The Freycinet Map of 1811 – Is It the First Complete Map of Australia?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

Vertical Motions of Australia During the Cretaceous

Basin Research (1994) 6,63-76 The planform of epeirogeny: vertical motions of Australia during the Cretaceous Mark Russell and Michael Gurnis* Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1063,USA ABSTRACT Estimates of dynamic motion of Australia since the end of the Jurassic have been made by modelling marine flooding and comparing it with palaeogeographical reconstructions of marine inundation. First, sediment isopachs were backstripped from present-day topography. Dynamic motion was determined by the displacement needed to approximate observed flooding when allowance is made for changes in eustatic sea-level. The reconstructed inundation patterns suggest that during the Cretaceous, Australia remained a relatively stable platform, and flooding in the eastern interior during the Early Cretaceous was primarily the result of the regional tectonic motion. Vertical motion during the Cretaceous was much smaller than the movement since the end of the Cretaceous. Subsidence and marine flooding in the Eromanga and Surat Basins, and the subsequent 500 m of uplift of the eastern portion of the basin, may have been driven by changes in plate dynamics during the Mesozoic. Convergence along the north-east edge of Australia between 200 and 100 Ma coincides with platform sedimentation and subsidence within the Eromanga and Surat Basins. A major shift in the position of subduction at 140Ma was coeval with the marine incursion into the Eromanga. When subduction ended at 95 Ma, marine inundation of the Eromanga also ended. Subsidence and uplift of the eastern interior is consistent with dynamic models of subduction in which subsidence is generated when the dip angle of the slab decreases and uplift is generated when subduction terminates (i.e. -

Acf Final Cs

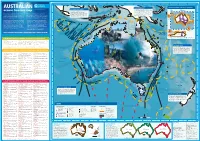

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P NORTH MARINE REGION AUSTRALIA’S OCEANS: FROM ASIA TO ANTARCTICA AUSTRALIAN www.acfonline.org.au/oceans 1 1 NORTH-WEST MARINE REGION The 700,000 square kilometres of this region cover the shallow waters of the Gulf of Carpentaria and the oceans treasure map The region’s one million square kilometres contain Arafura and Timor seas. Inshore ocean life is an extensive continental shelf, diverse and influenced by the mixing of freshwater runoff from productive coral reefs and some of the best examples Australia’s oceans are the third largest and most Without our oceans, Australia’s environment, tropical rainfall and wind and storm-driven surges of tropical and arid-zone mangroves in the world. of sea water. Many turtles, dugongs, dolphins and diverse on Earth. Three major oceans, five climate economy, society and culture would be very The breeding and feeding grounds for a number of seabirds travel through the area. threatened migratory species are found here along Christmas zones, varied underwater seascapes and mighty different. They are our lifestyle-support system. But Island currents bring together an amazing wealth of ocean they have suffered from our use and less than five 2 with large turtle and seabird populations. 2 Cocos treasures. This map shows you where to find them. per cent is free of fishing and offshore oil and gas. e Ara in fura C R Keeling r any eg a ons io Islands M n Tor Norfolk res rth Island Australia has the world’s largest area of coral reefs, To protect our ocean treasures Australia needs to: o Strait TIMOR N DARWIN Van Diemen Raine Island the largest single reef−the Great Barrier Reef−and • create a network of marine national parks free of SEA Rise Wessel the largest seagrass meadow in Shark Bay. -

Captain Louis De Freycinet

*Catalogue title pages:Layout 1 13/08/10 2:51 PM Page 1 CAPTAIN LOUIS DE FREYCINET AND HIS VOYAGES TO THE TERRES AUSTRALES *Catalogue title pages:Layout 1 13/08/10 2:51 PM Page 3 HORDERN HOUSE rare books • manuscripts • paintings • prints 77 VICTORIA STREET POTTS POINT NSW 2011 AUSTRALIA TEL (61-2) 9356 4411 FAX (61-2) 9357 3635 [email protected] www.hordern.com CONTENTS Introduction I. The voyage of the Géographe and the Naturaliste under Nicolas Baudin (1800-1804) Brief history of the voyage a. Baudin and Flinders: the official narratives 1-3 b. The voyage, its people and its narrative 4-29 c. Freycinet’s Australian cartography 30-37 d. Images, chiefly by Nicolas Petit 38-50 II. The voyage of the Uranie under Louis de Freycinet (1817-1820) Brief history of the voyage a. Freycinet and King: the official narratives 51-54 b. Preparations and the voyage 55-70 c. Freycinet constructs the narrative 71-78 d. Images of the voyage and the artist Arago’s narrative 79-92 Appendix 1: The main characters Appendix 2: The ships Appendix 3: Publishing details of the Baudin account Appendix 4: Publishing details of the Freycinet account References Index Illustrated above: detail of Freycinet’s sketch for the Baudin atlas (catalogue no. 31) Illustrated overleaf: map of Australia from the Baudin voyage (catalogue no. 1) INTRODUCTION e offer for sale here an important on the contents page). To illuminate with knowledge collection of printed and original was the avowed aim of each of the two expeditions: Wmanuscript and pictorial material knowledge in the widest sense, encompassing relating to two great French expeditions to Australia, geographical, scientific, technical, anthropological, the 1800 voyage under Captain Nicolas Baudin and zoological, social, historical, and philosophical the 1817 voyage of Captain Louis-Claude de Saulces discoveries. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Susan Hunt and Paul Carter, Terre Napoleon: Australia Through French Eyes 1800-1804, published by the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, distributed by Bloomings Books (37 Burwood Road, Hawthorn, Victoria, 3122), $85 Hardback ISBN 0949753815, $45 Paperback ISBN 949753874. In Explorations, No. 8 (December 1989), I reviewed Jacqueline Bonnemain's, Elliott Forsyth's and Bernard Smith's wonderful book Baudin in Australian Waters: The Artwork of the French Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands 1800-1804, (Oxford, 1988). Although I had nothing but praise for this book, I was then pessimistic enough to declare that 'Baudin's ... name seems destined to be known by only a handful of Australians for many years to come'. Thanks to the splendid 'Terre Napoleon' exhibition, held recently in Sydney and Canberra, I have been proven delightfully wrong! The beautiful catalogue of the exhibition owes a great deal to the work of Bonnemain, Forsyth and Smith, particularly with regard to biographical and descriptive notes. Although Terre Napoleon: Australia Through French Eyes 1800-1804 is not as rich a scholarly resource as Baudin in Australian Waters ..., it is a fine example of book production and the illustrations are produced to the same high standards. It is certainly more affordable.* When Nicolas-Thomas Baudin's expedition was outfitted in Le Havre, Charles- Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846) was attracted to the prospect of adventure in southern waters and enlisted as an assistant gunner, 4th class. But when the expedition's artists deserted at He de France (Mauritius), Lesueur took on the task of official artist. -

The Meeting of Matthew Flinders and Nicolas Baudin

A Cordial Encounter? 53 A Cordial Encounter? The Meeting of Matthew Flinders and Nicolas Baudin (8-9 April, 1802) Jean Fornasiero and John West-Sooby1 The famous encounter between Nicolas Baudin and Matthew Flinders in the waters off Australia’s previously uncharted south coast has now entered the nation’s folklore. At a time when their respective countries were locked in conflict at home and competing for strategic advantage on the world stage, the two captains were able to set aside national rivalries and personal disappointments in order to greet one another with courtesy and mutual respect. Their meeting is thus portrayed as symbolic of the triumph of international co-operation over the troubled geopolitics of the day. What united the two expeditions—the quest for knowledge in the spirit of the Enlightenment—proved to be stronger than what divided them. This enduring—and endearing—image of the encounter between Baudin and Flinders is certainly well supported by the facts as we know them. The two captains did indeed conduct themselves on that occasion in an exemplary manner, readily exchanging information about their respective discoveries and advising one another about the navigational hazards they should avoid or about safe anchorages where water and other supplies could be obtained. Furthermore, the civility of their meeting points to a strong degree of mutual respect, and perhaps also to a recognition of their shared experience as navigators whom fate had thrown together on the lonely and treacherous shores of the “unknown coast” of Australia. And yet, as appealing as it may be, this increasingly idealized image of the encounter runs the risk of masking some of its subtleties and complexities. -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

Report on the Inspection of the De Freycinet Land Camp, Shark Bay, 2005

Report on the Inspection of the de Freycinet Land Camp, Shark Bay, 2005 Maritime Heritage Site Inspection Report Matthew Gainsford and Richenda Prall Assisted by Sam Bolton and Simeon Prall Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Maritime Museum Report—Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Maritime Museum, No. 196. 2005 Report on the Inspection of the de Freycinet Land Camp, Shark Bay, 2005 Contents Contents ...............................................................................................................................i List of Figures.......................................................................................................................ii Abstract ..............................................................................................................................iii Acknowledgements..............................................................................................................iii Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Background......................................................................................................................... 1 Technical data..................................................................................................................... 3 Chart excerpts..................................................................................................................... 4 Description of site ............................................................................................................... -

WABN #155 2015 Sep.Pdf

Western Australian Bird Notes Quarterly Newsletter of the Western Australian Branch of BirdLife Australia No. 155 September 2015 birds are in our nature Hooded Plover, Mylies Beach, west of Hopetoun, Fitzgerald River National Park (see p18). Photo by John Tucker Brown Quail, Bold Park (see p11). Photo by Paul Sellers See Faure Island report, p4. Figure 2 shows a fluctuation over the six surveys in the abundance of significant species in this suite of birds. Compared with 2013, in 2014 there were more Lesser Sand Plovers (682 in 2014, 676 in 2013) and Grey-tailed Tattlers (251, 237) Front cover: South Polar Skua seen off Albany (see report, p11). Photo by Plaxy Barrett Page 2 Western Australian Bird Notes, No. 155 September 2015 Western Australian Branch of EXECUTIVE Committee BirdLife Australia Office: Peregrine House Chair: Mike Bamford 167 Perry Lakes Drive, Floreat WA 6014 Co Vice Chairs: Sue Mather and Nic Dunlop Hours: Monday-Friday 9:30 am to 12.30 pm Telephone: (08) 9383 7749 Secretary: Kathryn Napier E-mail: [email protected] Treasurer: Frank O’Connor BirdLife WA web page: www.birdlife.org.au/wa Chair: Mike Bamford Committee: Mark Henryon, Paul Netscher, Sandra Wallace and Graham Wooller (three vacancies). BirdLife Western Australia is the WA Branch of the national organisation, BirdLife Australia. We are dedicated to creating a brighter future for Australian birds. General meetings: Held at the Bold Park Eco Centre, Perry Lakes Drive, Floreat, commencing 7:30 pm on the 4th Monday of the month (except December) – see ‘Coming events’ for details. Executive meetings: Held at Peregrine House on the 2nd Monday of the month. -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

Review of the Fossil Record of the Australian Land Snail Genus

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 038–050 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(1).2019.038-050 Review of the fossil record of the Australian land snail genus Bothriembryon Pilsbry, 1894 (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Bothriembryontidae): new distributional and geological data Corey S. Whisson1,2* and Helen E. Ryan3 1 Department of Aquatic Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. 2 School of Veterinary and Life Sciences, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150, Australia. 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The land snail genus Bothriembryon Pilsbry, 1894, endemic to southern Australia, contains seven fossil and 39 extant species, and forms part of the Gondwanan family Bothriembryontidae. Little published data on the geographical distribution of fossil Bothriembryon exists. In this study, fossil and modern data of Bothriembryon from nine Australian museums and institutes were mapped for the first time. The fossilBothriembryon collection in the Western Australian Museum was curated to current taxonomy. Using this data set, the geological age of fossil and extant species was documented. Twenty two extant Bothriembryon species were identified in the fossil collection, with 15 of these species having a published fossil record for the first time. Several fossil and extant species had range extensions. The geological age span of Bothriembryon was determined as a minimum of Late Oligocene to recent, with extant endemic Western Australian Bothriembryon species determined as younger, traced to Pleistocene age. Extant Bothriembryon species from the Nullarbor region were older, dated Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene. -

Planning for Sustainable Tourism on Tasmania's

planning for sustainable tourism on tasmania’s east coast component 2 - preliminary biodiversity and heritage evaluation prepared by context and coliban ecology february 2015 Disclaimer The authors do not warrant that the information in this document is free from errors or omissions. The authors do not accept any form of liability, be it contractual, tortuous, or otherwise, for the contents of this document or for any consequences arising from its use or any reliance placed upon it. The information, opinions and advice contained in this document may not relate, or be relevant, to a reader’s particular circumstances. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Version Title Date Issuer Changes A Planning for Sustainable Tourism 09.10.2014 David Barnes N/A on Tasmania’s East Coast-Draft B Planning for Sustainable Tourism 10.02.2015 David Barnes Incorporates additional comments from on Tasmania’s East Coast the Australian Government Department of Environment. 2 component 2: biodiversity and cultural heritage assessment contents Introduction