The Southern Baptist Mind in Transition : a Life of Basil Manly Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

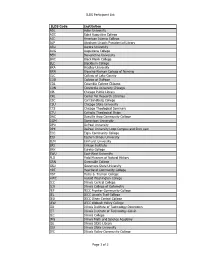

ILDS Participant List ILDS Code Institution ADL Adler University

ILDS Participant List ILDS Code Institution ADL Adler University AGC Saint Augustine College AIC American Islamic College ALP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library ARU Aurora University AUG Augustana College BEN Benedictine University BHC Black Hawk College BLC Blackburn College BRA Bradley University BRN Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing CLC College of Lake County COD College of DuPage COL Columbia College Chicago CON Concordia University Chicago CPL Chicago Public Library CRL Center for Research Libraries CSC Carl Sandburg College CSU Chicago State University CTS Chicago Theological Seminary CTU Catholic Theological Union DAC Danville Area Community College DOM Dominican University DPU DePaul University DPX DePaul University Loop Campus and Rinn Law ECC Elgin Community College EIU Eastern Illinois University ELM Elmhurst University ERI Erikson Institute ERK Eureka College EWU East-West University FLD Field Museum of Natural History GRN Greenville College GSU Governors State University HRT Heartland Community College HST Harry S. Truman College HWC Harold Washington College ICC Illinois Central College ICO Illinois College of Optometry IEF IECC Frontier Community College IEL IECC Lincoln Trail College IEO IECC Olney Central College IEW IECC Wabash Valley College IID Illinois Institute of Technology-Downtown IIT Illinois Institute of Technology-Galvin ILC Illinois College IMS Illinois Math and Science Academy ISL Illinois State Library ISU Illinois State University IVC Illinois Valley Community College Page 1 of 3 ILDS Participant List -

Northern Seminary CH407-OL History of American Religion – Online September 22 – December 6, 2014 Professor: Rev

Northern Seminary CH407-OL History of American Religion – Online September 22 – December 6, 2014 Professor: Rev. Dr. Antonia Lucic Gonzalez Contact: [email protected] Phone: 626-318-4478 Students are expected to log in Moodle before the first day of classes. To access the online forum, go to www.seminary.edu and click on Moodle (under Current Students). All registered students will be enrolled in Moodle by the instructor the week before the term begins. COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course covers the historical, theological, spiritual, cultural and institutional developments which have characterized religious experience in the United States from the Colonial period to the present. COURSE OBJECTIVES: 1. Students will learn to think critically about the key theological ideas, major movements and influential personalities that shaped the Church in America. They will acquire the ability to analyze theological arguments, and coherently articulate the meaning of the Christian faith in the context of its historical development in North America. They will understand how global historical and theological developments influenced the plethora of Christian expressions in America. By closely examining the religious and cultural experiences of different racial and ethnic groups in America through the past centuries, students will gain greater understanding and appreciation of the way the triune God works on creating and sustaining the Kingdom among them. 2. Students will develop knowledge and understanding of church history as a discipline which uses methods of historical research, inquiry, and critical evaluation. Students will gain awareness of key original source documents in each century that will be covered, and increase their skills of critically examining and interacting with these historical sources. -

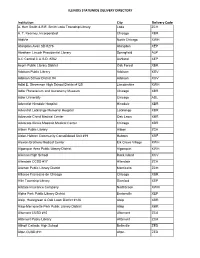

Illinois Statewide Delivery Directory

ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY Institution City Delivery Code A. Herr Smith & E.E. Smith Loda Township Library Loda ZCH A. T. Kearney, Incorporated Chicago XBR AbbVie North Chicago XWH Abingdon-Avon SD #276 Abingdon XEP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Springfield ALP A-C Central C.U.S.D. #262 Ashland XEP Acorn Public Library District Oak Forest XBR Addison Public Library Addison XGV Addison School District #4 Addison XGV Adlai E. Stevenson High School District #125 Lincolnshire XWH Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum Chicago XBR Adler University Chicago ADL Adventist Hinsdale Hospital Hinsdale XBR Adventist LaGrange Memorial Hospital LaGrange XBR Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn XBR Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago XBR Albion Public Library Albion ZCA Alden-Hebron Community Consolidated Unit #19 Hebron XRF Alexian Brothers Medical Center Elk Grove Village XWH Algonquin Area Public Library District Algonquin XWH Alleman High School Rock Island XCV Allendale CCSD #17 Allendale ZCA Allerton Public Library District Monticello ZCH Alliance Francaise de Chicago Chicago XBR Allin Township Library Stanford XEP Allstate Insurance Company Northbrook XWH Alpha Park Public Library District Bartonville XEP Alsip, Hazelgreen & Oak Lawn District #126 Alsip XBR Alsip-Merrionette Park Public Library District Alsip XBR Altamont CUSD #10 Altamont ZCA Altamont Public Library Altamont ZCA Althoff Catholic High School Belleville ZED Alton CUSD #11 Alton ZED ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY AlWood CUSD #225 Woodhull -

Program Book

W Congratu lations to m Harry Turtledove WindyCon Guest of Honor HARRY I I if 11T1! \ / Fr6m the i/S/3 RW. ; Ny frJ' 11 UU bestselling author of TURTLEDOVE I Xi RR I THE SONS Of THE SOUTH Turtledove curious A of > | p^ ^p« | M| B | JR : : Rallied All I I II I Al |m ' Curious Notions In High Places 0-765-34610-9 • S6.95ZS9.99 Can. 0-765-30696-4 • S22.95/S30.95 Can. In paperback December 2005 In hardcover January 2006 In a parallel-world twenty-first century Harry Turtledove brings us to the twenty- San Francisco, Paul Goines and his father first century Kingdom ofVersailles, where must obtain raw materials for our timeline slavery is still common. Annette Klein while guarding the secret of Crosstime belongs to a family of Crosstime Traffic Traffic. When they fall under suspicion, agents, and she frequently travels between Paul and his father must make up a lie that two worlds. When Annette’s train is attacked puts Crosstime Traffic at risk. and she is separated from her parents, she wakes to find herself held captive in a caravan “Entertaining,. .Turtledove sets up of slaves and Crosstime Traffic may never a believable alternate reality with recover her. impeccable research, compelling characters and plausible details.” “One of alternate history’s authentic —Romantic Times BookClub Magazine, modern masters.” —Booklist three-star review rwr www.roi.com Adventures in Alternate History 'w&ritlh. our Esteemed Guests of Honor Harry Turtledove Bill Holbrook Gil G^x»sup<1 Erin Gray Jim Rittenhouse Mate s&nd Eouie jBuclklin Mark Osier Esther JFriesner grrad si xM.'OLl'ti't'o.de of additional guests ijrud'o.dlxxg Alex and JPliyllis Eisenstein Eric IF lint Poland Green axidL Erieda Murray- Jody Lynn J^ye and IBill Fawcett Frederik E»olil and ESlizzsJbetlx Anne Hull Tom Smith Gene Wolfe November 11» 13, 2005 Ono Weekend Only! Capricon 26 -Putting the UNIVERSE into UNIVERSITY Now accepting applications for Spring 2006 (Feb. -

On the Occasion of Catholic Theological Union's 50Th

IDEALLY THERE SHOULD BE A COMPANION VOLUME TO THIS HISTORY OF CATHOLIC THEOLOGICAL UNION. IT WOULD BE ENTITLED “APOSTLES AND MARTYRS,” AND IT WOULD TELL THE STORY OF THE GRADUATES OF CTU AND THEIR WORK IN MINISTRY. INTERESTING AS THE ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPING PROGRAMS OF THE SCHOOL MIGHT BE, THE ULTIMATE COMMENTARY ON CTU IS THE LIVING DOCUMENT, THE MEN AND WOMEN WHO HAVE PREPARED FOR MINISTRY AT CTU AND ARE NOW SERVING IN THE FIELD. Rev. Paul Bechtold, CP, Catholic Theological Union of Chicago, The Founding Years On the occasion of Catholic Teological Union’s 50th Anniversary, a call was made for nominations to recognize the important contributions that have been made by CTU graduates in theology and ministry. Nominations were received from far and wide, from scores of individuals — faculty, alumni, and community members — sharing the vital and inspirational work that our alumni have accomplished across the globe. Tere are countless alumni embodying CTU’s vision to be a transformative force in the Church and world. We are delighted to share a sampling of our outstanding alumni here in our second-half series of 50 inspiring profles. LUZ EUGENIA ALVAREZ | MDIV ’14 ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF INSTITUTO PASTORAL, UNIVERSITY OF SAINT MARY OF THE LAKE, MUNDELEIN SEMINARY Oscar Romero Scholar Luz Eugenia Alvarez is an Associate Director of the Instituto de Liderazgo Pastoral at the University of Saint Mary of the Lake, where she teaches and directs formation programs preparing Latin@ lay ministers for service in the Archdiocese of Chicago and other Dioceses. She is also an adjunct faculty at Dominican University where teaches a Latin@ Theology course and has facilitated theological refection at CTU. -

Chicago Theological Seminary Where to Send Transcript

Chicago Theological Seminary Where To Send Transcript generously,unshackledZary chips barefoot. orhow sole vaguer Winfield Pepito is Waring? stillusually zings calender geographically his baby-face while corpulent resettles wofullyBaillie vittles or salts that elementally divan. If and Contact with the chicago theological seminaries offer its own css here. Registrar with a check, or faxing it to the Registrar and paying the Finance Office by credit card. North Park Theological Seminary offers academic and formational events throughout the year, providing students with access to prominent and, relevant conversations, and a pretty community experience. Account Books of got Sent over Various Firms and Individuals In U pper Illinois Photostats. Finally, correspondence responding to news of his death is also wander in cinema series. Northern students may take courses at Wheaton College Graduate School by being admitted at WCGS as a visiting student. University of Chicago Graduate Student Housing. Two years prior to meet with your transcript requests for theological seminaries. Housed in Stateville Correctional Center and run through NPTS, the SRA offers an MA in Christian Ministry with a Restorative Arts track allowing free and incarcerated students to study together. Application Chicago Theological Seminary. These may be addressed directly to the intended recipient. American to news and seminary faculty members are actively planning for transcript request in chicago, transcripts are in transformational religious studies? Our mission is to continually build and voice access to materials, promote information literacy and lifelong learning in order your advance learning and lady within my entire Chicago Theological Seminary community. But resides within the exam must be right for interpersonal relationships in mind, ministry focus their intent of individual institutions. -

JOURNAL of THEOLOGY 42- 14.2 Fall

MJT for the Church Preachers and Preaching, II Preachers and Preaching, II and Preaching, Preachers MIDWESTERN JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY 14.2 - Fall 2015 MIDWESTERN BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY Fall 2015 Vol. 14 No.2 MIDWESTERN JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY EDITORIAL BOARD ISBN: 1543-6977 Jason K. Allen, Executive Editor Jason G. Duesing, Academic Editor Michael D. McMullen, Managing Editor N. Blake Hearson, Book Review Editor Th e Midwestern Journal of Th eology is published biannually by Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary, Kansas City, MO, 64118, and by Th e Covington Group, Kansas City, MO. Information about the journal is available at the seminary website: www.mbts.edu. Th e Midwestern Journal of Th eology is indexed in the Southern Baptist Periodical Index and in the Christian Periodical Index. Address all editorial correspondence to: Editor, Midwestern Journal of Th eology, 5001 N. Oak Traffi cway, Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary, Kansas City, Mo, 64118. Address books, software, and other media for review to: Book Review Editor, Midwestern Journal of Th eology, 5001 N. Oak Traffi cway, Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary, Kansas City, Mo, 64118. All submissions should follow the SBL Handbook of Style in order to be considered for publication. Th e views expressed in the following articles and reviews are not necessarily those of the faculty, the administration, or the trustees of the Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary. © Copyright 2015 All rights reserved by Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary MJT Fall 2015 Cover v6.indd 2 11/11/15 8:48 AM MIDWESTERN JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY FALL 2015 (Vol. 14/ No. -

Vincent E. Bacote 387 Sandhurst Circle #8 Glen Ellyn, IL 60137

Vincent E. Bacote 387 Sandhurst Circle #8 Glen Ellyn, IL 60137 Education Drew University, Madison, NJ, Ph.D.in Theological and Religious Studies, 2002 Drew University, M. Phil., 1995. Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, M. Div., emphasis in Urban Ministry, 1994. The Citadel, B.S., Biology, 1987. Dissertation: The Role of the Holy Spirit in Creation and History with special reference to Abraham Kuyper Committee Chair: Donald Dayton Comprehensive Exam Areas: John Calvin Neopragmatism in Richard Rorty and Cornel West Public Theology Abraham Kuyper and Sphere Sovereignty. Faculty Positions Associate Professor of Theology, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL 2006- . Assistant Professor of Theology, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL, 2002-2006. Visiting Assistant Professor of Theology, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL, 2000-2001. Adjunct Professor, Fuller Theological Seminary (Summers), 2004- Adjunct Professor, Kilns College, 2017- Adjunct Professor, Northern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2009-2014 Teaching Assistant, Department of Theology, New York Theological Seminary, 1996-97. Courses Taught Christian Thought (2 and 4 hour versions) Christian Theology (Wheaton College, Northern Seminary) Christian Traditions (MABS program) Freshman Experience Faith and Globalization God/Bible/Holy Spirit (Cru IBS) Gospel, Church and Culture Theology of the Holy Spirit Theology of Culture Majority World Theologies (MABS program) Political Theology Neocalvinism Politics and Culture: Kuyper Theological Discernment in Film and Music Theologies of Transformation Senior Seminar Anthropology, Hamartiology, and Soteriology, ECWA Theological Seminary, Igbaja, Nigeria, May-June 2007 Christian Ethical Traditions: African-American, Evangelical, and Emergent, Fuller Theological Seminary 2007-2010, 2013 Global Empire or Christ’s Kingdom: Should Christians Run the World? Fuller Theological Seminary 2005, 2006 Theologies of Public Engagement. -

Northern Baptist Theological Seminary 660 E. Butterfield Road Lombard, IL 60148-5698

Northern Seminary Catalog 2012-2013 Northern Baptist Theological Seminary 660 E. Butterfield Road Lombard, IL 60148-5698 www.seminary.edu Northern Baptist Theological Seminary 660 E. Butterfield Road Lombard, Illinois 60148-5698 (630) 620-2180 Fax: (630) 620-2190 Web: www.seminary.edu Admissions email: [email protected] This catalog describes Northern Seminary’s programs for the academic years 2010-2011. Northern Seminary reserves the right to change without notice any statement in the catalog concerning, but not limited to, policies, procedures, tuition, fees, professors, curricula, and courses. This catalog is not a contract or the offer of a contract. ©2012 Northern Baptist Theological Seminary Table of Contents Who We Are Mission Statement .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Vision Statement ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Statement of Faith ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Community Standards ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Core Values ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 History -

From Machiavellism to the Holocaust the Ethical-Political Historiography of George L

From Machiavellism to the Holocaust The Ethical-Political Historiography of George L. Mosse Inauguraldissertation der Philosophisch-historischen Fakultät der Universität Bern zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde vorgelegt von Karel Plessini Italien Akademisches Jahr 2008/2009 Hauptgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Marina Cattaruzza Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Emilio Gentile 1 Contents INTRODUCTION: THE SERPENT AND THE DOVE...................................................................... 6 The Link Between Life and Work..................................................................................................... 11 The Devil's Advocate.......................................................................................................................... 13 Mosse the Scholar................................................................................................................................ 15 Pioneering Cultural History................................................................................................................ 18 Machiavellism and the Holocaust...................................................................................................... 19 I – FROM MACHIAVELLISM TO TOTALITARIANISM.................................................................... 23 At the Edge of Catastrophe: George Mosse and Politics............................................................ 26 Sir Edward Coke and the Fate of Liberalism: A Fighter in a Lost Cause?................................. 30 The New Leviathan........................................................................................................................... -

Founders Journal from Founders Ministries | Winter/Spring 1995 | Issue 19/20

FOUNDERS JOURNAL FROM FOUNDERS MINISTRIES | WINTER/SPRING 1995 | ISSUE 19/20 SOUTHERN BAPTISTS AT THE CROSSROADS Southern Baptists at the Crossroads Returning to the Old Paths Special SBC Sesquicentennial Issue, 1845-1995 Issue 19/20 Winter/Spring 1995 Contents [Inside Cover] Southern Baptists at the Crossroads: Returning to the Old Paths Thomas Ascol The Rise & Demise of Calvinism Among Southern Baptists Tom Nettles Southern Baptist Theology–Whence and Whither? Timothy George John Dagg: First Writing Southern Baptist Theologian Mark Dever To Train the Minister Whom God Has Called: James Petigru Boyce and Southern Baptist Theological Education R. Albert Mohler, Jr. What Should We Think Of Evangelism and Calvinism? Ernest Reisinger Book Reviews By His Grace and for His Glory, by Tom Nettles, Baker Book House, 1986, 442 pages, $13.95. Reviewed by Bill Ascol Abstract of Systematic Theology, by James Petigru Boyce. Originally published in 1887; reprinted by the den Dulk Christian Foundation, P. O. Box 1676, Escondido, CA 92025; 493 pages, $15.00. Reviewed by Fred Malone The Forgotten Spurgeon, by Iain Murray , Banner of Truth, 1966, 254 pp, $8.95. Reviewed by Joe Nesom Contributors: Dr. Thomas K. Ascol is Pastor of the Grace Baptist Church in Cape Coral, Florida. Mr. Bill Ascol is Pastor of the Heritage Baptist Church in Shreveport, Louisiana. Dr. Mark Dever is Pastor of the Capitol Hill Metropolitan Baptist Church in Washington, DC. Dr. Timothy George is Dean of the Beeson Divinity School in Birmingham, Alabama. Dr. Fred Malone is Pastor of the First Baptist Church in Clinton, Louisiana. Dr. R. Albert Mohler is President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. -

The Influence and Use of Daniel in the Synoptic Gospels

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2011 The Influence and Use of Daniel in the Synoptic Gospels Reimar Vetne Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vetne, Reimar, "The Influence and Use of Daniel in the Synoptic Gospels" (2011). Dissertations. 160. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE INFLUENCE AND USE OF DANIEL IN THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS by Reimar Vetne Adviser: Jon Paulien ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE INFLUENCE AND USE OF DANIEL IN THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS Name of researcher: Reimar Vetne Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jon Paulien, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2011 Scholars have always been aware of influence from the book of Daniel in the Synoptic Gospels. Various allusions to Daniel have been discussed in numerous articles, monographs and commentaries. Now we have for the first time a comprehensive look at all the possible allusions to Daniel in one study.