Download and Identify These Features

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Host on 'Worst Year'

7 Ts&Cs apply Iceland give huge discount Claire King health: Craig Revel Horwood Kate Middleton pregnant Jenny Ryan: ‘The cat is out to emergency service Emmerdale star's health: ‘It was getting with twins on royal tour in the bag’ The Chase quizzer workers - find… diagnosis ‘I was worse’ Strictly… Pakistan?… announces… Jeremy Clarkson: ‘Wanted to top myself’ Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on 'worst year' JEREMY CLARKSON - who fronts ITV show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? - shared his thoughts on a recent study which claimed 1978 was the “worst year” in British history. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire: Jeremy criticises the contestant Earlier this week, researchers from Warwick University claimed people of Britain were at their most unhappy in 1978. The latter year and the first two months of 1979 are best remembered for the Winter of Discontent, where strikes took place and caused various disruptions. ADVERTISING 1/6 Jeremy Clarkson (/search?s=jeremy+clarkson) shared his thoughts on the study as he recalled his first year of working during the strikes. PROMOTED STORY 4x4 Magazine: the SsangYong Musso is a quantum leap forward (SsangYong UK)(https://www.ssangyonggb.co.uk/press/first-drive-ssangyong-musso/56483&utm-source=outbrain&utm- medium=musso&utm-campaign=native&utm-content=4x4-magazine?obOrigUrl=true) In his column with The Sun newspaper, he wrote: “It’s been claimed that 1978 was the worst year in British history. RELATED ARTICLES Jeremy Clarkson sports slimmer waistline with girlfriend Lisa Jeremy Clarkson: Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on his Hogan weight loss (/celebrity-news/1191860/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-girlfriend- (/celebrity-news/1192773/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-health- Lisa-Hogan-pictures-The-Grand-Tour-latest-news) Who-Wants-To-Be-A-Millionaire-age-ITV-Twitter-news) “I was going to argue with this. -

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

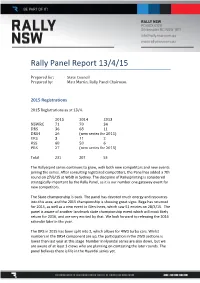

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

INTRODUCING the TOP GEAR LIMITED EDITION BUGG BBQ from BEEFEATER Searing Performance for the Meat Obsessed Motorist

PRESS RELEASE INTRODUCING THE TOP GEAR LIMITED EDITION BUGG BBQ FROM BEEFEATER Searing Performance for the Meat Obsessed Motorist “It’s Flipping Brilliant” Sydney, Australia, 19 November 2012 BeefEater, the Australian leaders in barbecue technology, has partnered with BBC Worldwide Australasia to create an innovative and compact Top Gear Limited Edition BUGG® (BeefEater Universal Gas Grill) BBQ, that will make you the envy of your mates. The Limited Edition BBQ from BeefEater comes with an exclusive Top Gear accessory bundle which includes a Stig oven mitt and apron to help you look the part while cooking. It also features a bespoke Top Gear gauge and tyre‐track temperature control knob to keep you on track whilst perfecting your meat. ‘Top Gear’s Guide on How Not to BBQ’ is also included, with helpful tips such as ‘do not attempt to modify your barbecue by fitting an aftermarket exhaust’ and ‘this barbecue is not suitable for children, or adults who behave like children’ guiding users through those trickier BBQ moments. The BBQ launches in Australia just in time for Christmas at Harvey Norman and other leading independent retailers, and will be available in the UK and Europe when the weather’s a little better. “A cool white hood, precision controls, bespoke gauges and a high performance ignition – what a way to convince the meat obsessed motorist to get out of the garage and cook dinner! This new Top Gear Limited Edition BUGG BBQ from BeefEater is a high performance vehicle, making cooking ability an optional extra,” says Elie Mansour, BBC Worldwide Australasia’s Manager Licensed Consumer Products. -

Investigation Into the the Accident of Richard Hammond

Investigation into the accident of Richard Hammond Accident involving RICHARD HAMMOND (RH) On 20 SEPTEMBER 2006 At Elvington Airfield, Halifax Way, Elvington YO41 4AU SUMMARY 1. The BBC Top Gear programme production team had arranged for Richard Hammond (RH) to drive Primetime Land Speed Engineering’s Vampire jet car at Elvington Airfield, near York, on Wednesday 20th September 2006. Vampire, driven by Colin Fallows (CF), was the current holder of the Outright British Land Speed record at 300.3 mph. 2. Runs were to be carried out in only one direction along a pre-set course on the Elvington runway. Vampire’s speed was to be recorded using GPS satellite telemetry. The intention was to record the maximum speed, not to measure an average speed over a measured course, and for RH to describe how it felt. 3. During the Wednesday morning RH was instructed how to drive Vampire by Primetime’s principals, Mark Newby (MN) and CF. Starting at about 1 p.m., he completed a series of 6 runs with increasing jet power and at increasing speed. The jet afterburner was used on runs 4 to 6, but runs 4 and 5 were intentionally aborted early. 4. The 6th run took place at just before 5 p.m. and a maximum speed of 314 mph was achieved. This speed was not disclosed to RH. 5. Although the shoot was scheduled to end at 5 p.m., it was decided to apply for an extension to 5:30 p.m. to allow for one final run to secure more TV footage of Vampire running with the after burner lit. -

A Celebration of the Fourth Best Country in the World PDF Book This Article Needs Additional Citations for Verification

THE TOP GEAR GUIDE TO BRITAIN: A CELEBRATION OF THE FOURTH BEST COUNTRY IN THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Porter | 160 pages | 01 May 2014 | Ebury Publishing | 9781849906906 | English | London, United Kingdom The Top Gear Guide to Britain: A Celebration of the Fourth Best Country in the World PDF Book This article needs additional citations for verification. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Archived from the original on 6 July Categories : British television seasons British television seasons Top Gear seasons. Doctor Who — This article is about the television series. Image zoom. Top Gear is then invited to film a car chase for the upcoming remake of The Sweeney starring Ray Winstone and Plan B, before taking on a trio of disabled war veterans on some DIY mobility scooters. After weeks of speculation about the identity of our tame racing driver, the Stig finally summons the courage to remove his helmet in front of a studio audience. In the opening episode of Series 14, the presenters were filmed taking a road trip in three grand tourers they had chosen across the country of Romania. Further complaints were also made in regards to a scene in which Clarkson donned a pork pie hat and called it a "gypsy" hat, while commenting: "I'm wearing this hat so the gypsies think I am [another gypsy]. They also pick out car-themed pieces that they like while also making their own BMW "art car". The Kurdish and Iraqi flag sway in the wind as a bonfire burns during the Noruz spring festival celebrations in the northern city of Kirkuk, about miles north of Baghdad. -

Twitter User Claims to Name UK Stars Who Gag Press 9 May 2011

Twitter user claims to name UK stars who gag press 9 May 2011 publication of 'intimate' photos of me and Jeremy Clarkson. NOT TRUE!," tweeted Khan, the ex-wife of Pakistani cricket legend turned politician Imran Khan. The release of names on Twitter came amid mounting opposition to the use of the injunctions in Britain. Top BBC broadcaster Andrew Marr admitted at the end of last month that he took out a gagging order to suppress reports of an extra-marital affair but Jemima Khan, pictured in London in February, denies said he was now "embarrassed" about the order having a super injunction preventing publication of granted in 2008. 'intimate' photos of her with British TV presenter Jeremy Clarkson. A Twitter account had more than 35,000 The journalist said his decision to go public was followers by Monday after claiming to have revealed the motivated by fears that the orders were "running names of British celebrities who have taken out gagging out of control." orders to prevent reporting about their private lives. Prime Minister David Cameron said last month that he felt "uneasy" about some of the injunctions. A Twitter account had more than 35,000 followers Cameron said judges were using human rights by Monday after claiming to have revealed the legislation "to deliver a sort of privacy law" and names of British celebrities who have taken out added that it should be up to parliament to decide gagging orders to prevent reporting about their on the balance between press freedom and private lives. privacy. The messages on the microblogging site, which (c) 2011 AFP can be read by anyone online, were an attempt to get around the so-called super-injunctions supposedly taken out against the media. -

Subaru Wrx Sti Type Ra Nbr Special Sets Sub-Seven Minute Nurburgring Lap

Subaru Of America, Inc. Media Information One Subaru Drive Camden, NJ 08103 Main Number: 856-488-8500 CONTACT: Dominick Infante Jessica Tullman (856) 488-8615 (310) 352-4400 [email protected] [email protected] SUBARU WRX STI TYPE RA NBR SPECIAL SETS SUB-SEVEN MINUTE NURBURGRING LAP Lap time of 6:57.5 is fastest ever for a sedan Nurburg, Germany , Jul 21, 2017 - Subaru of America, Inc. announced today that the Subaru WRX STI Type RA NBR Special set a new lap record for a four-door sedan at the famous 12.8-mile Nürburgring Nordschleife race track, achieving a time of 6:57.5. A video will be released shortly. The time was achieved using the Nurburgring timing equipment and was officially verified by track officials. The WRX STI Type RA NBR Special was designed to show the capabilities of the Subaru sedan and all-wheel drive. This time attack car has set lap records at the Isle of Man TT, the Goodwood Festival of Speed hill climb (where it was also 3rd fastest overall) and now it has conquered the 12.8-mile (20.6-kilometer) lap around the Nurburgring Nordschleife in less than seven minutes. Achieving a time of six minutes and 57.5 seconds, the Prodrive-built time attack car is equipped with a rally spec 2.0-liter Boxer engine and Subaru Symmetrical All-Wheel Drive. Subaru Product Communications manager Dominick Infante commented: "We brought the WRX STI Type RA NBR Special here to set a record and call attention to the WRX STI Type RA that we will launch later this year. -

CARS and PEOPLE Škodaauto 2007 ANNUAL REPORT INVENTIVE SPIRIT

SIMPLY CLEVER CARS AND PEOPLE ŠkodaAuto 2007 ANNUAL REPORT INVENTIVE SPIRIT Jens Manske (Head of Design), Lada Dlabolová (interior designer) – posing in front of an interior model at the Škoda Auto Design Centre Jana Bonková, Věra Vasická – matching colour and upholstery samples in the background Long before a new model is designed, the technical development department begins to work on the first conceptual sketches. Upon compiling draft designs, the overall vehicle concept is ready for further elaboration. We have a lot of new ideas for products that we are developing with enthusiasm and great ambition. We are a motivated and efficient team ambitiously working on each new project whole-heartedly and with great determination. Jens Manske, Head of Design ŠKODA SUPERB CHANGE YOUR SENSE OF SPACE ŠKODA OCTAVIA RS EVERYDAY LIFE. TURBOCHARGED ŠKODA ROOMSTER FIND YOUR OWN ROOM ŠKODA FABIA LOVE AT FIRST DRIVE Škoda stands for top quality, smart solutions, roominess, attractive designs and characteristic style. Of course, the same applies for its flag-ship, the Superb. This makes the Superb the ideal limousine for people who know what they want, who are conscious about what they expect from products and brands, and who are, in this sense, very demanding. NO COMPROMISE IN SPACE AND COMFORT With its imposing interior space offer, its outstanding room in the rear passenger compartment, its smart and useful details and overall elegance, the Škoda Superb offers a consequential “big plus” in comfort, space and smart solutions. The car therefore brings a rewarding driving experience not only for the driver but also for the passengers. -

Quinton Motor Club Ltd

Quinton Motor Club Ltd Forewo rd This publication is the result of over two years of investigative research and subsequent communication with many past members of Quinton Motor Club. No formal record of the Club ’s history or its activities existed before this task was under taken. I would particularly like to acknowledge the involvement of the following: Mike & Hilary Stratton , who were the driving force behind the w hole project and have spent countless hours in research and communication with past members , far and wide, a s well as many long journeys from their home in Devon to meet with the rest of us in the Midlands. The other members of the organising committee for the fiftieth anniversary celebrations for their hospitality at meetings, contribution of ideas, research fo r memorabilia , general good humour and enthusiasm that this milestone should be fittingly celebrated (in alphabetical order): Ray Barlow, Susan Butcher, Mike Harris, Nick Jones & Graham Towns hend. This publication has only been made possible by people tur ning out cupboards, garages and lofts to unearth long forgotten gems regarding the Club and its history. Foremost in this is Mike Adams, who has been the major source of information in that he has not thrown ANYTHING away sinc e he joined the Club in the mi d -1970s. Three big cardboard boxes arrived at my house one day in the early Spring of 2008, Ginny was not hap py when they were returned just over a year later, she thought she had seen the last of them..!! Others, not on the organising committee, that h ave unearthed memorabilia are (in alphabetical order): Peter Bayliss, John Davi s, Steve Eagle, Peter Gray , Neil Henderson and finally Dave Bullock who attended the first meeting of the Club and whose recollections of the early years has enabled me to piece together the scant infor mation that still exists from fifty years ago..!! We all hope you enjoy this publication and that its contents makes you smile and brings back happy memories of your time in Quinton Motor Club . -

Top Gear Challenge

Top Gear Challenge What’s the fastest way to get across London? On Top Gear, a very popular BBC TV series about cars and driving, they decided to organize a race across London, to find the quickest way to cross a busy city. The idea was to start from Kew Bridge, in the south- west of London, and to finish the race at the check-in desk at London City Airport, in the east, a journey of approximately 15 miles. Four possible forms of transport were chosen, a bike, a car, a motorboat, and public transport. The show’s presenter, Jeremy Clarkson, took the boat and his colleague James May went by car (a large Mercedes). Richard Hammond went by bike, and The Stig took public transport. He had an Oyster card. His journey involved getting a bus, then the Tube, and then the Docklands Light Railway, an overground train which connects east and west London. They set off on a Monday morning in the rush hour… English File third edition Intermediate Student’s Book Unit 3A, p.25 © OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2013 1 Jeremy in the motorboat His journey was along the River Thames. For the first few miles there was a speed limit of nine miles an hour, because there are so many ducks and other birds in that part of the river. The river was confusing, and at one point he realized that he was going in the wrong direction. But he turned round and got back onto the right route. Soon he was going past Fulham football ground. -

Top Gear's Target Audience

Josh Siegel / Mia’s Section / 11/4/2010 Top Gear’s Target Audience (Revision) I have had a long-standing love of the BBC car show Top Gear, to the point where I can identify the episode number from a particular quote. Many of my friends feel similarly. The difference is that my friends don’t like cars, while I live and breathe gasoline fumes. The love of Top Gear is universal; I’ve met people on airplanes, at bars, and walking down the street who immediately recognize the name and are able to remember specific scenes, quote the hosts, or otherwise demonstrate an intimate knowledge of the program. So why is the show so well loved? How has the BBC managed to get so many people so interested in my favorite hobby? Other documentaries and automotive programs hardly get any recognition – you never hear anyone talking about Modern Marvels or Ultimate Car Build-Off. I believe that the reason for Top Gear’s mass appeal is that the BBC has done away with many of the genre’s historic formalities and instead focused on delivering entertainment as effectively as possible. This paper analyzes the documentary (defined as such by the hosts themselves in Series 12 Episode 2) in an effort to determine how the show has broken with genre conventions in order to make car culture more accessible to the average person without alienating die-hard car aficionados. The love of Top Gear is universal. One columnist states, “occasionally offensive and entirely environmentally unfriendly, who watches this stuff? Okay I admit it: me.