Man.” And thanks to the online extras, from guides to further reading to lesson plans for teachers, the PBS Frontline site has become a valuable resource for those who offer classes or simply want to learn about the PRC. Still, it is rare (probably unprecedented) for two China shows to run back-to-back on Frontline. -

Some Legal Considerations for E.U. Based Mnes Contemplating High-Risk Foreign Direct Investments in the Energy Sector After Kiobel V

South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business Volume 9 Article 4 Issue 2 Spring 2013 Some Legal Considerations for E.U. Based MNEs Contemplating High-Risk Foreign Direct Investments in the Energy Sector After Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum and Chevron Corporation v. Naranjo Jeffrey A. Van Detta John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scjilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Van Detta, Jeffrey A. (2013) "Some Legal Considerations for E.U. Based MNEs Contemplating High-Risk Foreign Direct Investments in the Energy Sector After Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum and Chevron Corporation v. Naranjo," South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scjilb/vol9/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOME LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR E.U.- BASED MNES CONTEMPLATING HIGH- RISK FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENTS IN THE ENERGY SECTOR AFTER KIOBEL V. ROYAL DUTCH PETROLEUM AND CHEVRON CORPORATION V. NARANJO Jeffrey A. Van Detta* INTRODUCTION In a two-year span, two major multinational enterprises (MNEs) in the energy-sector—Chevron and Royal Dutch Petroleum—have experienced the opposite ends of a similar problem: The impact of civil litigation risks on foreign direct investments.1 For Chevron, it was the denouement of a two-decade effort to defeat a corporate campaign that Ecuadorian residents of a polluted oil-exploration region waged against it since 1993 and its predecessor, Texaco, first in the U.S. -

Annual Report 2015–2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2015–2016 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT 1 CONTENTS Reflections on the 2015–16 Season 2 Oscar S. Schafer, Chairman 4 Matthew VanBesien, President 6 Alan Gilbert, Music Director 8 Year at a Glance 10 Our Audiences 12 The Orchestra 14 The Board of Directors 20 The Administration 22 Conductors, Soloists, and Ensembles 24 Serving the Community 26 Education 28 Expanding Access 32 Global Immersion 36 Innovation and Preservation 40 At Home and Online 42 Social Media 44 The Archives 47 The Year in Pictures 48 The Benefactors 84 Lifetime Gifts 86 Leonard Bernstein Circle 88 Annual Fund 90 Education Donors 104 Heritage Society 106 Volunteer Council 108 Independent Auditor’s Report 110 2 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT THE SEASON AT A GLANCE Second Line Title Case Reflections on the 2015–16 Season 2 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT 3 REFLECTIONS ON THE 2015–16 SEASON From the New York Philharmonic’s Leadership I look back on the Philharmonic’s 2015–16 season and remember countless marvelous concerts that our audiences loved, with repertoire ranging from the glory of the Baroque to the excitement of the second NY PHIL BIENNIAL. As our Music Director, Alan Gilbert has once again brought excitement and inspiration to music lovers across New York City and the world. I also look back on the crucial, impactful developments that took place offstage. Throughout the season our collaboration with Lincoln Center laid a strong foundation for the renovation of our home. -

QCB May Postpone 100% Loan-Deposit Compliance Deadline Amid Liquidity Shortfall Issues

RBI CHIEF | Page 4 EMISSIONS ISSUE | Page 11 Aft er Rajan, VW ready with who? India $10bn plan; to search on devise fi x later Monday, June 20, 2016 Ramadan 15, 1437 AH EGYPT’S EXPENSIVE GRAIN: Page 3 World’s biggest GULF TIMES wheat buyer seen sowing confusion, BUSINESS reaping higher costs Gradual increase in QCB overnight QCB may postpone 100% deposit rate is ‘assumed’: MDPS loan-deposit compliance By Pratap John Chief Business Reporter Given the expected rate hikes by the Federal Reserve in the near term and the nature of the monetary policy under the Qatar Central Bank’s deadline amid liquidity (QCB) commitment to the exchange rate peg, a gradual increase in the QCB overnight deposit rate is assumed, the Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics (MDPS) has said. As Qatar’s currency is pegged to the US dollar, it has appreciated in both nominal and real effective terms since the middle of 2014, reducing imported shortfall issues: MDPS inflationary pressures, MDPS has said in its latest Qatar Economic Outlook (QEO) 2016-18. By Santhosh V Perumal The report said the nominal effective exchange rate Business Reporter (NEER) captures movements in bilateral exchange rates, weighted by respective volumes of trade flows. The NEER provides an accurate measure of iquidity issues may force the Qa- how the Qatari riyal is valued against the currencies tar Central Bank (QCB) to postpone of its major trading partners. The real effective Lthe deadline for compliance to 100% exchange rate (REER) adjusts for differential inflation loan-to-deposit ratio by one year to the end among its counterparts. -

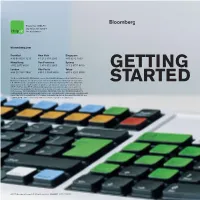

View the Bloomberg Terminal User Guide

Press the <HELP> key twice for instant Helpx2 live assistance. bloomberg.com Frankfurt New York Singapore +49 69 9204 1210 +1 212 318 2000 +65 6212 1000 Hong Kong San Francisco Sydney +852 2977 6000 +1 415 912 2960 +61 2 9777 8600 London São Paulo Tokyo GETTING +44 20 7330 7500 +55 11 3048 4500 +81 3 3201 8900 The BLOOMBERG PROFESSIONAL service, BLOOMBERG Data and BLOOMBERG Order Management Systems (the “Services”) are owned and distributed locally by Bloomberg Finance L.P. (“BFLP”) and its subsidiaries in all jurisdictions other than Argentina, Bermuda, China, India, STARTED Japan and Korea (the “BLP Countries”). BFLP is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bloomberg L.P. (“BLP”). BLP provides BFLP with all global marketing and operational support and service for the Services and distributes the Services either directly or through a non-BFLP subsidiary in the BLP Countries. BLOOMBERG, BLOOMBERG PROFESSIONAL, BLOOMBERG MARKETS, BLOOMBERG NEWS, BLOOMBERG ANYWHERE, BLOOMBERG TRADEBOOK, BLOOMBERG BONDTRADER, BLOOMBERG TELEVISION, BLOOMBERG RADIO, BLOOMBERG PRESS and BLOOMBERG.COM are trademarks and service marks of BFLP or its subsidiaries. ©2007 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. 26443337 1107 10006030 02 The Bloomberg Keyboard Keyboard and Navigation 04 Creating a Login Name and Password 06 Finding Information Autocomplete and the <HELP> Key 06 The Global Help Desk: 24/7 Interact with the Bloomberg Help Desk 08 Broad Market Perspectives Top Recommended Functions 09 Analyzing a Company Basic Functions for Bonds and Equities 10 Communication The BLOOMBERG PROFESSIONAL® Service Message System 11 Tips, Tricks, and Fun 12 Customer Support If you are not using a Bloomberg-provided keyboard, press the Alt + K buttons simultaneously to view an image of your keyboard. -

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online Table of Contents I. Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... 2 II. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 5 III. Background............................................................................................................................... 6 IV. Legislation .............................................................................................................................. 17 V. Ten Month Shutdown............................................................................................................... 33 VI. Detentions............................................................................................................................... 44 VII. Online Freedom for Uyghurs Before and After the Shutdown ............................................ 61 VIII. Recommendations................................................................................................................ 84 IX. Acknowledgements................................................................................................................. 88 Cover image: Composite of 9 Uyghurs imprisoned for their online activity assembled by the Uyghur Human Rights Project. Image credits: Top left: Memetjan Abdullah, courtesy of Radio Free Asia Top center: Mehbube Ablesh, courtesy of -

China's Global Media Footprint

February 2021 SHARP POWER AND DEMOCRATIC RESILIENCE SERIES China’s Global Media Footprint Democratic Responses to Expanding Authoritarian Influence by Sarah Cook ABOUT THE SHARP POWER AND DEMOCRATIC RESILIENCE SERIES As globalization deepens integration between democracies and autocracies, the compromising effects of sharp power—which impairs free expression, neutralizes independent institutions, and distorts the political environment—have grown apparent across crucial sectors of open societies. The Sharp Power and Democratic Resilience series is an effort to systematically analyze the ways in which leading authoritarian regimes seek to manipulate the political landscape and censor independent expression within democratic settings, and to highlight potential civil society responses. This initiative examines emerging issues in four crucial arenas relating to the integrity and vibrancy of democratic systems: • Challenges to free expression and the integrity of the media and information space • Threats to intellectual inquiry • Contestation over the principles that govern technology • Leverage of state-driven capital for political and often corrosive purposes The present era of authoritarian resurgence is taking place during a protracted global democratic downturn that has degraded the confidence of democracies. The leading authoritarians are ABOUT THE AUTHOR challenging democracy at the level of ideas, principles, and Sarah Cook is research director for China, Hong Kong, and standards, but only one side seems to be seriously competing Taiwan at Freedom House. She directs the China Media in the contest. Bulletin, a monthly digest in English and Chinese providing news and analysis on media freedom developments related Global interdependence has presented complications distinct to China. Cook is the author of several Asian country from those of the Cold War era, which did not afford authoritarian reports for Freedom House’s annual publications, as regimes so many opportunities for action within democracies. -

American Government (POL SC 1100) Spring 2019 Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, 2-2:50Pm 102 Naka Hall

POL SC 1100-1-1-1-1 American Government (POL SC 1100) Spring 2019 Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, 2-2:50pm 102 Naka Hall Jake Haselswerdt, PhD Assistant Professor Department of Political Science & Truman School of Public Affairs Office: 301 Professional Building Office hours: Tuesday, 2-4pm, and by appointment Email (preferred): [email protected] Phone: 573-882-7873 Syllabus updated February 15, 2019 Teaching Assistants Hyojong Ahn Dongjin Kwak Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Office: 315 Professional Building Office: 207 Professional Building Office hours: Monday, 10:30am-1:30pm; Office hours: Monday & Wednesday, Tuesday, 12:30pm-3:30pm 10am-1pm Course Overview & Goals This course offers an introduction to American politics and government from a political science perspective. While the course should increase your factual civic knowledge of American institutions, it is about more than that. Political science seeks to move beyond civic knowledge, to question and analyze the people, groups, events, institutions, policies, ideas, etc that we observe. Sometimes, our questions are empirical, meaning they deal with what is: Do Members of Congress support the policies their constituents want? Do political campaigns affect voters’ decisions? Sometimes, they are normative, meaning they deal with what should be: Is the U.S. Senate harmful to democracy because Wyoming has the same number of senators as California? Should the Constitution be amended so Supreme Court Justices no longer serve for life? In this course, we will consider both types of questions. 1 POL SC 1100-1-1-1-1 The success of democratic governments depends in part on the capacity of their citizens to hold them accountable. -

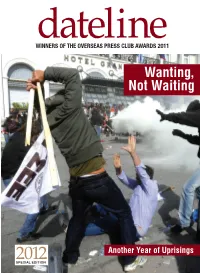

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

New China and Its Qiaowu: the Political Economy of Overseas Chinese Policy in the People’S Republic of China, 1949–1959

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science New China and its Qiaowu: The Political Economy of Overseas Chinese policy in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1959 Jin Li Lim A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2016. 2 Declaration: I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,700 words. 3 Abstract: This thesis examines qiaowu [Overseas Chinese affairs] policies during the PRC’s first decade, and it argues that the CCP-controlled party-state’s approach to the governance of the huaqiao [Overseas Chinese] and their affairs was fundamentally a political economy. This was at base, a function of perceived huaqiao economic utility, especially for what their remittances offered to China’s foreign reserves, and hence the party-state’s qiaowu approach was a political practice to secure that economic utility. -

The International Media Coverage of China: Too Narrow an Agenda?

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford The international media coverage of China: Too narrow an agenda? by Daniel Griffiths Michaelmas Term 2013 Sponsor: BBC 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors, James Painter and Rana Mitter, for their help and advice with this research. I am also very grateful to the staff at the Reuters Institute and the other Fellows for making my time at Oxford so interesting and enjoyable. Finally, a big thank you goes to my family for all their love and support. 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 7 2. Literature Review 9 3. Methodology 10 4. Results 12 5. Conclusions and Recommendations 18 Bibliography 20 Appendix: Articles in Content Analysis 21 3 Executive Summary China is an increasingly important player in global affairs but there is very little research on how it is presented in the international media. This matters because even in today's increasingly interconnected world the media can often influence our perceptions of other countries. This study presents a content analysis of news stories about China in the online editions of the New York Times, BBC News, and the Economist over two separate weeks in the autumn of 2013. In total, 129 stories were analysed. Due to the time constraints of a three month fellowship it was not possible to compile a broader data set which might have offered greater insights. So this paper should not be seen as a definitive study. Instead, it is a snapshot intended to open a discussion about representations of China in the global media and pave the way for further research. -

Deng Xiaoping in the Making of Modern China

Teaching Asia’s Giants: China Crossing the River by Feeling the Stones Deng Xiaoping in the Making of Modern China Poster of Deng Xiaoping, By Bernard Z. Keo founder of the special economic zone in China in central Shenzhen, China. he 9th of September 1976: The story of Source: The World of Chinese Deng Xiaoping’s ascendancy to para- website at https://tinyurl.com/ yyqv6opv. mount leader starts, like many great sto- Tries, with a death. Nothing quite so dramatic as a murder or an assassination, just the quiet and unassuming death of Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In the wake of his passing, factions in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) competed to establish who would rule after the Great Helmsman. Pow- er, after all, abhors a vacuum. In the first corner was Hua Guofeng, an unassuming functionary who had skyrocketed to power under the late chairman’s patronage. In the second corner, the Gang of Four, consisting of Mao’s widow, Jiang September 21, 1977. The Qing, and her entourage of radical, leftist, Shanghai-based CCP officials. In the final corner, Deng funeral of Mao Zedong, Beijing, China. Source: © Xiaoping, the great survivor who had experi- Keystone Press/Alamy Stock enced three purges and returned from the wil- Photo. derness each time.1 Within a month of Mao’s death, the Gang of Four had been imprisoned, setting up a showdown between Hua and Deng. While Hua advocated the policy of the “Two Whatev- ers”—that the party should “resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave”—Deng advocated “seek- ing truth from facts.”2 At a time when China In 1978, some Beijing citizens was reexamining Mao’s legacy, Deng’s approach posted a large-character resonated more strongly with the party than Hua’s rigid dedication to Mao.