Violin Performance Training at Collegiate Schools of Music and Its Relevance to the Performance Professions: a Critique and Recommendation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choose Yourfavorite Three Concerts

CHOOSE YOUR FAVORITE THREE CONCERTS. You’ll Save 33% – That’s Up to $200 in Savings with Added Benefits Call 212-875-5656 or visit nyphil.org/CYO33 and use promo code CYO33. ** U.S. Premiere–New York Philharmonic Co-Commission with the London Philharmonic Orchestra *** World Premiere–New York Philharmonic Commission † Commissions made possible by The Marie-Josée Kravis Prize for New Music †New York City Premiere–New York Philharmonic Co-Commission Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 7:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 8:00pm 8:00pm unless otherwise noted unless otherwise noted Conductor Guest Artists Program Esa-Pekka Leila Josefowicz violin RAVEL Mother Goose Suite NOV Salonen Esa-Pekka SALONEN Violin Concerto NOV OCT OCT NOV conductor (New York Concert Premiere) 5 30 31 1 2 SIBELIUS Symphony No. 5 (11:00am) Bernard Miah Persson soprano J.S. BACH Cantata No. 51, Jauchzet Labadie Stephanie Blythe Gott in allen Landen! conductor mezzo-soprano HANDEL “Let the Bright Seraphim” Frédéric Antoun tenor from Samson Andrew Foster- MOZART Requiem NOV NOV NOV Williams bass 7 8 9 Matthew Muckey trumpet New York Choral Artists Joseph Flummerfelt director Alan Gilbert Liang Wang oboe R. STRAUSS Also sprach Zarathustra conductor Glenn Dicterow, violin NOV Christopher ROUSE Oboe Concerto NOV NOV NOV 15 (New York Premiere) 19 14 16 R. STRAUSS Don Juan (2:00pm) Glenn Dicterow, violin Alan Gilbert Paul Appleby tenor BRITTEN Serenade for Tenor, Horn, conductor Philip Myers horn and Strings Kate Royal soprano BRITTEN Spring Symphony Sasha Cooke mezzo-soprano NOV NOV NOV New York Choral Artists 21 22 23 Joseph Flummerfelt director Brooklyn Youth Chorus Dianne Berkun- Menaker director Alan Gilbert Paul Appleby tenor MOZART Symphony No. -

Union Describes Graft at UCSD Clinics

Their walls are bllul of ca""o"balls, Their mollo is, "Doli 'I' .read 0" me. " - Robert Hunter Photos: Malcolm Smith Patient's Charges Union Describes Graft at UCSD Clinics Inside: The San Diego Union published an A man Layne accused of tampering unknowingly purchased stolen property article Friday containing allegations of with urine samples, who became a from a patient two years ago . Fiction by McCarty bribery and corruption at San Diego area counselor and later assi stant director of methadone clinics operated by the UCSD the I ndia Street clinic before losing his I n addition, Layne said he and his WIfe, Top Ten Books Medical School. job recently, admitted he had done so. also an addict, had contributed at the Softball Playoffs The man, Peter Cortez, 45/ told the Market and Harbison-5treet facilities to a The allegations were made by a Union that drug dealing between fund that would supposedly help supply patient, I 36-year-<>ld Michael Layne, a patients and counselors is common at all coffee and soft drinks for the clinics heroin addict for 15 years who now takes the clinics, and that patients who want Layne said he had discovered later that methadone, a drug that in most patients more methadone can obtain a recom the county pays for the coffee at the acts as a substitute for heroin. mendation for same from a counselor he clinics, and that he suspects the money has paid. " went into the pockets of clinic per Layne said, "It is a county policy to Cortez said payoffs come in money, sonneL" administer low doses of methadone to all drugs, favors, and sex. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

The Rice Thresher

Athletics Review Committee members v , * ?: Ralph O'Connor Troy Squires W.G. Characklis Catherine Hannah Richard Chapman Ira Gruber John Anderson Pro-athletic sentiment dominates open meeting by BARRY JONES questions and suggestions afford to compete? At the profitable one. revenue program. from members of the Rice meeting, it was never made The committee has studied One of the more pervasive The University Athletics community. The committee clear whether that was the sample budgets from several topics was the "sheltered Review Committee held an was formed by Dr. Hacker- committee's purpose, or schools, some of which have program." a major which is open meeting in Sewall Hall man. Most people have whether the question was if dropped athletics, some of open only to varsity athletes Monday night. The purpose of assumed that the underlying Rice should have an athletic which have cut back and even and which might be below the meeting was to field motive was financial: can Rice program at all, even a one that conducted a non- normal university standards. The Commerce Department Rice's entry in the sheltered program field, is currently being phased out. The consensus was that Rice should not operate under an academic double standard; the rice thresher also, the athlete should not be thursday, march 18, 1976 volume 63, number 44 herded into a program he didn't particularly care for just to keep his eligibility up. It was also suggested that Rice turns SA concurs with report, approves Pierce off many recruits because there is no actual business by KIM D. -

August 30, 2000 Issue 1

tirije Volume 50 August 30, 2000 Issue 1 Democratic Gore/ Welcome, Freshmen! ( See^Kbe ifiletcr's Lieberman ticket must-have Guide to debuts in Nashville Survival at TSU Tennessee State University Pages 8-9 Page 6 IS^ectsure Stz^dent Opirtion. and Sentiment 3 President replaced due to post-election grades Peek backs away from SGA office, stipulation limelight "\ am a broken soldier, my spirit is broken" -Peek By Hillary S. Condon Community View Editor President-elect Marc Anthony Peek will not be allowed to PHOTO BY JOHN ]. CARROLL COURTESY OF CHRISTOPHER BERRY take an official student government office at Tennessee State (Left) Marc Anthony Peek last winter, as a soldier for the TIME IS NOW STUDENT University. He came close last spring, when he was elected as presi MOVEMENT. (Right) Christopher Berry, who will soon be inaugurated as president of dent of the Student Government Association. the Student Government Association for 2000-01. However, at the end of the spring semester, his grades pre vented him from passing posi-certificalion requirements, and now, runner-up Christopher Berry w/Jl take the helm. Berr}^ ready for actiofi^ sets ^ Many say he was elected because of his outspoken attitude and representation of TSU's stipulation of settlement, but Peek said he was backing down from the attention he has garnered as an activist inauguration date for Aug. 3^ in the past as well as his elected office. "I am a broken soldier," he said. "My spirit is broken." \y Henderson Hill HI "I want people who are interested m He also said that he finds it difficult to be seen on campus 'Community View Writer being SGA president to come and talk to me"' because of his mistakes, and feels the pressure every time he is more," Berry said. -

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

Marshall University Music Department Presents

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar All Performances Performance Collection Fall 11-7-2008 Marshall University Music Department Presents, Music Alive Series, Graffe trS ing Quartet, Štĕpán Graffe, violin, Lukáš Bednařik, violin, Lukáš Cybulski, viola, Michal Hreno, violoncello, with, Michiko Otaki, piano Michiko Otaki Štĕpán Graffe Lukáš Bednařik Lukáš Cybulski Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Otaki, Michiko; Graffe, Štĕpán; Bednařik, Lukáš; and Cybulski, Lukáš, "Marshall University Music Department Presents, Music Alive Series, Graffe trS ing Quartet, Štĕpán Graffe, violin, Lukáš Bednařik, violin, Lukáš Cybulski, viola, Michal Hreno, violoncello, with, Michiko Otaki, piano" (2008). All Performances. 752. http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf/752 This Recital is brought to you for free and open access by the Performance Collection at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Performances by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DEPARTMENT of MUSIC Program String Quartet in g min.or, Franz Joseph Haydn op. 74, no. 3 ("Rider") (1732-1809) Allegro moderate MUSIC Largo assai Menuetto: Allegretto Finale: Allegro con brio presents the Quintet for Piano and Strings Robert Schumann Music Alive Series in E-flat major, op. 44 (1810-1856) Allegro brillante In modo d'una marcia GRAFFE STRING QUARTET Scherzo: Molto vivace Stepan Graffe, violin Allegro ma non troppo Lukas Bednarik, violin Lukas Cybulski, viola Michiko Otaki, piano Michal Hreno, violoncello with Michiko Otaki, piano Friday, November 7, 2008 Exclusive Management for the First Presbyterian Church GRAFFE QUARTET and MICHIKO OTAKI: 12:00 p.m. -

Tributaries 2013

1 2 TRIBUTARIES Tributaries 2012-2013 Staff Editors-in-Chief: Ian Holt and Deidra Purvis Fiction Editor: Chase Eversole Nonfiction Editor: Emily O’Brien Poetry Editor: Andrew Davis Art & Design Editor: Kaylyn Flora Copy Editor: Chase Eversole Faculty Advisors: Beth Slattery and Tanya Perkins 3 Our Mission Ridicule is the tribute paid to the genius by the mediocrities. ––Oscar Wilde Tributaries is a student-produced literary and arts journal published at Indiana University East that seeks to publish invigorating and multifaceted fiction, nonfiction, poetry, essays, and art. Our modus operandi is to do two things: Showcase the talents of writers and artists whose work feeds into a universal body of creative genius while also paying tribute to the greats who have inspired us. We accept submissions on a rolling basis and publish on an annual schedule. Each edition is edited during the fall and winter months, which culminates with an awards ceremony and release party in the spring. Awards are given to the best pieces submitted in all categories. Tributaries is edited by undergraduate students at Indiana University East. 4 TRIBUTARIES Table of Contents Art “Arty art” Danielle Standley Covers “See The Love Pt. 1” Jami Dingess 7 “Never Knew Love ‘Til Now” Jami Dingess 49 “See The Love Pt. 2” Jami Dingess 75 “Monsters in Paradise” Jami Dingess 100 Fiction “The Right Hand Pocket” Ryland McIntyre 9 “Book ‘Em” Krisann Johnson 12 “Nude” Brittany Hudson 14 “The Enemy Within” Lynn Loring 19 “Vance Grafton” Heather Barnes 20 “Part One: The Sock Bandits” -

N Ew Y O R K F Lu T E F a Ir 2021

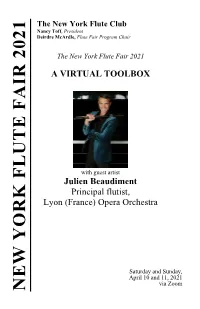

The New York Flute Club Nancy Toff, President Deirdre McArdle, Flute Fair Program Chair The New York Flute Fair 2021 A VIRTUAL TOOLBOX with guest artist Julien Beaudiment Principal flutist, Lyon (France) Opera Orchestra Saturday and Sunday, April 10 and 11, 2021 via Zoom NEW YORK FLUTE FAIR 2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS NANCY TOFF, President PATRICIA ZUBER, First Vice President KAORU HINATA, Second Vice President DEIRDRE MCARDLE, Recording Secretary KATHERINE SAENGER, Membership Secretary MAY YU WU, Treasurer AMY APPLETON JEFF MITCHELL JENNY CLINE NICOLE SCHROEDER RAIMATO DIANE COUZENS LINDA RAPPAPORT FRED MARCUSA JAYN ROSENFELD JUDITH MENDENHALL RIE SCHMIDT MALCOLM SPECTOR ADVISORY BOARD JEANNE BAXTRESSER ROBERT LANGEVIN STEFÁN RAGNAR HÖSKULDSSON MICHAEL PARLOFF SUE ANN KAHN RENÉE SIEBERT PAST PRESIDENTS Georges Barrère, 1920-1944 Eleanor Lawrence, 1979-1982 John Wummer, 1944-1947 John Solum, 1983-1986 Milton Wittgenstein, 1947-1952 Eleanor Lawrence, 1986-1989 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1952-1955 Sue Ann Kahn, 1989-1992 Frederick Wilkins, 1955-1957 Nancy Toff, 1992-1995 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1957-1960 Rie Schmidt, 1995-1998 Paige Brook, 1960-1963 Patricia Spencer, 1998-2001 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1963-1964 Jan Vinci, 2001-2002 Maurice S. Rosen, 1964-1967 Jayn Rosenfeld, 2002-2005 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1967-1970 David Wechsler, 2005-2008 Paige Brook, 1970-1973 Nancy Toff, 2008-2011 Eleanor Lawrence, 1973-1976 John McMurtery, 2011-2012 Harold Jones, 1976-1979 Wendy Stern, 2012-2015 Patricia Zuber, 2015-2018 FLUTE FAIR STAFF Program Chair: Deirdre McArdle -

Athletic Heritage

R Athletic Heritage Athletic Highlights • Morris Almond, was the 25th pick in the • Rice has won individual national titles in • The first NCAA team championship for first round by the Utah Jazz in the 2007 men’s tennis (two singles and two doubles), Rice, occurred in 2003, when the Owls won NBA Draft. He became the first Rice Owl to women’s tennis (doubles), men’s track and the College World Series. be selected in the first round since Ricky field and women’s track and field. Pierce was the 18th overall pick in the 1982 • The 1946 football Owls were Southwest NBA Draft by the Detroit Pistons. Almond is • The Owls have won a total of 75 Conference co-champions and went on to one of 20 men’s basketball players to play conference titles. defeat Tennessee in the Orange Bowl. professionally since 1992. • 495 Owls have earned All-America • In 2000, Rice won an unprecedented • Team captain Larry Izzo has won three honors. six Western Athletic Conference titles. Super Bowl rings as a member of the New The Owls were victorious in women’s England Patriots. More than 50 Owls have • Rice has been represented at 11 Olympics basketball, men’s and women’s cross played in the NFL. by 20 different athletes, dating back to the country, women’s indoor and outdoor track 1928 Amsterdam Olympics. and field, and baseball. • Rice’s women’s basketball team has been to the “Big Dance” twice after winning the • A total of 16 Owls have been drafted in 2000 and 2005 WAC Championship to earn the first round by Major League Baseball the league’s NCAA automatic bid.