The Wildland/Urban Interface Fire Problem in the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Budget Fiscal Year 2012-2013

CELEBRATING 125 YEARS OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST RODEO ANNUAL BUDGET FISCAL YEAR 2012-2013 City of Prescott, Arizona Annual Budget for fiscal year July 1, 2012 – June 30, 2013 City Council Marlin Kuykendall, Mayor Charlie Arnold Steve Blair Alan Carlow Chris Kuknyo Jim Lamerson Len Scamardo Administrative Staff Craig McConnell City Manager Mark Woodfill Finance Director Jodi Fisher Budget Manager WHAT’S INSIDE PREFACE ENTERPRISE FUNDS Budget Process Overview ............................... 1 Water ..........................................................191 Budget Calendar ............................................. 3 Wastewater ..................................................212 Solid Waste/Transfer Station .......................228 INTRODUCTION Airport ..........................................................235 Golf Course ..................................................240 Organizational Values ..................................... 4 Parking Garage ............................................247 Organizational Chart and City Officials ........... 5 Award for Distinguished Budget Presentation10 INTERNAL SERVICE FUNDS POLICIES AND OBJECTIVES General Self-Insurance ................................249 Fleet Maintenance .......................................252 Budget Policy ................................................ 11 Engineering ..................................................256 Debt Policy .................................................... 15 Facilities Maintenance .................................261 Investment Policy -

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Operations and Data Analysis Prescott, Arizona August 2014

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Operations and Data Analysis Prescott, Arizona August 2014 Submitted by and reply to: ICMA Center for Public Safety Management International City/County Management Association 777 North Capitol Street NE, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20002 [email protected] 202-962-3607 Copyright © 2014 Fire and EMS Operations and Data Analysis: Prescott, AZ page 1 General Information About ICMA The International City/County Management Association (ICMA) is a 100-year-old nonprofit professional association of local government administrators and managers, with approximately 9,000 members located in 28 countries. Since its inception in 1914, ICMA has been dedicated to assisting local governments in providing services to their citizens in an efficient and effective manner. Our work spans all of the activities of local government: parks, libraries, recreation, public works, economic development, code enforcement, brownfields, public safety, and a host of other critical areas. ICMA advances the knowledge of local government best practices across a wide range of platforms, including publications, research, training, and technical assistance. Our work includes both domestic and international activities in partnership with local, state, and federal governments, as well as private foundations. For example, we are involved in a major library research project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and are providing community policing training in El Salvador, Mexico, and Panama with funding from the United States Agency for International Development. We have personnel in Afghanistan helping to build wastewater treatment plants and have teams working with the United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) in Central America on conducting assessments and developing training programs for disaster preparedness. -

Final Photos, Videos of Granite Mountain Hotshots Come to Light

Final photos, videos of Granite Mountain Hotshots come to light... http://dcourier.com/main.asp?SectionID=1&ArticleID=123720 Home | Classifieds | Place an Ad | Public Notices | Subscriber Services | 928 Media Lab | Real Estate Search | Galleries | Obits | TV Listings | Contact Us Find It Blogs Features Milestones Submit Extras Other Publications Circulars Today's Ads home : latest news Share December 11, 2015 Advanced Search Like Share 30 Tweet +1 Recommend this on Google 9/28/2013 10:00:00 AM Final photos, videos of Granite Mountain Hotshots come to light Joanna Dodder Nellans The Daily Courier Christopher MacKenzie left an unexpected gift when he perished alongside 18 of his fellow Granite Click for weather forecast Mountain Hotshots June 30 in the Yarnell Hill wildfire. When his father Mike received Chris' charred belongings from the medical examiner's office, one item appeared untouched by fire: a small Canon PowerShot digital camera. Even the cloth cover was Granite Mountain Hotshot Robert Caldwell stands with a torch after lighting a unscathed. backfire on the Yarnell Hill Fire at 10:45 a.m. on June 30, 2013. Photo recovered from the personal camera of Granite Mountain Hotshot Christopher MacKenzie following the horrific Yarnell Hill Fire that killed 19 of the Granite "My stepdaughter pulled the card Mountain Hotshots on June 30, 2013. out and stuck it in the computer and said, 'Hey, check this out,'" Mike related. He came over and saw photos of the Granite Mountain Hotshots working the Doce wildfire near Prescott June 18-22, as well as the West Spruce wildfire near Prescott on June 28. -

Media Kit Vs1 DRAFT

Jan Brewer Arizona State Forestry Division Governor Office of the State Forester 1110 W. Washington St., Suite 100 Scott Hunt Phoenix, AZ 85007 State Forester (602) 771-1400 For Immediate Release Contact: Carrie Dennett, PIO Sept. 28, 2013 (602) 399-3078 State Forester Releases Yarnell Hill Accident Investigation Report PHOENIX, Ariz. – The Arizona State Forester today released the Yarnell Hill Fire Serious Accident Investigation Report, which analyzes the circumstances leading to the June 30 entrapment and deaths of 19 firefighters of the Granite Mountain Interagency Hotshot Crew. The report and accompanying documents are available at https://sites.google.com/site/yarnellreport/. The State of Arizona convened an accident investigation team July 3 to review the conditions and events leading to the tragedy. The investigation team visited the site of the accident, reviewed audio and video files, interviewed individuals associated with the incident, reviewed fire weather and behavior data, and examined available records and physical evidence. The resulting report contains the most complete information available about the accident. “Our mission was to find out what happened and to discern the facts surrounding this tragedy to the best of our ability,” said Jim Karels, investigation team lead and the State Forester for the Florida Forest Service. “We also hope this report facilitates learning within the wildland fire community in order to reduce the likelihood of repeating actions that contributed to the loss of life.” The 116-page report includes a fact-based narrative of the incident and offers the investigation team’s analysis, conclusions and recommendations. It also includes a discussion section that is meant to facilitate understanding and learning by exploring various perspectives and issues that arose during the investigation. -

SPOKANE COUNTY FIELD OPERATIONS GUIDE and SPOKANE COUNTY FIRE RESOURCE PLAN

SPOKANE COUNTY FIELD OPERATIONS GUIDE and SPOKANE COUNTY FIRE RESOURCE PLAN Inland Empire Fire Chief’s Association Inland Northwest Law Enforcement Leadership Group ICS FOG PREFACE This Field Operations Guide (FOG) was created to assist emergency response agencies of Spokane County and the greater Inland Empire in the art of incident management. It is intended to serve these agencies by promoting a common all-risk Incident Command System (ICS). This document provides an incident management framework to meet an agency’s routine ICS needs as well as expanding to meet the demands of large-scale complex events, which by their nature, demand safe, effective incident management and multi-agency coordination. The Inland Empire Fire Chief’s Association and the Inland Northwest Law Enforcement Leadership Group encourages agencies to utilize this guide as a baseline for managing incident operations recognizing it may need to be supported by additional agency specific policies and guidelines. The Spokane County ICS Field Operations Guide is compatible with and used in conjunction with the Spokane Area Fire Resource Plan, the Washington Fire Mobilization Plan and the Northwest Regional Law Enforcement Mobilization Plan to order and coordinate the use of incident resources. This document should be seen as a “work in progress” and as such will demand periodic review by the Inland Empire Fire Chief’s Association and the Inland Northwest Law Enforcement Leadership Group. Adopted: Inland Empire Fire Chief’s Association Inland Northwest Law Enforcement Leadership Group PREFACE i June 2006 ICS FOG THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK PREFACE ii June 2006 ICS FOG TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Common Responsibilities ............................................................................ -

City of Prescott, Arizona Annual Budget Fiscal Year 2018 July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018

Annual Budget Fiscal Year 2018 City of Prescott, Arizona Annual Budget Fiscal Year 2018 July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018 City Council Harry Oberg, Mayor Billie Orr Greg Lazzell Jean Wilcox Jim Lamerson Steve Sischka Steve Blair Administrative Staff Michael Lamar City Manager Mark Woodfill Finance Director Lars Johnson Budget Manager Table of Contents Budget Award ........................................................................................................................................ 1 City Manager's Budget Message ......................................................................................................... 2 City Leadership and Community Overview ........................................................................................ 4 Mayor and City Council ...................................................................................................................... 5 Community Profile ............................................................................................................................ 12 City of Prescott Demographics ......................................................................................................... 16 Organizational Structure, Goals, and Policies ................................................................................. 20 Organizational Values ...................................................................................................................... 21 City Organizational Chart ................................................................................................................ -

The 2013 Granite Mountain Hotshots (LLC) Team to Our Knees

Summer 2013 ▲ Vol. 3 Issue 2 ▲ Produced and distributed quarterly by the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center I bet you remember exactly where you were and what you were doing when you heard about the tragedy at Yarnell Hill. I sure do, and I will never forget it. We are dedicating our Summer Issue of Two More Chains to our 19 fallen Granite Mountain Hotshot Crew brothers who lost their lives on June 30, 2013, on the Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona. This tragic loss has shaken the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center The 2013 Granite Mountain Hotshots (LLC) team to our knees. We are struggling—just like you—with what we can do to assist the families and our fellow firefighters during such a “Our deepest sympathies to the families, friends, and coworkers of the difficult time. Granite Mountain IHC. We are the safety net of the wildland community Three LLC team members and we will continue to be there during these dark hours.” were able to attend the th The Wildland Firefighter Foundation July 9 memorial service www.wffoundation.org in Prescott Valley to Phone: 208-336-2996 show our support and How You Can Help pay our respects. May our fallen brothers The Wildland Firefighter Foundation’s main focus is to help families of firefighters killed in the line of duty rest in eternal peace. and to assist injured firefighters and their families. The link below provides info on how you can help this effort. Brit Rosso Lessons Learned bitly.com/wffdonate Center Manager 1 Granite Mountain Hot Shots “Esse Quam Videri” Darrell Willis, Division Chief of the Prescott Fire Department, informs us that the following is a letter written earlier this year by Eric Marsh, Superintendent of the Granite Mountain Hotshots, who perished with 18 of his fellow crewmembers on the Yarnell Hill Fire. -

Pima County Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Pima County Board of Supervisors City of Oro Valley City of Sahuarita Town of Marana City of South Tucson City of Tucson Altar Valley Conservation Alliance PIMA COUNTY Southern Arizona Buffelgrass Coordination Center COMMUNITY WILDFIRE Salt River Project PROTECTION PLAN Tucson Electric Power TRICO Electric Cooperative July 2013 Ajo-Gibson Volunteer Fire Department Arivaca Fire District Avra Valley Fire District Cascabel Volunteer Fire Department Corona de Tucson Fire Department Drexel Heights Fire District Elephant Head Volunteer Fire Department Golder Ranch Fire District Green Valley Fire District Helmet Peak Volunteer Fire Department Mescal-J6 Fire District Mount Lemmon Fire District Northwest Fire District Pascua Yaqui Tribe Fire Department Picture Rocks Fire District Rincon Valley Fire District Rural Metro Fire Department Sonoita-Elgin Fire Department South Tucson Fire Department Three Points Fire District Tucson Fire Department Why Fire Department Arizona State Forestry Division Bureau of Land Management Pascua Yaqui Tribe Coronado National Forest Saguaro National Park Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge DEDICATION The citizens of Pima County dedicate this Pima County Community Wildfire Protection Plan to the 19 members of the Prescott Fire Department's interagency Granite Mountain Hotshots who died protecting the community of Yarnell from the Yarnell Hill Fire on June 30, 2013, and to all the firefighters who have perished before them responding to fires in the wildland-urban interface. May this plan help reduce the number of -

Yarnell Hill Fire

Yarnell Hill Fire June 30, 2013 Serious Accident Investigation Report September 23, 2013 Cover Photo: Raising the United States and State of Arizona flags at the Granite Mountain crew’s deployment site. Courtesy of the Southwest Area Type 1 Incident Management Team. In Memory Of Andrew Sterling Ashcraft Robert E. Caldwell Travis Clay Carter Dustin James DeFord Christopher A. MacKenzie Eric S. Marsh Grant Quinn McKee Sean M. Misner Scott Daniel Norris Wade S. Parker John J. Percin, Jr. Anthony M. Rose Jesse James Steed Joe B. Thurston Travis Turbyfill William Howard ‘Billy’ Warneke Clayton Thomas Whitted Kevin J. Woyjeck Garret Zuppiger Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 1 The Investigation Process ............................................................................................... 5 Background ................................................................................................................... 8 Part One: Factual & Management Report ................................................................. 11 Narrative ...................................................................................................................... 11 Friday, 28 June 2013 ................................................................................................ 11 Saturday, 29 June 2013 ............................................................................................ 12 Sunday, 30 June 2013 ............................................................................................. -

2013-Jul-Aug.Pdf

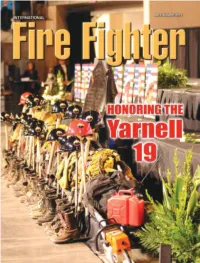

NOT ALL PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES GET SIGNING BONUSES. GLOBETURNOUTGEAR.COM ™ ® DuPont KEVLAR brand fi ber provides high-strength, GLOBE and designs are trademarks or registered trademarks of Globe Holding Company, LLC. DUPONT, KEVLAR permanent fl ame and thermal resistance, and proven durability. and designs are trademarks or registered trademarks of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company or its affi liates. 1:40 PM contents JULY/AUGUST 2013 JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF FIRE FIGHTERS/VOL. 96 NO. 3 FEATURES ON THE COVER Honoring the Yarnell 19 Public memorial service honors fallen hotshots ..............................18 INSIDE Wildfire season starts early The Battle Over Combining Police and Fire P. 20 Why the PSO model is a bad idea ..................................................10 General President’s Message Furloughs Leave Bases Less Safe Public Safety Before Politics ................................................5 Sequester threatens public safety on military bases ........................13 General Secretary-Treasurer’s Message IAFF Disaster Relief Back to Basics ....................................................................7 Tornados, flooding affect members..................................................14 Letters..............................................................................8 P. 23 Across the IAFF ..........................................................22 Always on the Frontline ............................................34 On the Road ................................................................36 -

First Responders' Role in Donation

First Responders’ Role in Donation Calvin Mosman’s Story n May 18, 2014 at 4:30 a.m., the hospital. Seconds later, she found her Lisa Mosman drove her little boy unconscious. husband, John Mosman, to the O When the Whetstone Fire Department airport. John was going to Germany on a business trip. Despite the early hour, his arrived, first responders assumed care of son Calvin and daughter Moxie insisted Calvin and were able to revive him. on accompanying him to the airport to However, on May 21, 2014, Calvin was say goodbye. declared brain-dead at Banner – University Before John departed, Calvin hugged him Medical Center Tucson. In honor of his tightly in the brisk morning air. John did giving spirit, Lisa and John chose to donate not know this was the last moment he Calvin’s organs, eyes and tissues. would see Calvin alive. Without the dedicated care provided by Calvin Mosman became an organ, eye and The next morning, Calvin suffered a first responders, Calvin may not have been tissue donor in May 2014 after a severe devastating asthma attack. Lisa rushed to able to share life through donation. asthma attack took his life. get dressed so she could take Calvin to Intubation and Documentation Steps taken by first responders are Clarity in documenting resuscitative “The work of first responders critical to ensuring the potential for efforts performed on a patient is also has a direct impact on whether organ, eye and tissue donation, should essential, should the possibility of donation is a possibility.” the patient pass away. -

For More Information Regarding the Arizona Fallen Firefighter Memorial Or the Arizona Firefighters & Emergency Paramedics Memorial Commission Go To

For more information regarding the Arizona Fallen Firefighter Memorial or the Arizona Firefighters & Emergency Paramedics Memorial Commission go to: www.azfirefightersmemorial.com ©2015 Arizona Firefighters & Emergency Paramedics Memorial Commission 2 3 4 5 To charge into burning buildings as others rush out, to brave the dangerous and unpredictable flames of wildfires, to arrive first at the scene of an emergency in a desperate bid to save lives of neighbors, friends and strangers – that takes a rare, selfless courage too often taken for granted. Arizona has a special and solemn gratitude for the sacrifices of these men and women. We’ve lost more than 119 firefighters and paramedics in the line of duty – including 19 heroic Granite Mountain Hot Shots taken at Yarnell Hill in 2013 in Arizona’s deadliest wildfire on record. We will never forget all of these men and women. They gave their lives to protect their communities, and we can never repay them. That’s why I’m proud they’ll be forever honored on the grounds of Arizona’s State Capitol. This spectacular memorial will remind us every day of our fallen, as well as the countless heroes among us who devote their daily lives to saving ours. They, along with their families and loved ones, are eternally in our thoughts and prayers. The Arizona Fallen Firefighter Memorial is a fitting tribute to the dedication, professionalism and nobility of all Arizona first responders. I encourage all Arizonans to visit our State Capitol and pay deserved tribute to these heroes. Doug Ducey 6 Governor - State of Arizona All Firefighters and First Responders are Heroes for What They do.