Hugger-Mugger in the Giardini

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Jennifer Nicola Wilson, BA (Hons.)

EXHIBITING FRANCE IN AMERICA: THE FRENCH PAVILION AT THE NEW YORK WORLD’S FAIR OF 1939 by Jennifer Nicola Wilson, B.A. (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario June 16, 2006 © copyright 2006 Jennifer Wilson Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-18307-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-18307-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. -

8082 AUS VB07 ENG Edu Kit FA.Indd

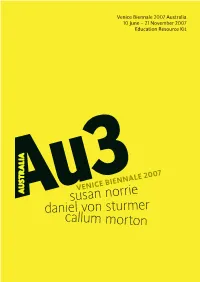

Venice Biennale 2007 Australia 10 June – 21 November 2007 Education Resource Kit Susan Norrie HAVOC 2007 Daniel von Sturmer The Object of Things 2007 Callum Morton Valhalla 2007 Contents Education resource kit outline Australians at the Venice Biennale Acknowledgements Why is the Venice Biennale important for Australian arts? Australia’s past participation in the Venice Biennale PART A The Venice Biennale and the Australian presentation Introduction Timeline: The Venice Biennale, a not so short history The Venice Biennale:La Biennale di Venezia Selected Resources Who what where when and why The Venice Biennale 2007 PART B Au3: 3 artists, 3 projects, 3 sites The exhibition Artists in profile National presentations Susan Norrie Collateral events Daniel von Sturmer Robert Storr, Director, Venice Biennale Callum Morton 2007 Map: Au3 Australian artists locations Curators statement: Thoughts on the at the Venice Biennale 2007 52nd International Art Exhibition Colour images Introducing the artist Au3: the Australian presentation 2007 Biography Foreword Representation Au3: 3 artists, 3 projects, 3 sites Collections Susan Norrie Quotes Daniel von Sturmer Commentary Callum Morton Years 9-12 Activities Other Participating Australian Artists Key words Rosemary Laing Shaun Gladwell Christian Capurro Curatorial Commentary: Au3 participating artists AU3 Venice Biennale 2007 Education Kit Australia Council for the Arts 3 Education Resource Kit outline This education resource kit highlights key artworks, ideas and themes of Au3: the 3 artists, their 3 projects which are presented for the first time at 3 different sites that make up the exhibition of Australian artists at the Venice Biennale 10 June to 21 November 2007. It aims to provide a entry point and context for using the Venice Biennale and the Au3 exhibition and artworks as a resource for Years 9-12 education audiences, studying Visual Arts within Australian High Schools. -

The Visitor As a Commercial Partner: Notes on the 58Th Venice Biennale

Daniel Birnbaum: Seventy-nine artists is a relatively limited number. Ralph Rugoff: How many did you have in yours? Daniel Birnbaum: I can’t remember. – Artforum, May 20191 01/09 The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise. Claire Fontaine – F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up, 1936 In his statement inaugurating the 58th Venice The Visitor as a Biennale, Paolo Baratta, its president, felt compelled to address the image of the event. Commercial Entitled “The Visitor as a Partner,” the statement Partner: Notes reads in part: A partial vision of the Exhibition might consider it a high-society inauguration on the 58th followed by a line six months long for “the rest of the world.” Others might consider Venice Biennale the six-month-long Exhibition the main event and the inauguration a by-product. It would be so useful if journalists would e l a come at another moment and not during n n e the “three-day event” of the “society” i B inauguration, which can only give them a e c i 2 n very partial image of the Biennale! e V e h n t i 8 a It would be useful, indeed, but it won’t happen. t 5 n e o ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊ“Our visitors have become our main h F t e n partner,” Baratta candidly adds (meaning r i o a s l “commercial partner”), to such an extent that e C t Ê o during the overcrowded opening days, many 9 N 1 : 0 r artworks were at risk of being damaged, and 2 e r n t e basic health and safety standards weren’t r b a m P followed. -

Constructing Buildings Or Places? May 26 – November 25, 2018

FRENCH PAVILION 16TH INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE EXHIBITION INFINITE DI VENEZIA LA LA BIENNALE PLACES CONSTRUCTING BUILDINGS OR PLACES? MAY 26 – NOVEMBER 25, 2018 L’HÔTEL PASTEUR (RENNES) LE CENTQUATRE (PARIS) LE TRI POSTAL (AVIGNON) LES GRANDS VOISINS (PARIS) LE 6B (SAINT-DENIS) LA CONVENTION (AUCH) LA FRICHE LA BELLE DE MAI (MARSEILLE) LES ATELIERS MÉDICIS (CLICHY-SOUS-BOIS-MONTFERMEIL) LA FERME DU BONHEUR (NANTERRE) LA GRANDE HALLE (COLOMBELLES) CURATORS: ENCORE HEUREUX NICOLA DELON — JULIEN CHOPPIN — SÉBASTIEN EYMARD AVEC COLLECTIF ETC – DEVALENCE – JOCHEN GERNER – RONAN LETOURNEUR – ALEXA BRUNET CYRILLE WEINER – MAKE IT – STRAAT – YES WE CAMP – BIENNALE URBANA INFINITE PLACES CONSTRUCTING BUILDINGS OR PLACES? french pavIlIon 16th InternatIonal archItecture exhIbItIon la bIennale dI venezIa curators: encore heureux press kIt Architecture not only has the capacity to give birth. It also has a capacity for rebirth. It helps us build, create, and construct. It also helps us reinvent: to give a new life to abandoned or neglected places, MINISTRY to transform, rehabilitate, and reconvert buildings, sites, or neighborhoods. In this 16th edition of the Internationale Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale OF di Venezia, the French Pavilion gives its place of honor to these innovative architectural projects, in the service of the city. The French submission, entitled Infinite Places, highlights ten exemplary projects, located in the four corners of France. I would like to thank and congratulate the Encore Heureux group, CULTURE the commissioners of this exhibition, for its magnificent work and its commitment to enhancing the reputation of our architects. The ten Infinite Places presented here consist of projects developed for abandoned buildings – from former office to former funeral homes – located in outlying districts. -

Jsc on View: Mythologists 17 January – 6 June 2021

JSC ON VIEW: MYTHOLOGISTS 17 JANUARY – 6 JUNE 2021 Wu Tsang, Wildness, 2012, HD video, 74′, color, sound. Video still. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin. The third edition of JSC ON VIEW, a series of exhibitions focusing explicitly on the inventory of works in the JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION, presents video and sound installations from twelve internationally renowned artists, some of whom are being exhibited at JSC Düsseldorf for the first time. JSC ON VIEW: MYTHOLOGISTS is curated by Rachel Vera Steinberg, fellow of the JSC Curatorial & Research Residency Program (CRRP) 2019–2020. Perceptions of truth are widely mediated through moving images. While they can be used by those in authority to exert influence, this exhibition explores the ways in which time-based media can Schanzenstrasse 54 T +49 211 585 884 0 [email protected] D 40549 Düsseldorf F +49 211 585 884 19 www.jsc.art connect political ideologies with the desire to create a world of one’s own. Borrowing from various cultural narratives, the works expound on their potential to serve as an incubator for social mythologies. Traditionally understood as narrations about gods, creation, and sanctity, myths are stories that are widely shared and factually ambiguous. They tell unverified truths, educate and entertain at the same time, and create archetypes from simple characters. JSC ON VIEW: MYTHOLOGISTS addresses the tensions created between facts and fictions through the production of personal as well as collective narratives. The works each grapple with various mythologies by reinterpreting histories, disrupting established behaviors, and imagining new visual and sonic worlds. -

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction ITALIAN MODERN ART - ISSUE 3 | INTRODUCTION italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/introduction-3 Raffaele Bedarida | Silvia Bignami | Davide Colombo Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020 https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of- exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/ ABSTRACT A brief overview of the third issue of Italian Modern Art dedicated to the MoMA 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, including a literature review, methodological framework, and acknowledgments. If the study of artistic exchange across national boundaries has grown exponentially over the past decade as art historians have interrogated historical patterns, cultural dynamics, and the historical consequences of globalization, within such study the exchange between Italy and the United States in the twentieth-century has emerged as an exemplary case.1 A major reason for this is the history of significant migration from the former to the latter, contributing to the establishment of transatlantic networks and avenues for cultural exchange. Waves of migration due to economic necessity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave way to the smaller in size but culturally impactful arrival in the U.S. of exiled Jews and political dissidents who left Fascist Italy during Benito Mussolini’s regime. In reverse, the presence in Italy of Americans – often participants in the Grand Tour or, in the 1950s, the so-called “Roman Holiday” phenomenon – helped to making Italian art, past and present, an important component in the formation of American artists and intellectuals.2 This history of exchange between Italy and the U.S. -

Type Title Author/Editor Publisher Date/Edition ISBN Category Book

Type TheTitle Autopoeisis of Architecture: A Author/Editor Publisher Date/Edition ISBN Category Book New Framework for Architecture, Vol. Patrik Schumacher Wiley 2011 9780470772980 Architectural Theory Book Labour,Critical Modernism Work, and Architecture: Charles Jencks Wiley 2007 0470030100 Architectural Theory Book TheorizingCollected Essays a New onAgenda Architecture for and Kenneth Frampton PrincetonPhaidon 2002 0714840807 Architectural Theory Book Architecture: An Anthology of MadelineKate Nesbitt, Gins Ed. and UniversityArchitectural of Press 1996 156898054X Architectural Theory Book MyArchitectural Works and Body Days: A Personal Arakawa Harcourt,Alabama PressBrace, 1979, 2002First 9780817311698 Architectural Theory Book FindingsChronicle and Keepings: Analects for Lewis Mumford Harcourt,Jovanovich Brace, 1975,Edition First 0151640874 Architectural Theory Book an autobiography Lewis Mumford TheJovanovich Monacelli Edition 0151309841 Architectural Theory Book Henry N. Cobb: Words & Works Eeva-LiisaHenry N. Cobb YalePress School of 2018 9781580935142 Architectural Theory Book Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox? Pelkonen with Architecture, Actar 2015 9781940291598 Architectural Theory Book NumberRethinking 9: TheHappiness Search for the Sigma Aldo Cibic Corraini Edizioni 2010 9788875702656 Architectural Theory Book ArchitectureCode Words 7: Modernity Cecil Balmond ArchitecturalPrestel 2008 9783791340678 Architectural Theory Book ArchitectureUnbound Words 12: Stones Detlef Mertins ArchitecturalAssociation 2011 9781902902890 Architectural -

Many National (Or Quasi-National) Entities Without a Physical Presence in the Giardini Have Been Temporarily Housed Within the A

(Review article) ‘57th Venice Biennale and Parallel Exhibitions’, MIRAJ 7:1, 2018, 176-185. Maeve Connolly This year’s international exhibition at the 57th Venice Biennale, curated by Christine Macel under the heading Viva Arte Viva, was organised as a series of nine themed pavilions, extending from the building now known as the Central Pavilion in the Giardini to the complex of structures and gardens that make up the Arsenale. Macel’s thematic framework was often startlingly literal in its conception and execution. So, for example, the ‘Pavilion of Artists and Books’ seemed to be composed largely of works featuring images of artists (or artists actually present in the exhibition) or made from books. This literalism continued almost unabated to the ends of the Arsenale, where several colourful installations were clustered together in the ‘Pavilion of Colours’. Instead of constituting a meaningful curatorial proposition, this year’s proliferation of pavilions tended to further muddle the already confused organisational and spatial boundaries between the national representations and international exhibition in the Arsenale.1 Within the Giardini itself, however, some national representations – notably the Dutch and Swiss – offered much richer responses to the pavilion, understood both as an architectural form and an ideal, offering new ways of understanding relationships between cinema, modernist architecture and ongoing processes of nation formation. Responding to this intersection of cinema and architecture, my review focuses on works that either involve the moving image or reference media histories and practices in other ways, spanning the international selection, national representations, official collateral programme and parallel exhibitions. Since at least the mid-2000s, artists and curators at the Biennale have drawn upon cinema and the architecture of the movie theatre to explore the formation and articulation of cultural and social identities. -

Journal on Biennials and Other Exhibitions Why Venice?

Journal On Biennials Why Venice? Vol. I, No. 1 (2020) and Other Exhibitions Martina Tanga Flipping the Exhibition Inside Out: Enrico Crispolti’s Show Ambiente come Sociale at the 1976 Venice Biennale Abstract In 1976, art historian and curator Enrico Crispolti – charged with organizing the show, Ambiente come Sociale, for the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale – rad- ically rethought the exhibition form. In an unconventional move, he strategically chose not to house any artworks within the confines of the gallery space. Instead, he sprawled documentary photographs, videos, texts, pamphlets, and audio record- ings on tables like the products of field research. The artworks themselves were site-specific and located elsewhere in various towns and cities across the country. Adhering to the Biennale’s overarching theme of environment and decentralization, Crispolti championed artists working in Arte Ambientale (environmental art), who were making art located in the urban context and social reality. Yet, Crispolti turned the institution’s theme inside out: while visitors came to its center to see the art, they were thrust outwards towards the peripheries, and outside in the city, where the actual artworks were sited. The ingenuity of this action, and the re-conception of what could constitute installation art, is evident when Crispolti’s exhibition is compared to Germano Celant’s 1976 Biennale show Ambiente/Arte, a diachronic art historical study of this new art medium. While Celant presented self-referential examples based on formal qualities, Crispolti exponentially broad- ened the boundaries of installation art to include the environment, urban context, social questions, and political contingency. -

In the Art World

M Elisabeth de Brabant, founding director of Elisabeth de Brabant Contemporary Fine Art, Shanghai - Paris - Hong Kong. (See interview in this issue) in the art world the M magazine theMmag.com Summer 2009 Marco Breuer, Early Light/Sylvania AG/1B (C-819), 2008, chromogenic paper, exposed, 14 x 10 15/16 inches, unique YORK VONLINTEL.COM VONLINTEL.COM YORK NEW RECEPTION: THURSDAY, MAY 7, 6–8 PM MAY RECEPTION: THURSDAY, STREET NEW YORK, NY 10011 TEL 1 212 242 0599 FAX 1 347 464 0011 [email protected] NY 10011 TEL 1 212 242 0599 FAX STREET NEW YORK, RD LINTEL GALLERY LINTEL GALLERY 23 WEST VON 520 MARCO BREUER PART __ OF __ PARTS OF __ __ PART 7–JUNE 13, 2009 MAY OPENING YORK VONLINTEL.COM VONLINTEL.COM YORK NEW YORK, NY 10011 TEL 1 212 242 0599 FAX 1 347 464 0011 [email protected] NY 10011 TEL 1 212 242 0599 FAX YORK, GALLERY GALLERY 10011 STREET NEW RD NY 23 FLOOR STREET RD LINTEL 23 LOCATION YORK, WEST WEST VON 520 520 NEW NEW Izima Kaoru, Sakai Maki wears Jil Sander (502), 2008, C-print, 70.9 x 59 inches GROUND he past is a foreign country; they do things differently Tthere — Leslie Poles Hartley. Actually I never read the th eMmag.com novel this prescient quote is attributed to, The Go-Between (1953). But with the recent death of Harold Pinter, who wrote the screenplay for the 1971 film adaptation, I’ve EDITORIAL been sifting through fragments of language that resonate across time. Seems like a lot of people want to go back in time. -

The Georgian

J X £ ‘<14 ■ - A - ^ • J? ■a? J <ar I os * 4 * A ’ t i * £ -A: ■ .* « ? ^ .^s•' ,£\Vk,/% ‘ / A S T ^ < -%>ys+f ■ .,£*•* ( - . > / w r • j t * I £ f . vs^ the georgian Sir George Williams University Any event with the scope of the 1967 Man and His World Expo jo b s? To stimulate the intelligence and ingenuity of participants and Expo’s employment opportuni ration “intends to make every World Exposition in prospective visitors alike, world exhibitions usually have a central ties will offer students an ef human effort possible to hire unifying theme. Expo 67’s theme, ‘'Man and His World”, was inspired fective and interesting means of university students.” This point Montreal can be only by the title of the book “Terre des Hommes” (published in English participation. It has been estim was emphasized in view of the as “Wind, Sand and Stars”) by the French author, poet and aviator, ated that 3,000 new employees problems that arise : hiring dates Antoine de Saint-Exupery. The underlying philosophy of this work, will be needed, 650 of which (April 17-21) and training pe as good as its organ and of Expo’s theme, is sununcd up in a passage in which Saint- could be students. Concessionai riods will fall before the end of Exupery wrote : res will need approximately 2,300 the academic year, and students izers and executive... "To be a man... is to feel that through one's own people for restaurants, boutiques, will have to return to lectures contribution one helps to build the world." etc., and exhibitors might hire before the end of the Exhibition. -

Untitled (Dirt), As Well As Documentary Photographs of Artworks Sited Elsewhere

Journal On Biennials and Other Exhibitions Director Angela Vettese, Università Iuav di Venezia Editors Clarissa Ricci, Università di Bologna Camilla Salvaneschi, Università Iuav di Venezia / University of Aberdeen Editorial Board Marco Bertozzi, Università Iuav di Venezia Renato Bocchi, Università Iuav di Venezia Amy Bryzgel, University of Aberdeen Silvia Casini, University of Aberdeen Agostino De Rosa, Università Iuav di Venezia Paolo Garbolino, Università Iuav di Venezia Chiara Vecchiarelli, Università Iuav di Venezia / École Normale Supérieure, Paris International Advisory Board Bruce Altshuler, New York University Dora Garcia, Kunsthøgskolen i Oslo (Oslo National Academy of the Arts) Anthony Gardner, Ruskin School of Art University of Oxford Charles Green, University of Melbourne Marieke Van Hal, Manifesta Foundation Amsterdam Joan Jonas, MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology Caroline A. Jones, MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology Antoni Muntadas, MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology Mark Nash, Birkbeck University of London Rafal Niemojewski, Biennial Foundation New York Terry Smith, University of Pittsburg Benjamin Weil, Centro Botin Santander Proofreaders Max Fletcher Chris Heppell Publisher OBOE On Biennials and Other Exhibitions Associazione Culturale, Venice Co-publisher Università Iuav di Venezia, Venice Graphic Design Zaven, Venice Acknowledgements OBOE Journal wishes to thank the many individuals that have contributed to its publication. These include the board members, trustees and partners, the University,