Of Beach Balls, the San Andreas and Cascadia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's Shaking

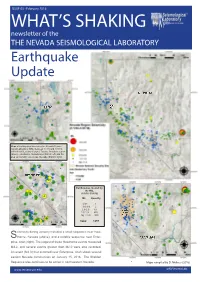

ISSUE 03 - February 2016 WHAT’S SHAKING newsletter of the THE NEVADA SEISMOLOGICAL LABORATORY Earthquake Update NEVADA Carson RENO City Maps of earthquakes located by the Nevada Seismo- logical Laboratory (NSL) between 1/1/16 and 1/31/16, within the NSL network (right). Truckee Meadows region (above), Hawthorne, Nevada area (bottom left) and the area surrounding Las Vegas, Nevada (bottom right). HAWTHORNE Earthquakes located by the NSL (1/1/16-1/31/16) ML Quantity 4.0+ 1 3.0-3.9 2 2.0-2.9 67 Nevada 1.0-1.9 478 National ML < 1.0 809 Security Site Total 1357 eismicity during January included a small sequence near Haw- Sthorne, Nevada (above), and a notable sequence near Enter- LAS VEGAS prise, Utah (right). The largest of these Hawthorne events measured M3.2, and several events greater than M2.0 were also recorded. An event (M4.3) that occurred near Enterprise, Utah shook several eastern Nevada communities on January 15, 2016. The Sheldon Sequence also continues to be active in northwestern Nevada. Maps compiled by D. Molisee (2016) www.graphicdiffer.comwww.seismo.unr.edu @NVSeismoLab1 DEVELOPMENTS NSL Graduate Students Leverage Funding from the National Science Foundation unding for Steve Angster and will focus on the Agai-Pai, Indian FIan Pierce has come from Head, Gumdrop, Benton Springs, a National Science Foundation and Petrified fault systems, while grant (Steve Wesnousky, lead PI) Ian will study the Tahoe, Carson, focused on the deformation pat- Antelope Valley, Smith Valley, Ma- tern and kinematics of the Walker son Valley, and Walker Lake fault Lane. -

This Report Is Preliminary and Has Not Bee Reviewed for Conformity with US

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Northeast-trending subcrustal fault transects western Washington by Kenneth F. Fox, Jr.* Open-File Report 83-398 This report is preliminary and has not bee reviewed for conformity with U.S Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. *U.S. Geological Survey 3^5 Middlefield Road Menlo Park, California 9^025 Page Table of Contents Tectonic setting......................................................... 1 Seisraicity............................................................... 4 Discussion............................................................... 4 References cited......................................................... 6 Figures Figure 1. Magnetic anomalies in the northeastern Pacific................ 8 Figure 2. Bathymetry at intersection of Columbia lineament and Blanco fracture zone................................................. 9 Figure 3. Plane vector representation of movement of Gorda plate........ 10 Figure 4. Reconstruction of Pacific-Juan de Fuca plate geometry 2 m.y. before present................................................ 11 Figure 5. Epicenters of historical earthquakes with intensity greater than V........................................................ 12 TECTONIC SETTING The north-trending magnetic anomalies of the Juan de Fuca plate are off set along two conspicuous northeast-trending lineaments (fig. 1), named the Columbia offset and the Destruction offset by Carlson (1981). The northeast ward projections of these lineaments intersect the continental area of western Washington, hence are of potential significance to the tectonics of the Pacific Northwest region. Pavoni (1966) suggested that these lineaments were left-lateral faults, and that the Columbia, 280 km in length, had 52 km of offset, and the Destruction, with a length of 370 km, had 75 km of offset. Based on Vine's (1968) correlation of the magnetic anomalies mapped in this area by Raff and Mason (1961), with the magnetic reversal time scale, Silver (1971b, p. -

Geologic History of Siletzia, a Large Igneous Province in the Oregon And

Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Wells, R., Bukry, D., Friedman, R., Pyle, D., Duncan, R., Haeussler, P., & Wooden, J. (2014). Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot. Geosphere, 10 (4), 692-719. doi:10.1130/GES01018.1 10.1130/GES01018.1 Geological Society of America Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Downloaded from geosphere.gsapubs.org on September 10, 2014 Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Ray Wells1, David Bukry1, Richard Friedman2, Doug Pyle3, Robert Duncan4, Peter Haeussler5, and Joe Wooden6 1U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, Menlo Park, California 94025-3561, USA 2Pacifi c Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research, Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, 6339 Stores Road, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada 3Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1680 East West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA 4College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, 104 CEOAS Administration Building, Corvallis, Oregon 97331-5503, USA 5U.S. Geological Survey, 4210 University Drive, Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4626, USA 6School of Earth Sciences, Stanford University, 397 Panama Mall Mitchell Building 101, Stanford, California 94305-2210, USA ABSTRACT frames, the Yellowstone hotspot (YHS) is on southern Vancouver Island (Canada) to Rose- or near an inferred northeast-striking Kula- burg, Oregon (Fig. -

On the Dynamics of the Juan De Fuca Plate

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 189 (2001) 115^131 www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl On the dynamics of the Juan de Fuca plate Rob Govers *, Paul Th. Meijer Faculty of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, P.O. Box 80.021, 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands Received 11 October 2000; received in revised form 17 April 2001; accepted 27 April 2001 Abstract The Juan de Fuca plate is currently fragmenting along the Nootka fault zone in the north, while the Gorda region in the south shows no evidence of fragmentation. This difference is surprising, as both the northern and southern regions are young relative to the central Juan de Fuca plate. We develop stress models for the Juan de Fuca plate to understand this pattern of breakup. Another objective of our study follows from our hypothesis that small plates are partially driven by larger neighbor plates. The transform push force has been proposed to be such a dynamic interaction between the small Juan de Fuca plate and the Pacific plate. We aim to establish the relative importance of transform push for Juan de Fuca dynamics. Balancing torques from plate tectonic forces like slab pull, ridge push and various resistive forces, we first derive two groups of force models: models which require transform push across the Mendocino Transform fault and models which do not. Intraplate stress orientations computed on the basis of the force models are all close to identical. Orientations of predicted stresses are in agreement with observations. Stress magnitudes are sensitive to the force model we use, but as we have no stress magnitude observations we have no means of discriminating between force models. -

Cascadia Low Frequency Earthquakes at the Base of an Overpressured Subduction Shear Zone ✉ Andrew J

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17609-3 OPEN Cascadia low frequency earthquakes at the base of an overpressured subduction shear zone ✉ Andrew J. Calvert 1 , Michael G. Bostock 2, Geneviève Savard 3 & Martyn J. Unsworth4 In subduction zones, landward dipping regions of low shear wave velocity and elevated Poisson’s ratio, which can extend to at least 120 km depth, are interpreted to be all or part of the subducting igneous oceanic crust. This crust is considered to be overpressured, because fl 1234567890():,; uids within it are trapped beneath an impermeable seal along the overlying inter-plate boundary. Here we show that during slow slip on the plate boundary beneath southern Vancouver Island, low frequency earthquakes occur immediately below both the landward dipping region of high Poisson’s ratio and a 6–10 km thick shear zone revealed by seismic reflections. The plate boundary here either corresponds to the low frequency earthquakes or to the anomalous elastic properties in the lower 3–5 km of the shear zone immediately above them. This zone of high Poisson’s ratio, which approximately coincides with an electrically conductive layer, can be explained by slab-derived fluids trapped at near-lithostatic pore pressures. 1 Department of Earth Sciences, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada. 2 Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, 2207 Main Mall, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada. 3 Department of Geosciences, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4, Canada. 4 Department of Physics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2E9, Canada. -

Deep-Water Turbidites As Holocene Earthquake Proxies: the Cascadia Subduction Zone and Northern San Andreas Fault Systems

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Faculty Publications 10-1-2003 Deep-water turbidites as Holocene earthquake proxies: the Cascadia subduction zone and Northern San Andreas Fault systems Chris Goldfinger Oregon State University C. Hans Nelson Universidad de Granada Joel E. Johnson University of New Hampshire, Durham, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Goldfinger, C. Nelson, C.H., and Johnson, J.E., 2003, Deep-Water Turbidites as Holocene Earthquake Proxies: The Cascadia Subduction Zone and Northern San Andreas Fault Systems. Annals of Geophysics, 46(5), 1169-1194. http://dx.doi.org/10.4401%2Fag-3452 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANNALS OF GEOPHYSICS, VOL. 46, N. 5, October 2003 Deep-water turbidites as Holocene earthquake proxies: the Cascadia subduction zone and Northern San Andreas Fault systems Chris Goldfinger (1),C. Hans Nelson (2) (*), Joel E. Johnson (1)and the Shipboard Scientific Party (1) College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, U.S.A. (2) Department of Oceanography, Texas A & M University, College Station, Texas, U.S.A. Abstract New stratigraphic evidence from the Cascadia margin demonstrates that 13 earthquakes ruptured the margin from Vancouver Island to at least the California border following the catastrophic eruption of Mount Mazama. These 13 events have occurred with an average repeat time of ¾ 600 years since the first post-Mazama event ¾ 7500 years ago. -

New Stratigraphic Evidence from the Cascadia Margin Demonstrates That

Agency: U. S. Geological Survey Award Number: 03HQGR0059 Project Title: Holocene Seismicity of the Northern San Andreas Fault Based on Precise Dating of the Turbidite Event Record. Collaborative Research with Oregon State University and Granada University. End Date: 12/31/2003 Final Technical Report Keywords: Paleoseismology Recurrence interval Rupture characteristics Age Dating Principle Investigators: Chris Goldfinger College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331; email: [email protected] C. Hans Nelson Now at Instituto Andaluz de Ciencias de la Tierra, CSIC, Universidad de Granada, Campus de Fuente Nueva s/n ,Granada,18071 Graduate Student: Joel E. Johnson College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331; email: [email protected] Northern San Andreas Seismotectonic Setting The San Andreas Fault is probably the best-known transform system in the world. Extending along the west cost of North America, from the Salton Sea to Cape Mendocino, it is the largest component of a complex and wide plate boundary that extends eastward to encompass numerous other strike-slip fault strands and interactions with the Basin and Range extensional province. The Mendocino Triple junction lies at the termination of the northern San Andreas, and has migrated northward since about 25-28 Ma. As the triple junction moves, the former subduction forearc transitions to right lateral transform motion. West of the Sierra Nevada block, three main fault systems accommodate ~75% of the Pacific-North America plate motion, distributed over a 100 km wide zone (Argus and Gordon, 1991). The remainder is carried by the Eastern California Shear Zone (Argus and Gordon, 1991; Sauber, 1994). -

Internal Deformation of the Southern Gorda Plate: Fragmentation of a Weak Plate Near the Mendocino Triple Junction

Internal deformation of the southern Gorda plate: Fragmentation of a weak plate near the Mendocino triple junction Sean P.S. Gulick* Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania 18015, Anne S. Meltzer USA Timothy J. Henstock* Department of Geology and Geophysics, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, USA Alan Levander ABSTRACT Gorda plate that may serve as the northern North-south compression across the Gorda-Paci®c plate boundary caused by the north- limit of in¯uence of the triple junction on the ward-migrating Mendocino triple junction appears to reactivate Gorda plate normal Juan de Fuca±Gorda plate system. Near the faults, originally formed at the spreading ridge, as left-lateral strike-slip faults. Both seis- triple junction, the plate shows evidence of mically imaged faults and magnetic anomalies fan eastward from ;N208E near the Gorda fragmenting (Fig. 1B). ridge to ;N758E near the triple junction. Near the triple junction, the Gorda plate is faulted pervasively and appears to be extending east-southeast as it subducts beneath GORDA PLATE DEFORMATION North America. Continuation of northeast-southwest±oriented deformation in the southern Oceanic crust imaged on seismic lines Gorda plate beneath the continental margin contrasts with the northwest-southeast±trend- MTJ-3, MTJ-5, and MTJ-6 is rough and per- ing structures in the overlying accretionary prism, suggesting partial Gorda±North Amer- vasively faulted (Fig. 3). The crust appears in ican plate decoupling. Southeast of the triple junction, a slabless window is generated by places to be broken into crustal blocks bound- removal of the subducting Gorda plate. -

Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquake Scenario

CCaassccaaddiiaa SSuubbdduuccttiioonn ZZoonnee EEaarrtthhqquuaakkeess:: AA MMaaggnniittuuddee 99..00 EEaarrtthhqquuaakkee SScceennaarriioo Update, 2013 Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup Also available as Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Information Circular 116, Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Open-File Report 0-13-22, and British Columbia Geological Survey Information Circular 2013-3 Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup (CREW) CREW is a non-profit coalition of business people, emergency managers, scientists, engineers, civic leaders, and government officials who are working together to reduce the effects of earthquakes in the Pacific Northwest. Executive Board President: John Schelling, Washington Emergency Management Division Vice President: Michael Kubler, Emergency Management, Providence Health & Services, Portland, OR Past President: Cale Ash, Degenkolb Engineers Secretary: Teron Moore, Emergency Management, British Columbia Treasurer: Timothy Walsh, State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Executive Director: Heidi Kandathil Board of Directors Steven Bibby, Security and Emergency Services, BC Housing Josh Bruce, Oregon Partnership for Disaster Resilience Kathryn Forge, Public Safety Canada Jere High, Oregon State Public Health Division Andre LeDuc, University of Oregon Charlie Macaulay, Global Risk Consultants Ines Pearce, Pearce Global Partners Althea Rizzo, Oregon Emergency Management Bill Steele, University of Washington, Pacific Northwest Seismic Network Yumei Wang, Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Supporting members Tamra Biasco, FEMA, Region X Craig Weaver, U.S. Geological Survey Joan Gomberg, U.S. Geological Survey Nate Wood, U.S. Geological Survey Acknowledgments CREW would like to thank Tamra Biasco and Joan Gomberg for overseeing the development of this updated edition of Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquakes: A Magnitude 9.0 Earthquake Scenario. We would also like to thank everyone who shared information and materials or contributed their time and expertise to this project. -

The Gorda Deformation Zone

The Gorda Deformation Zone Miles Bodmer University of Oregon Goals • Better understand deformation of the Gorda Plate • Look at deformation at a range of depths (crust – lithosphere - asthenosphere) • Highlight some of my research What Makes The Gorda Interesting? • The Gorda is the oceanic plate outboard of southern Cascadia subduction zone • Southern Cascadia is where large megathrust earthquakes are thought to nucleate • 1/3 of the plate configuration that makes up the Mendocino triple junction • Seismically active Modified from Byrnes et al. (2017) Tectonic History • ~10 Ma Pacific plate motion changes • Ridges begin to reorganize • ~5 Ma the Blanco transform develops • ~4 MA Explorer plate breaks off • The Mendocino transform and Gorda ridge fail to reorient Atwater and Stock, 1998 Magnetic Anomalies • Clear bending of anomalies in Gorda • Juan de Fuca shows signs of reorganization • Formation of new segments • Ridge rotation • Pacific side near Gorda does not show similar signs of reorganization • Variable spreading rates Wilson (2002) Gorda Is Stagnating • Gorda motion becomes increasingly independent in the last 3 Ma • At 0.5 Ma the Pacific controls Gorda motion Riddihough (1984) Seismicity Throughout The Plate 1964 – 1980 Star: M 5.7 (Jay Patton http://earthjay.com/) Wilson (1989) Historic seismicity (USGS www.earthquake.usgs.gov) Large Events In The Plate Correlate With Bathymetry Chaytor (http://activetectonics.coas.oregonstate.edu/gorda.htm) Deformation Accommodated By Left-lateral Faults • Bathymetry clearly shows ridges associated with faulting • Ridges appear smoothly deformed, kinked, or undeformed depending on the region • Moment tensors show dominantly left-lateral strike-slip motion with some normal faulting • Faults show clear regions of deformation Chaytor et al. -

Preliminary Estimates of Future Earthquake Losses

Earthquake damage in Oregon: Preliminary estimates of future earthquake losses Cascadia Subduction lone earthquake model: Least dangerous areas are yellow, most dangerous are darkest red. 500 year recurrence interval model (including many earth quakes): Least dangerous areas are yellow, most dangerous are darkest red. - l Special Paper 29 by Yumei Wang and J. L. Clark Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries 1999 Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Special Papers, JSSN 0278-3703 PUblished in conformance with ORS 516.030 This report is a summay of a more complete description of a Deportment of Geology and Minerallndus1ries study. Open-File Report 0-98-3, which contains details about vaious types of acceleration and ground motion and is targeted to scientific and engineering users. as well as emergency planners. For copies of these publications or other information about Oregon's geology and natural resources. contact: Nature of the Northwest Information Center 800 NE Oegon Street #5 Portland. Oegon 972':!2. (503) 872-275) http:/ /www.naturenw.org SPECIAL PAPER 29 EARTHQUAKE DAMAGE IN OREGON: Preliminary estimates of future earthquake losses by Yumei Wang and J.L Clark Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries 1999 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Donald A. Hull. State Geologist Table of Contents Executive summary ................... ... ......................................................... ............... ............ ......... 1 Introduction ................. .. ....... -

Quaternary Rupture of a Crustal Fault Beneath Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

Quaternary Rupture of a Crustal Fault beneath Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Kristin D. Morell, School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia V8P 5C2, Canada, kmorell@ uvic.ca; Christine Regalla, Department of Earth and Environment, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA; Lucinda J. Leonard, School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia V8P 5C2, Canada; Colin Amos, Geology Department, Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington 98225-9080, USA; and Vic Levson, School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia V8P 5C2, Canada ABSTRACT detectable by seismic or geodetic monitor- US$10 billion in damage (Quigley et The seismic potential of crustal faults ing (e.g., Mosher et al., 2000; Balfour et al., al., 2012). within the forearc of the northern Cascadia 2011). This point was exemplified by the In the forearc of the Cascadia subduc- 2010 M 7.1 Darfield, New Zealand tion zone (Fig. 1), where strain accrues due subduction zone in British Columbia has W remained elusive, despite the recognition (Christchurch), earthquake and aftershocks to the combined effects of northeast- of recent seismic activity on nearby fault that ruptured the previously unidentified directed subduction and the northward systems within the Juan de Fuca Strait. In Greendale fault (Gledhill et al., 2011). This migration of the Oregon forearc block this paper, we present the first evidence for crustal fault showed little seismic activity (McCaffrey et al., 2013), microseismicity earthquake surface ruptures along the prior to 2010, but nonetheless produced a data are sparse and do not clearly elucidate Leech River fault, a prominent crustal fault 30-km-long surface rupture, caused more planar crustal faults (Cassidy et al., 2000; near Victoria, British Columbia.