Bertha Hope-Booker Interviewed for Allegro, January 13, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazzweek with Airplay Data Powered by Jazzweek.Com • December 13, 2010 Volume 7, Number 3 • $7.95

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • December 13, 2010 Volume 7, Number 3 • $7.95 Jazz Album No. 1: The Clayton Brothers The Smooth Album No. 1: Dave Koz Hello New Song And Dance (ArtistShare) Tomorrow (Concord) World Music No. 1: AfroCubism AfroCubism Smooth Single No. 1: Dave Koz “Put The Top (Nonesuch) Down” (Concord) Jazz Album Chart .................... 3 Jazz Add Dates ...................... 7 Smooth Jazz Album Chart ............. 4 Jazz Radio Currents .................. 8 Smooth Singles Chart ................. 5 Jazz Radio Panel ................... 11 World Music Album Chart.............. 6 Smooth Jazz Current Tracks........... 13 Smooth Jazz Station Panel............ 14 Jazz Birthdays December 13 December 17 December 25 Sonny Greer (1895) Ray Noble (1903) Kid Ory (1890) Ben Tucker (1930) Sy Oliver (1910) Cab Calloway (1907) Reggie Johnson Born (1940) Sonny Red (1932) Chris Woods (1925) Mark Elf (1949) Walter Booker (1933) Bob James (1939) December 14 December 18 Ronnie Cuber (1941) Budd Johnson (1910) Fletcher Henderson (1897) December 26 Ted Buckner (1913) Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson (1917) Monty Budwig (1929) Clark Terry (1920) Harold Land (1928) John Scofield (1951) Cecil Payne (1922) Leo Smith (1941) Cassandra Wilson (1955) Phineas Newborn (1931) December 19 December 27 Jerome Cooper (1946) Bob Brookmeyer (1929) Bunk Johnson (1889) Dan Barrett (1955) Bobby Timmons (1935) Booty Wood (1919) December 15 December 20 Walter Norris (1931) Stan Kenton (1911) Larry Willis (1940) December 28 Billy Butler (1925) December -

Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950S and Early 1960S New World NW 275

Introspection: Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950s and early 1960s New World NW 275 In the contemporary world of platinum albums and music stations that have adopted limited programming (such as choosing from the Top Forty), even the most acclaimed jazz geniuses—the Armstrongs, Ellingtons, and Parkers—are neglected in terms of the amount of their music that gets heard. Acknowledgment by critics and historians works against neglect, of course, but is no guarantee that a musician will be heard either, just as a few records issued under someone’s name are not truly synonymous with attention. In this album we are concerned with musicians who have found it difficult—occasionally impossible—to record and publicly perform their own music. These six men, who by no means exhaust the legion of the neglected, are linked by the individuality and high quality of their conceptions, as well as by the tenaciousness of their struggle to maintain those conceptions in a world that at best has remained indifferent. Such perseverance in a hostile environment suggests the familiar melodramatic narrative of the suffering artist, and indeed these men have endured a disproportionate share of misfortunes and horrors. That four of the six are now dead indicates the severity of the struggle; the enduring strength of their music, however, is proof that none of these artists was ultimately defeated. Selecting the fifties and sixties as the focus for our investigation is hardly mandatory, for we might look back to earlier years and consider such players as Joe Smith (1902-1937), the supremely lyrical trumpeter who contributed so much to the music of Bessie Smith and Fletcher Henderson; or Dick Wilson (1911-1941), the promising tenor saxophonist featured with Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy; or Frankie Newton (1906-1954), whose unique muted-trumpet sound was overlooked during the swing era and whose leftist politics contributed to further neglect. -

BROWNIE the Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet

BROWNIE The Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet Dan Morgenstern Grammy Award for Best Album Notes 1990 Disc 1 1. DELILAH 8:04 Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: (V. Young) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 2. DARN THAT DREAM 4:02 Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (De Lange - V. Heusen) (ds) 3. PARISIAN THOROUGHFARE 7:16 (B. Powell) 4. JORDU 7:43 (D. Jordan) 5. SWEET CLIFFORD 6:40 (C. Brown) 6. SWEET CLIFFORD (CLIFFORD’S FANTASY)* 1:45 1~3: Los Angeles, August 2, 1954 (C. Brown) 7. I DON’T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANCE* 3:03 4~8: Los Angeles, August 3, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 8. I DON’ T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANC E 7:19 9~12: Los Angeles, August 5, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 9. STOMPIN’ AT TH E SAVOY 6:24 (Goodman - Sampson - Razaf - Webb) 10. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU 7:36 (C. Porter) 11. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* 8:29 * Previously released alternate take (C. Porter) 12. I’ LL STRING ALONG WITH YOU 4:10 (Warren - Dubin) Disc 2 1. JOY SPRING* 6:44 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: 2. JOY SPRING 6:49 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 3. MILDAMA* 3:33 (M. Roach) Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (ds) 4. MILDAMA* 3:22 (M. Roach) Los Angeles, August 6, 1954 5. MILDAMA* 3:55 (M. Roach) 6. -

Extensions of Remarks E41 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

January 9, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E41 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS KROEGER WINS FOOT LOCKER Following his first duty assignment with Ma- CELEBRATING THE LIFE OF JANE HIGH SCHOOL CROSS COUNTRY rine Corps Security Forces in Kings Bay, FAGERSTROM NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP Georgia, Corporal Dunham was assigned to Fourth Platoon, Kilo Company, Third Battalion, HON. BRIAN HIGGINS HON. LINCOLN DAVIS Regimental Combat Team 7, First Marine Divi- OF NEW YORK OF TENNESSEE sion. Having quickly proven himself as a capa- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ble and conscientious leader, Corporal IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Tuesday, January 9, 2007 Dunham was assigned as a Squad Leader Tuesday, January 9, 2007 and entrusted with the training, welfare, and Mr. LINCOLN DAVIS of Tennessee. Madam lives of nine American Sons. He soon earned Mr. HIGGINS. Madam Speaker, it is my dis- Speaker, it is not everyday a Member of Con- a reputation for his unwavering commitment to tinct honor to remember the life of a proud gress gets the opportunity to proclaim they his fellow Marines. He had a caring, respect- Chautauqua County leader. Jane Fagerstrom, have a national champion attending school in ful, and humane style of leadership and be- born April 1, 1927, to Floyd and Bertha Alden their district. I rise today to congratulate Kathy lieved above all in leadership by example. Nelson, passed away on January 6, 2006, at Kroeger, a student at Independence High the age of 79. She left behind a legacy for all School in Thompson Station, Tennessee, for On 14 April 2004, while conducting a recon- Chautauqua County residents to be proud of. -

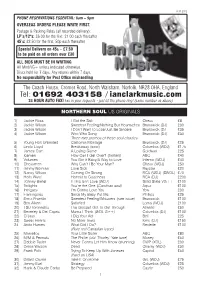

Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1

Clarky List 51_Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1 JULY 2012 PHONE RESERVATIONS ESSENTIAL : 8am – 9pm OVERSEAS ORDERS PLEASE WRITE FIRST. Postage & Packing Rates (all recorded delivery): LP’s/12"s: £6.00 for the first, £1.00 each thereafter 45’s: £2.50 for the first, 50p each thereafter Special Delivery on 45s – £7.50 to be paid on all orders over £30 ALL BIDS MUST BE IN WRITING All Mint/VG+ unless indicated otherwise. Discs held for 7 days. Any returns within 7 days. No responsibility for Post Office mis han dling The Coach House, Cromer Road, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0HA, England Tel: 01692 403158 / ianclarkmusic.com 24 HOUR AUTO FAX! Fax in your requests - just let the phone ring! (same number as above) NORTHERN SOUL US ORIGINALS 1) Jackie Ross I Got the Skill Chess £8 2) Jackie Wilson Sweetest Feeling/Nothing But Heartaches Brunswick (DJ) £30 3) Jackie Wilson I Don’t Want to Lose/Just Be Sincere Brunswick (DJ £35 4) Jackie Wilson Who Who Song Brunswick (DJ) £30 Three rare promos of these soul classics 5) Young Holt Unlimited California Montage Brunswick (DJ) £25 6) Linda Lloyd Breakaway (swol) Columbia (WDJ) £175 7) James Carr A Losing Game Goldwax £25 8) Icemen How Can I Get Over? (brilliant) ABC £40 9) Volumes You Got it Baby/A Way to Love Inferno (WDJ) £40 10) Chessmen Why Can’t I Be Your Man? Chess (WDJ) £50 11) Jimmy Norman Love Sick Raystar £20 12) Nancy Wilcox Coming On Strong RCA (WDJ) (SWOL) £70 13) Herb Ward Honest to Goodness RCA (DJ) £200 14) Johnny Bartel If This Isn’t Love (WDJ) Solid State VG++ £100 15) Twilights -

Drums • Bobby Bradford - Trumpet • James Newton - Flute • David Murray - Tenor Sax • Roberto Miranda - Bass

1975 May 17 - Stanley Crouch Black Music Infinity Outdoors, afternoon, color snapshots. • Stanley Crouch - drums • Bobby Bradford - trumpet • James Newton - flute • David Murray - tenor sax • Roberto Miranda - bass June or July - John Carter Ensemble at Rudolph's Fine Arts Center (owner Rudolph Porter)Rudolph's Fine Art Center, 3320 West 50th Street (50th at Crenshaw) • John Carter — soprano sax & clarinet • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums 1976 June 1 - John Fahey at The Lighthouse December 15 - WARNE MARSH PHOTO Shoot in his studio (a detached garage converted to a music studio) 1490 N. Mar Vista, Pasadena CA afternoon December 23 - Dexter Gordon at The Lighthouse 1976 June 21 – John Carter Ensemble at the Speakeasy, Santa Monica Blvd (just west of LaCienega) (first jazz photos with my new Fujica ST701 SLR camera) • John Carter — clarinet & soprano sax • Roberto Miranda — bass • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums • Melba Joyce — vocals (Bobby Bradford's first wife) June 26 - Art Ensemble of Chicago Studio Z, on Slauson in South Central L.A. (in those days we called the area Watts) 2nd-floor artists studio. AEC + John Carter, clarinet sat in (I recorded this on cassette) Rassul Siddik, trumpet June 24 - AEC played 3 nights June 24-26 artist David Hammond's Studio Z shots of visitors (didn't play) Bobby Bradford, Tylon Barea (drummer, graphic artist), Rudolph Porter July 2 - Frank Lowe Quartet Century City Playhouse. • Frank Lowe — tenor sax • Butch Morris - drums; bass? • James Newton — cornet, violin; • Tylon Barea -- flute, sitting in (guest) July 7 - John Lee Hooker Calif State University Fullerton • w/Ron Thompson, guitar August 7 - James Newton Quartet w/guest John Carter Century City Playhouse September 5 - opening show at The Little Big Horn, 34 N. -

Top 10 Albums Rhythm Section Players Should Listen to 1

Top 10 Albums Rhythm Section Players Should Listen To 1. Money Jungle by Duke Ellington Duke Ellington-Piano Charles Mingus-Bass Max Roach-Drums RELEASED IN 1963 Favorite Track: Caravan 2. Monk Plays Duke by Thelonious Monk Thelonious Monk- Piano Oscar Pettiford-Bass Kenny Clarke-Drums RELEASED IN 1956 Favorite Track: I Let A Song Out of My Heart 3. We Get Request by Oscar Peterson Trio Oscar Peterson-Piano Ray Brown-Bass Ed Thigpen-Drums RELEASED IN 1964 Favorite Track: Girl from Ipanema 4. Now He Sings, Now He Sobs by Chick Corea Chick Corea-Piano Miroslav Vitous-Bass Roy Haynes-Drums RELEASED IN 1968 Favorite Track: Matrix 5. We Three by Roy Haynes Phineas Newborn-Piano Paul Chambers-Bass Roy Haynes-Drums RELEASED IN 1958 Favorite Track(s): Sugar Ray & Reflections 6. Soul Station by Hank Mobley Hank Mobley-Tenor Sax Wynton Kelly-Piano Paul Chambers-Bass Art Blakey-Drums RELEASED IN 1960 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM! 7. Free for All by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Freddie Hubbard-Trumpet Curtis Fuller-Trombone Wayne Shorter-Tenor Saxophone Cedar Walton-Piano Reggie Workman-Bass Art Blakey-Drums RELEASED IN 1964 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM 8. Live at the IT Club by Thelonious Monk Charlie Rouse-Alto Saxophone Thelonious Monk-Piano Larry Gales-Bass Ben Riley-Drums RECORDED IN 1964; RELEASED IN 1988 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM 9. Clifford Brown & Max Roach by Clifford Brown & Max Roach Clifford Brown-Trumpet Harold Land-Tenor Saxophone Richie Powell-Piano George Morrow-Bass Max Roach-Drums RELEASED IN 1954 Favorite Track(s): Jordu, Daahoud, and Joy Spring 10. -

HISTORY of JAZZ II – 1St

HISTORY OF JAZZ II MUZ2339W –Semester One Class Notes By Prof M.J. Rossi Hard Bop Hard bop – term applied to hard driving, intense style of jazz in the 1950s- 60s. Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Cannonball Adderley, Sonny Rollins extended to encompass the music of Miles Davis, J.J. Johnson, Art Farmer – Benny Golson. Dark weighty textures, soulful inflections, blues like melodic figures, chord progressions borrowed form the black church, louder more interactive drumming, more facile bass playing, drew less on forms of the previous period. Most players were African-Americans and came out of Philadelphia and Detroit. Best remembered tunes: Senor Blues, Song for My Father – Horace Silver Work Song – Nat Adderely, Mercy, Mercy, Mercy – Joe Zawinul The Sidewinder – Lee Morgan Watermelon Man – Herbie Hancock The Birth of Hard Bop (Jazz: The First Century, pgs 115-117) The cool school had offered a reaction to bebop, but in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit, the jazz of the 1950s derived primarily from bebop to become the style called hard bop. The Miles Davis recordings of “Four” (1954) and “Walkin’ (1954) suggest the arrival of hard bop, the real parents were Art Blakey and Horace Silver. In the summer of 1954 both formed a cooperative quintet, the Jazz Messengers, and in 1955 they recorded a jubilant shout in the form of the 16-bar blues “The Preacher”, composed by Silver, as Goldberg states, “The reaction to the reaction had taken place.”. To be sure, the hard boppers were responding to cool’s constraints with their emotionalism. But they were also reacting to the calcinations of bebop. -

Ebook Download the Mccoy Tyner Collection

THE MCCOY TYNER COLLECTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK McCoy Tyner | 120 pages | 01 Nov 1992 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9780793507474 | English | Milwaukee, United States The Mccoy Tyner Collection PDF Book Similar Artists See All. There's magic in the air, or at the very least a common ground of shared values that makes this combination of two great musicians turn everything golden. That's not to say their progressive ideas are completely harnessed, but this recording is something lovers of dinner music or late-night romantic trysts will equally appreciate. McCoy Tyner. Extensions - McCoy Tyner. Tyner died on March 6, at his home in New Jersey. They sound empathetic, as if they've played many times before, yet there are enough sparks to signal that they're still unsure of what the other will play. Very highly recommended. Albums Live Albums Compilations. Cart 0. If I Were a Bell. On this excellent set, McCoy Tyner had the opportunity for the first time to head a larger group. McCoy later said, Bud and Richie Powell moved into my neighborhood. He also befriended saxophonist John Coltrane, then a member of trumpeter Miles Davis' band. A flow of adventurous, eclectic albums followed throughout the decade, many featuring his quartet with saxophonist Azar Lawrence, including 's Song for My Lady, 's Enlightenment, and 's Atlantis. McCoy Tyner Trio. See the album. Throughout his career, Tyner continued to push himself, arranging for his big band and releasing Grammy-winning albums with 's Blues for Coltrane: A Tribute to John Coltrane and 's The Turning Point. However, after six months with the Jazztet, he left to join Coltrane's soon-to-be classic quartet with bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones. -

Spilleliste: Åtti Deilige År Med Blue Note Foredrag Oslo Jazz Circle, 14

Spilleliste: Åtti deilige år med Blue Note Foredrag Oslo Jazz Circle, 14. januar 2020 av Johan Hauknes Preludium BLP 1515/16 Jutta Hipp At The Hickory House /1956 Hickory House, NYC, April 5, 1956 Jutta Hipp, piano / Peter Ind, bass / Ed Thigpen, drums Volume 1: Take Me In Your Arms / Dear Old Stockholm / Billie's Bounce / I'll Remember April / Lady Bird / Mad About The Boy / Ain't Misbehavin' / These Foolish Things / Jeepers Creepers / The Moon Was Yellow Del I Forhistorien Meade Lux Lewis, Albert Ammons & Pete Johnson Jumpin' Blues From Spiritals to Swing, Carnegie Hall, NYC, December 23, 1938 BN 4 Albert Ammons - Chicago In Mind / Meade "Lux" Lewis, Albert Ammons - Two And Fews Albert Ammons Chicago in Mind probably WMGM Radio Station, NYC, January 6, 1939 BN 6 Port of Harlem Seven - Pounding Heart Blues / Sidney Bechet - Summertime 1939 Sidney Bechet, soprano sax; Meade "Lux" Lewis, piano; Teddy Bunn, guitar; Johnny Williams, bass; Sidney Catlett, drums Summertime probably WMGM Radio Station, NYC, June 8, 1939 Del II 1500-serien BLP 1517 Patterns in Jazz /1956 Gil Mellé, baritone sax; Eddie Bert [Edward Bertolatus], trombone; Joe Cinderella, guitar; Oscar Pettiford, bass; Ed Thigpen, drums The Set Break Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, April 1, 1956 BLP 1521/22 Art Blakey Quintet: A Night at Birdland Clifford Brown, trumpet; Lou Donaldson, alto sax; Horace Silver, piano; Curly Russell, bass; Art Blakey, drums A Night in Tunisia (Dizzy Gillespie) Birdland, NYC, February 21, 1954 BLP 1523 Introducing Kenny Burrell /1956 Tommy Flanagan, -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert.