CARNOT CYCLE Do Not Trouble Students with History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, Heat, and Entropy

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, heat, and entropy Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� State functions ..............................................................................................................................................................................2� Path dependent variables: heat and work..................................................................................................................................2� DEFINING TEMPERATURE ...................................................................................................................................................................4� The zeroth law of thermodynamics .............................................................................................................................................4� The absolute temperature scale ..................................................................................................................................................5� CONSEQUENCES OF THE RELATION BETWEEN TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND ENTROPY: HEAT CAPACITY .......................................6� The difference between heat and temperature ...........................................................................................................................6� Defining heat capacity.................................................................................................................................................................6� -

HEAT and TEMPERATURE Heat Is a Type of ENERGY. When Absorbed

HEAT AND TEMPERATURE Heat is a type of ENERGY. When absorbed by a substance, heat causes inter-particle bonds to weaken and break which leads to a change of state (solid to liquid for example). Heat causing a phase change is NOT sufficient to cause an increase in temperature. Heat also causes an increase of kinetic energy (motion, friction) of the particles in a substance. This WILL cause an increase in TEMPERATURE. Temperature is NOT energy, only a measure of KINETIC ENERGY The reason why there is no change in temperature at a phase change is because the substance is using the heat only to change the way the particles interact (“stick together”). There is no increase in the particle motion and hence no rise in temperature. THERMAL ENERGY is one type of INTERNAL ENERGY possessed by an object. It is the KINETIC ENERGY component of the object’s internal energy. When thermal energy is transferred from a hot to a cold body, the term HEAT is used to describe the transferred energy. The hot body will decrease in temperature and hence in thermal energy. The cold body will increase in temperature and hence in thermal energy. Temperature Scales: The K scale is the absolute temperature scale. The lowest K temperature, 0 K, is absolute zero, the temperature at which an object possesses no thermal energy. The Celsius scale is based upon the melting point and boiling point of water at 1 atm pressure (0, 100o C) K = oC + 273.13 UNITS OF HEAT ENERGY The unit of heat energy we will use in this lesson is called the JOULE (J). -

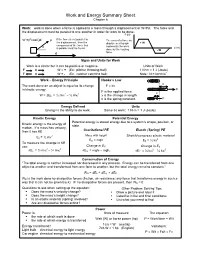

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Heat Energy a Science A–Z Physical Series Word Count: 1,324 Heat Energy

Heat Energy A Science A–Z Physical Series Word Count: 1,324 Heat Energy Written by Felicia Brown Visit www.sciencea-z.com www.sciencea-z.com KEY ELEMENTS USED IN THIS BOOK The Big Idea: One of the most important types of energy on Earth is heat energy. A great deal of heat energy comes from the Sun’s light Heat Energy hitting Earth. Other sources include geothermal energy, friction, and even living things. Heat energy is the driving force behind everything we do. This energy gives us the ability to run, dance, sing, and play. We also use heat energy to warm our homes, cook our food, power our vehicles, and create electricity. Key words: cold, conduction, conductor, convection, energy, evaporate, fire, friction, fuel, gas, geothermal heat, geyser, heat energy, hot, insulation, insulator, lightning, liquid, matter, particles, radiate, radiant energy, solid, Sun, temperature, thermometer, transfer, volcano Key comprehension skill: Cause and effect Other suitable comprehension skills: Compare and contrast; classify information; main idea and details; identify facts; elements of a genre; interpret graphs, charts, and diagram Key reading strategy: Connect to prior knowledge Other suitable reading strategies: Ask and answer questions; summarize; visualize; using a table of contents and headings; using a glossary and bold terms Photo Credits: Front cover: © iStockphoto.com/Julien Grondin; back cover, page 5: © iStockphoto.com/ Arpad Benedek; title page, page 20 (top): © iStockphoto.com/Anna Ziska; pages 3, 9, 20 (bottom): © Jupiterimages Corporation; -

TEMPERATURE, HEAT, and SPECIFIC HEAT INTRODUCTION Temperature and Heat Are Two Topics That Are Often Confused

TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND SPECIFIC HEAT INTRODUCTION Temperature and heat are two topics that are often confused. Temperature measures how hot or cold an object is. Commonly this is measured with the aid of a thermometer even though other devices such as thermocouples and pyrometers are also used. Temperature is an intensive property; it does not depend on the amount of material present. In scientific work, temperature is most commonly expressed in units of degrees Celsius. On this scale the freezing point of water is 0oC and its boiling point is 100oC. Heat is a form of energy and is a phenomenon that has its origin in the motion of particles that make up a substance. Heat is an extensive property. The unit of heat in the metric system is called the calorie (cal). One calorie is defined as the amount of heat necessary to raise 1 gram of water by 1oC. This means that if you wish to raise 7 g of water by 4oC, (4)(7) = 28 cal would be required. A somewhat larger unit than the calorie is the kilocalorie (kcal) which equals 1000 cal. The definition of the calorie was made in reference to a particular substance, namely water. It takes 1 cal to raise the temperature of 1 g of water by 1oC. Does this imply perhaps that the amount of heat energy necessary to raise 1 g of other substances by 1oC is not equal to 1 cal? Experimentally we indeed find this to be true. In the modern system of international units heat is expressed in joules and kilojoules. -

Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, Thermodynamic Inequalities

Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, Thermodynamic Inequalities Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities A.G. Petukhov, PHYS 743 October 4, 2017 Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, ThermodynamicA.G. Petukhov,October Inequalities PHYS 4, 743 2017 1 / 12 Maximum Work If a thermally isolated system is in non-equilibrium state it may do work on some external bodies while equilibrium is being established. The total work done depends on the way leading to the equilibrium. Therefore the final state will also be different. In any event, since system is thermally isolated the work done by the system: jAj = E0 − E(S); where E0 is the initial energy and E(S) is final (equilibrium) one. Le us consider the case when Vinit = Vfinal but can change during the process. @ jAj @E = − = −Tfinal < 0 @S @S V The entropy cannot decrease. Then it means that the greater is the change of the entropy the smaller is work done by the system The maximum work done by the system corresponds to the reversible process when ∆S = Sfinal − Sinitial = 0 Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, ThermodynamicA.G. Petukhov,October Inequalities PHYS 4, 743 2017 2 / 12 Clausius Theorem dS 0 R > dS < 0 R S S TA > TA T > T B B A δQA > 0 B Q 0 δ B < The system following a closed path A: System receives heat from a hot reservoir. Temperature of the thermostat is slightly larger then the system temperature B: System dumps heat to a cold reservoir. Temperature of the system is slightly larger then that of the thermostat Chapter II. -

Entropy: Is It What We Think It Is and How Should We Teach It?

Entropy: is it what we think it is and how should we teach it? David Sands Dept. Physics and Mathematics University of Hull UK Institute of Physics, December 2012 We owe our current view of entropy to Gibbs: “For the equilibrium of any isolated system it is necessary and sufficient that in all possible variations of the system that do not alter its energy, the variation of its entropy shall vanish or be negative.” Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, 1875 And Maxwell: “We must regard the entropy of a body, like its volume, pressure, and temperature, as a distinct physical property of the body depending on its actual state.” Theory of Heat, 1891 Clausius: Was interested in what he called “internal work” – work done in overcoming inter-particle forces; Sought to extend the theory of cyclic processes to cover non-cyclic changes; Actively looked for an equivalent equation to the central result for cyclic processes; dQ 0 T Clausius: In modern thermodynamics the sign is negative, because heat must be extracted from the system to restore the original state if the cycle is irreversible . The positive sign arises because of Clausius’ view of heat; not caloric but still a property of a body The transformation of heat into work was something that occurred within a body – led to the notion of “equivalence value”, Q/T Clausius: Invented the concept “disgregation”, Z, to extend the ideas to irreversible, non-cyclic processes; TdZ dI dW Inserted disgregation into the First Law; dQ dH TdZ 0 Clausius: Changed the sign of dQ;(originally dQ=dH+AdL; dL=dI+dW) dHdQ Derived; dZ 0 T dH Called; dZ the entropy of a body. -

Lecture 6: Entropy

Matthew Schwartz Statistical Mechanics, Spring 2019 Lecture 6: Entropy 1 Introduction In this lecture, we discuss many ways to think about entropy. The most important and most famous property of entropy is that it never decreases Stot > 0 (1) Here, Stot means the change in entropy of a system plus the change in entropy of the surroundings. This is the second law of thermodynamics that we met in the previous lecture. There's a great quote from Sir Arthur Eddington from 1927 summarizing the importance of the second law: If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equationsthen so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observationwell these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of ther- modynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation. Another possibly relevant quote, from the introduction to the statistical mechanics book by David Goodstein: Ludwig Boltzmann who spent much of his life studying statistical mechanics, died in 1906, by his own hand. Paul Ehrenfest, carrying on the work, died similarly in 1933. Now it is our turn to study statistical mechanics. There are many ways to dene entropy. All of them are equivalent, although it can be hard to see. In this lecture we will compare and contrast dierent denitions, building up intuition for how to think about entropy in dierent contexts. The original denition of entropy, due to Clausius, was thermodynamic. -

Symptoms of Heat- Related Illness How to Protect Your

BE PREPARED FOR EXTREME HEAT Extreme heat often results in the highest annual number of deaths among all weather-related disasters. FEMA V-1004/June 2018 In most of the U.S., extreme heat is a long period (2 to 3 days) of high heat and humidity with temperatures above 90 degrees. Greater risk Can happen anywhere Humidity increases the feeling of heat as measured by a heat index IF YOU ARE UNDER AN EXTREME HEAT WARNING Check on family members Find air conditioning, if possible. and neighbors. Avoid strenuous activities. Drink plenty of fluids. Watch for heat cramps, heat Watch for heat illness. exhaustion, and heat stroke. Wear light clothing. Never leave people or pets in a closed car. HOW TO STAY SAFE WHEN EXTREME HEAT THREATENS Prepare Be Safe Recognize NOW DURING +RESPOND Find places in your community where Never leave a child, adult, or animal Know the signs and ways to treat you can go to get cool. alone inside a vehicle on a warm day. heat-related illness. Try to keep your home cool: Find places with air conditioning. Heat Cramps Libraries, shopping malls, and • Signs: Muscle pains or spasms in • Cover windows with drapes community centers can provide a cool the stomach, arms, or legs. or shades. place to take a break from the heat. • Actions: Go to a cooler location. • Weather-strip doors and Wear a If you’re outside, find shade. Remove excess clothing. Take windows. hat wide enough to protect your face. sips of cool sports drinks with salt and sugar. Get medical help if • Use window reflectors such as Wear loose, lightweight, light- cramps last more than an hour. -

Work-Energy for a System of Particles and Its Relation to Conservation Of

Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Energy Balance In your study of engineering and physics, you will run across a number of engineering concepts related to energy. Three of the most common are Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Engineering Balance. The Conservation of Energy is treated in this course as one of the overarching and fundamental physical laws. The other two concepts are special cases and only apply under limited conditions. The purpose of this note is to review the pedigree of the Work-Energy Principle, to show how the more general Mechanical Energy Bal- ance is developed from Conservation of Energy, and finally to describe the conditions under which the Mechanical Energy Balance is preferred over the Work-Energy Principle. Work-Energy Principle for a Particle Consider a particle of mass m and velocity V moving in a gravitational field of strength g sub- G ject to a surface force Rsurface . Under these conditions, writing Conservation of Linear Momen- tum for the particle gives the following: d mV= R+ mg (1.1) dt ()Gsurface Forming the dot product of Eq. (1.1) with the velocity of the particle and rearranging terms gives the rate form of the Work-Energy Principle for a particle: 2 dV⎛⎞ d d ⎜⎟mmgzRV+=() surfacei G ⇒ () EEWK += GP mech, in (1.2) dt⎝⎠2 dt dt Gravitational mechanical Kinetic potential power into energy energy the system Recall that mechanical power is defined as WRmech, in= surfaceiV G , the dot product of the surface force with the velocity of its point of application. -

Module P7.4 Specific Heat, Latent Heat and Entropy

FLEXIBLE LEARNING APPROACH TO PHYSICS Module P7.4 Specific heat, latent heat and entropy 1 Opening items 4 PVT-surfaces and changes of phase 1.1 Module introduction 4.1 The critical point 1.2 Fast track questions 4.2 The triple point 1.3 Ready to study? 4.3 The Clausius–Clapeyron equation 2 Heating solids and liquids 5 Entropy and the second law of thermodynamics 2.1 Heat, work and internal energy 5.1 The second law of thermodynamics 2.2 Changes of temperature: specific heat 5.2 Entropy: a function of state 2.3 Changes of phase: latent heat 5.3 The principle of entropy increase 2.4 Measuring specific heats and latent heats 5.4 The irreversibility of nature 3 Heating gases 6 Closing items 3.1 Ideal gases 6.1 Module summary 3.2 Principal specific heats: monatomic ideal gases 6.2 Achievements 3.3 Principal specific heats: other gases 6.3 Exit test 3.4 Isothermal and adiabatic processes Exit module FLAP P7.4 Specific heat, latent heat and entropy COPYRIGHT © 1998 THE OPEN UNIVERSITY S570 V1.1 1 Opening items 1.1 Module introduction What happens when a substance is heated? Its temperature may rise; it may melt or evaporate; it may expand and do work1—1the net effect of the heating depends on the conditions under which the heating takes place. In this module we discuss the heating of solids, liquids and gases under a variety of conditions. We also look more generally at the problem of converting heat into useful work, and the related issue of the irreversibility of many natural processes. -

3. Energy, Heat, and Work

3. Energy, Heat, and Work 3.1. Energy 3.2. Potential and Kinetic Energy 3.3. Internal Energy 3.4. Relatively Effects 3.5. Heat 3.6. Work 3.7. Notation and Sign Convention In these Lecture Notes we examine the basis of thermodynamics – fundamental definitions and equations for energy, heat, and work. 3-1. Energy. Two of man's earliest observations was that: 1)useful work could be accomplished by exerting a force through a distance and that the product of force and distance was proportional to the expended effort, and 2)heat could be ‘felt’ in when close or in contact with a warm body. There were many explanations for this second observation including that of invisible particles traveling through space1. It was not until the early beginnings of modern science and molecular theory that scientists discovered a true physical understanding of ‘heat flow’. It was later that a few notable individuals, including James Prescott Joule, discovered through experiment that work and heat were the same phenomenon and that this phenomenon was energy: Energy is the capacity, either latent or apparent, to exert a force through a distance. The presence of energy is indicated by the macroscopic characteristics of the physical or chemical structure of matter such as its pressure, density, or temperature - properties of matter. The concept of hot versus cold arose in the distant past as a consequence of man's sense of touch or feel. Observations show that, when a hot and a cold substance are placed together, the hot substance gets colder as the cold substance gets hotter.