Guidelines for the Administration of Platelets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Transfusions

Guidelines for Transfu- sion Prepared by: Community Transfusion Committee Lincoln, Nebraska CHAIR: Aina Silenieks, MD MEMBERS: L. Bausch, M.D. R. Burton, M.D. S. Dunder, M.D. D. Voigt, M.D. B. J. Wilson, M.D. COMMUNITY Becky Croner REPRESENTATIVES: Ellen DiSalvo Christa Engel Phyllis Ericson Kelly Gillaspie Pat Gilles Vic Grdina Jessica Henrichs Kelly Jensen Laurel McReynolds Christina Nickel Angela Novotny Kelley Thiemann Janet Wachter Jodi Wikoff Guidelines For Transfusion Community Transfusion Committee INTRODUCTION The Community Transfusion Committee is a multidisciplinary group that meets to monitor blood utilization practices, establish guidelines for transfusion and discuss relevant transfusion related topics. It is comprised of physicians from local hospitals, invited guests, and community representatives from the hospitals’ transfusion services, nursing services, perfusion services, health information management, and the Nebraska Community Blood Bank. These Guidelines for Transfusion are reviewed and revised biannually by the Community Trans- fusion Committee to ensure that the industry’s most current practices are promoted. The Guidelines are the standard by which utilization practices are evaluated. They are also de- signed to provide helpful information to assist physicians to provide appropriate blood compo- nent therapy to patients. Appendices have been added for informational purposes and are not to be used as guidance for clinical decision making. ADULT RED CELLS A. Indications 1. One of the following a. Hypovolemia and hypoxia (signs/symptoms: syncope, dyspnea, postural hypoten- sion, tachycardia, angina, or TIA) secondary to surgery, trauma, GI tract bleeding, or intravascular hemolysis, OR b. Evidence of acute loss of 15% of total blood volume or >750 mL blood loss, OR c. -

27. Clinical Indications for Cryoprecipitate And

27. CLINICAL INDICATIONS FOR CRYOPRECIPITATE AND FIBRINOGEN CONCENTRATE Cryoprecipitate is indicated in the treatment of fibrinogen deficiency or dysfibrinogenaemia.1 Fibrinogen concentrate is licenced for the treatment of acute bleeding episodes in patients with congenital fibrinogen deficiency, including afibrinogenaemia and hypofibrinogenaemia,2 and is currently funded under the National Blood Agreement. Key messages y Fibrinogen is an essential component of the coagulation system, due to its role in initial platelet aggregation and formation of a stable fibrin clot.3 y The decision to transfuse cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate to an individual patient should take into account the relative risks and benefits.3 y The routine use of cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate is not advised in medical or critically ill patients.2,4 y Cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate may be indicated in critical bleeding if fibrinogen levels are not maintained using FFP. In the setting of major obstetric haemorrhage, early administration of cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate may be necessary.3 Clinical implications y The routine use of cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate in medical or critically ill patients with coagulopathy is not advised. The underlying causes of coagulopathy should be identified; where transfusion is considered necessary, the risks and benefits should be considered for each patient. Specialist opinion is advised for the management of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (MED-PP18, CC-PP7).2,4 y Cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate may be indicated in critical bleeding if fibrinogen levels are not maintained using FFP. In patients with critical bleeding requiring massive transfusion, suggested doses of blood components is 3-4g (CBMT-PP10)3 in adults or as per the local Massive Transfusion Protocol. -

Transfusion Service Introduction Blood/Blood Products Requests and Turnaround Time Expectations

Transfusion Service Introduction All blood products and blood components are supplied to UnityPoint Health-Meriter Hospital by the American Red Cross Blood Services. Pathology consultation is available regarding blood and/or components and dosages. ABO and Rho(D)—specific type is used whenever possible for leuko-poor packed cell transfusions. ABO-compatible blood is used for all plasma and platelet components whenever possible. For any orders involving HLA-matched components, the patient must have been HLA typed (sent to the American Red Cross) a minimum of 48 hours prior to intended infusion of the component. HLA typing is only required once. Blood components that are thawed, pooled, washed, volume-reduced, or deglycerolized for a patient will be charged to the patient even if not transfused. The charge is done because these components may not be suitable for another patient. Examples include: Autologous or directed donations Pooled cryoprecipitate 4-hour expiration Thawed fresh frozen plasma 24-hour expiration Thawed cryoprecipitate 6-hour expiration Deglycerolized red cells 24-hour expiration Washed red cells 24-hour expiration All blood components must be completely infused within 4 hours of release from UnityPoint Health-Meriter Laboratories Blood Bank, or be infused within the expiration time. Refer to UnityPoint Health -Meriter’s Blood and Blood Products Transfusion Policy #123 for additional information located on MyMeriter. Blood/Blood Products Requests and Turnaround Time Expectations Requests from UnityPoint Health-Meriter Hospital are entered in the hospital computer system and print in the UnityPoint Health- Meriter Laboratories Blood Bank. For the comfort of the patient, it is important to coordinate collection for other tests with Blood Bank specimens. -

Donor-Alloantigen-Reactive Regulatory T Cell Therapy in Liver

Confidential Page 1 of 80 Donor-Alloantigen-Reactive Regulatory T Cell Therapy in Liver Transplantation Version 7.0/ August 1, 2018 IND# 15479 Study Sponsor(s): The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Grant #: R34AI095135 and U01AI110658-01 Study Drug Manufacturer/Provider: Sanofi US PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR CO- PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR CO- PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR SANDY FENG, MD, PHD JEFFREY BLUESTONE, PHD SANG-MO KANG, MD, FACS Professor of Surgery Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Associate Professor Director, Abdominal Transplant A.W. Clausen Distinguished Professor University of California, San Surgery Fellowship in Medicine Francisco University of California, San University of California, San Francisco 513 Parnassus Ave. Francisco 513 Parnassus Ave. Box 0780, HSE-520 505 Parnassus Ave. Box 0400, HSW-1128 San Francisco, CA 94143-0780 Box 0780, M-896 San Francisco, CA 94143-0780 Phone: (415) 353-1888 San Francisco, CA 94143-0780 Phone: (415) 476-4451 E-mail: Sang- Phone: (415) 353-8725 Fax: (415) 476-9634 [email protected] Fax: (415) 353-8709 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] CO- PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR BIOSTATISTICIAN MEDICAL OFFICER QIZHI TANG, PHD DAVID IKLÉ, PHD NANCY BRIDGES, MD Associate Professor Senior Statistical Scientist Chief, Transplantation Branch Director, UCSF Transplantation Rho, Inc. Division of Allergy, Immunology, Research Lab 6330 Quadrangle Drive and Transplantation University of California, San Chapel Hill, NC 27517 NIAID Francisco Phone: (910) 558-6678 -

Java Based Distributed Learning Platform

Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 8 (2020) 110-123 doi: 10.17265/2328-2150/2020.04.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Blood Group Cartography (ABO, RHESUS, KELL and DUFFY) and Hemogram of Icteric Newborn in Sendwe Hospital, Lubumbashi/D.R.C Monga Kalenga J. J1, Monga Ngoy Davidson2, Matanda Kapend Serge3, Masendu Kalenga Paulin4, Haumont Dominique5 and Luboya Numbi Oscar1 1. Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lubumbashi, Haut-Katanga 1825, DRC. 2. Laboratory Department Head Sendwe Hospital, Haut Katanga, Lubumbashi 1825, DRC 3. Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lubumbashi, Haut-Katanga 1825, DRC. 4. CHR The Citadel, Neonatology Department, University of Liège, Liège 4450, Belgium. 5. Free University of Brussels, Brussels 1050, Belgium Abstract: Background: Allo immunization jaundice is a common cause of neonatal jaundice. According to racial group the concerned blood group may not be the same. In our Country people are exposed to high transfusionnal risk because of malaria and sicklanemia and the blood group research in laboratory include only ABO/D. Objective: Our objective was to establish a blood group cartography of this icteric newborn population and their mother; the frequency of rare blood group and the compatibility level between mother and newborn. Our interest was also to study hemogram of this population. Methodology: We studied blood group ABO/D; RH/Kell and Duffy of 56 newborn whom developped an indirect bilirubin and their mothers. We performed bilrubin level and hemogram. Results: The frequency of icteric newborn was 17.17%. The mother blood mapping was O (60.71%), RhD positive (83.9%), C negative (91.07%) E negative (89.29%) c positive (91.07%), epositive (92.86%), kell negative (100%) and duffy null (100%). -

Humoral Alloimmunity in Cardiac Allograft Rejection

Humoral alloimmunity in cardiac allograft rejection Jawaher Alsughayyir Darwin College Department of Surgery University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2018 i Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where declared in the text. It has not been submitted in whole or part for a degree at any university. The length of this thesis does not exceed the 60,000 word limit i Dissertation title: Humoral alloimmunity in cardiac allograft rejection Student name: Jawaher Alsughayyir Abstract Although the short-term outcomes of solid allograft survival have improved substantially over the last few decades, there has been no significant improvement in long-term survival of solid allografts. This thesis presents the initial characterisation of alloantibody mediated rejection in a murine heart transplant model, with particular focus on the impact of the different phases of the humoral alloimmune response (follicular or germinal centre) on graft rejection. The key findings of this work are: 1) The precursor frequency of allospecific CD4 T cells determines the magnitude of the alloantibody response, with a relatively high frequency of CD4 T cells eliciting strong extrafollicular responses, while a high frequency of B cells promotes slowly-developing germinal centre responses. 2) Strong extrafollicular antibody response can mediate acute heart allograft rejection in the absence of CD8 T cells alloresponses. 3) Germinal centre humoral immunity mediates chronic antibody-mediated rejection. 4) Recipient memory, but not naïve, CD4 T cells that recognise one graft alloantigen can provide ‘unlinked’ help to allospecific B cells that recognise a different graft alloantigen for generating germinal centre alloantibody responses. -

Fresh Frozen Plasma in General Practice

Practical guide to using frozen and fresh frozen plasma in general practice Why every practice should keep a bag in the freezer Kit Sturgess; MA; VetMB; PhD; CertVR; DSAM; CertVC; FRCVS RCVS Recognised Specialist in Small Animal Medicine Advanced Practitioner in Veterinary Cardiology Introduction Keeping stock at reasonable levels in a practice is vital to good business management balancing the need to have a product available against the costs of keeping stock that is not used and potentially may go out of date and need to be replaced (as well as subtle small costs of space, stock taking, disposal of out-of-date product etc.). Practices need, therefore, to make decisions about preparedness for ‘what if’ scenarios and have protocols in place. The difficult question for many practices is how bizarre/uncommon should these scenarios be to warrant keeping a drug or treatment in stock or buying a specialist piece of equipment. This can only really be answered on an individual practice basis as it will depend on the type of cases seen as well as the likely ability of clients to want to pay if the treatment/investigation is expensive and the relationship with other local practices in terms of borrowing treatments or using equipment. It is also important to try and understand the value that a particular drug or treatment will have on morbidity and mortality of a particular condition and whether the patient could be referred onwards if necessary so not having calcium available if presented with a seizuring hypocalcaemic patient would be a significant issue in that patient’s care. -

Platelet Transfusion

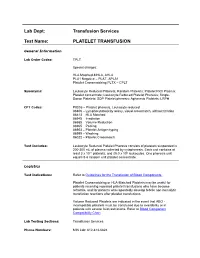

Lab Dept: Transfusion Services Test Name: PLATELET TRANSFUSION General Information Lab Order Codes: TPLT Special charges: HLA Matched-MHLA, AHLA PLA1 Negative – PLAT, APLA1 Platelet Crossmatching PLTX – CPLT Synonyms: Leukocyte Reduced Platelets; Random Platelets; Platelet Rich Plasma; Platelet concentrate; Leukocyte Reduced Platelet Pheresis; Single- Donor Platelets; SDP Platelet pheresis; Apheresis Platelets; LRPH CPT Codes: P9035 – Platelet pheresis, Leukocyte reduced 86806 – Lymphocytotoxicity assay, visual crossmatch, without titration 86813 – HLA Matched 86945 – Irradiation 86985 – Volume Reduction 86965 – Pooling 86903 – Platelet Antigen typing 86999 – Washing 86022 – Platelet Crossmatch Test Includes: Leukocyte Reduced Platelet Pheresis consists of platelets suspended in 200-300 mL of plasma collected by cytapheresis. Each unit contains at least 3 x 1011 platelets, and ≤5.0 x 106 leukocytes. One pheresis unit equals 5-6 random unit platelet concentrate. Logistics Test Indications: Refer to Guidelines for the Transfusion of Blood Components. Platelet Crossmatching or HLA-Matched Platelets may be useful for patients receiving repeated platelet transfusions who have become refractile, and for patients who repeatedly develop febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions after platelet transfusions. Volume Reduced Platelets are indicated in the event that ABO - incompatible platelets must be transfused due to availability or in patients with severe fluid restrictions. Refer to Blood Component Compatibility Chart Lab Testing Sections: Transfusion Services Phone Numbers: MIN Lab: 612-813-6824 STP Lab: 651-220-6558 Test Availability: Daily, 24 hours Turnaround Time: 1 - 2 hours Standard Dose/Volume: <10 kg: 10 – 15 mL/kg up to one unit or 50 mL maximum 10 – 15 kg: 1/3 pheresis unit 15 – 25 kg: 1/2 pheresis unit >25 kg: 1 pheresis unit Rate of Infusion: 10 minutes/unit, <4 hours Administration: Must be administered through a blood component administration filter. -

Blood Banking/Transfusion Medicine Fellowship Program

DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY AND LABORATORY MEDICINE BLOOD BANKING/TRANSFUSION MEDICINE FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM THIS NEW ONE-YEAR ACGME-ACCREDITED FELLOWSHIP IN BLOOD BANKING/TRANSFUSION MEDICINE OFFERS STATE OF THE ART COMPREHENSIVE TRAINING IN BLOOD BANKING, COAGULATION, APHERESIS, AND HEMOTHERAPY AT THE MEMORIAL HERMANN HOSPITAL (MHH)-TEXAS MEDICAL CENTER (TMC) FOR PEDIATRICS AND ADULTS. This clinically-oriented fellowship is ideal for the candidate looking for exceptional experience in hemotherapy decision-making and coagulation consultation. We have a full spectrum of medical and surgical specialties, including a level 1 trauma center, as well as a busy solid organ transplant service (renal, liver, pancreas, cardiac, and lung). Fellows will rotate through: Our unique hemotherapy service: This innovative clinical consultative service for the Heart and Vascular Institute (HVI) allows fellows to serve as interventional blood banking consultants at the bed side as part of a multidisciplinary care team; our patients have complex bleeding and coagulopathy issues. Therapeutic apheresis service: This consultative service provide 24/7 direct patient care covering therapeutic plasmapheresis, red blood cell (RBC) exchanges, photopheresis, plateletpheresis, leukoreduction, therapeutic phlebotomies, and other related procedures on an inpatient and outpatient basis. We performed approximately over 1000 therapeutic plasma exchanges and RBC exchanges every year. Bloodbank: The MHH-TMC reference lab is one of the largest in Southeast Texas. This rotation provides extensive experience in interpreting antibody panel reports, working up transfusion reactions, investigating blood compatibility/incompatibility issues, and monitoring component usage. Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center: This rotation provides donor exposure in one of the largest community blood donation centers in the US as well as cellular therapy and immunohematology training. -

Patient's Guide to Blood Transfusions

Health Information For Patients and the Community A Patient’s Guide to Blood Transfusions Your doctor may order a blood transfusion as part of your therapy. This brochure will focus on frequently asked questions about blood products, transfusions, and the risks and benefits of the blood transfusion. PLEASE NOTE: This information is not intended to replace the medical advice of your doctor or health care provider and is intended for educational purposes only. Individual circumstances will affect your individual risks and benefits. Please discuss any questions or concerns with your doctor. What is a blood transfusion? A blood transfusion is donated blood given to patients with abnormal blood levels. The patient may have abnormal blood levels due to blood loss from trauma or surgery, or as a result of certain medical problems. The transfusion is done with one or more of the following parts of blood: red blood cells, platelets, plasma, or cryoprecipitate. What are the potential benefits of a blood transfusion? If your body does not have enough of one of the components of blood, you may develop serious life-threatening complications. • Red blood cells carry oxygen through your body to your heart and brain. Adequate oxygen is very important to maintain life. • Platelets and cryoprecipitate help to prevent or control bleeding. • Plasma replaces blood volume and also may help to prevent or control bleeding. How safe are blood transfusions? Blood donors are asked many questions about their health, behavior, and travel history in order to ensure that the blood supply is as safe as it can be. Only people who pass the survey are allowed to donate. -

Transfusion Medicine/Blood Banking

Transfusion Medicine/Blood Banking REQUIRED rotation This is a onetime rotation and is not planned by PGY level. Objective: The objective of this rotation is to teach fellows the clinical and laboratory aspects of Transfusion Medicine and Blood Banking as it impacts hematology/oncology. Goals: The goal of this rotation is to teach fellows blood ordering practices, the difference of type and screen and type and cross matches and selection of appropriate products for transfusion. Fellows will also learn to perform, watch type and screen red cell antibodies and will learn the significance of ABO, Rh and other blood group antigen systems briefly so as to understand the significance of red cell antibodies in transfusion practices. Fellows will learn the different types of Blood components, their indications and contraindications and component modification. e.g. Irradiated and washed products, and special product request and transfusions e.g. granulocyte transfusion, CMV negative products etc. Fellows will learn and become proficient in the laboratory aspects of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, coagulopathies and bleeding disorders in relation to massive transfusions and the laboratory aspects and management of platelet refractoriness. Fellows will learn some aspects of coagulation factor replacement for factor deficiencies and inhibitors. Activities: Fellows will rotate in the Blood Bank at UMC and learn to perform, observe and interpret standard blood bank procedures such as ABO Rh typing, Antibody Screen, Antibody Identification and Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT). Fellows will also watch platelet cross matching for platelet refractoriness. Fellows will attend and present a few didactic lectures of about 40 minutes on Blood Bank related topics as they apply to hematology/oncology like blood group antigens, Blood Component therapy, Transfusion reactions, Autoimmune hemolytic anemia, Platelet immunology and HLA as it applies to transfusion medicine. -

Blood Product Modifications: Leukofiltration, Irradiation and Washing

Blood Product Modifications: Leukofiltration, Irradiation and Washing 1. Leukocyte Reduction Definitions and Standards: o Process also known as leukoreduction, or leukofiltration o Applicable AABB Standards, 25th ed. Leukocyte-reduced RBCs At least 85% of original RBCs < 5 x 106 WBCs in 95% of units tested . Leukocyte-reduced Platelet Concentrates: At least 5.5 x 1010 platelets in 75% of units tested < 8.3 x 105 WBCs in 95% of units tested pH≥6.2 in at least 90% of units tested . Leukocyte-reduced Apheresis Platelets: At least 3.0 x 1011 platelets in 90% of units tested < 5.0 x 106 WBCs 95% of units tested pH≥6.2 in at least 90% of units tested Methods o Filter: “Fourth-generation” filters remove 99.99% WBCs o Apheresis methods: most apheresis machines have built-in leukoreduction mechanisms o Less efficient methods of reducing WBC content . Washing, deglycerolizing after thawing a frozen unit, centrifugation . These methods do not meet requirement of < 5.0 x 106 WBCs per unit of RBCs/apheresis platelets. Types of leukofiltration/leukoreduction o “Pre-storage” . Done within 24 hours of collection . May use inline filters at time of collection (apheresis) or post collection o “Pre-transfusion” leukoreduction/bedside leukoreduction . Done prior to transfusion . “Bedside” leukoreduction uses gravity-based filters at time of transfusion. Least desirable given variability in practice and absence of proficiency . Alternatively performed by transfusion service prior to issuing Benefits of leukoreduction o Prevention of alloimmunization to donor HLA antigens . Anti-HLA can mediate graft rejection and immune mediated destruction of platelets o Leukoreduced products are indicated for transplant recipients or patients who are likely platelet transfusion dependent o Prevention of febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions (FNHTR) .