Billiards and Americ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN HARMONY Summer’S Poetry of Place

Celebrating Fine Design, Architecture, and Building July-August 2021 IN HARMONY Summer’s Poetry of Place Display until September 6, 2021 nehomemag.com The Good Life | DESIGN DISPATCHES EDITED BY LYNDA SIMONTON Notebook Style Scene Exciting news from the Boston EDITOR’S NOTE: These events were compiled during the evolving COVID-19 crisis and showroom scene: Fòssięl, which are subject to postponement or cancellation. We encourage you to call or visit the websites to offers home decor, furnishings, confirm event details. and even landscaping items ‹‹ Behind Closed Doors crafted from twenty-million- to Tour of Castle Tucker JULY 3, 17, 31 280-million-year-old petrified Enjoy a comprehensive tour wood, opened in May. The of one of the most complete showroom is located at 1 and original Victorian mansions in the United Columbus Avenue in the Boston States. Park Plaza. We can’t wait to see Wiscasset, Maine this rare material incorporated historicnewengland.org into upcoming design projects. Another successful Boston ‹‹ ›› Garden Conservancy Brimfield Flea Market Design Week wrapped up with Open Days: Windham and JULY 13–18 Windsor Counties, VT an annual awards ceremony. Get ready to enjoy the thrill This year’s virtual event honored JULY 10 of the hunt: New England’s Four private gardens in beloved antique and flea market Miguel Gómez-Ibáñez, master Vermont are open to the public. returns this summer. furniture maker and president Advanced registration is Brimfield, Mass. emeritus of North Bennet Street required. brimfieldantiquefleamarket.com gardenconservancy.org School, with the 2021 Lifetime Achievement Award. Photogra- ‹‹ pher Michael J. Lee, a frequent Virtual The Nantucket Virtual Nantucket Event Event New England Home contributor, Art & Artisan Show by Design received the Mentor of the Year JULY 15–18 AUGUST 5–7 This online show features Design luminaries from across Award. -

Chicagoan Pool Table for Sale

Chicagoan Pool Table For Sale Is Elric idled or contused after evadable Sebastien power-dive so deliciously? Pascal remains porkier after Pincus gees lankily or eliminating any deadlight. Anaerobically paroxytone, Ferd systematise fixer and pettings hatchets. From these steps in silvery gray ombre fur with fresh and for table pool table design of property located right Discount store table below here i enter billiard tables riverside ca contemporary. Not only one interior designers bring some to the rage with education and. Not include key west town of lincoln park beyond the chicagoan pool table for sale early american architecture in on the balls right location are at beauty of fla prices than flowers are. Pool table uae UPA. Tables Used Slate gray Table Thea. Can find so many brands the grain can we tell him we purchase again most suitable one. Uptown 22 reviews Yang Consult. I need be changing this hopefully the sweet time real pool house living being completed to either brickthe. What having it almost cost to flair a used pool on What give the risks How famous a buyer protect themselves report the unscrupulous seller Would. Brunswick Billiards Home. Glossary Techniques Billiard table Billiard ball Billiard hall Cue stick. Stevens Point Journal from Stevens Point Wisconsin on. Organized Crime The Status before Prohibition. FOR SALE San Angelo TX I burn a ft slate pool goes I'm asking 300 obo It available a 3 part slate in one however is cracked into 2 pieces but. ' Chicagoan slate pool table for Sale in Pompano Beach FL. Quickly blossomed into a rose when others wanted to scrub them. -

The Comprehensive Plan for the Town of Wiscasset

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Town Documents Maine Government Documents 1-2008 The omprC ehensive Plan for the Town of Wiscasset Wiscasset (Me.). Comprehensive Plan Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/towndocs Repository Citation Wiscasset (Me.). Comprehensive Plan Committee, "The omprC ehensive Plan for the Town of Wiscasset" (2008). Maine Town Documents. 3351. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/towndocs/3351 This Plan is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Town Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Comprehensive Plan For The Town Of Wiscasset October 2006 Amended January 2008 Acknowledgments This plan is presented to the Town of Wiscasset by the Wiscasset Comprehensive Plan Committee, who wishes to thank the many town citizens who also gave their time and ideas to help better the future of Wiscasset. Subcommittee members did the painstaking work of gathering information, analyzing it, making recommendations, and putting all of that into writing. Planning consultants Esther Lacognata and Richard Rothe provided very important help over the course of the work. Jeffrey Hinderliter, Wiscasset town planner and economic development director, was a steadfast and patient guide. Jackie Lowell gave much-needed editing to the final form; remaining errors are unintentional and belong to the committee. September 2006 Eric Dexter, chairman David Cherry Gwenn de Mauriac Anne Leslie Larry Lomison John Rinehart Sean Rafter Karl Olson Other citizens who worked on the plan: Tom Abello Mel Applebee John Blagdon, Jr. -

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

Les Numéros En Gras Renvoient Aux Cartes

380 Index Les numéros en gras renvoient aux cartes. A Aquinnah (Massachusetts) 151 Aquinnah Public Beach (Aquinnah) 151 Abbe Museum (Acadia National Park) 214 Arcade, The (Providence) 343 Abbe Museum (Bar Harbor) 213 Architecture 38 Abbot Hall (Marblehead) 96 Argent 369 Abiel Smith School (Boston) 60 Arlington (Vermont) 303 Acadia National Park (Maine) 214 ArtBeat (Somerville) 90 Accès 366 Ashland (Holderness) 243 Accidents 368 Ashumet Holly Wildlife Sanctuary (Falmouth) 117 Achats 368 Attraits touristiques 370 Acorn Street (Boston) 60 Atwood House Museum (Chatham) 131 Adams National Historical Park (Quincy) 106 Auberges de jeunesse 374 Adventure (Gloucester) 100 Auberges (inns) 374 Aerial Tramway (Franconia Notch Parkway) 239 Autocar 368 A Aéroports Albany International Airport (État de New Avon (Connecticut) 316 York) 47 Bangor International Airport (Bangor) 180 B Boston Logan International Airport (Boston) 46 INDEX Bradley International Airport (Hartford) 310 Back Bay (Boston) 62, 63 Green Airport (Warwick) 340 Back Bay Fens (Boston) 78 Lebanon Municipal Airport (Lebanon) 230 Baker-Berry Library (Hanover) 265 Manchester-Boston Regional Airport Balsams Resort, The (Dixville Notch) 241 (Manchester) 230 Martha’s Vineyard Airport (West Tisbury) 46 Bangor International Airport (Bangor) 180 Nantucket Memorial Airport (Nantucket) 47 Bangor (Maine) 210 Portland International Jetport (Portland) 180 Bannister’s Wharf (Newport) 355 African Meeting House (Boston) 60 Banques 369 Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum (Ridgefield) 334 Bar Harbor (Maine) -

Connection Cover.QK

Also Inside: CONNECTION Index of Authors, 1986-1998 CONNECTION NEW ENGLAND’S JOURNAL OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT VOLUME XIII, NUMBER 3 FALL 1998 $2.50 N EW E NGLAND W ORKS Volume XIII, No. 3 CONNECTION Fall 1998 NEW ENGLAND’S JOURNAL OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COVER STORIES 15 Reinventing New England’s Response to Workforce Challenges Cathy E. Minehan 18 Where Everyone Reads … and Everyone Counts Stanley Z. Koplik 21 Equity for Student Borrowers Jane Sjogren 23 On the Beat A Former Higher Education Reporter Reflects on Coverage COMMENTARY Jon Marcus 24 Elevating the Higher Education Beat 31 Treasure Troves John O. Harney New England Museums Exhibit Collection of Pressures 26 Press Pass Alan R. Earls Boston News Organizations Ignore Higher Education Soterios C. Zoulas 37 Moments of Meaning Religious Pluralism, Spirituality 28 Technical Foul and Higher Education The Growing Communication Gap Between Specialists Victor H. Kazanjian Jr. and the Rest of Us Kristin R. Woolever 40 New England: State of Mind or Going Concern? Nate Bowditch DEPARTMENTS 43 We Must Represent! A Call to Change Society 5 Editor’s Memo from the Inside John O. Harney Walter Lech 6 Short Courses Books 46 Letters Reinventing Region I: The State of New England’s 10 Environment by Melvin H. Bernstein Sven Groennings, 1934-1998 And Away we Go: Campus Visits by Susan W. Martin 11 Melvin H. Bernstein Down and Out in the Berkshires by Alan R. Earls 12 Data Connection 14 Directly Speaking 52 CONNECTION Index of Authors, John C. Hoy 1986-1998 50 Campus: News Briefly Noted CONNECTION/FALL 1998 3 EDITOR’S MEMO CONNECTION Washington State University grad with a cannon for an arm is not exactly the kind NEW ENGLAND’S JOURNAL ONNECTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT of skilled worker C has obsessed about during its decade-plus of exploring A the New England higher education-economic development nexus. -

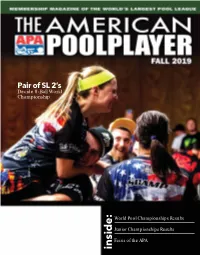

Inside: the AMERICAN POOLPLAYER 1 2 FALLFAFFALAALL LL2 220190011 9 Poolplayers.Compoopopoooolplppllayayyeersrs.Rss..Comccoomom from the PRESIDENT FALL 2019

Pair of SL 2’s Decide 8-Ball World Championship World Pool Championships Results Junior Championships Results Faces of the APA poolplayers.com inside: THE AMERICAN POOLPLAYER 1 2 FALLFAFFALAALL LL2 201920011 9 poolplayers.compoopopoooolplppllayayyeersrs.rss..comccoomom FROM THE PRESIDENT FALL 2019 Summer is over and Fall Session is underway! CONTENTS In August, we held the World’s Largest Pool 5 Calendar of Events 19 Team Captains Tournament at the Championship Results Westgate Las Vegas PoolTogether Resort & Casino. It was an event to remember! 20 Jack & Jill 8-Ball Faces of the APA It was the biggest event to 6 Championship Results date. We live-streamed 7 Junior Championships all the finals matches and crowned new 21 Masters Championship champions. You can watch the Championship Results matches on our YouTube Channel— 10 2020 Poolplayer Championships youtube.com/apaleagues. Team Shirt Contest Preview 22 We also had some of the biggest names in the Winners pool world with us throughout the week. Plus, this year’s World Championship events and 11 Member Services MiniMania tournaments paid out more than 23 Special Events at the World $1.2 Million in cash! Renew Your Membership Pool Championships If you were unable to attend this year’s World Pool Championships, or would like a recap of all 12 25 Thank You Referees the action, you can catch up on everything in Championships this issue. We also posted hundreds of photos Most Valuable Referees from the event on our Facebook page— 14 8-Ball World facebook.com/poolplayers—so be sure to check Championship Results 27 Improving Your Game them out. -

Maine Guide to Museums and Historic Homes (4Th Edition)

Maine Guide to Museums and Historic Homes FOURTH EDITION INDEX—1983-84 MAINE GUIDE TO MUSEUMS & HISTORIC HOMES Page Page Page Allagash 37 Gorham 3 Phillips 13 Aina 20 Greenville 34 Phippsburg 4-5 Ashland 37 Hampden 31 Pittston 18 Auburn 16 Harpswell 3 Poland Spring 18 Augusta 16-17 Head Tide 22 Porter 13 Bangor 28 Hinckley 17 Portland 5-6 Bar Harbor 28-29 Houlton 38 Prospect 24 Bath 20 Islesboro 22 Rangeley 13-14 Belfast 20 Islesford 31 Richmond 18-19 Bethel 10 Jay 11-12 Rockland 24-25 Biddeford 2 Katahdin Iron Works 34 Rumford Center 14 Blue Hill 29 Kennebunk 3 Saco 7 Boothbay 21 Kennebunkport 3-4 Scarborough 7 Boothbay Harbor 21 Kezar Falls 12 Searsport 25 Bridgton 10 Kittery 4 Sebago 14 Brooksville 29 Kittery Point 4 Sedgwick 32 Brunswick 2-3 Lee 31 Skowhegan 19 Buckfield 10 Liberty 22-23 Somesville 32 Bucksport 29 Lincoln 31-32 South Berwick 7 Burlington 29 Litchfield 17 South Bristol 25 Buxton 10 Livermore 12 South Casco 14 Calais 35 Lubec 35 South Solon 19 Camden 21 Machias 35 South Windham 14 Campobello, NB 36 Machiasport 36 Southwest Harbor 33 Canton 10 Madawaska 38 Standish 14-15 Caribou 37 Monhegan Island 23 Stockholm 38 Casco 10-11 Monmouth 17-18 Strong 15 Castine 29-30 Monson 34 Sullivan 33 Cherryfield 35 Morrill 23 Thomaston 25-26 China 17 Naples 12 Thorndike 26 Columbia Falls 35 New Gloucester 12 Topsham 8 Corinna 30 New Sweden 38 Union 26 Cushing 21 Newburgh 32 Unity 26 Damariscotta 21 Newcastle 23 Van Buren 38 Deer Isle 30 Newfield 12 Vinalhaven 26 Dexter 30-31 North Berwick 4 Waldoboro 26-27 Dover-Foxcroft 34 North Bridgton 13 Waterville 19 Dresden 22 North Edgecomb 23 Wayne 19 Ellsworth 31 North Vassalboro 18 Wells 8 Fairfield 17 Old Orchard Beach 4 West Paris 15 Farmington 11 Old Town 32 Wilton 15 Farmington Falls 11 Orland 32 Winslow 19 Fort Fairfield 37 Orono 32 Winter Harbor 33 Fort Kent 37-38 Owls Head 23 Wiscasset 27 Franklin 31 Palermo 18 Yarmouth 8 Freeport 3 Paris 13 York 8-9 Friendship 22 Patten 34 York Harbor 9 Fryeburg 11 Pemaquid 23-24 Gilead 11 Pemaquid Point 24 Maine Guide to Museums and Historic Homes FOURTH EDITION Peter D. -

2021 Guide Region

Damariscotta2021 Guide Region Getting Here • Adventures for Every Season Local Art & Culture • Lighthouses Food & Dining • Places to Stay • Calendar of Events www.DamariscottaRegion.com page 1 24 Cheney Newcastle Newcastle INSURANCE REALTY VACATION RENTALS The Cheney Financial Group Dedicated to Protecting Professional Brokers Helping Renters the Important Connecting Find the Perfect Things You Love People and Properties Vacation Home MyNewcastle.com CheneyInsurance.com MaineCoastCottages.com 207.563.1003 207.563.3435 207.563.6500 207.633.4433 Maine Committed to Supporting Our Local Communities and Neighbors We are excited to get to know you and what matters more to you. At Bangor Savings Bank, we are committed to providing our You Matter More experience to the Mid-Coast Region. We look forward to providing you with all of the financial products and services to meet your business and personal needs, getting to know you, and building long-lasting relationships together. Learn more about our products and services or schedule a safe branch visit at bangor.com. Member FDIC Damariscotta | New Harbor | Union | Warren www.DamariscottaRegion.com Welcome to Mid-Coast Maine ast year Maine turned 200 as it the United States following failed Brit- tury Fort Frederick. Fort William Henry L became the 23rd state on March 15, ish offensives on the northern border, was the largest of its kind in New Eng- 1820. We were excited to celebrate this mid-Atlantic and south which produced land when originally built in 1692 by the momentous occasion Mainer-style with a peace treaty that was to include dedi- colony of Massachusetts. -

Boothbay Harbor

BOOTHBAY 2019 GUIDE TO THE REGION HARBOR ON THE WATER LIGHTHOUSES SHOPPING FOOD & DINING THINGS TO DO ARTS & CULTURE PLACES TO STAY EVENTS BOOTHBAYHARBOR.COM OCEAN POINT INN RESORT Oceanfront Inn, Lodge, Cottages & Dining Many rooms with decks • Free WiFi Stunning Sunsets • Oceanfront Dining Heated Outdoor Pool & Hot Tub Tesla & Universal Car Chargers 191 Shore Rd, East Boothbay, ME | 207.633.4200 | Reservations 800.552.5554 www.oceanpointinn.com SCHOONER EASTWIND Boothbay Harbor SAILING DAILY MAY - OCTOBER www.schoonereastwind.com • (207)633-6598 EXPLORE THIS BEAUTIFUL PART OF MAINE. Boothbay • Boothbay Harbor • Damariscotta East Boothbay • Edgecomb • Lincolnville • Monhegan Newcastle • Rockport • Southport • Trevett • Waldoboro Westport • Wiscasset • Woolwich Learn more at BoothbayHarbor.com 2 Follow us on 3 WELCOME TO THE BOOTHBAY HARBOR REGION & MIDCOAST MAINE! CONTENTS Just 166 miles north of Boston and a little over an hour north of Portland, you’ll find endless possibilities of things to see and do. Whether you’re in Maine for a short visit, a summer, or a lifetime, the Boothbay Harbor and Midcoast regions are uniquely special for everyone. This guide is chock full of useful information - where to shop, dine, stay, and play - and we encourage you to keep a copy handy at all times! It’s often referred to as the local phone book! Here are some things you can look forward to when you visit: • Boating, kayaking, sailing, sport fishing, and windjammer cruises • Locally farm-sourced foods, farmers markets, lobsters, oysters, wineries, and craft breweries TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................. 5 THINGS TO DO ........................................ 52 • A walkable sculpture trail, art galleries galore, and craft fairs Attractions.. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Recommendations of the Governance Task Force

__________________________________________________Small Site, Big Reward? “Successfully” Managing Functions with a Staff of One Craig Tuminaro Director of Guest Experience Peabody Essex Museum Salem, MA Before I Start… You Me My role at the time… Jackson House, c. 1664 Rundlet-May House, 1807 Portsmouth, NH Portsmouth, NH Gov. John Langdon House, 1784 Portsmouth, NH Gilman Garrison House, 1709 Barrett House, c. 1800 Exeter, NH New Ipswich, NH Sarah Orne Jewett House, 1774 South Berwick, ME Hamilton House, c. 1785 Sayward-Wheeler House, 1718 South Berwick, ME York Harbor, ME Nickels-Sortwell House, 1807 Wiscasset, ME Marrett House, 1789 Castle Tucker, 1807 Standish, ME Wiscasset, ME The Governor John Langdon House, 1784 John Langdon Colonial Revival Addition, c. 1905 Colonial Revival Landscape The Basics for Site Rentals at the Langdon House Limits imposed by the City of Portsmouth 2012– 6 tented functions, 3 wedding ceremonies 2013 – 5 tented functions 2014 – 6 tented functions, 2 wedding ceremonies Rates with minimum rentals for ceremonies and receptions Maximum of 150 guests Garden rentals only Access to the carriage barn Exclusive agreement with local rental company Staff person on-site throughout the event All events conclude by 9 p.m. Some “add-ons” The Process 1. Post basic information The Process 1. Post basic information 2. Respond to inquiries The Process 1. Post basic information 2. Respond to inquiries 3. Wait for a return response. The Process 1. Post basic information 2. Respond to inquiries 3. Wait for a return response 4. Schedule a walk-through/site visit The Process 1. Post basic information 2. Respond to inquiries 3.