Modern Painters Autumn 2002 Pp. 112-117 Emin for Real What Does

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anya Gallaccio

ANYA GALLACCIO Born Paisley, Scotland 1963 Lives London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom 1988 Goldsmiths' College, University of London, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 NOW, The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland Stroke, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2018 dreamed about the flowers that hide from the light, Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland, United Kingdom All the rest is silence, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom 2017 Beautiful Minds, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2015 Silas Marder Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, San Diego, CA 2014 Aldeburgh Music, Snape Maltings, Saxmundham, Suffolk, United Kingdom Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2013 ArtPace, San Antonio, TX 2011 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom Annet Gelink, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland, Kilmarnock, United Kingdom Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2009 So Blue Coat, Liverpool, United Kingdom 2008 Camden Art Centre, London, United Kingdom 2007 Three Sheets to the wind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2006 Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil One art, Sculpture Center, New York, NY 2005 The Look of Things, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA Silver Seed, Mount Stuart Trust, Isle of Bute, Scotland 2004 Love is Only a Feeling, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2003 Love is only a feeling, Turner Prize Exhibition, -

Who Owns the Art World? an Online Panel Discussion with Hayley Newman, Morgan Quaintance and Richard Parry. This Short Panel

A DACS panel discussion, 14 March 2018 Who Owns the Art World? An online panel discussion with Hayley Newman, Morgan Quaintance and Richard Parry. This short panel debate took place during DACS’ Annual Strategy Day, as we thought about the context in which artists are currently working and how best DACS could best support artists and artists’ estates in the future. The Panel Mark Waugh (Chair) is the Business Development Director at DACS. Hayley Newman, Artist and Reader of Fine Art, Slade School of Fine Art, UCL. Morgan Quaintance, writer, musician, broadcaster and curator. Richard Parry, Artist. Mark Waugh (MW): Welcome, and we’re live again at DACS, this time from RIBA, and we’re live with a specific question, it’s quite a simple question – “Who Owns the Art World?” And to answer that, what we’re going to have three presentations, one from Richard Parry, one from Hayley Newman and one from Morgan Quaintance. They come from very particular positions and I think you’ll be able to understand what those positions are after the presentations. Essentially, all three of them share a discourtesy of concern with that question of ownership - and not only the ownership of the art world in a conceptual and a material sense - but also in what the role and agency of the artist is, and indeed, art is, in that context. And we’re asking that in the context of DACS as an organisation which has a 30-year history of thinking about what artists can do to empower themselves and support each other. -

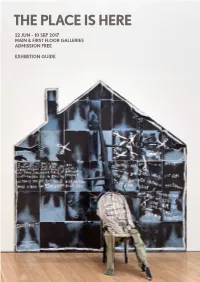

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

My Article in the Last Issue of Finch's Quarterly About the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition Achieved a Very Modest Degree

Hungary for Culture Charles Saumarez Smith takes issue with the line of Brian (Sewell) and looks forward to the Royal Academy’s Treasures from Budapest exhibition My article in the last issue of Finch’s Quarterly about the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition achieved a modest degree of fame by being quoted in Brian Sewell’s review of this year’s exhibition in the Evening Standard: As its chief executive put it in the current edition of a journal of which he is arts editor, the Academy holds “the 18th-century view that the best judges of art are not the critics but the public. Critics may sneer, but the public continues to enjoy the Summer Exhibition precisely because it gives them an opportunity to make up their own minds about what to like.” Sewell went on to say: The public can make up its mind about fish and chips and jellied eels, but to put it in charge of the kitchens of The Ritz would not be wise. And I am less sure that Charles Saumarez Smith’s contempt for critics was widely held anywhere in Europe in the 18th century, the Age of Reason, when the Enlightenment held sway; and even if it were, then the public to which he refers was not the ancestor of some bloke on the Clapham bendy-bus, but an educated gentleman with the benefits of private tutoring, Eton, Oxbridge and the Grand Tour, as ready with a Greek or Latin tag as our beloved Boris Johnson. The chief executive will find little of that background among the old biddies from Berkshire up for the day. -

Conrad Shawcross

CONRAD SHAWCROSS Born 1977 in London, UK Lives and works in London, UK Education 2001 MFA, Slade School of Art, University College, London, UK 1999 BA (Hons), Fine Art, Ruskin School of Art, Oxford, UK 1996 Foundation, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK Permanent Commissions 2022 Manifold 5:4, Crossrail Art Programme, Liverpool Street station, Elizabeth line, London, UK 2020 Schism Pavilion, Château la Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, France Pioneering Places, Ramsgate Royal Harbour, Ramsgate, UK 2019 Bicameral, Chelsea Barracks, curated by Futurecity, London, UK 2018 Exploded Paradigm, Comcast Technology Centre, Philadelphia, USA 2017 Beijing Canopy, Guo Rui Square, Beijing, China 2016 The Optic Cloak, The Energy Centre Greenwich Peninsula, curated by Futurecity, London, UK Paradigm, Francis Crick Institute, curated by Artwise, London, UK 2015 Three Perpetual Chords, Dulwich Park, curated and managed by the Contemporary Art Society for Southwark Council, London, UK 2012 Canopy Study, 123 Victoria Street, London, UK 2010 Fraction (9:8), Sadler Building, Oxford Science Park, curated and managed by Modus Operandi, Oxford, UK 2009 Axiom (Tower), Ministry of Justice, London, UK 2007 Space Trumpet, Unilever House, London, UK Solo Exhibitions 2020 Conrad Shawcross, an extended reality (XR) exhibition on Vortic Collect, Victoria Miro, London, UK Escalations, Château la Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, France Celebrating 800 years of Spirit and Endeavour, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, -

REVISED 4/27/2013 VERTIGINOUS ACEDIE, CIRCA 2013 the Preternatural Beauty and Equipoise of the Post-War Alexander Calder Mobiles

REVISED 4/27/2013 VERTIGINOUS ACEDIE, CIRCA 2013 The preternatural beauty and equipoise of the post-war Alexander Calder mobiles at Pace Gallery, Burlington Gardens, London, are more than offset/countered by the vertiginous acedie of the exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, Sloan Square, London, entitled “Gaiety is the Most Outstanding Feature of the Soviet Union: New Art from Russia.” Foremost in the latter instance is the series “The Neighbors” by Vikenti Nilin (born 1971). This series of ten images, all black-and-white giclée prints of the exact same size (165 x 110 cm.), is absolutely stunning – and chilling. Image (left) – Vikenti Nilin, “The Neighbors,” Saatchi Gallery, Sloan Square, London One needs to walk the length of Green Park, Hyde Park, and Kensington Gardens to properly prepare oneself for Calder (“Calder After the War”) versus the new Russian photography at Saatchi. (In preparation, one could even stop at the Natural History Museum in Knightsbridge for “Genesis,” semi-objective documentary photography by Sebastião Salgado, if crowds and entrance fees are acceptable.) The Calder mobiles are all installed on two floors in a classic, modernist white gallery at the north end of the Royal Academy, the whiteness of the spaces a tribute to the extreme austerities of the Calder mobiles and stabiles – the path to abstraction fully developed by 1945, the works shown covering the years 1945 to 1949. Curiously or not, Calder’s ascendance also coincides with the slow decline of the modernist avant-garde, which by 1927 was more or less over. This is a contentious issue, but it is more than borne out by the commoditization of modern art well underway by the mid- 1920s and the peculiar turn by Joan Miró into the repetition of his previously anarchic canon principally for the emergent modernist art market – a similar practice that beset Moholy-Nagy, Kandinsky, and others, primarily while in Germany. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

Art REVOLUTIONARIES Six Years Ago, Two Formidable, Fashionable Women Launched a New Enterprise

Art rEVOLUtIONArIES SIx yEArS AgO, twO fOrmIdAbLE, fAShIONAbLE wOmEN LAUNchEd A NEw ENtErprISE. thEIr mISSION wAS tO trANSfOrm thE wAy wE SUppOrt thE ArtS. thEIr OUtSEt/ frIEzE Art fAIr fUNd brOUght tOgEthEr pAtrONS, gALLErIStS, cUrAtOrS, thE wOrLd’S grEAtESt cONtEmpOrAry Art fAIr ANd thE tAtE IN A whIrLwINd Of fUNdrAISINg, tOUrS ANd pArtIES, thE LIkES Of whIch hAd NEVEr bEEN SEEN bEfOrE. hErE, fOr thE fIrSt tImE, IS thEIr INSIdE StOry. just a decade ago, the support mechanism for young artists in Britain was across the globe, and purchase it for the Tate collection, with the Outset funds. almost non-existent. Government funding for purchases of contemporary art It was a winner all round. Artists who might never have been recognised had all but dried up. There was a handful of collectors but a paucity of by the Tate were suddenly propelled into recognition; the national collection patronage. Moreover, patronage was often an unrewarding experience, both acquired work it would never otherwise have afforded. for the donor and for the recipient institution. Mechanisms were brittle and But the masterstroke of founders Gertler and Peel was that they made it old-fashioned. Artists were caught in the middle. all fun. Patrons were whisked on tours of galleries around the world or to Then two bright, brisk women – Candida Gertler and Yana Peel – marched drink champagne with artists; galleries were persuaded to hold parties into the picture. They knew about art; they had broad social contacts across a featuring collections of work including those by (gasp) artists tied to other new generation of young wealthy; and they had a plan. -

A Brief History of the Arts Catalyst

A Brief History of The Arts Catalyst 1 Introduction This small publication marks the 20th anniversary year of The Arts Catalyst. It celebrates some of the 120 artists’ projects that we have commissioned over those two decades. Based in London, The Arts Catalyst is one of Our new commissions, exhibitions the UK’s most distinctive arts organisations, and events in 2013 attracted over distinguished by ambitious artists’ projects that engage with the ideas and impact of science. We 57,000 UK visitors. are acknowledged internationally as a pioneer in this field and a leader in experimental art, known In 2013 our previous commissions for our curatorial flair, scale of ambition, and were internationally presented to a critical acuity. For most of our 20 years, the reach of around 30,000 people. programme has been curated and produced by the (founding) director with curator Rob La Frenais, We have facilitated projects and producer Gillean Dickie, and The Arts Catalyst staff presented our commissions in 27 team and associates. countries and all continents, including at major art events such as Our primary focus is new artists’ commissions, Venice Biennale and dOCUMEntA. presented as exhibitions, events and participatory projects, that are accessible, stimulating and artistically relevant. We aim to produce provocative, Our projects receive widespread playful, risk-taking projects that spark dynamic national and international media conversations about our changing world. This is coverage, reaching millions of people. underpinned by research and dialogue between In the last year we had features in The artists and world-class scientists and researchers. Guardian, The Times, Financial Times, Time Out, Wall Street Journal, Wired, The Arts Catalyst has a deep commitment to artists New Scientist, Art Monthly, Blueprint, and artistic process. -

THBT Social Disgust Is Legitimate Grounds for Restriction of Artistic Expression

Published on idebate.org (http://idebate.org) Home > THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression The history of art is full of pieces which, at various points in time, have caused controversy, or sparked social disgust. The works most likely to provoke disgust are those that break taboos surrounding death, religion and sexual norms. Often, the debate around whether a piece is too ‘disgusting’ is interwoven with debate about whether that piece actually constitutes a work of art: people seem more willing to accept taboo-breaking pieces if they are within a clearly ‘artistic’ context (compare, for example, reactions to Michelangelo’s David with reactions to nudity elsewhere in society). As a consequence, the debate on the acceptability of shocking pieces has been tied up, at least in recent times, with the debate surrounding the acceptability of ‘conceptual art’ as art at all. Conceptual art1 is that which places an idea or concept (rather than visual effect) at the centre of the work. Marchel Duchamp is ordinarily considered to have begun the march towards acceptance of conceptual art, with his most famous piece, Fountain, a urinal signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt”. It is popularly associated with the Turner Prize and the Young British Artists. This debate has a degree of scope with regards to the extent of the restriction of artistic expression that might be being considered here. Possible restrictions include: limiting display of some pieces of art to private collections only; withdrawing public funding (e.g. -

Evening Auction Realised £9,264,000 / $12,302,590 / €10,848,145 to Continue George Michael’S Philanthropic Work

MEDIA ALERT | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE R E L E A S E | 1 4 M A R C H 2 0 1 9 EVENING AUCTION REALISED £9,264,000 / $12,302,590 / €10,848,145 TO CONTINUE GEORGE MICHAEL’S PHILANTHROPIC WORK THE GEORGE MICHAEL COLLECTION 100% SOLD 4 ARTIST RECORDS SET DURING THE EVENING Jussi Pylkkänen, Christie’s Global President and auctioneer for The George Michael Collection selling Careless Whisper by Jim Lambie for £175,000 / $232,400 / €204,925. © Christie’s Images Limited 2019 / Rankin London – The much-anticipated auction of the art collection of George Michael, British singer and songwriter, and icon of the imaginative spirit of the 1980s and 1990s, has realised £9,264,000 / $12,302,590 / €10,848,145. Proceeds from the sale will be used to continue George Michael’s philanthropic work. Having attracted over 12,000 visitors to the pre-sale exhibition, 24% of registrants to The George Michael Collection were new to Christie’s. The evening auction welcomed registered bidders from 27 countries across 5 continents, reflecting the global appeal of George Michael and the YBAs. The evening sale comprised 60 lots and was 100% sold, with competitive bidding in the saleroom in London and via simulcast from New York, in addition to online via Christie’s Live™. The standalone online sale continues until lunchtime on Friday 15th March, after which point the combined total realised will be announced. Jussi Pylkkänen, Global President of Christie’s, and auctioneer for the night commented: “Tonight’s sale was another great moment for the London art market and particularly for so many YBA artists. -

N.Paradoxa Online Issue 4, Aug 1997

n.paradoxa online, issue 4 August 1997 Editor: Katy Deepwell n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 1 Published in English as an online edition by KT press, www.ktpress.co.uk, as issue 4, n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal http://www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/nparadoxaissue4.pdf August 1997, republished in this form: January 2010 ISSN: 1462-0426 All articles are copyright to the author All reproduction & distribution rights reserved to n.paradoxa and KT press. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying and recording, information storage or retrieval, without permission in writing from the editor of n.paradoxa. Views expressed in the online journal are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the editor or publishers. Editor: [email protected] International Editorial Board: Hilary Robinson, Renee Baert, Janis Jefferies, Joanna Frueh, Hagiwara Hiroko, Olabisi Silva. www.ktpress.co.uk The following article was republished in Volume 1, n.paradoxa (print version) January 1998: N.Paradoxa Interview with Gisela Breitling, Berlin artist and art historian n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 2 List of Contents Editorial 4 VNS Matrix Bitch Mutant Manifesto 6 Katy Deepwell Documenta X : A Critique 9 Janis Jefferies Autobiographical Patterns 14 Ann Newdigate From Plants to Politics : The Particular History of A Saskatchewan Tapestry 22 Katy Deepwell Reading in Detail: Ndidi Dike Nnadiekwe (Nigeria) 27 N.Paradoxa Interview with Gisela Breitling, Berlin artist and art historian 35 Diary of an Ageing Art Slut 44 n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 3 Editorial, August 1997 The more things change, the more they stay the same or Plus ca change..