The Challenge of Anonymous and Ephemeral Social Media: Reflective Research Methodologies & Student-User Composing Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Many Shades of Anonymity: Characterizing Anonymous Social Media Content

Proceedings of the Ninth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media The Many Shades of Anonymity: Characterizing Anonymous Social Media Content Denzil Correay, Leandro Araújo Silvaz, Mainack Mondaly, Fabrício Benevenutoz, Krishna P. Gummadiy y Max Planck Institute for Software Systems (MPI-SWS), Germany z Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil Abstract While anonymous online forums have been in existence since the early days of the Internet, in the past, such forums Recently, there has been a significant increase in the popu- larity of anonymous social media sites like Whisper and Se- were often devoted to certain sensitive topics or issues. In cret. Unlike traditional social media sites like Facebook and addition, its user population was relatively small and limited Twitter, posts on anonymous social media sites are not as- to technically sophisticated users with specific concerns or sociated with well-defined user identities or profiles. In this requirements to be anonymous. On the other hand, anony- study, our goals are two-fold: (i) to understand the nature mous social media sites like Whisper1 and Secret2 provide a (sensitivity, types) of content posted on anonymous social generic and easy-to-use platform for lay users to post their media sites and (ii) to investigate the differences between thoughts in relative anonymity. Thus, the advent and rapidly content posted on anonymous and non-anonymous social me- growing adoption of these sites provide us with an oppor- dia sites like Twitter. To this end, we gather and analyze ex- tunity for the first time to investigate how large user popu- tensive content traces from Whisper (anonymous) and Twitter lations make use of an anonymous public platform to post (non-anonymous) social media sites. -

Social Construction of Privacy: Reddit Case Study

Social Construction of Privacy: Reddit Case Study December 13, 2020 A Thesis Prospectus Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science University of Virginia ² Charlottesville, Virginia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Bachelor of Science, School of Engineering Rajiv Sarvepalli 1 1 INTRODUCTION In the technological age of today, privacy becomes a more and more valuable commod- ity. With so many companies that live off the idea that information is money, it becomes increasingly concerning the amount of an individual’s information that is public. It is public in every sense of the word, not just to a group of people, but to the whole world. Consider the constant data scandals that plague our technological world. Whether it is Facebook, Google, or governments, someone is always getting caught selling, collecting, or losing data that many consider infringes on their privacy. Therefore, as stewards of these technologies, we must develop preemptive ways of protecting the privacy of the individual in an information-based world focused on the collective. The heterogeneous nature of society, especially with respect to privacy, makes the perspective vary greatly from person to person. This study shall focus on Reddit, an anonymous social media since individuals within anonymous social media communities tend to view anonymity as some form of privacy and therefore tend to care about in some manner about privacy. In order to understand the perspective and definitions of privacy, privacy needs to be analyzed in the context of a society. The conundrum of our information society is the constant complaints of lack of privacy, yet no privacy-invasive companies change their conduct. -

The Public Square Project

THE PUBLIC SQUARE PROJECT The case for building public digital infrastructure to support our community and our democracy With majority support from Australians on curbing Facebook’s influence and role on our civic spaces, it is time to create an alternative social network that serves the public interest Research report Jordan Guiao Peter Lewis CONTENTS 2 // SUMMARY 3 // INTRODUCTION 5 // REIMAGINING THE PUBLIC SQUARE 10 // A NEW PUBLIC DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE 12 // CONSIDERATIONS IN BUILDING PUBLIC DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE 17 // TOWARDS THE FUTURE 19 // CONCLUSION 20 // APPENDIX — ALTERNATE SOCIAL NETWORKS OVER TIME The public square is a place where citizens come together, exchange ideas and mediate differences. It has its origins in the physical town square, where a community can gather in a central and open public space. As towns grew and technology progressed, the public square has become an anchor of democracy, with civic features like public broadcasting creating a space between the commercial, the personal and the government that helps anchor communities in shared understanding. 1 | SUMMARY In recent times, online platforms like Facebook In re-imagining a new public square, this paper have usurped core aspects of what we expect from proposes an incremental evolution of the Australian a public square. However, Facebook’s surveillance public broadcaster, centred around principles business model and engagement-at-all-costs developed by John Reith, the creator of public algorithm is designed to promote commercial rather broadcasting, of an independent, but publicly-funded than civic objectives, creating a more divided and entity with a remit to ‘inform, educate and entertain’ distorted public discourse. -

Characterizing Anonymous Social Media Content

The Many Shades of Anonymity: Characterizing Anonymous Social Media Content Denzil Correa†, Leandro Araújo Silva‡, Mainack Mondal†, Fabrício Benevenuto‡, Krishna P. Gummadi† † Max Planck Institute for Software Systems (MPI-SWS), Germany ‡ Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil Abstract While anonymous online forums have been in existence since the early days of the Internet, in the past, such forums Recently, there has been a significant increase in the popu- larity of anonymous social media sites like Whisper and Se- were often devoted to certain sensitive topics or issues. In cret. Unlike traditional social media sites like Facebook and addition, its user population was relatively small and limited Twitter, posts on anonymous social media sites are not as- to technically sophisticated users with specific concerns or sociated with well-defined user identities or profiles. In this requirements to be anonymous. On the other hand, anony- study, our goals are two-fold: (i) to understand the nature mous social media sites like Whisper1 and Secret2 provide a (sensitivity, types) of content posted on anonymous social generic and easy-to-use platform for lay users to post their media sites and (ii) to investigate the differences between thoughts in relative anonymity. Thus, the advent and rapidly content posted on anonymous and non-anonymous social me- growing adoption of these sites provide us with an oppor- dia sites like Twitter. To this end, we gather and analyze ex- tunity for the first time to investigate how large user popu- tensive content traces from Whisper (anonymous) and Twitter lations make use of an anonymous public platform to post (non-anonymous) social media sites. -

The Many Shades of Anonymity: Characterizing Anonymous Social Media Content

The Many Shades of Anonymity: Characterizing Anonymous Social Media Content Denzil Correay, Leandro Araújo Silvaz, Mainack Mondaly, Fabrício Benevenutoz, Krishna P. Gummadiy y Max Planck Institute for Software Systems (MPI-SWS), Germany z Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil Abstract While anonymous online forums have been in existence since the early days of the Internet, in the past, such forums Recently, there has been a significant increase in the popu- larity of anonymous social media sites like Whisper and Se- were often devoted to certain sensitive topics or issues. In cret. Unlike traditional social media sites like Facebook and addition, its user population was relatively small and limited Twitter, posts on anonymous social media sites are not as- to technically sophisticated users with specific concerns or sociated with well-defined user identities or profiles. In this requirements to be anonymous. On the other hand, anony- study, our goals are two-fold: (i) to understand the nature mous social media sites like Whisper1 and Secret2 provide a (sensitivity, types) of content posted on anonymous social generic and easy-to-use platform for lay users to post their media sites and (ii) to investigate the differences between thoughts in relative anonymity. Thus, the advent and rapidly content posted on anonymous and non-anonymous social me- growing adoption of these sites provide us with an oppor- dia sites like Twitter. To this end, we gather and analyze ex- tunity for the first time to investigate how large user popu- tensive content traces from Whisper (anonymous) and Twitter lations make use of an anonymous public platform to post (non-anonymous) social media sites. -

Unmasking the Teen Cyberbully: a First Amendment-Compliant Approach to Protecting Child Victims of Anonymous, School-Related Internet Harassment Benjamin A

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals November 2017 Unmasking the Teen Cyberbully: A First Amendment-Compliant Approach to Protecting Child Victims of Anonymous, School-Related Internet Harassment Benjamin A. Holden Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Holden, Benjamin A. (2017) "Unmasking the Teen Cyberbully: A First Amendment-Compliant Approach to Protecting Child Victims of Anonymous, School-Related Internet Harassment," Akron Law Review: Vol. 51 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol51/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Holden: Unmasking the Teen Cyberbully UNMASKING THE TEEN CYBERBULLY: A FIRST AMENDMENT-COMPLIANT APPROACH TO PROTECTING CHILD VICTIMS OF ANONYMOUS, SCHOOL-RELATED INTERNET HARASSMENT By: Benjamin A. Holden* I. Introduction and Overview ............................................ 2 II. Minors and The First Amendment ................................. 9 A. The First Amendment and Minors Generally ....... 10 B. The First Amendment and The Student Speech Cases ..................................................................... 10 C. The First Amendment and The Child Protection Cases ..................................................................... 12 1. -

The Virtual Bathroom Stall: Solving the Headache of Geo-Based Anonymous Message Applications on University Campuses

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\85-3\GWN305.txt unknown Seq: 1 7-JUL-17 8:22 NOTE The Virtual Bathroom Stall: Solving the Headache of Geo-Based Anonymous Message Applications on University Campuses Thomas C. Gallagher, Jr.* ABSTRACT Since its launch in late 2013, Yik Yak, a location-based application that permits users to post on local, virtual message boards targeted at university campuses, has become a massive headache for universities who are responsi- ble, under Department of Education guidelines, for maintaining a safe envi- ronment for their students. These message boards have become a breeding ground for personal attacks, sexual harassment, bigotry, and threats of mass violence, which have caused huge disruptions to educational environments. Yik Yak, however, is not responsible for the messages being posted; it is re- sponsible only for creating and placing virtual bulletin boards on college cam- puses, which the institutions have no ability to regulate. Through guidance letters issued over the last five years, the Department of Education has warned universities that they may be responsible for adequately responding to inci- dents and environments of harassment that occur on their campuses, regard- less of the medium through which the harassment occurs. Because Yik Yak’s Global Positioning System (“GPS”) located virtual message boards are no different than if someone walked onto the school grounds and placed a mes- sage board on the physical campus without the school’s permission, this Note proposes universities use the traditional property law action of trespass to ex- clude the Yik Yak application from campuses. * J.D., 2017, The George Washington University Law School. -

Campus Safety V. Freedom of Speech: an Evaluation of University Responses to Problematic Speech on Anonymous Social Media Susan Dumont

Journal of Business & Technology Law Volume 11 | Issue 2 Article 7 Campus Safety v. Freedom of Speech: An Evaluation of University Responses to Problematic Speech on Anonymous Social Media Susan DuMont Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jbtl Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Susan DuMont, Campus Safety v. Freedom of Speech: An Evaluation of University Responses to Problematic Speech on Anonymous Social Media, 11 J. Bus. & Tech. L. 239 (2016) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jbtl/vol11/iss2/7 This Notes & Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Business & Technology Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Susan DuMont* Campus Safety v. Freedom of Speech: An Evaluation of University Responses to Problematic Speech on Anonymous Social Media Introduction Social media impacts how college students interact, and universities are struggling with the challenges presented by problematic speech on these sites. Platforms that encourage unidentified posting, such as Yik Yak and former gossip site JuicyCampus.com, significantly increase the potential for real harm through problematic speech, including hate speech, threats of violence, sexual harassment, and other forms of damaging, anonymous speech.1 University administrators are forced to evaluate options for responding to problematic speech on anonymous social media sites.2 Given the current culture of treating the internet as the “Wild West,” it is understandable why universities may choose to ignore the sites and why response has been limited.3 On the other end of © 2016 Susan DuMont * J.D., University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, 2016; M.A., University of Delaware, 2010; B.A., Lake Forest College, 2007. -

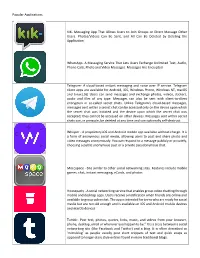

Popular Applications KIK- Messaging App That Allows Users to Join Groups Or Direct Message Other Users. Photos/Videos Can Be

Popular Applications KIK- Messaging App That Allows Users to Join Groups or Direct Message Other Users. Photos/Videos Can Be Sent, and All Can Be Deleted by Deleting the Application. WhatsApp- A Messaging Service That Lets Users Exchange Unlimited Text, Audio, Phone Calls, Photo and Video Messages. Messages Are Encrypted Telegram- A cloud-based instant messaging and voice over IP service. Telegram client apps are available for Android, iOS, Windows Phone, Windows NT, macOS and Linux.[16] Users can send messages and exchange photos, videos, stickers, audio and files of any type. Messages can also be sent with client-to-client encryption in so-called secret chats. Unlike Telegram's cloud-based messages, messages sent within a secret chat can be accessed only on the device upon which the secret chat was initiated and the device upon which the secret chat was accepted; they cannot be accessed on other devices. Messages sent within secret chats can, in principle, be deleted at any time and can optionally self-destruct. Whisper - A proprietary iOS and Android mobile app available without charge. It is a form of anonymous social media, allowing users to post and share photo and video messages anonymously. You can respond to a message publicly or privately, choosing a public anonymous post or a private pseudonymous chat. Mocospace - Site similar to other social networking sites. Features include mobile games, chat, instant messaging, eCards, and photos Houseparty - A social networking service that enables group video chatting through mobile and desktop apps. Users receive a notification when friends are online and available to group video chat. -

Social Media and Democracy : the State of the Field, Prospects for Reform

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.19, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:20:02, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/E79E2BBF03C18C3A56A5CC393698F117 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.19, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:20:02, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/E79E2BBF03C18C3A56A5CC393698F117 Social Media and Democracy Over the last five years, widespread concern about the effects of social media on democracy has led to an explosion in research from different disciplines and corners of academia. This book is the first of its kind to take stock of this emerging multi-disciplinary field by synthesizing what we know, identifying what we do not know and obstacles to future research, and charting a course for the future inquiry. Chapters by leading scholars cover major topics – from disinformation to hate speech to political advertising – and situate recent developments in the context of key policy questions. In addition, the book canvasses existing reform proposals in order to address widely perceived threats that social media poses to democracy. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. Nathaniel Persily is the James B. McClatchy Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and the Co-Director of the Stanford Cyber Policy Center and Stanford Project on Democracy and the Internet. His scholarship focuses on the law and technology of democracy. -

Understanding Social Media: Tweets, Yaks, and the Social Web in College Health

Understanding Social Media: Tweets, Yaks, and the Social Web in College Health #ACHA2016 Tammy Ostroski, DNP, FNP In collaboration with: Rita Wermers, MSN, ANP James Wermers, MS OVERVIEW PART I ● Describe the current state of social media use in health PART II ● Explain the need for college health professionals to critically evaluate and deploy social media PART III ● Discuss how at least 4 different social media platforms can be engaged and deployed by college health professionals PART I SOCIAL MEDIA BOYD AND ELLISON (2008) ● [W]eb-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. (p. 211). RECENT EXPANSION ● Movement away from individual profiles and towards collaborative identity EVOLUTION WEB 1.0 ● Static ● "Archive of data" ● Taxonomy WEB 2.0 ● Collaborative ● "Transparent mechanism" ● Folksonomy WEB 2.5 ● Collectivist IN HEALTH US CONSUMERS ● Utilize platforms like WebMD, Mayo Clinic and Google for health information (Web 1.0) ● Social media (Web 2.0) consumption continues to increase ● New platforms HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS ● Case studies demonstrating traditional forms of efficacy. ● Ensure access to high quality information ● Goal to “empower” patients - Health Promotion ● Often see pitfalls rather than opportunities IN HEALTH (2) COLLEGE STUDENTS ● Utilize social media and social networks to guide personal health behaviors ● Targeted as early adopters COLLEGE HEALTH PROVIDERS ● Share many of the concerns non-college counterparts ● Seek to meet the unique needs of college students ● Balance between use of innovated technologies and risks related to patient privacy PART II LIT. -

Social Media

Social Media Social media has grown into an entrenched part of many middle school students’ daily lives. While the explosion of social media apps has many positive outcomes that increase communication and provide a mechanism for both young and old to feel connected, it has also negatively increased venues for teasing, ridicule and bullying to occur. Recently, we have noticed and heard from both students and parents that they are observing a higher level than usual of mean behavior occurring on social media. Student Council members have reported that mean comments tend to go in cycles usually linked to an issue or even that occurred outside of school. We wanted to share with parents what occurs here at school to educate our students and to address issues as they arise or impact the school learning environment. The topic of digital citizenship is taught in multiple courses. Social media is specifically covered in our health curriculum. Additionally, we began the year with a presentation from a representative, Miracruz Lora, from the Essex County District Attorney Kevin Burke’s office; in January the Tri- Town Council presented the film Screenagers followed by a panel discussion by local school and community members. Our 7th grade students also had an opportunity to view the movie and discuss the impacts of it in health class. We encourage any adult that views a mean situation occurring on their child’s social media to take a screen shot and report it to Mr. Monagle, our Assistant Principal. We can’t view much of what takes place on social media, so any evidence that allows us to view the comments is helpful to an investigation.