The Bauhaus Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 1 December 2009 DRAFT Jonathan Petropoulos Bridges from the Reich: the Importance of Émigré Art Dealers As Reflecte

Working Paper--Draft 1 December 2009 DRAFT Jonathan Petropoulos Bridges from the Reich: The Importance of Émigré Art Dealers as Reflected in the Case Studies Of Curt Valentin and Otto Kallir-Nirenstein Please permit me to begin with some reflections on my own work on art plunderers in the Third Reich. Back in 1995, I wrote an article about Kajetan Mühlmann titled, “The Importance of the Second Rank.” 1 In this article, I argued that while earlier scholars had completed the pioneering work on the major Nazi leaders, it was now the particular task of our generation to examine the careers of the figures who implemented the regime’s criminal policies. I detailed how in the realm of art plundering, many of the Handlanger had evaded meaningful justice, and how Datenschutz and archival laws in Europe and the United States had prevented historians from reaching a true understanding of these second-rank figures: their roles in the looting bureaucracy, their precise operational strategies, and perhaps most interestingly, their complex motivations. While we have made significant progress with this project in the past decade (and the Austrians, in particular deserve great credit for the research and restitution work accomplished since the 1998 Austrian Restitution Law), there is still much that we do not know. Many American museums still keep their curatorial files closed—despite protestations from researchers (myself included)—and there are records in European archives that are still not accessible.2 In light of the recent international conference on Holocaust-era cultural property in Prague and the resulting Terezin Declaration, as well as the Obama Administration’s appointment of Stuart Eizenstat as the point person regarding these issues, I am cautiously optimistic. -

The Creative Output of Alexej Von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864

The creative output of Alexej von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864 - Wiesbaden, Germany, 1941) is dened by a simultaneously visual and spiritual quest which took the form of a recurring, almost ritual insistence on a limited number of pictorial motifs. In his memoirs the artist recalled two events which would be crucial for this subsequent evolution. The rst was the impression made on him as a child when he saw an icon of the Virgin’s face reveled to the faithful in an Orthodox church that he attended with his family. The second was his rst visit to an exhibition of paintings in Moscow in 1880: “It was the rst time in my life that I saw paintings and I was touched by grace, like the Apostle Paul at the moment of his conversion. My life was totally transformed by this. Since that day art has been my only passion, my sancta sanctorum, and I have devoted myself to it body and soul.” Following initial studies in art in Saint Petersburg, Jawlensky lived and worked in Germany for most of his life with some periods in Switzerland. His arrival in Munich in 1896 brought him closer contacts with the new, avant-garde trends while his exceptional abilities in the free use of colour allowed him to achieve a unique synthesis of Fauvism and Expressionism in a short space of time. In 1909 Jawlensky, his friend Kandinsky and others co-founded the New Association of Artists in Munich, a group that would decisively inuence the history of modern art. Jawlensky also participated in the activities of Der Blaue Reiter [the Blue Rider], one of the fundamental collectives for the formulation of the Expressionist language and abstraction. -

Frankfurt Und Der Aufbruch in Die Ungegenständlichkeit

Originalveröffentlichung in: Freigang, Christian (Hrsg.): Das "neue" Frankfurt : Innovationen in der Frankfurter Kunst vom Mittelalter bis heute ; Vorträge der 1. Frankfurter Bürger-Universität, Wiesbaden 2010, S. 74-86 Frankfurt und der Aufbruch in die Ungegenständlichkeit Thomas Kirchner auf sich, da es ihr nicht oder nicht ausreichend gelungen war, sich einem breiten Publikum Frankfurt und die Malerei der Moderne: Da verständlich zu machen, dabei aber - und dies bei denkt man vielleicht zunächst an die späten unterschied die Situation in Deutschland von 20er Jahre, in denen die Stadt durch kommuna den übrigen westlichen Ländern - eine große le Kulturpolitik und privates Mäzenatentum zu Sichtbarkeit besaß, hatten sich doch hier die einem Ort künstlerischer Innovation avancierte Museen und die privaten Sammlungen in einem und u.a. so bedeutenden Vertreter der Moderne hohen Maße der Moderne geöffnet. Dabei hatte wie Max Beckmann oder Willi Baumeister für zumindest ein Teil der Moderne anfangs durch die Kunstschule des Städel gewonnen werden aus mit den Ideen der Nationalsozialisten ge konnten. Weniger bekannt ist die zentrale Rolle liebäugelt. Emil Noldes Parteimitgliedschaft in der Mainmetropole für die Kunst nach dem 2. der NSDAP ist bekannt, auch Ernst Ludwig Weltkrieg. Um sie besser einschätzen zu können, Kirchners tiefe Enttäuschung, von den neu scheint es indes hilfreich, ein wenig auszuho en Machthabern nicht als Repräsentant einer len. Die Ausführungen nehmen ihren Ausgang neuen, dezidiert .deutschen' Kunst anerkannt von dem Versuch einer Neuorientierung der zu werden. Und ein Teil der Nationalsozialis Kunst nach dem Niedergang des Dritten Rei ten - unter ihnen der Propagandaminister Jo ches, wie man ihn mit besonderem Nachdruck seph Goebbels - war eine Zeitlang durchaus in Berlin und im Osten Deutschlands beobach gewillt, das Angebot anzunehmen und den ten kann, um sich schrittweise dem Südwesten deutschen Expressionismus als die Kunst der des Landes und Frankfurt zu nähern. -

A Guide for Holders of the International Association of Art Card Prepared with Contributions from the Slovak Union of Visual Arts (Slovenská Výtvarná Únia) 2017

A guide for holders of the International Association of Art card Prepared with contributions from the Slovak Union of Visual Arts (Slovenská výtvarná únia) 2017 The International Association of Art (IAA/AIAP) is a non-governmental organization working in official partnership with UNESCO. Its objectives are to stimulate international cooperation among visual artists of all countries, nations or peoples, to improve the socio-economic position of artists nationally and internationally, and to defend their material and moral rights. The IAA issues identity cards to professional visual artists. This card allows free or discounted admission to many galleries and museums in countries around the world. The card is a tool for the lifelong education of artists in their professional artistic research. These institutions, large or small, recognize the benefit they gain from enabling the artists, like art critics and journalists, to visit exhibitions, art events and collections of art, to carry on research, and to gain inspiration. As a member within the IAA network, CARFAC National issues IAA cards exclusively to Canadian professional artists that are members of CARFAC upon request. Only National Committees of the IAA may issue the card. Where to use the IAA card This document includes a chart detailing selected institutions that offer free or discounted admission prices, or other perks to IAA card holders while travelling abroad. This information was obtained from surveying recent users of the card and IAA National Committees worldwide, and is updated regularly – most recently in 2017 by the Slovak Union of Visual Arts (SUVA). Users will find that different areas in Europe are more receptive to the card than others. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

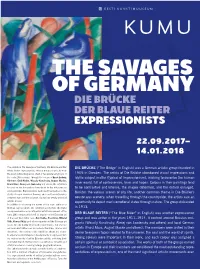

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

Claes-Göran Holmberg

fLaMMan claes-Göran holmberg Precursors swedish avant-garde groups were very late in founding their own magazines. in france and Germany, little magazines had been pub- lished continuously from the romantic era onwards. a magazine was an ideal platform for the consolidation of a new movement in its formative phase. it was a collective thrust at the heart of the enemy: the older generation, the academies, the traditionalists. By showing a united front (through programmatic declarations, manifestos, es- says etc.) you assured the public that you were to be reckoned with. almost every new artist group or current has tried to create a mag- azine to define and promote itself. the first swedish little magazine to embrace the symbolist and decadent movements of fin-de-siècle europe was Med pensel och penna (With paintbrush and pen, 1904-1905), published in Uppsala by the society of “Les quatres diables”, a group of young poets and students engaged in aestheticism and Baudelaire adulation. Mem- bers were the poet and student in slavic languages sigurd agrell (1881-1937), the student and later professor of art history harald Brising (1881-1918), the student of philosophy and later professor of psychology John Landquist (1881-1974), and the author sven Lidman (1882-1960); the poet sigfrid siwertz (1882-1970) also joined the group later. the magazine did not leave any great impact on swedish literature but it helped to spread the Jugend style of illu- stration, the contemporary love-hate relationship with the city and the celebration of the intoxicating powers of beauty and deca- dence. -

DER BLAUE REITER Textpuzzle

MDS 3.2 Unterrichtsprojekte in der Sekundarstufe Freiburg vom 29.06. bis 19.07.2014 Ozana Klein, Gabriele Weiß, Alexandra Effe DER BLAUE REITER Textpuzzle Der Blaue Reiter ist die Bezeichnung für eine Künstlergruppe Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts in München. Der Name wurde von Wassily Kandinsky und Franz Marc gewählt. Beide waren Maler und Künstler. Kandinsky hatte bereits 1909 ein Bild … … mit dem Titel „Der Blaue Reiter“ geschaffen. Was die Bezeichnung betrifft, sagte Kandinsky: „Den Namen „Der Blaue Reiter“ erfanden wir am Kaffeetisch in der Gartenlaube in Sindelsdorf. Beide liebten wir Blau: Marc – Pferde und ich – Reiter. So kam der Name … … von selbst.“ Zur Farbe Blau schrieb Kandinsky einmal: „Sie weckt in ihm die Sehnsucht nach Reinem und Übersinnlichem. Es ist die Farbe des Himmels“. August Macke und Franz Marc waren überzeugt, dass jeder Mensch eine innere und eine äußere Erlebniswelt besitzt, die durch die Kunst … … zusammengeführt werden. Außerdem glaubten sie an die Gleichberechtigung aller Kunstformen. Faktisch zählt der Blaue Reiter zum Expressionismus.Kandinsky und Marc gehörten zuerst einer anderen Künstlergruppe an. Sie hieß „Neue Künstlervereinigung München“. Aber besonders Kandinsky hatte … …immer öfter Streit mit den eher traditionell denkenden Mitgliedern der Gruppe wegen seiner sehr abstrakten Malerei und so traten er und Franz Marc 1911 aus. Sie organisierten noch im selben Jahr die erste Blaue-Reiter-Ausstellung, die … … ein großer Erfolg wurde. Die Künstlergruppe „Der Blaue Reiter“ war geboren. Von Anfang an zur Gruppe gehörten auch August Macke und Gabriele Münter, die langjährige Lebensgefährtin von Kandinsky. Sie lebten zusammen in … …Murnau, in der Nähe von Garmisch Partenkirchen im Voralpenland. Ganz in der Nähe, in Sindelsdorf, wohnten Franz und Marie Marc, zu denen sie engen Kontakt hatten. -

THE PRESENCE of SAND in WASSILY KANDINSKY's PARISIAN PAINTINGS by ASHLEY DENISE MILLWOOD DR. LUCY CURZON, COMMITTEE CHAIR

THE PRESENCE OF SAND IN WASSILY KANDINSKY’S PARISIAN PAINTINGS by ASHLEY DENISE MILLWOOD DR. LUCY CURZON, COMMITTEE CHAIR DR. MINDY NANCARROW DR. JESSICA DALLOW A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Joint Program in Art History in the Graduate Schools of The University of Alabama at Birmingham and The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2013 Copyright Ashley Denise Millwood 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Despite the extensive research that has been done on Wassily Kandinsky, little has been said about his use of sand during the decade that he spent in Paris. During this time, Kandinsky’s work shows a significant shift in both style and technique. One particular innovation was the addition of sand, and I find it interesting that this aspect of Kandinsky’s career has not been fully explored. I saw Kandinsky’s use of sand as an interesting addition to his work, and I questioned his use of this material. The lack of research in this area gave me the opportunity to formulate a theory as to why Kandinsky used sand and no other extraneous material. This examination of Kandinsky’s use of sand will contribute to the overall understanding that we have of his work by providing us with a theory and a purpose behind his use of sand. The purpose was to underscore the spirituality that can be found in his artworks. ii DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to everyone who helped me in both my research and my writing. -

Alexander Von Salzmann 1874 Tbilisi (Georgia) – 1934 Leysin (Switzerland)

Alexander von Salzmann 1874 Tbilisi (Georgia) – 1934 Leysin (Switzerland) A native of Tbilisi, Alexander von Salzmann was born into a cultivated family and received a thorough upbringing and early training in art, music and drama. Fluent in four languages – Russian, German, English and French – he was often described as sensitive and amiable but at the same time reputed to be unreliable and indolent. He trained as a painter in Moscow, later moving to Munich where he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in 1898 to study under Franz Stuck. Two years later, Wassily Kandinsky joined the same painting class. A large number of Russian artists were living and working in Munich around the turn of the twentieth century. Kandinsky, who had a strong network of contacts within Schwabing’s vibrant art world, introduced Salzmann to one of his many Russian contacts – the painter Alexej von Jawlensky. Jawlensky was romantically involved with Marianne von Werefkin, a Russian aristocrat and painter who had made the decision to interrupt her own artistic Alexander von Salzmann, Self-portrait, career to further Jawlensky’s painting. In her elegant Munich 1905 apartment Werefkin hosted a Salon which grew to be a hub of literary and artistic exchange. Salzmann soon became a regular visitor and before long was making advances to his hostess. Despite a significant age difference, they became lovers but the affair ended abruptly in 1905. Six years later Kandinsky, Jawlensky and Werefkin formed The Blue Rider, one of the leading artists’ groups of the twentieth century. Like many other Munich-based, emerging artists of the period Salzmann earned his living as an illustrator for the magazine Jugend. -

Max Beckmann Alexej Von Jawlensky Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Fernand Léger Emil Nolde Pablo Picasso Chaim Soutine

MMEAISSTTEERRWPIECREKSE V V MAX BECKMANN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER FERNAND LÉGER EMIL NOLDE PABLO PICASSO CHAIM SOUTINE GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES V MASTERPIECES V GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS MAX BECKMANN KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE 6 STILLEBEN MIT WEINGLÄSERN UND KATZE 1929 STILL LIFE WITH WINE GLASSES AND CAT 16 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY STILLEBEN MIT OBSTSCHALE 1907 STILL LIFE WITH BOWL OF FRUIT 26 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER LUNGERNDE MÄDCHEN 1911 GIRLS LOLLING ABOUT 36 MÄNNERBILDNIS LEON SCHAMES 1922 PORTRAIT OF LEON SCHAMES 48 FERNAND LÉGER LA FERMIÈRE 1953 THE FARMER 58 EMIL NOLDE BLUMENGARTEN G (BLAUE GIEßKANNE) 1915 FLOWER GARDEN G (BLUE WATERING CAN) 68 KINDER SOMMERFREUDE 1924 CHILDREN’S SUMMER JOY 76 PABLO PICASSO TROIS FEMMES À LA FONTAINE 1921 THREE WOMEN AT THE FOUNTAIN 86 CHAIM SOUTINE LANDSCHAFT IN CAGNES ca . 1923-24 LANDSCAPE IN CAGNES 98 KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE MAX BECKMANN oil on canvas Provenance 1946 Studio of the Artist 60 x 40,5 cm Hanns and Brigitte Swarzenski, New York 5 23 /8 x 16 in. Private collection, USA (by descent in the family) signed and dated lower right Private collection, Germany (since 2006) Göpel 71 2 Exhibited Busch Reisinger Museum, Cambridge/Mass. 1961. 20 th Century Germanic Art from Private Collections in Greater Boston. N. p., n. no. (title: Leaving the restaurant ) Kunsthalle, Mannheim; Hypo Kunsthalle, Munich 2 01 4 - 2 01 4. Otto Dix und Max Beckmann, Mythos Welt. No. 86, ill. p. 156. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture CUT AND PASTE ABSTRACTION: POLITICS, FORM, AND IDENTITY IN ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST COLLAGE A Dissertation in Art History by Daniel Louis Haxall © 2009 Daniel Louis Haxall Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Daniel Haxall has been reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Leo G. Mazow Curator of American Art, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Joyce Henri Robinson Curator, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Adam Rome Associate Professor of History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT In 1943, Peggy Guggenheim‘s Art of This Century gallery staged the first large-scale exhibition of collage in the United States. This show was notable for acquainting the New York School with the medium as its artists would go on to embrace collage, creating objects that ranged from small compositions of handmade paper to mural-sized works of torn and reassembled canvas. Despite the significance of this development, art historians consistently overlook collage during the era of Abstract Expressionism. This project examines four artists who based significant portions of their oeuvre on papier collé during this period (i.e. the late 1940s and early 1950s): Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell, Anne Ryan, and Esteban Vicente. Working primarily with fine art materials in an abstract manner, these artists challenged many of the characteristics that supposedly typified collage: its appropriative tactics, disjointed aesthetics, and abandonment of ―high‖ culture.