Towards a Microeconomics of Growth1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

with Open Texts Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine VERSION 2017 – REVISION B ADAPTABLE | ACCESSIBLE | AFFORDABLE Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-SA) advancing learning Champions of Access to Knowledge OPEN TEXT ONLINE ASSESSMENT All digital forms of access to our high- We have been developing superior on- quality open texts are entirely FREE! All line formative assessment for more than content is reviewed for excellence and is 15 years. Our questions are continuously wholly adaptable; custom editions are pro- adapted with the content and reviewed for duced by Lyryx for those adopting Lyryx as- quality and sound pedagogy. To enhance sessment. Access to the original source files learning, students receive immediate per- is also open to anyone! sonalized feedback. Student grade reports and performance statistics are also provided. SUPPORT INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTS Access to our in-house support team is avail- Additional instructor resources are also able 7 days/week to provide prompt resolu- freely accessible. Product dependent, these tion to both student and instructor inquiries. supplements include: full sets of adaptable In addition, we work one-on-one with in- slides and lecture notes, solutions manuals, structors to provide a comprehensive sys- and multiple choice question banks with an tem, customized for their course. This can exam building tool. include adapting the text, managing multi- ple sections, and more! Contact Lyryx Today! [email protected] advancing learning Principles of Microeconomics an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine Version 2017 — Revision B BE A CHAMPION OF OER! Contribute suggestions for improvements, new content, or errata: A new topic A new example An interesting new question Any other suggestions to improve the material Contact Lyryx at [email protected] with your ideas. -

Regional Economics: Understanding the Third Great Transition

REGIONAL ECONOMICS: UNDERSTANDING THE THIRD GREAT TRANSITION Paul Krugman September 2019 Memo to young economists: the transition from fiery upstart to old fuddy-duddy elder statesman sneaks up on you. One day, it seems, you’re trying to turn everything upside down; the next thing you know you’ve turned into one of those old guys whose response to any new idea is “It’s trivial, it’s wrong, and I said it in 1962.” Sure enough, in a couple of weeks I’m giving the luncheon keynote speech at a Boston Fed conference on America’s growing regional disparities, basically providing a break and maybe some inspiration in between presentations by real researchers. The brief talk doesn’t require a paper, and I am not someone who reads prepared speeches. But I thought I might take the occasion to write down a few thoughts on the subject. Basically, I want to make three points: 1. The regional divergence we’ve seen since around 1980 probably isn’t trivial or transient. Instead, it reflects a shift in the underlying logic of regional growth — the kind of shift that theories of economic geography predict will happen now and then, when the balance between forces of agglomeration and those of dispersion crosses a tipping point. 2. This isn’t the first time this kind of transition has happened. In fact, it’s the third such shift in the history of the U.S. economy, which went through earlier eras of both regional divergence and regional convergence. 3. There are pretty good although not ironclad arguments for “place-based” policies to limit regional divergence. -

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — Preface to Game Theory

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — prefacetogametheory (Mar 11, 2012) School of Economics The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya Oligopoly is a market in which only a few firms compete with one another, • and entry of new firmsisimpeded. The situation is known as the Cournot model after Antoine Augustin • Cournot, a French economist, philosopher and mathematician (1801-1877). In the basic example, a single good is produced by two firms (the industry • is a “duopoly”). Cournot’s oligopoly model (1838) — A single good is produced by two firms (the industry is a “duopoly”). — The cost for firm =1 2 for producing units of the good is given by (“unit cost” is constant equal to 0). — If the firms’ total output is = 1 + 2 then the market price is = − if and zero otherwise (linear inverse demand function). We ≥ also assume that . The inverse demand function P A P=A-Q A Q To find the Nash equilibria of the Cournot’s game, we can use the proce- dures based on the firms’ best response functions. But first we need the firms payoffs(profits): 1 = 1 11 − =( )1 11 − − =( 1 2)1 11 − − − =( 1 2 1)1 − − − and similarly, 2 =( 1 2 2)2 − − − Firm 1’s profit as a function of its output (given firm 2’s output) Profit 1 q'2 q2 q2 A c q A c q' Output 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 To find firm 1’s best response to any given output 2 of firm 2, we need to study firm 1’s profit as a function of its output 1 for given values of 2. -

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics Global Citizenship Program ECON 3020 Intermediate Microeconomics (3) Knowledge Areas (....) This course covers advanced theory and applications in microeconomics. Topics include utility theory, consumer and ARTS Arts Appreciation firm choice, optimization, goods and services markets, resource GLBL Global Understanding markets, strategic behavior, and market equilibrium. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. PNW Physical & Natural World ECON 3030 Intermediate Macroeconomics (3) QL Quantitative Literacy This course covers advanced theory and applications in ROC Roots of Cultures macroeconomics. Topics include growth, determination of income, employment and output, aggregate demand and supply, the SSHB Social Systems & Human business cycle, monetary and fiscal policies, and international Behavior macroeconomic modeling. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. Global Citizenship Program ECON 3100 Issues in Economics (3) Skill Areas (....) Analyzes current economic issues in terms of historical CRI Critical Thinking background, present status, and possible solutions. May be repeated for credit if content differs. Prerequisite: ECON 2000. ETH Ethical Reasoning INTC Intercultural Competence ECON 3150 Digital Economy (3) Course Descriptions The digital economy has generated the creation of a large range OCOM Oral Communication of significant dedicated businesses. But, it has also forced WCOM Written Communication traditional businesses to revise their own approach and their own value chains. The pervasiveness can be observable in ** Course fulfills two skill areas commerce, marketing, distribution and sales, but also in supply logistics, energy management, finance and human resources. This class introduces the main actors, the ecosystem in which they operate, the new rules of this game, the impacts on existing ECON 2000 Survey of Economics (3) structures and the required expertise in those areas. -

FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021

9/15/21 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021 Course # Class # Units Course Title Day Time Location Instruction Mode Instructor Limit 1078-001 20457 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 8:00-8:50 ECON 117 IN PERSON Bentz 47 1078-002 20200 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 6:30-7:20 ECON 119 IN PERSON Hurt 47 1078-004 13409 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Marein 71 1088-001 18745 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 6:30-7:20 HLMS 141 IN PERSON Zhou, S 47 1088-002 20748 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 8:00-8:50 HLMS 211 IN PERSON Flynn 47 2010-100 19679 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Keller 500 2010-200 14353 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Carballo 500 2010-300 14354 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Bottan 500 2010-600 14355 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Klein 200 2010-700 19138 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Gruber 200 2020-100 14356 4 Principles of Macroeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Valkovci 400 3070-010 13420 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 9:10-10:00 ECON 119 IN PERSON Barham 47 3070-020 21070 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 2:20-3:35 ECON 117 IN PERSON Chen 47 3070-030 20758 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 11:10-12:25 ECON 119 IN PERSON Choi 47 3070-040 21443 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 1:50-2:40 ECON 119 IN PERSON Bottan 47 3080-001 22180 3 Intermediate Macroeconomic Theory MWF 11:30-12:20 -

Doctor of Philosophy in Economics

ECO 6525 PUBLIC SECTOR ECONOMICS (3) Course Information Introduction to the public sector and the allocation of resources, emphasis on market failure and the economic role of government. ECO 6115 MICROECONOMICS I (3) (PR: ECO 6115) Microeconomic behavior of consumers, producers, and resource suppliers, price determination in output and factor markets, general ECO 6936 FORECASTING AND ECONOMIC TIME market equilibrium. (PR: ECO 3101, ECO 6405 or CI) SERIES (3) Study of time series econometrics estimation with applications to ECO 7116 MICROECONOMICS II (3) economic forecasting. (PR: ECO 6424) Topics in advanced microeconomic theory, including general equilibrium, welfare economics, intertemporal choice, uncertainty, ECO 6936 BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS (3) University of South Florida information, and game theory. (PR: ECO 6115) Survey of evidence on departures of economic agents from rationality. Topics include present-based preferences, reference College of Arts and Sciences ECO 6120 ECONOMIC POLICY ANALYSIS (3) dependence, and non-standard beliefs. (PR: ECO 6424) 4202 E. Fowler Avenue The application of economic theory to matters of public policy. (PR: ECO 3101) ECP 6205 LABOR ECONOMICS I (3) Tampa, FL 33620 Labor demand and supply, unemployment, discrimination in labor ECO 6206 MACROECONOMICS I (3) markets, labor force statistics. (PR: ECO 3101 or ECO 6115) Dynamic analysis of the determination of income, employment, prices, and interest rates. (PR: ECO 6405) ECP 7207 LABOR ECONOMICS II (3) Advanced study of labor economics including analysis of the wage Doctor of Philosophy ECO 7207 MACROECONOMICS II (3) structure, labor unions, labor mobility, and unemployment. (PR: Topics in advanced macroeconomic theory with a particular emphasis ECP 6205) on quantitative and empirical applications. -

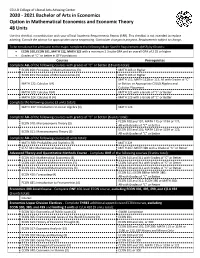

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

International Undergraduate Prospectus 2011 E at Du a R UNDERG Contents

International Undergraduate Prospectus 2011 Prospectus Undergraduate International UNDERGRAduATE Contents UWS AND YOU ..................... 1 Why choose UWS? . 2 Student Services and Facilities . 4 Teaching and Learning – a different style . 6 UWS Life – Where will you study? UWS campuses . 7 Bankstown campus . 8 Campbelltown campus . 10 Hawkesbury campus . 12 Nirimba (Blacktown) campus . 14 Parramatta campus . 16 Penrith campus . 18 Westmead precinct . 20 UWS Life Accommodation . 22 Preparing for life at UWS . 24 Your study destination . 26 Cost of living . 28 Working in Australia . 30 COURSE GUIDE .................... 31 Course and Career Index . 32 Agriculture, Horticulture, Food and Natural Sciences and Animal Science . 34 Arts, International Studies, Languages, Interpreting and Translation . 38 Business . 41 Communication, Design and Media . 49 Computing and Information Technology . 51 Engineering, Construction and Industrial Design . 54 Forensics, Policing and Criminology . 60 Health and Sport Sciences . 62 Law . 68 Medicine . 71 Natural Environment and Tourism . 72 Nursing . 76 Psychology . 78 Sciences . 80 Social Sciences . 85 Teaching and Education . 87 ADMISSION ....................... 91 Academic entry requirements . 92 Undergraduate coursework entry requirements and 2011 fees . 94 English language entry requirements . 100 UWSCollege – your pathway to UWS . 101 How to apply . 106 Important information . 108 International student undergraduate application form . 109 UWS and You U UWS AND YO Jasper Duineveld, Netherlands » Bachelor of Arts (Psychology) ‘My experience at UWS has taught me that there are so many possibilities in life and every part has a positive outlook. The people and especially the lecturers at UWS are great, they are always willing to help you out.’ UWS has been recognised for outstanding contributions to student learning at the 2010 national Australian Learning and Teaching Council (ALTC) Awards. -

Principles of Microeconomics

PRINCIPLES OF MICROECONOMICS A. Competition The basic motivation to produce in a market economy is the expectation of income, which will generate profits. • The returns to the efforts of a business - the difference between its total revenues and its total costs - are profits. Thus, questions of revenues and costs are key in an analysis of the profit motive. • Other motivations include nonprofit incentives such as social status, the need to feel important, the desire for recognition, and the retaining of one's job. Economists' calculations of profits are different from those used by businesses in their accounting systems. Economic profit = total revenue - total economic cost • Total economic cost includes the value of all inputs used in production. • Normal profit is an economic cost since it occurs when economic profit is zero. It represents the opportunity cost of labor and capital contributed to the production process by the producer. • Accounting profits are computed only on the basis of explicit costs, including labor and capital. Since they do not take "normal profits" into consideration, they overstate true profits. Economic profits reward entrepreneurship. They are a payment to discovering new and better methods of production, taking above-average risks, and producing something that society desires. The ability of each firm to generate profits is limited by the structure of the industry in which the firm is engaged. The firms in a competitive market are price takers. • None has any market power - the ability to control the market price of the product it sells. • A firm's individual supply curve is a very small - and inconsequential - part of market supply. -

OECD Comparable and Other Selected Small Area Indicators

PROJECT FACT SHEET OECD comparable and other selected small area indicators Vision statement This project will develop a suite of indicators across a number of domains which can Project deliverables be used to assess and measure local community (SLA) socio-economic performance. * Review of the literature on social indicators These indicators will be accessible to urban researchers via the AURIN portal. * Benchmarked indicators comparable with OECD indicators for wellbeing at national level and the appropriate benchmarks to derive small Project overview area estimates Measures and benchmarks of local socio-economic performance are important * A final report containing a technical description of the modelling, a technical description of the tools for research and policy surrounding sustainable and effective communities. database including metadata and instructions The final set of indicators will be informed by the OECD Indicators project (Society on the service, user manual on how to use. at a Glance). The set of indicators will cover the same domains as Society at a Glance * Suite of social indicators available through the (general context; self sufficiency; equity; health; and social cohesion), and where AURIN portal possible will use similar indicators (see Figure 1). These indicators will be Fig.1 Conceptual model of OECD Comparable and Other Small Area Social Indicators for Australia project The AURIN Project is an initiative of the Australian Government being conducted as part of the Super Science Initiative and financed from the Education Investment Fund. The University of Melbourne is the Commonwealth-appointed Lead Agent of the AURIN Project PROJECT FACT SHEET OECD comparable and other selected small area indicators Project overview cont’d Team provided for Statistical Local Areas in Australia using the latest available data. -

COURSE OUTLINE ECON 100 Introduction to Microeconomics 3.0 CREDITS

APPLIED SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT School of Business and Leadership Fall, 2017 COURSE OUTLINE ECON 100 Introduction to Microeconomics 3.0 CREDITS PREPARED BY: Jennifer Moorlag DATE: August 31, 2017 APPROVED BY: DATE: APPROVED BY ACADEMIC COUNCIL: (date) RENEWED BY ACADEMIC COUNCIL: (date) ECON 100 Course Outline by Jennifer Moorlag is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License 2 APPLIED SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT Economics 100 3 Credits Fall, 2017 Introduction to Microeconomics INSTRUCTOR: Jennifer Moorlag, B.A, M.Ed. OFFICE HOURS: M/W 10am-noon F 9am-noon OFFICE LOCATION: A2412 CLASSROOM: A2402 E-MAIL: [email protected] TIME: M/W 8:30am-10:00am TELEPHONE: 867.668.8756 DATES: Sept 6 – Dec 21 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course discusses the terminology, concepts, theory, methodology and limitations of current microeconomic analysis. The course provides students with a theoretical structure to analyze and understand economics as it relates to individuals and businesses. In addition, it seeks to provide students with an understanding of how political, social and market forces determine and affect the Canadian economy. This introductory course explores the principles of production and consumption – and the exchange of goods and services – in a market economy. In particular, it compliments courses in the Business Administration program by highlighting the various market mechanisms that influence managerial decision-making. PREREQUISITES None EQUIVALENCY OR TRANSFERABILITY SFU ECON 103 (3)