Challenges to Creating and Promoting a Diverse Record: Manuscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manuscripts and University Archives at Florida State University Libraries Robert Rubero, Sandra Varry, Rory Grennan, and Krystal Thomas

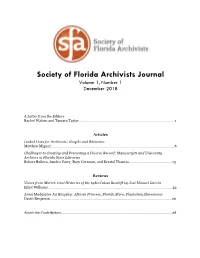

Society of Florida Archivists Journal Volume 1, Number 1 December 2018 A Letter from the Editors Rachel Walton and Tomaro Taylor…….……………………..…………………………………………………………1 Articles Linked Data for Archivists: Graphs and Rhizomes Matthew Miguez……………………………………………………..…………………………………………………………6 Challenges to Creating and Promoting a Diverse Record: Manuscripts and University Archives at Florida State Libraries Robert Rubero, Sandra Varry, Rory Grennan, and Krystal Thomas………………………………………13 Reviews Voices from Mariel: Oral Histories of the 1980 Cuban Boatlift by José Manuel García Elliot Williams…...…………………………………………………………………………………………………………...24 Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley: African Princess, Florida Slave, Plantation Slaveowner David Benjamin.……………………………………………………………………………..………………………………26 About the Contributors…………………………………………………………………….………………………………28 Society of Florida Archivists Journal Vol. 1, No. 1 December 2018 A Letter from the Editors Introducing the Society of Florida Archivists Journal This is the first issue of the Society of Florida Archivists Journal. It may be small, but there is no question, it packs a big punch. As the editors of this journal we can declare honestly and openly that this issue was a long time in the making and that is has only been made possible through the combined efforts of a truly dedicated Editorial Board. We want to recognize this hardworking group of archives professionals for their commitment to the scholarly conversation of our field. They devote themselves to establishing and enacting rigorous peer review criteria and procedures; they engage in many stages of painstaking editorial and formatting work; and they continuously lay the groundwork for a journal that will contribute to our professional practice. A huge and incredibly deserved thank you to Hannah Wiatt Davis, Andrea Malanowski, Jinfang Niu, and Rachel Simmons. -

Cougar History and Awards

Cougar History and Awards 133 2008 COUGAR FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE honors FRANK BUTLER AWARD WINNERS LAURIE NIEMI AWARD WINNERS Awarded annually to a senior member of the Cougar football team who Awarded to the senior who best shows the courage, spirit, and attitude of exemplifies the Cougar spirit that Spokane booster Frank Butler was former Cougar assistant coach Laurie Niemi. famous for. 1968 Steve Bartelle 1971 Chuck Hawthorne 1969 No Winner 1972 Steve Hamilton 1970 Terry Durst 1973 Tom Poe 1971 Brian Lange 1974 Gary Larsen 1972 Mike Johnson 1975 Vern Chamberlain 1973 Craig Craighead 1976 Tim Ochs 1974 Steve Ostermann 1977 Dan Doornink 1975 Carl Barschig 1978 Jack Thompson 1976 Jon DesPois 1979 Bevan Maxey 1977 Don Hover 1979 Bob Gregor 1978 Mark Chandless 1980 Samoa Samoa 1979 Tali Ena 1981 Jeff Keller 1980 Jim Whatley 1982 Gary Patrick 1981 Ken Collins 1983 Sonny Elkinton 1982 Ken Emmil 1984 Dan Lynch 1983 Pat Lynch 1985 Curt Ladines 1984 Brent White 1986 Rick Chase Jamie White 1987 Chris Hiller 1985 Mike Dreyer 1988 Artie Holmes 1986 Ron Collins 1989 Mark Ledbetter 1987 Brian Forde 1990 Dan Webber James Hasty 1991 Jay Reyna 1988 Ivan Cook 1992 C. J. Davis 1989 Paul Wulff Robbie Tobeck 1990 Chris Moton 1993 Josh Dunning 1991 Lee Tilleman 1994 Payam Saadat 1992 Lewis Bush 1995 Eric Moore 1993 Mike Pattinson 1996 David Knuff 1994 Ron Childs 1997 Dorian Boose 1995 Greg Burns 1998 Rob Rainville 1996 James Darling 1999 Steve Gleason 1997 Leon Bender 2000 Adam Hawkins 1998 Dee Moronkola 2007 Niemi Award winner 2001 Jeremy Thielbahr 1999 Steve Gleason Chris Baltzer 2002 Collin Henderson 2007 Butler Award winner 2000 Austin Matson 2003 Jason David Michael Bumpus 2001 Dave Minnich 2004 Jeremy Bohannon 2002 Mawuli Davis 2005 Troy Bienemann 2005 Marty Martin 2003 Jeremey Williams 2006 Scott Davis 2006 Mkristo Bruce 2004 Hamza Abdullah 2007 Chris Baltzer 2007 Michael Bumpus J. -

The Florida Bar Celebrates 70 Years

SPRING / SUMMER 2020 A Publication of THE FLORIDA SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE FLORIDA BAR CELEBRATES 70 YEARS 70 YEARS OF THE FLORIDA THE FLORIDA CUBAN-AMERICAN THE FLORIDA BAR BAR COMPLEX BAR EXAM LAWYERS PROGRAM PAGE 8 PAGE 12 PAGE 15 PAGE 19 Contents 4 19 FLORIDA President’s LEGAL HISTORY Column The Florida Jonathan F. Claussen Bar’s Cuban- American Lawyers 6 Program Chief Raul Alvarez Justice’s Message C.J. Charles Canady 23 FLORIDA LEGAL HISTORY 8 History of FLORIDA the FBBE LEGAL HISTORY Dr. Steven Maxwell 70 Years of The Florida Bar 28 Catherine Awasthi FLORIDA SUPREME COURT NEWS Court Hosts 12 Online Oral FLORIDA Arguments LEGAL HISTORY During The Florida Pandemic Bar Complex Kimberly Kanoff Berman Ali Bowlby 30 15 HISTORICAL FLORIDA SOCIETY EVENTS LEGAL HISTORY A Supreme The Florida Evening 2020 Bar Exam Mark A. Miller Sara Shapiro 33 16 CURRENT EVENTS LEGAL HISTORY Court Hosts The 100th FSU Law Anniversary th Moot Court of the 19 FSU Law Students Amendment Amani Kmeid 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW SPRING / SUMMER 2020 EDITOR’S MESSAGE irst and foremost, I hope Florida Supreme Court this finds you and your Historical Society Ffamily safe and well. Since the last issue, the country has SPRING / SUMMER 2020 experienced a historical pandemic that uprooted our daily lives. While EDITOR this issue focuses on celebrating 70 Melanie Kalmanson, Esq. years of The Florida Bar, it is not meant to ignore the challenges and EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE resilience Florida, and especially Edward Guedes, Esq. its legal community, has shown in Dr. Steven Maxwell weathering COVID-19. -

Storical Uarterly

The storical uarterly J ANUARY 1966 Published by THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF FLORIDA, 1856 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, successor, 1902 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, incorporated, 1905 by GEORGE R. FAIRBANKS, FRANCIS P. FLEMING, GEORGE W. WILSON, CHARLES M. COOPER, JAMES P. TALIAFERRO, V. W. SHIELDS, WILLIAM A. BLOUNT, GEORGE P. RANEY. O FFICERS JAMES R. KNOTT, president WILLIAM M. GOZA, 1st vice president REMBERT W. PATRICK, 2nd vice president LUCIUS S. RUDER, honorary vice president MRS. RALPH DAVIS, recording secretary MARGARET CHAPMAN, executive secretary D IRECTORS CHARLES O. ANDREWS JAY I. KISLAK JAMES C. CRAIG FRANK J. LAUMER ALLEN C. CROWLEY WILLIAM W. ROGERS HERBERT J. DOHERTY, JR. MARY TURNER RULE DAVID FORSHAY MORRIS WHITE WALTER P. FULLER LEONARD A. USINA JOHN E. JOHNS FRANK B. SESSA, ex-officio SAMUEL PROCTOR, ex-officio (and the officers) (All correspondence relating to Society business, memberships, and Quarterly subscriptions should be addressed to Miss Margaret Chapman, University of South Florida Library, Tampa, Florida 33620. Articles for publication, books for review, and editorial correspondence should be ad- dressed to the Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida.) . To explore the field of Florida history, to seek and gather up the ancient chronicles in which its annals are contained, to retain the legendary lore which may yet throw light upon the past, to trace its monuments and remains to elucidate what has been written to disprove the false and support the true, to do justice to the men who have figured in the olden time, to keep and preserve all that is known in trust for those who are to come after us, to increase and extend the knowledge of our history, and to teach our children that first essential knowledge, the history of our State, are objects well worthy of our best efforts. -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

THE SMOKEY HOLLOW COMMUNITY HALS FL-9 Informal boundaries by street name: North to South: E. Jefferson HALS FL-9 Street to E. Van Buren Street. West to East: S. Gadsden Street to Marvin Street. Tallahassee Leon County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY SMOKEY HOLLOW (Smoky Hollow) Location: Site of displaced Smokey Hollow community, Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida Informal boundaries by street name: North to South: E. Jefferson Street to E. Van Buren Street. West to East: S. Gadsden Street to Marvin Street. Latitude 30.434478° and Longitude ‐84.277108° (The Tallahassee Meridian survey monument) Present Owner: City of Tallahassee and state of Florida Present Occupant: Non‐residential Present Use: City of Tallahassee public space, state of Florida offices Significance: The story of Smokey Hollow forces us to rethink historical narratives of government’s exercise of eminent domain in the mid‐twentieth century on established African American neighborhoods. Throughout the nation, government intervention displaced vibrant communities of working class people, immigrants, and minorities. While the specific contours of that story in Tallahassee were unique, the outcome was not. Through the power of eminent domain, the state of Florida eliminated most of the housing and business structures that had existed in Smokey Hollow since the turn of the twentieth century. Yet, that dissolution did not eradicate the community’s sense of itself. This is the story of the development of this African American community, its dissolution, and its persistence in memory after dislocation. -

Report R.Esumes

REPORT R.ESUMES ED 013 381 24 AA 000 236 INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCHAND THE ACADEMIC PROGRAM.NEW DIMENSIONS IN HIGHER EDUCATION,NUMBER 20. BY- BOYER, ERNESTL. DUKE UNIV., DURHAM, N.C. REPORT NUMBER BR -6- 1722-20 PUB DATE APR 67 CONTRACT OEC--2-.6--061722-.1742 EDRS PRICE. MF -$0.50 HC-.43.04 76P. DESCRIPTORS-. *INSTITUTIONS,*RESEARCH, *CLEGE PROGRAMS, PROFESSORS, CHANGE AGENTS,HIGHER EDUCATION, ':EDUCATIONAL CHANGE, *ACADEMIC EDUCATION,LITERATURE REVIEWS, A SEARCH OF THE LITERATUREON INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCHWAS MADE TO FIND AN ANSWERTO ONE QUESTIN-.--10 WHATEXTENT HAS INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH ACTUALLYHELPED IMPROVE COLLEGIATE LIFE GENERALLY AND THEACADEMIC PROGRAM IN PARTICULAR.FROM THE SEARCH; THE AUTHORDRAWS THE CONCLUSION THAT THERECENT FLURRY OF RESEARCH ACTIVITYHAS NOT BEEN ACCOMPANIED BYA LARGE AMOUNT Cf EFFECT. LITTLEDIRECT EVIDENCE ABOUT THE IMPACT OF INSTITUTIONALRESEARCH WAS FOUND. JUDGEMENTCf THE EFFECTS CF THIS RESEARCHWAS MADE FROM INDIRECT EVIDENCEAND FROM THE CFININS CF INFORMEDOBSERVERS. THE REPORT EXAMINES THOSE ASPECTS Cf HIGHEREDUCATION THAT HAVE CHANGED,THOSE THAT HAVE REMAINED RELATIVELYSTABLE, AND THE DEGREE TO WHICH INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH MAYOR MAY NOT HAVE BEEN ASIGNIFICANT FORCE. REPRESENTATIVESTUDIES ARE CITED, AND THE FINAL SECTION DISCUSSES WAYS IN WHICHINSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH MIGHT INCREASE ITS IMPACT IN THEFUTURE. THE AUTHCiR CONCLUDESTHAT (1) IN PART, THE FAILUREOF INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCHTO AFFECT ACADEMIC AFFAIRS DIRECTLY ANDSUBSTANTIALLY CAN BE ATTRIBUTED TO INTERNAL SHORTCOMINGSCf THE PROFESSION THATRELATE TO STRUCTURE, FUNCTION, THEORY,AND STYLE OF COMMUNICATION,AND (2) THE FUTURE EFFECTS CFACADEMIC RESEARCH WILL HINGEON THE WILLINGNESS OF EDUCATORS TO VIEWCHANGE AS AN ALLY RATHER THAN AS AN IMPEDIMENT. (AL) ri Pit CC) re\ 1141 1117BENW in Higher Education Ui Number 20 INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH AND THE ACADEMIC PROGRAM April, 1967 The literature research review reported in this manuscript was made possible by Contract Number OEC 2-6-061722-1742 between Duke University, Durham, North Carolina and the United States Office of Education.