Class and Tenancy Relations in Calcutta, 1914-1926 Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay & Ujaan Ghosh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

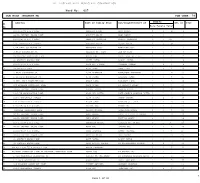

Ward No: 027 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 027 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 123/2/H/69 A P C ROAD ABHIJIT KUNDU BASU KUNDU 5 4 9 1 2 44/3A HARTAKI BAGAN LANE ABHIJIT MARIK AMAL MARIK 4 3 7 2 3 123/2/H/34 A P C ROAD ABHIJIT PRAMANIK PRADIP PRAMANIK 6 5 10+ 3 4 124/3 MANIKTALA STREET ABHISEK BARIK ASHOK BARIK 6 3 9 4 5 1/2A RAJA GOPIMOHAN ST. ABHISHEK GOUD BABLURAM GOUD 4 1 5 5 6 3 RAJA GOPIMOHAN ST. ABINASH KR. SHAW DEB KR SHAW 2 4 6 6 7 2A BASHNAB SAMMILANI LANE ADHIR DAS LATE DULAL CH. DAS 1 2 3 7 8 45 HARTAKI BAGAN LANE ADITI PATRA ASHOK PATRA 2 3 5 8 9 123/2/H/48 A P C ROAD AJAY KR. SONKAR SITARAM SONKAR 4 2 6 9 10 2A BARRICK LANE AJAY SHAW RAMA SHAW 2 4 6 10 11 3 RAJA GOPIMOHAN ST. AJIT KARMAKAR RAMESHWAR KARMAKAR 3 1 4 12 12 1/2A RAJA GOPIMOHAN ST. AJIT SINGH LACHHMI SINGH 3 3 6 13 13 9 REV. KALI BANERJEE ROW AKASH LAHA BONOMALI LAHA 2 1 3 14 14 2/A BASHNAB SAMMILANI LANE ALAK NAYEK LT PRADYUT NAYEK 1 4 5 15 15 44/3A HARTAKI BAGAN LANE ALHADI PATRA SWAPAN PATRA 4 2 6 16 16 19/1/1B MADAN MITRA LANE ALOK DEY DUTTA LATE GANESH CHANDRA DUTTA 1 1 2 17 17 124/2 MANIKTALA STREET ALOK SANTRA SAMAR SANTRA 2 2 4 19 18 124/2 MANIKTALA STREET ALOKA SAHA NARAYAN CH. -

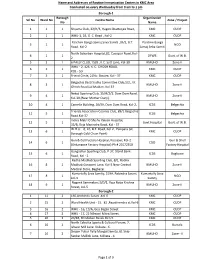

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

Annual Report 2018-19 the Purpose of Life Is Not to Be Happy

Annual Report 2018-19 The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it make some difference that you have lived and lived well. Ralph Waldo Emerson Photographs courtesy by: Jayati Saha, Saheli Das, Nilargha Chatterjee, Om Prakash Yadav and the staff of Iswar Sankalpa Annual Report 2018-19 SARBANI DAS ROY Dear friends, SECRETARY In the magical 12th year of its journey, I am happy to share the struggles and successes of the mind champions and Team Iswar Sankalpa through the difficult terrains of recovery-oriented programs of treatment, care and rehabilitation. The single most important thread running through all the pages of the year was the way in which we have broken the stony walls of social isolation and embraced our fellow citizens – doubly marginalised by homelessness and mental illness. For too long, have we looked away from this bundle of rags and dirt. For too long have we been afraid of her unpredictable behaviour. But it has taken this embrace to touch the pain in her and the human in me. The discovery of the deepest reservoirs of strength and ‘capacity’ of persons whom the world had held with increasing despair and the way in which we have succeeded in bringing delight to the care process have been ‘magical moments’ we have cherished over the year. Hope you will enjoy reading this testament of love and toil of a committed team of changemakers. CONTENT 08 12 16 Naya Daur: Outreach Sarbari and Urban Mental Health Programme Marudyan: Shelter Programme Programmes 20 23 24 -

Mandatory Details

Mandatory details 1 1. Name of the Institution: St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Kolkata 2. Course: B.Ed. (with an annual intake of 100 students). 3. Application Code: NA (Recognition number: NCTE [F. ERC/ NCTE/ (APE00026) /B.Ed. (Revised Order) /2015/31946 Date: 23/05/2015]). 4. Fully / Partially compliance as per prescribed ERC’s proforma: Annexure - I 5. Institution’s website: www.sxccal.edu 2 I. Student Details: Number of students course-wise; year-wise along with details: Annexure – I Number of students: 100, Course: B.Ed., Year: 2020 Sl. No. Sl. the of Name student admitted Name Father’s Address Category (Gen/SC/ST/OBC/ Others) Admission of Year Result Percentage fee Admission No., (Receipt Date Amount) & 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 PUTHENPURACKAL HOUSE, ELAPPUPARA P O, V- SSBI9185830688, KOTTAYAM, 04.09.20, STELLA SAJI 1. SAJI ROY PATHANAMTHITTA, GEN 2020 1ST 76.75 15,350 PIN- 689656 2. 29/18 TOLAFATAK MANASATALA, MAJHER 109951994278, PRANAB KUMAR SAYANTIKA MONDAL RASTA, P.O-CHINSURAH, SC 2020 54.50 04.09.20, MONDAL 2ND DIST-HOOGHLY, 15,350 PIN-712101, SANGHATINAGAR BALAGARH, WEST SUR29186893521, SREETI GEORGE GOOWIN GEORGE BANDEL, PO-SAHAGANJ, GEN 2020 1ST 66.75 04.09.20, BISWAS 3. DIST.-HOOGHLY, 15,350 PIN-712104 SHMP9187973440, AREEBA AKHTAR 46F, SHAMSUL HUDA GEN 2020 70.63 05.09.20, PARWEZ AKHTAR 1ST 4. ROAD, PIN- 700017 15,350 VIJAY KUMAR 109952425520, 17/4, HAT LANE, BLOCK – D, NIDHI MISHRA MISHRA GEN 2020 62.13 05.09.20, 5. FLAT NO. 116, 1ST HOWRAH- 711101 15,350 BF - 7/12/5 , SSBI9188522432, DESHBANDHU NAGAR, PARAMITA ROY PRAKASH ROY OBC 2020 2ND 54.63 05.09.20, 6. -

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

Arthik Lipi Kolkata

CYMK Ñ˛úÑ˛yì˛y, ÷e´ÓyÓ˚, 26 ã%ò 2020 KolkataFriday June 26, 2020 Arthik Lipi, Page 9 9 Óy!íムGovernment of West Bengal ˛ô)Ó≈ ˆÓ˚ˆÏúÓ˚ õyúÓy£# ˆúy!v˛Ç Irrigation & Waterways Directorate Office of the Sub-Divisional Officer Govt. of West Bengal 12.304 ›˛ˆÏò ›˛ˆÏò ˆ˛ôÔ§ˆÏäȈÏäÈ Canning Irrigation Sub-Division NIQ NO. - 02/KSHD OF 2020-2021 AFFIDAVIT Govt. of West Bengal Canning, South 24 Parganas Quotations are invited for Ñ˛úÑ˛yì˛yñ 25 ã%òÉ ˆÑ˛y!¶˛v˛ ÈÙÈ19 Á x!ö˛¢yÓ˚Ó˚y £yì˛ !õ!úˆÏÎ˚ˆÏäÈ– Sealed quotation is hereby I, RANJANA YADAV NOTICE INVITING TENDER “Emergent work for ≤Ãyî%¶≈˛yˆÏÓÓ˚ ˆÏ≤Ã!«˛ˆÏì˛ ˆîüÓƒy˛ô# ~£z ˆ›˛Ñ˛¢£z ≤ÃÎ˚yˆÏ¢Ó˚ ¢yˆÏÌ DAUGHTER OF SURESH invited by the A.E./Barasat NO. : 01 OF 2020-21 úÑ˛v˛yv˛zò ¢ˆÏ_¥Áñ ˛ô)Ó≈yM˛Èú ˛ô)Ó≈ÈÙȈÏÓ˚úÁˆÏÎ˚ 1.4.2020 ˆÌˆÏÑ˛ Electrical Sub-Division, sanitization & disinfection YADAV, AGED ABOUT 25 A Notice Inviting Tender No. 01 services at (i) O/O AE, PWD, Barasat, N-24 Pgs. for the ˆÓ˚úÁˆÏÎ˚ !Ó!¶˛ß¨ xM˛ÈˆÏú 24.06.2020 ˛ôÎ≈hs˛ 11.612 YEARS BY OCCUPATION Govt. of West Bengal of 2020-21 is invited SSKMHSD & SKHSD-I within work : ≤ÈÏÎ˚yãò#Î˚ ˛ôíƒ ~ÓÇ xòƒyòƒ !õ!úÎ˚ò ›˛ò õyúÓy£# ˆÓ˚!ãˆÏfl˛T…üò NOTICE INVITING QUOTATION (circulated vide Memo No.180 SSKM Hospital Compound, PRIVATE SERVICE NIQ No. 05/Q of 20-21 1/EE-II/LDCD of 2020-21 Dated 25-06-2020) by the due to outbreak of COVID-19. -

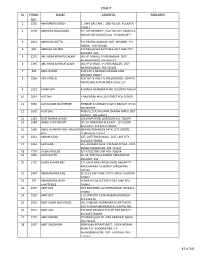

Sl Form No. Name Address Remarks

STARLIT SL FORM NAME ADDRESS REMARKS NO. 1 2235 ABHIMANYU SINGH 2, UMA DAS LANE , 2ND FLOOR , KOLKATA- 700013 2 1998 ABHISHEK MAJUMDER R.P. APPARTMENT , FLAT NO-303 PRAFULLA KANAN (W) KOLKATA-101 P.S-BAGUIATI 3 1922 ABHRANIL DUTTA P.O-PRAFULLANAGAR DIST-24PGS(N) , P.S- HABRA , PIN-743268 4 860 ABINASH HALDER 139 BELGACHIA EAST HB-6 SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA -106 5 2271 ABU HENA MONIRUL ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI, P.S-REJINAGAR DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 6 1395 ABU HENA SAHINUR ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI , P.S-REGINAGAR , DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 7 446 ABUL HASAN B 32 1AH 3 MIAJAN OSTAGAR LANE KOLKATA 700017 8 3286 ADA AFREEN FLAT NO 9I PINES IV GREENWOOD SONATA NEWTOWN ACTION AREA II KOL 157 9 1623 ADHIR GIRI 8 DURGA CHANDRA ROAD KOLKATA 700014 10 2807 AJIT DAS 6 RAJENDRA MULLICK STREET KOL-700007 11 3650 AJIT KUMAR MUKHERJEE SHIBBARI K,S ROAD P.O &P.S NAIHATI DT 24 PGS NORTH 12 1602 AJOY DAS PO&VILL SOUTH GARIA CHARAK MATH DIST 24 PGS S PIN 743613 13 1261 AJOY KUMAR GHOSH 326 JAWPUR RD. DUMDUM KOL-700074 14 1584 AKASH CHOUDHURY DD-19, NARAYANTALA EAST , 1ST FLOOR BAGUIATI , KOLKATA-700059 15 2460 AKHIL CHANDRA ROY MNJUSRI 68 RANI RASHMONI PATH CITY CENTRE ROY DURGAPUR 713216 16 2311 AKRAM AZAD 227, DUTTABAD ROAD, SALT LAKE CITY , KOLKATA-700064 17 1441 ALIP JANA VILL-KHAMAR CHAK P.O-NILKUNTHIA , DIST- PURBA MIDNAPORE PIN-721627 18 2797 ALISHA BEGUM 5/2 B DOCTOR LANE KOL-700014 19 1956 ALOK DUTTA AC-64, PRAFULLA KANAN KRISHNAPUR KOLKATA -101 20 1719 ALOKE KUMAR DEY 271 SASHI BABU ROAD SAHID NAGAR PO KANCHAPARA PS BIZPUR 24PGSN PIN 743145 21 3447 -

People Without History

People Without History Seabrook T02250 00 pre 1 24/12/2010 10:45 Seabrook T02250 00 pre 2 24/12/2010 10:45 People Without History India’s Muslim Ghettos Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui Seabrook T02250 00 pre 3 24/12/2010 10:45 First published 2011 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 www.plutobooks.com Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui 2011 The right of Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3114 0 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3113 3 Paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, 33 Livonia Road, Sidmouth, EX10 9JB, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the USA Seabrook T02250 00 pre 4 24/12/2010 10:45 Contents Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 1. -

167 – Maniktala Assembly Constituency Sl

167 – Maniktala Assembly Constituency Sl. Name & Address of the Polling Premises P.S. Attached Ward No Borough Police Station THE PARK INSTITUTION, 12, Mohanlal Street, P.S. 1 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 12 II Ultadanga Ultadanga, Kolkata-4 K.M.C.P.SCHOOL, 44, Canal West Road, P.S. 2 9, 10 12 II Ultadanga Ultadanga, Kolkata-4 J.B. ROY STATE AYURVEDIC MEDICAL 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 3 COLLEGE & HOSPITAL, 170-172, Raja Dinendra 12 II Ultadanga 16, 17 Street, Kol-4 ULTADANGA UNITED HIGHER SECONDARY 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 4 12 II Ultadanga SCHOOL, 49, Ultadanga Road, Kolkata -4 23, 24, 25 DASPARA ABAITANIK PRATHAMIK 5 VIDYALAYA, 10/2, Kritibas Mukherjee Road, Kolkata 26, 27 13 III Ultadanga - 67 CHAYANIKA VIDYAMANDIR, 7/1, Gorapada Sarkar 6 28, 29, 37, 38, 52 13 III Ultadanga Lane, Ultadanga, Kolkata - 67 SARADA PROSAD INSTITUTION FOR GIRLS, 1/1 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 7 13 III Ultadanga CIT Sch VIII M Dhar Bagan, (PS-Ultadanga) Kolkata - 9 60 SUDHIR PAL PRATHAMIK VIDYALAYA, 27, B. 8 35, 36 13 III Ultadanga Adhar Chandra Das Lane, Kolkata - 67 NEW ST THOMAS PUBLIC SCHOOL, 7/H, Gorapada 9 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 13 III Ultadanga Sarkar Lane, Ultadanga, Kolkata - 67 MUNICIPALITY WARD OFFICE, WARD NO. -13, 10 45, 46 13 III Maniktala 17, Bidhan Nagar Road, Kolkata-700067 SITALA SANGHA PRATHAMIK VIDYALAYA, 11 44, 51 13 III Ultadanga 20/H/7/2, Kirtibas Mukerjee Rd., Kolkata - 67. NATIONAL ACADEMY OF CUSTOM EXC & NAR 12 EST REGN. P-27 CIT Scheme VIIIM, Bidhan Nagar 47, 48, 57, 58, 59 13 III Maniktala Rd., Kolkata - 67. -

Schedule of DUARE SARKAR: Round-5 the KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION

Schedule of DUARE SARKAR: Round-5 THE KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Date Borough Ward Day Venue 27-01-2021 I 7 Wednesday Bagbazar Sarbajanin Durgotsab Math, 78 Baghbazar Street 28-01-2021 I 1 Thursday Uttarayan Community Hall, 1B, Gopal Chatterjee Road, kol - 02 29-01-2021 I 8 Friday A.V. School, 88 Shyambazar Street 02-02-2021 I 2 Tuesday Muktadhara Community Hall, 34 Harekrishna Sett Lane,Kol-50 03-02-2021 I 6 Wednesday Geetanjali community hall, 2 no. Lock Gate Road 05-02-2021 I 5 Friday Sonar Tori Community Hall, 7MG Tara Saankar Sarani 05-02-2021 I 9 Friday Pratistha Community Hall, 55 Jyotindra Mohan Avenue Manohar Academy School, Milk Colony, 64/77 Khidiram Bose Sarani, 06-02-2021 I 3 Saturday Duttabagan, kol - 37 08-02-2021 I 4 Monday Pubali Community Hall, Kheyali Park, Rani Harshamukhi Road 03-02-2021 II 15 Wednesday Pratyasa Community Hall, 82 Raja Dinendra Street, kol- 700006 03-02-2021 II 16 Wednesday GOA BAGAN WARD OFFICE 16 GOA BAGAN C.I.T PARK 04-02-2021 II 19 Thursday B. K. Pal Avenue Park, 105 B.K. Pal Avenue, Kol - 5 05-02-2021 II 10 Friday Laha Colony Math 05-02-2021 II 17 Friday Gana Bhawan, 22 Jatin Mohan Avenue, Sovabazar, Kol - 04 06-02-2021 II 18 Saturday Joy Mitra Park, 436 Rabindra Sarani, Kol-6 06-02-2021 II 20 Saturday Nahabat Community Hall 08-02-2021 II 11 Monday Star Community Hall, Khudiram Bose Lane, kol - 6 Monihar Community Hall, Raja Dinendra Street, near Deshbandhu Park, Kol- 08-02-2021 II 12 Monday 700006 28-01-2021 III 34 Thursday 27, Chaulpatti road, Kolkata- 10 29-01-2021 III 35 Friday Balir Math, 8 K G Bose Sarani, Kol - 85 01-02-2021 III 33 Monday Sarkar Math, 106 Beliaghata main road 03-02-2021 III 31 Wednesday Siksha Niketan School, 30E Ramkrishna Samadhi Road 04-02-2021 III 29 Thursday Community Hall, LIG Quarter, 19 No. -

BUS ROUTE-18-19 Updated Time.Xls LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS

LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT TO TO CONDITION OF THE ROAD CONDITION OF THE ROAD ROUTE NO - 1 ROUTE NO - 2 SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS 1 DUMDUM CENTRAL JAIL 13.00 1 IDEAL RESIDENCY 13.05 2 CLIVE HOUSE, MALL ROAD 13.03 2 KANKURGACHI MORE 13.07 3 KAJI PARA 13.05 3 MANICKTALA RAIL BRIDGE 13.08 4 MOTI JEEL 13.07 4 BAGMARI BAZAR 13.10 5 PRIVATE ROAD 13.09 5 MANICKTALA P.S. 13.12 6 CHATAKAL DUMDUM ROAD 13.11 6 MANICKTALA DINENDRA STREET XING 13.14 7 HANUMAN MANDIR 13.13 7 MANICKTALA BLOOD BANK 13.15 8 DUMDUM PHARI 01:15 8 GIRISH PARK METRO STATION 13.20 9 DUMDUM STATION 01:17 9 SOVABAZAR METRO STATION 13.23 10 7 TANK, DUMDUM RD 01:20 10 B.K.PAUL AVENUE 13.25 11 AHIRITALA SITALA MANDIR 13.27 12 JORABAGAN PARK 13.28 13 MALAPARA 13.30 14 GANESH TALKIES 13.32 15 RAM MANDIR 13.34 16 MAHAJATI SADAN 13.37 17 CENTRAL AVENUE RABINDRA BHARATI 13.38 18 M.G.ROAD - C.R.AVENUE XING 13.40 19 MOHD.ALI PARK 13.42 20 MEDICAL COLLEGE 13.44 21 BOWBAZAR XING 13.46 22 INDIAN AIRLINES 13.48 23 HIND CINEMA XING 13.50 24 LEE MEMORIAL SCHOOL - LENIN SR. 13.51 ROUTE NO - 3 ROUTE NO - 04 SL NO. -

Observer List

Up-to-date Details of Observers deployed in Kolkata (North) Electoral District in connection with General Election to West Bengal Legislative Assembly, 2016 Observer's Contact Details Liaison Officer's details Accomodation details Sl. Name of Deployed for Code Service Batch No. Observer which AC Mobile Mobile E-mail ID E-mail ID Designati Name Mobile No. Place Phone Fax (Official) (Personal) (Official) (Personal) on General Observer Sr. SOI, Coal India Guest (033) (033) Mr. Alok observerwbla16 awasthialok@g 01 G-13320 IAS 2002 162-Chowrangee 7044482403 09425551000 Sri Subrota Roy Civil 8902405833 House, 12, Lord Sinha 2287 2287 Awasthi [email protected] mail.com Defence Road, Kolkata 2220 2220 Caretaker Kolkata Port Trust (033) (033) Mr. Jannu observerwbla16 [email protected] Sri Kalyan Kumar 02 G-15184 IAS 2002 163-Entally 7044482406 09845133642 in-charge, 9831149160 Guest House, Annex 2223 2223 R.R [email protected] c.in Saha PWD Building, 1st Floor 0263 0263 Mr. Sr. SOI, Coal India Guest (033) (033) observerwbla16 7059245512 03 Hanumant IAS 2001 164-Beleghata 7044482405 09829011111 Sri Tapas Barua Civil House, 12, Lord Sinha 2287 2287 [email protected] 9433314439 Singh Bhati Defence Road, Kolkata 2220 2220 observerwbla16 Sr. SOI, Coal India Guest (033) (033) Dr. V. 165-Jorasanko dr.vshanmuga Sri Anjan Kumar 04 G-21037 IAS 2007 7044482408 09927699403 [email protected] Civil 9903034660 House, 12, Lord Sinha 2287 2287 Shanmugam 167- Maniktala [email protected] Das om Defence Road, Kolkata 2220 2220 Mr. 166-Shyampukur observerwbla16 HA, Coal India Guest (033) (033) 05 G-15889 Pandurang B.