The Second Coming of Steven Cohen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fund Writing Loans Against Crypto Portfolios Market Trends Seen Culling Long/Short Herd Ex-Two Sigma Pro Markets Lockup Vehicle

JANUARY 10, 2018 Fund Writing Loans Against Crypto Portfolios A Denver startup has launched a first-of-its kind hedge fund that seeks returns 3 BIGGEST LAUNCHES OF 2017 from writing loans secured by cryptocurrencies. SALT Lending began originations through its Crypto Credit Opportunity Fund on 2 Minnesota Startup Mines Local Talent Dec. 27. It also operates a marketplace-lending platform to match individuals and 2 Buyer Emerges for Citco Stake businesses that wish to borrow dollars against their holdings of digital currencies with institutional lenders, including SALT’s hedge fund. 2 Ex-SAC Staffer Preps Quant Fund In marketing the fund, SALT is highlighting the opportunity for investors to gain exposure to a rapidly emerging asset class without the operational headaches of 4 Suit Casts Doubt on SkyBridge Deal owning digital currencies directly. The firm also emphasizes the potential to reap 4 BNP Takes New Approach to Cap Intro high-yield returns on secured debt at a time when interest rates continue to hover near historic lows. 6 Year-Ago Consensus Too Cautious Still, SALT faces the difficult task of winning over investors who might be put off by See CRYPTO on Page 5 7 Gauging the Lure of Crypto Returns 8 New Path for Industrial-Stock Pro Market Trends Seen Culling Long/Short Herd 8 Crypto Fund Tally Still Growing The field of long/short equity funds — the oldest and still-largest category of 8 INFLOWS/OUTFLOWS BY STRATEGY hedge funds — is poised to contract by as much as a third due to ongoing structural changes in the stock market. -

Steven Cohen's Point72 Is Accused of Sexism in Workplace

Steven Cohen's Point72 Is Accused of Sexism in Workplace www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-13/steve-cohen-s-point72-accused-in-lawsuit-of-sexism-in-workplace Just as billionaire Steven Cohen stages a comeback as a hedge fund manager, a current employee sued his Point72 Asset Management accusing it of discriminating against women and promoting a culture of sexism. Lauren Bonner, an associate director at the firm, also accused President Doug Haynes of using an inappropriate term on a white board in his office and leaving it there for weeks, according to the complaint filed in federal court in New York on Monday. Haynes, a former McKinsey & Co. director, was hired in 2014 and led efforts to revamp Cohen’s business after it pleaded guilty to securities fraud and paid a record fine. Bonner, who joined Point72 in August 2016, runs the firm’s talent analytics team and manages 14 people, according to the complaint. She alleges the firm hired and promoted fewer women than men, paid her less than male counterparts with equal or fewer responsibilities and had only one woman portfolio manager and only one female managing director. Point72 “emphatically denies these allegations and will defend itself in a more appropriate venue than the media,” the Stamford, Connecticut-based firm said in an emailed statement. ‘Vital Members’ “We stand by our record of hiring and developing women,” the firm said. “In an industry where women are historically underrepresented, the hundreds of women at Point72 are vital members of every part of our organization. Our female investment professional workforce exceeds published industry averages -- a direct result of our concerted and sustained focus on promoting diversity at Point72.” Bonner’s attorneys at Wigdor LLP said in an emailed statement that the lawsuit “exposes the structural sexism at Point72.” Along with Point72, Cohen and Haynes are named as defendants in the case. -

The Quants Run Wall Street Now - WSJ 5/24/17, 11:08 AM

The QuantsTHE Run Wall Street Now - WSJ QUANTS RUN5/24/17, 11:08 AM WALL STREET SHARE NOW For decades, investors imagined a time when data-driven traders would dominate financial markets. That day has arrived. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-quants-run-wall-street-now-1495389108 Page 1 of 14 The Quants Run Wall Street Now - WSJ 5/24/17, 11:08 AM BY GREGORY ZUCKERMAN AND BRADLEY HOPE Alexey Poyarkov, a former gold-medal winner of the International Mathematical Olympiad for high-school students, spent most of his early career honing algorithms ? at technology companies such as Microsoft Corp. , where he helped make the Bing search engine smarter at ferreting out pornography. Last year, a bidding war for Mr. Poyarkov broke out among hedge-fund heavyweights Renaissance Technologies LLC, Citadel LLC and TGS Management Co. When it was over, he went to work at TGS in Irvine, Calif., and could earn as much as $700,000 in his first year, say people familiar with the contract. The Russian-born software engineer, who declined to comment, as did the hedge funds, had almost no financial experience. What TGS wanted was his wizardry at designing algorithms, sets of rules used to power calculations and problem- solving, which in the investment world can quickly parse data and decide what to buy and sell, often with little human involvement. Up and down Wall Street, algorithmic-driven trading WSJ PODCAST and the quants who use sophisticated statistical models to find attractive trades are taking over the The Quants: Today’s Kings investment world. -

Ex-Commonwealth PM Set to Launch $500M Macro Fund LAUNCH

The long and the short of it www.hfmweek.com ISSUE 497 3 MAY 2018 INFRAHEDGE CEO BRUCE KEITH DEPARTS AFTER 7 YEARS HFM EUROPEAN 2018 $30bn MAP co-founder to be replaced by Andrew Allright PEOPLE MOVES 03 PERFORMANCE AWARDS DEUTSCHE PUTS PRIME FINANCE BUSINESS UNDER REVIEW HF head Tarun Nagpal to leave bank after 15 years PRIME BROKERAGE 07 EX-GRUSS CAPITAL PROS PREP EVENT-DRIVEN FUND HFMWEEK REVEALS ALL Indar Capital expected to launch later this year LAUNCHES 10 THE WINNERS AWARDS 23 Ex-CommonWealth PM set to launch $500m macro fund Christopher Wheeler readies between 2013 and 2016. London-based CJW Capital CommonWealth closed BY SAM MACDONALD down last year as Fisher depart- ed to join $26bn Soros Fund FORMER CITADEL AND Management. CommonWealth Opportunity From November 2016 until Capital portfolio manager Chris- March this year, Wheeler is topher Wheeler is set to launch a understood to have traded a sub- LAUNCH macro fund with at least $500m stantial macro sleeve for Citadel. initial investment, HFMWeek He previously spent five years has learned. with London-based liquid multi- ANALYSIS Wheeler is starting London- asset business Talisman Global NUMBERS SURGE IN 2017 based CJW Capital Management Asset Management. He earlier with backing from a large asset worked at Morgan Stanley. manager and is looking to begin CJW Capital could become trading this year, HFMWeek one of this year’s largest HFM Global’s annual survey shows understands. European start-ups, amid a num- He registered the firm with ber of prominent macro hedge equity strategies remained most in UK Companies House on 23 fund launches. -

Bi-Weekly Finanial Technology Sector Report

Financial Technology Sector Summary Week of May 8, 2017 1 DEAL DASHBOARD Financial Technology (3) (1) (3) $11.7 Bn | 1,179 Deals Industry Stock Market Performance $347.2 Bn | 3,159 Deals LTM Financing Volume Last Twelve Months LTM M&A Volume 160 Select Recent Financing Transactions Select Recent M&A Transactions Company Amount ($MM) 150 Target Acquirer EV ($MM) 140 $110.0 $675.0 130 $70.0 $30.0 120 $56.0 110 NA 100 $54.0 NA 90 $50.0 NA 80 5/5/16 6/20/16 8/3/16 9/16/16 11/1/16 12/15/16 1/30/17 3/15/17 4/28/17 $32.0 NA Aicai Payments Exchanges Financial Data, Content, Information Processors / $17.5 & Analytics Credit Bureaus NA Banking & Lending Online Broker Dealers Technology $15.7 NA Investment Services, Healthcare / Insurance Software, & Technology Technology S&P 500 (3) (3) Quarterly Financing Volume Quarterly M&A Volume $10 500 $120 876 1000 818 783 750 $8 $8.9 400 $100 800 $99.4 299 298 316 $97.8 276 $80 $6 300 $83.1 $81.6 600 $60 $4 200 400 $40 $3.0 $2 $2.6 $2.6 100 $20 200 $0 0 $0 0 Q2 2016 Q3 2016 Q4 2016 Q1 2017 Q2 2016 Q3 2016 Q4 2016 Q1 2017 Financing Volume ($Bn) Financing Deal Count M&A Volume ($Bn) M&A Deal Count Notes: Source: Capital IQ, CB Insights and GCA FinTech Database. Market Data as of 5/5/17. 1) Refer to footnotes on page 5 for index composition. -

Steven Cohen's Investment Firm Accused of Hostility to Women

Steven Cohen’s Investment Firm Accused of Hostility to Women nytimes.com/2018/02/12/business/steven-cohen-point72-discrimination-lauren-bonner.html A female executive at the investment firm run by Steven A. Cohen, the billionaire investor, said in a lawsuit that the company was a testosterone-fueled “boys’ club” in which men commented on women’s bodies, belittled their abilities and paid them less than their male peers. The lawsuit, filed in federal court Monday by a current employee of Mr. Cohen’s Point72 Asset Management, describes a toxic working environment for women. Those with years of experience were often referred to as “girls” or “sweethearts.” Some were excluded from meetings that were deemed for men only, the lawsuit said. The lawsuit offers a rare glimpse inside the $11 billion firm, which is run by one of Wall Street’s most fabled traders and is a huge source of business across the banking industry. Mr. Cohen, who is in the midst of trying to repair his tarnished public image and raise money from investors, is not accused of inappropriate behavior in the lawsuit. In a statement on Monday, Point72 said, “The firm emphatically denies these allegations and will defend itself in a more appropriate venue than the media.” It added: “We stand by our record of hiring and developing women. In an industry where women are historically underrepresented, the hundreds of women at Point72 are vital members of every part of our organization.” Mr. Cohen’s former firm, SAC Capital Advisors, shut down in early 2014 after it pleaded guilty in an insider trading investigation. -

Point72 Employee Investment Fund, LP Form 40-6B

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 40-6B/A Application for exemption from all provisions of The Investment Company Act of 1940 by an Employee's Investment Company [amend] Filing Date: 2021-06-16 SEC Accession No. 0000895345-21-000552 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Point72 Employee Investment Fund, L.P. Mailing Address Business Address 72 CUMMINGS POINT ROAD 72 CUMMINGS POINT ROAD CIK:1753770| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 STAMFORD CT 06902 STAMFORD CT 06902 Type: 40-6B/A | Act: 40 | File No.: 813-00393 | Film No.: 211020154 203-890-2000 Point72 Asset Management, L.P. Mailing Address Business Address 72 CUMMINGS POINT ROAD 72 CUMMINGS POINT ROAD CIK:1603466| IRS No.: 465064661 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 STAMFORD CT 06902 STAMFORD CT 06902 Type: 40-6B/A | Act: 40 | File No.: 813-00393-01 | Film No.: 211020155 203-890-2000 Copyright © 2021 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Point72 Employee Investment Fund, L.P. Point72 Asset Management, L.P. (Names of Applicants) 72 Cummings Point Road Stamford, Connecticut 06902-7912 (Address of principal offices of Applicants) AMENDMENT NO. 2 TO APPLICATION PURSUANT TO SECTIONS 6(b) AND 6(e) OF THE INVESTMENT COMPANY ACT OF 1940 FOR AN ORDER EXEMPTING APPLICANTS FROM CERTAIN PROVISIONS OF THAT ACT Written communications regarding this Application and copies of all orders should be addressed to the following persons: Vincent Tortorella Jason Colombo Point72 Asset Management, L.P. -

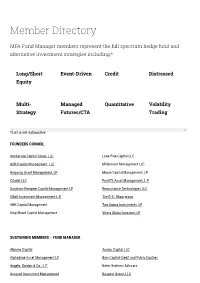

Member Directory

Member Directory MFA Fund Manager members represent the full spectrum hedge fund and alternative investment strategies including:* Long/Short Event-Driven Credit Distressed Equity Multi- Managed Quantitative Volatility Strategy Futures/CTA Trading *List is not exhaustive FOUNDERS COUNCIL Anchorage Capital Group, LLC Lone Pine Capital LLC AQR Capital Management, LLC Millennium Management LLC Balyasny Asset Management, LP Moore Capital Management, LP Citadel LLC Point72 Asset Management, L.P. Davidson Kempner Capital Management LP Renaissance Technologies LLC Elliott Investment Management L.P. The D. E. Shaw group HBK Capital Management Two Sigma Investments, LP King Street Capital Management Viking Global Investors LP SUSTAINING MEMBERS – FUND MANAGER Abrams Capital Axonic Capital LLC Alphadyne Asset Management LP Bain Capital Credit and Public Equities Angelo, Gordon & Co., L.P. Baker Brothers Advisors Assured Investment Management Baupost Group, LLC BlackRock Alternative Investors IONIC Capital Management LLC Bracebridge Capital, LLC Junto Capital Management LP Bridgewater Associates, LP. Kensico Capital Management Brigade Capital Management, LP Kepos Capital LP Cadian Capital Management Kingdon Capital Management, LLC Campbell & Company, LP Laurion Capital Management LP Capula Investment Management LLP Magnetar Capital LLC CarVal Investors Man Group Casdin Capital Marathon Asset Management, L.P. Castle Hook Partners LP Marshall Wace North America LP Centerbridge Partners, L.P. Melvin Capital CIFC Asset Management Meritage Group LP Coatue Management LLC Millburn Ridgeeld Corporation D1 Capital Partners MKP Capital Management Diameter Capital Partners LP Monarch Alternative Capital LP EJF Capital, LLC Napier Park Global Capital Element Capital Management LLC One William Street Capital Management LP Eminence Capital, LP P. Schoenfeld Asset Management LP Empyrean Capital Partners, LP Palestra Capital Management LLC Emso Asset Management Limited Paloma Partners Management Company ExodusPoint Capital Management, LP PAR Capital Management, Inc. -

A Tug of War: Overnight Versus Intraday Expected Returns

A Tug of War: Overnight Versus Intraday Expected Returns Dong Lou, Christopher Polk, and Spyros Skouras1 First draft: August 2014 This version: January 2016 1 Lou: Department of Finance, London School of Economics, London WC2A 2AE, UK and CEPR. Email [email protected]. Polk: Department of Finance, London School of Economics, London WC2A 2AE, UK and CEPR. Email [email protected]. Skouras: Athens University of Economics and Business. Email sk- [email protected]. We are grateful to John Campbell, Randy Cohen, Josh Coval, Roger Edelen, Andrea Frazzini, Narasimhan Jegadeesh, Marcin Kacperczyk, Toby Moskowitz, Paul Tetlock, Sheridan Titman, Dimitri Vayanos, Tuomo Vuolteenaho and seminar participants at Duisenberg School of Finance and Tin- bergen Institute, Hong Kong University, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, IDC Herzliya, IESE Business School, Imperial College, London Business School, London School of Economics, Luxembourg School of Finance, University of Bristol, University of Minho, University of Minnesota, University of South- ern California, University of Zurich, 2015 Adam Smith Asset Pricing Conference, 2015 Crete Conference on Research on Economic Theory and Econometrics, 2014 Financial Research Association conference, 2015 NBER Behavioral Finance Meeting, 2015 NBER Asset Pricing Meeting, 2015 Western Finance Association Annual Meeting, ArrowStreet Capital, and Point72 Asset Management for helpful comments. We thank Andrea Frazzini, Ken French, and Sophia Li for providing data used in the analysis as well as Huaizhi Chen and Michela Verardo for assistance with TAQ. Financial support from the Paul Woolley Centre at the LSE is gratefully acknowledged. A Tug of War: Overnight Versus Intraday Expected Returns Abstract We show that momentum profits accrue entirely overnight while profits on all other trad- ing strategies studied occur entirely intraday. -

GREEN’ SCREENS Industry Seeks ESG Standards to Support Demand for Responsible Investments

Dealmakers Give the Lowdown On the State of Play in M&A QUANTS STRUGGLE TO DERIVE VALUE FROM ALT DATA More Exchanges Eye ‘Flash Boys’ Speed Bumps ‘GREEN’ SCREENS Industry Seeks ESG Standards to Support Demand for Responsible Investments waterstechnology.com May 2017 smartstreamrdu.com Simplifying Reference Data. Together. Established as an industry utility based on the principle of market commonality, collaboration and contribution, The SmartStream Reference Data Utility (RDU) delivers a cost efficient approach to realize the truth of the data contained within the industry with guaranteed results. Managing data holistically across legal entity, instrument and corporate action data, this shared service model promotes fixes to data processing across the instrument lifecycle and the events that originate and change data. Join the revolution, contact us today: [email protected] Editor Max Bowie Tel: +1 646 490 3966 [email protected] European Reporter Joanne Faulkner Tel: +44 (0) 20 7316 9338 [email protected] Asia Staff Reporter Wei-Shen Wong Tel: +852 3411 4758 [email protected] Publisher Katie Palisoul Tel: +44 (0)20 7316 9782 [email protected] Global Commercial Director Colin Minnihan Tel: +1 646 755 7253 [email protected] Business Development Executive Michael Balzano Tel: +1 646 755 7255 [email protected] Business Development Executive Christopher Fiume Tel: +1 646 736 1887 christopher.fi [email protected] Business Development Executive Tom Riley Don’t Put All ESGs in One Basket Tel: +44 (0) 20 7316 9780 [email protected] Group Publishing Director Lee Hartt Head of Editorial Operations Elina Patler millennials: their birds-nest Commercial Editorial Manager Stuart Willes We love to hate beards, skinny jeans, and Senior Marketing Executive Louise Sheppey snobby cocktails. -

When a Stock “Goes Viral”

February 12, 2021 When a Stock “Goes Viral” View as PDF “You don’t see revolutions happening, they just occur, and I think we’re in a moment like that in financial history. The hard thing to measure is how much buying power is in these bulletin boards.” – Bob Sloan, Founder of S3 Partners ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ DISCLOSURE: Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. When a Stock “Goes Viral” YouTube, the popular online video-sharing company now owned by Alphabet Inc. (more commonly referred to as Google), was founded in the wake of the dotcom bubble in 2005. The company was a true trailblazer at the time, enabling content creators to host their work on a cloud-based platform that was instantly accessible to millions of subscribers around the world. The early success of YouTube as a go-to content platform eventually spawned the term “viral video,” which refers to a video that is viewed, shared, and reshared millions – if not billions – of times around the world. The term “going viral” is particularly popular among Millennials and Gen Zers, who came of age in a time where any piece of content could instantly turn someone from obscurity into a star, or from a star into a superstar. There are so many examples of this phenomenon over the past decade-and-a-half that some people have even built entire careers on the ability to take someone or something “viral” on the internet. -

Point72 Employee Investment Fund, L.P. and Point72 Asset Management, L.P

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Investment Company Act Release No. 34365; 813-00393 Point72 Employee Investment Fund, L.P. and Point72 Asset Management, L.P. August 26, 2021 AGENCY: Securities and Exchange Commission (“Commission”). ACTION: Notice. Notice of application for an order under sections 6(b) and 6(e) of the Investment Company Act of 1940 (the “Act”) granting an exemption from all provisions of the Act and the rules and regulations thereunder, except sections 9, 17, 30, and 36 through 53 of the Act, and the rules and regulations thereunder (the “Rules and Regulations”). With respect to sections 17(a), (d), (e), (f), (g) and (j) and 30(a), (b), (e), and (h) of the Act, and the Rules and Regulations, and rule 38a-1 under the Act, the exemption is limited as set forth in the application. Summary of Application: Applicants request an order to exempt certain limited partnerships, limited liability companies, business trusts or other entities (“Funds”) formed for the benefit of eligible employees of Point72 Asset Management, L.P. (“Point72”) and its affiliates from certain provisions of the Act. Each series of a Fund will be an “employees’ securities company” within the meaning of section 2(a)(13) of the Act. Applicants: Point72 Employee Investment Fund, L.P. and Point72 Asset Management, L.P. Filing Dates: The application was filed on September 28, 2018 and amended on July 21, 2020, and June 16, 2021. Hearing or Notification of Hearing: An order granting the requested relief will be issued unless the Commission orders a hearing. Interested persons may request a hearing by e-mailing the Commission’s Secretary at [email protected] and serving applicants with a copy of 1 the request by e-mail.