The Judiciary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of the Indian Supreme Court - and a Plea for Research

The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process Volume 9 Issue 2 Article 3 2007 Scholarly Discourse and the Cementing of Norms: The Case of the Indian Supreme Court - and a Plea for Research Jayanth K. Krishnan Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/appellatepracticeprocess Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Jayanth K. Krishnan, Scholarly Discourse and the Cementing of Norms: The Case of the Indian Supreme Court - and a Plea for Research, 9 J. APP. PRAC. & PROCESS 255 (2007). Available at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/appellatepracticeprocess/vol9/iss2/3 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process by an authorized administrator of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOLARLY DISCOURSE AND THE CEMENTING OF NORMS: THE CASE OF THE INDIAN SUPREME COURT -AND A PLEA FOR RESEARCH Jayanth K. Krishnan* I. INTRODUCTION For Americans, India has been a country of intense interest in recent years. Less than ten years ago India alarmed many around the world, including then-President Clinton, after it (and neighboring Pakistan) conducted a series of nuclear tests.' But even before this military display, India was on the radar of observers in the United States. Since opening its markets in 1991, India has been fertile ground for American entrepreneurs2 engaged in outsourcing and for other foreign investors as well. With the exception of a two-year period between 1975 and 1977, India has served as a light of democratic rule in the developing world since it gained independence from Britain in 1947. -

In Late Colonial India: 1942-1944

Rohit De ([email protected]) LEGS Seminar, March 2009 Draft. Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without permission. EMASCULATING THE EXECUTIVE: THE FEDERAL COURT AND CIVIL LIBERTIES IN LATE COLONIAL INDIA: 1942-1944 Rohit De1 On the 7th of September, 1944 the Chief Secretary of Bengal wrote an agitated letter to Leo Amery, the Secretary of State for India, complaining that recent decisions of the Federal Court were bringing the governance of the province to a standstill. “In war condition, such emasculation of the executive is intolerable”, he thundered2. It is the nature and the reasons for this “emasculation” that the paper hopes to uncover. This paper focuses on a series of confrontations between the colonial state and the colonial judiciary during the years 1942 to 1944 when the newly established Federal Court struck down a number of emergency wartime legislations. The courts decisions were unexpected and took both the colonial officials and the Indian public by surprise, particularly because the courts in Britain had upheld the legality of identical legislation during the same period. I hope use this episode to revisit the discussion on the rule of law in colonial India as well as literature on judicial behavior. Despite the prominence of this confrontation in the public consciousness of the 1940’s, its role has been downplayed in both historical and legal accounts. As I hope to show this is a result of a disciplinary divide in the historical engagement with law and legal institutions. Legal scholarship has defined the field of legal history as largely an account of constitutional and administrative developments paralleling political developments3. -

Dated 9Th October, 2018 Reg. Elevation

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA This file relates to the proposal for appointment of following seven Advocates, as Judges of the Kerala High Court: 1. Shri V.G.Arun, 2. Shri N. Nagaresh, 3. Shri P. Gopal, 4. Shri P.V.Kunhikrishnan, 5. Shri S. Ramesh, 6. Shri Viju Abraham, 7. Shri George Varghese. The above recommendation made by the then Chief Justice of the th Kerala High Court on 7 March, 2018, in consultation with his two senior- most colleagues, has the concurrence of the State Government of Kerala. In order to ascertain suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have consulted our colleagues conversant with the affairs of the Kerala High Court. Copies of letters of opinion of our consultee-colleagues received in this regard are placed below. For purpose of assessing merit and suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have carefully scrutinized the material placed in the file including the observations made by the Department of Justice therein. Apart from this, we invited all the above-named recommendees with a view to have an interaction with them. On the basis of interaction and having regard to all relevant factors, the Collegium is of the considered view that S/Shri (1) V.G.Arun, (2) N. Nagaresh, and (3) P.V.Kunhikrishnan, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. Nos. 1, 2 and 4 above) are suitable for being appointed as Judges of the Kerala High Court. As regards S/Shri S. Ramesh, Viju Abraham, and George Varghese, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. -

Supreme Court of India [ It Will Be Appreciated If

1 SUPREME COURT OF INDIA [ IT WILL BE APPRECIATED IF THE LEARNED ADVOCATES ON RECORD DO NOT SEEK ADJOURNMENT IN THE MATTERS LISTED BEFORE ALL THE COURTS IN THE CAUSE LIST ] DAILY CAUSE LIST FOR DATED : 22-04-2021 Court No. 5 (Hearing Through Video Conferencing) HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.M. KHANWILKAR HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE DINESH MAHESHWARI HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE KRISHNA MURARI (TIME : 11:00 AM) MISCELLANEOUS HEARING 2.1 Connected SLP(C) No. 2165/2021 IV-A MAHESH KUMAR VERMA NIRAJ SHARMA Versus UNION OF INDIA AND ORS. FOR ADMISSION and I.R. and IA No.16147/2021- EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT 2.2 Connected SLP(C) No. 2178/2021 IV-A RAVI KALE NIRAJ SHARMA Versus UNION OF INDIA AND ANR. FOR ADMISSION and I.R. and IA No.16333/2021- EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT 8 SLP(C) No. 26657/2019 XVI RASOI LIMITED AND ANR. KHAITAN & CO. Versus UNION OF INDIA AND ORS. B. KRISHNA PRASAD[R-1], [R-2], [R-3] {Mention Memo} IA No. 171231/2019 - EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT Court No. 6 (Hearing Through Video Conferencing) HON'BLE DR. JUSTICE D.Y. CHANDRACHUD HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE M.R. SHAH 2 (TIME : 11:00 AM) 13 Diary No. 14404-2020 IV-B UNION OF INDIA AND ORS. B. V. BALARAM DAS[P-1] Versus M/S FAMINA KNIT FABS RAJAN NARAIN[R-1] IA No. 91716/2020 - CONDONATION OF DELAY IN FILING IA No. 91717/2020 - EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT 13.1 Connected Diary No. -

Supreme Court of India

Supreme Court of India drishtiias.com/printpdf/supreme-court-of-india The Supreme Court of India is the highest judicial court and the final court of appeal under the Constitution of India, the highest constitutional court, with the power of judicial review. India is a federal State and has a single and unified judicial system with three tier structure, i.e. Supreme Court, High Courts and Subordinate Courts. Brief History of the Supreme Court of India The promulgation of Regulating Act of 1773 established the Supreme Court of Judicature at Calcutta as a Court of Record, with full power & authority. It was established to hear and determine all complaints for any crimes and also to entertain, hear and determine any suits or actions in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The Supreme Courts at Madras and Bombay were established by King George – III in 1800 and 1823 respectively. The India High Courts Act 1861 created High Courts for various provinces and abolished Supreme Courts at Calcutta, Madras and Bombay and also the Sadar Adalats in Presidency towns. These High Courts had the distinction of being the highest Courts for all cases till the creation of Federal Court of India under the Government of India Act 1935. The Federal Court had jurisdiction to solve disputes between provinces and federal states and hear appeal against Judgements from High Courts. After India attained independence in 1947, the Constitution of India came into being on 26 January 1950. The Supreme Court of India also came into existence and its first sitting was held on 28 January 1950. -

Securing the Independence of the Judiciary-The Indian Experience

SECURING THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE JUDICIARY-THE INDIAN EXPERIENCE M. P. Singh* We have provided in the Constitution for a judiciary which will be independent. It is difficult to suggest anything more to make the Supreme Court and the High Courts independent of the influence of the executive. There is an attempt made in the Constitutionto make even the lowerjudiciary independent of any outside or extraneous influence.' There can be no difference of opinion in the House that ourjudiciary must both be independent of the executive and must also be competent in itself And the question is how these two objects could be secured.' I. INTRODUCTION An independent judiciary is necessary for a free society and a constitutional democracy. It ensures the rule of law and realization of human rights and also the prosperity and stability of a society.3 The independence of the judiciary is normally assured through the constitution but it may also be assured through legislation, conventions, and other suitable norms and practices. Following the Constitution of the United States, almost all constitutions lay down at least the foundations, if not the entire edifices, of an * Professor of Law, University of Delhi, India. The author was a Visiting Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and Public International Law, Heidelberg, Germany. I am grateful to the University of Delhi for granting me leave and to the Max Planck Institute for giving me the research fellowship and excellent facilities to work. I am also grateful to Dieter Conrad, Jill Cottrell, K. I. Vibute, and Rahamatullah Khan for their comments. -

Notice of Motion for Presenting an Address to the President of India for the Removal of Mr

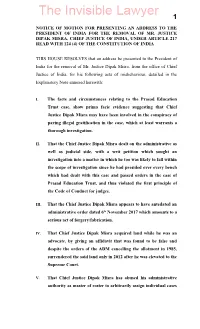

1 NOTICE OF MOTION FOR PRESENTING AN ADDRESS TO THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA FOR THE REMOVAL OF MR. JUSTICE DIPAK MISRA, CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA, UNDER ARTICLE 217 READ WITH 124 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA THIS HOUSE RESOLVES that an address be presented to the President of India for the removal of Mr. Justice Dipak Misra, from the office of Chief Justice of India, for his following acts of misbehaviour, detailed in the Explanatory Note annexed herewith: I. The facts and circumstances relating to the Prasad Education Trust case, show prima facie evidence suggesting that Chief Justice Dipak Misra may have been involved in the conspiracy of paying illegal gratification in the case, which at least warrants a thorough investigation. II. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra dealt on the administrative as well as judicial side, with a writ petition which sought an investigation into a matter in which he too was likely to fall within the scope of investigation since he had presided over every bench which had dealt with this case and passed orders in the case of Prasad Education Trust, and thus violated the first principle of the Code of Conduct for judges. III. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra appears to have antedated an administrative order dated 6th November 2017 which amounts to a serious act of forgery/fabrication. IV. That Chief Justice Dipak Misra acquired land while he was an advocate, by giving an affidavit that was found to be false and despite the orders of the ADM cancelling the allotment in 1985, surrendered the said land only in 2012 after he was elevated to the Supreme Court. -

Reportable in the Supreme Court of India Civil

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 274 OF 2014 RAM SINGH & ORS. ...PETITIONER (S) VERSUS UNION OF INDIA ...RESPONDENT (S) WITH W.P. (C) No. 261 of 2014, W.P. (C) No.278 of 2014, W.P. (C) No.297 of 2014, W.P. (C) No.298 of 2014, W.P. (C) No.305 of 2014, W.P. (C) No. 357 of 2014 & W.P. (C) No.955 of 2014 J U D G M E N T RANJAN GOGOI, J. 1. The challenge in the present group of writ petitions is to a Notification published in the Gazette of India dated 04.03.2014 by which the Jat Community has been included in the Central List of Backward Classes for the States of Bihar, 2 Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, NCT of Delhi, Bharatpur and Dholpur districts of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. The said Notification was issued pursuant to the decision taken by the Union Cabinet on 02.03.2014 to reject the advice tendered by the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC) to the contrary on the ground that the said advice “did not adequately take into account the ground realities”. RESUME OF THE CORE FACTS : 2. Pursuant to several requests received from individuals, organisations and associations for inclusion of Jats in the Central List of Backward Classes for the States of Haryana, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC) studied their claims and submitted a report on 28.11.1997. -

Justice Sabharwal's Defence Becomes Murkier

JUSTICE SABHARWAL’S DEFENCE BECOMES MURKIER: STIFLING PUBLIC EXPOSURE BY USING CONTEMPT POWERS Press Release: New Delhi 19th September 2007 Justice Sabharwal finally broke his silence in a signed piece in the Times of India. His defence proceeds by ignoring and sidestepping the inconvenient and emphasizing the irrelevant if it can evoke sympathy. To examine the adequacy of his defence, we need to see his defence against the gravamen of each charge against him. Charge No. 1. That his son’s companies had shifted their registered offices to his official residence. Justice Sabharwal’s response: That as soon as he came to know he ordered his son’s to shift it back. Our Rejoinder: This is False. In April 2007, in a recorded interview with the Midday reporter M.K. Tayal he feigned total ignorance of the shifting of the offices to his official residence. In fact, the registered offices were shifted back from his official residence to his Punjabi Bagh residence exactly on the day that the BPTP mall developers became his sons partners, making it very risky to continue at his official residence. Copies of the document showing the date of induction of Kabul Chawla, the promoter and owner of BPTP in Pawan Impex Pvt. Ltd., one of the companies of Jutstice Sabharwal’s sons, and Form no. 18 showing the shifting of the registered office from the official residence of Justice Sabharwal to his family residence on 23rd October 2004. Charge No. 2: That he called for and dealt with the sealing of commercial property case in March 2005, though it was not assigned to him. -

Constitutional Ideals and Justice in Plural Societies

L10-2016 Justice MN Venkatachaliah Born on 25th October 1929, he entered the general practice of the law in MN Venkatachaliah the year 1951 at Bangalore after obtaining University degrees in Science and law. Justice Venkatachaliah was appointed Judge of the high court of Karnataka in the year 1975 and later as Judge of the Supreme Court of India in the year 1987. He was appointed Chief Justice of India in February 1993 and held that office till his retirement in October 1994. Justice Venkatachaliah was appointed Chairman, National Human Rights Commission in 1996 and held that office till October 1999. He was nominated Chairman of the National commission to Review the Working of the Constitution in March 2000 and the National Commission gave its CONSTITUTIONAL IDEALS AND Report to the Government of India in March 2002. He was conferred “Padma Vibhushan” on 26th January 2004 by the Government of India. JUSTICE IN PLURAL SOCIETIES Justice Venkatachaliah has been associated with a number of social, cultural and service organizations. He is the Founder President of the Sarvodya International Trust. He is the Founder Patron of the “Society for Religious Harmony and Universal Peace “ New Delhi. He was Tagore Law NIAS FOUNDATION DAY LECTURE 2016 Professor of the Calcutta University. He was the chairman of the committee of the Indian Council for Medical Research to draw-up “Ethical Guidelines for Bio-Genetic research Involving Human Subjects”. Justice Venkatachaliah is the President of the Public Affairs Centre and President of the Indian Institute of World Culture. He was formerly Chancellor of the Central University of Hyderabad. -

The Hon'ble Mr Justice Y K Sabharwal

n 052 im 002 Delhi’s Moot Court Hall named after alumnus Chief Justice of India 14.01.2016 The Hon’ble Mr Justice Y K Sabharwal Mr Justice Y K Sabharwal BA Hons 1961 Hindu LLB 1964 36th Chief Justice of India 1999 – 2000 Former Judge High Court of Delhi Chief Justice High Court of Bombay Passed away 03.07.2015 Jaitley inaugurates Y K Sabharwal Moot Court hall at National Law University Delhi NEW DELHI: Union finance minister Arun Jaitley on Thursday recalled late former Chief Justice of India YK Sabharwal as one of the rare judges who was not only fair but also fearless. He had the “ability to strike” when it was required, the Minister said. Speaking at the inauguration of a moot court hall in Delhi’s National Law University (NLU) — dedicated to the former CJI , Jaitley said Justice Sabharwal was a tough judge but never sat on the bench with fixated views. “He had no likes or dislikes and had no friends in court. But his personality outside was totally different,” Jaitley reminisced, recalling his association with the former CJI who made tremendous contribution to the field of Law through his judgements. Some of the important verdicts delivered by him included declaring President’s Rule in Bihar unconstitutional and opening to judicial review the laws placed in the Ninth Schedule. A Moot Court Hall in his name in a premier law school was a fit dedication to the former CJI, Jaitley said. The Minister added : “A specialised Moot Court hall is a rare speciality and for a law school to have one is commendable.” Justice Dalveer Bhandari, Judge of International Court of Justice, spoke of how moot courts had become an integral part of legal education. -

Commendation by Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah

M. N. VENKATACHALIAH A COMMENDATION OF IIAM COMMUNITY MEDIATION SERVICE VISUALIZED BY THE INDIAN INSTITUTE OF ARBITRATION & MEDIATION. The Indian Institute of Arbitration & Mediation (IIAM), a registered society, has innovated an extremely effective idea of a decentralized, socially oriented and inexpensive Dispute Resolution Mechanism to serve the needs of the common people obviating their recourse to more expensive, embittering and protracted litigations in the courts of law. The formal dispute resolution mechanisms are wholly inappropriate to the aspirations and needs of the common people for speedy justice. I had the privilege of being on the Advisory Board of IIAM along with Mr. Justice J.S. Verma, Former Chief Justice of India, Mr. Justice K.S. Paripoornan, Former Judge, Supreme Court of India, Mr. Prabhat Kumar, Former Cabinet Secretary & Former Governor of Jharkhand, Dr. Madhav Mehra, President of World Council for Corporate Governance, UK, Dr. Abid Hussain, Former Ambassador to the US, Mr. Sudarshan Agarwal, Former Governor of Sikkim, Dr. G. Mohan Gopal, Director of the National Judicial Academy and Mr. Michael McIlwrath, Chairman, International Mediation Institute, The Hague. The Hon’ble Chief Justice of India inaugurated the “IIAM Community Mediation Service” on the 17th of January 2009 at New Delhi. Every participant extolled the great potential of this innovative scheme to bring justice to the doors of the common man under a scheme which provides for voluntary participation with the assistance of experienced lawyers, retired judges, former civil servants and other public spirited people who will act as mediators to bring about a just and mutually acceptable solution to potentially litigative situations.