Presidential Election of 2015 a Reading from the Uva Province Election 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 62.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, March 25, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 62 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. Sisira Jayakody, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Promotion, Rural and Ayurvedic Hospitals Development and Community Health Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament for 11.09.2020

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 8.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Friday, September 11, 2020 at 10.30 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Rajapaksa, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Douglas Devananda, Minister of Fisheries Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of Internal Security, Home Affairs and Disaster Management Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Health Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 8 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 73.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, May 04, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Rajapaksa, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing Hon. Rohitha Abegunawardhana, Minister of Ports & Shipping Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Douglas Devananda, Minister of Fisheries Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. (Prof.) G. L. Peiris, Minister of Education Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. Keheliya Rambukwella, Minister of Mass Media Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Namal Rajapaksa, Minister of Youth & Sports Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Health Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice ( 2 ) M. No. 73 Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection Hon. -

Sri Lanka Country Information Report No. 3

SRI LANKA COUNTRY INFORMATION REPORT NO. 3 15 June 2021 Combined Refugee Action Group, Geelong, Victoria For further information, contact: [email protected] The Combined Refugee Action Group is a network group that brings together people from a variety of backgrounds across the Geelong region in Victoria, (Refugee Support Groups, Church and Community Groups, Unions, Political Groups, Social Justice and Social Action Groups, students, and individuals). We are united by the shared aim of advocating for just, humane, and welcoming policies towards refugees and people seeking asylum. Table of Contents Purpose .................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 Legislative changes for greater control ...................................................................... 4 Rajapaksa family ................................................................................................................. 5 Attacks on journalists and human rights organisations ....................................... 6 Forced disappearances .................................................................................................... 9 The situation for Tamils ................................................................................................ 12 Election violence ............................................................................................................. -

Preferential Votes

DN page 6 SATURDAY, AUGUST 8, 2020 GENERAL ELECTION PREFERENTIAL VOTES Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Duminda Dissanayake 75,535 COLOMBO DISTRICT H. Nandasena 53,618 Rohini Kumari Kavirathna 27,587 K.P.S Kumarasiri 49,030 Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Rajitha Aluvihare 27,171 Wasantha Aluwihare 25,989 Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Dhaya Nandasiri 17,216 Ibrahim Mohammed Shifnas 13,518 Ishaq Rahman 49,290 Sarath Weerasekara Thissa Bandara Herath 9,224 Rohana Bandara Wijesundara 39,520 328,092 Maithiri Dosan 5,856 Suppaiya Yogaraj 4,900 Wimal Weerawansa 267, 084 DIGAMADULLA DISTRICT Udaya Gammanpila 136, 331 Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe 120, 626 PUTTALAM DISTRICT Bandula Gunawardena 101, 644 Pradeep Undugoda 91, 958 Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Wimalaweera Dissanayake 63,594 Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Sanath Nishantha Perera Sajith Premadasa 305, 744 80,082 S.M. Marikkar 96,916 D. Weerasinghe 56,006 Mujibur Rahman 87, 589 Thilak Rajapaksha 54,203 Harsha de Silva 82, 845 Piyankara Jayaratne 74,425 Patali Champika Ranawaka 65, 574 Arundika Fernando 70,892 Mano Ganesan 62, 091 Chinthaka Amal Mayadunne 46,058 Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Ashoka Priyantha 41,612 Mohomed Haris 36,850 Mohomed Faizal 29,423 BADULLA DISTRICT Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Hector Appuhamy 34,127 National Congress (NC) Niroshan Perera 31,636 Athaulla Ahamed 35,697 Nimal Siripala de Silva Muslim National Alliance (MNA) All Ceylon Makkal Congress (ACMC) 141, 901 Abdul Ali Sabry 33,509 Mohomed Mushraf -

Slpp Victory Drowning in Losses Due to Delay

NEW CHAPTER DELAY IN ECT TERMINAL PLANNING OPENS WITH GOVT. SLPP VICTORY DROWNING IN LOSSES DUE TO DELAY RS. 70.00 PAGES 64 / SECTIONS 6 VOL. 02 – NO. 46 SUNDAY, AUGUST 9, 2020 NO HAPPY NO MAJOR HOURS AT THE PAYPAL SPORTS BAR PROGRESS »SEE PAGES 8 & 9 »SEE PAGE 2 »SEE BUSINESS PAGE 1 »SEE PAGE 5 For verified information on the GENERAL PREVENTIVE GUIDELINES COVID-19 LOCAL CASES COVID-19 CASES coronavirus (Covid-19) contact any of the IN THE WORLD following authorities ACTIVE CASES TOTAL CASES 1999 TOTAL CASES Health Promotion Bureau 2,839 Suwasariya Quarantine Unit 0112 112 705 19,308,441 Ambulance Service Epidemiology Unit 0112 695 112 DEATHS RECOVERED Govt. coronavirus hotline 0113071073 Wash hands with soap Wear a commercially Maintain a minimum Use gloves when shopping, Use traditional Sri Lankan Always wear a mask, avoid DEATHS RECOVERD 1990 for 40-60 seconds, or rub available mask/cloth mask distance of 1 metre using public transport, etc. greeting at all times crowded vehicles, maintain PRESIDENTIAL SPECIAL TASK FORCE FOR ESSENTIAL SERVICES hands with alcohol-based or a surgical mask if showing from others, especially in and discard into a lidded instead of handshaking, distance, and wash hands 11 2,541 718,592 12,397,744 Telephone 0114354854, 0114733600 Fax 0112333066, 0114354882 handrub for 20-30 seconds respiratory symptoms public places bin lined with a bag hugging, and/or kissing before and after travelling 287 Hotline 0113456200-4 Email [email protected] THE ABOVE STATISTICS ARE CONFIRMED UP UNTIL 8.00 P.M. ON 07 AUGUST 2020 RanilBY OUR POLITICAL COLUMNIST A togroup of party seniors met at remainthe on the new leader, Wickremesinghe will Wijewardene, and Sagala Ratnayaka. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 59.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, March 10, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Rajapaksa, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. (Prof.) G. L. Peiris, Minister of Education Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. Keheliya Rambukwella, Minister of Mass Media Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Health Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation ( 2 ) M. No. 59 Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. -

(Since 1917), and Later Still Battenberg

THE 23RD COMMONWEALTH TOURNÉE WILL TAKE PLACE IN COLOMBO, SRI LANKA ON 15-17 NOVEMBER 2013 by Dr George Venturini * Cast of characters: Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Hanover-Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, later Windsor (since 1917), and later still Battenberg (since 1947) in the part of Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God Queen of the United Kingdom and Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth. In that capacity she officiated in Perth, Western Australia on 28 and 29 October 2011 for the 22nd Tournée. Elizabeth II is also Queen of Australia, of former Dominions such as Canada, New Zealand, as well as villes du plaisir et de débauche for the privileged such as Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, and fortunate places such as Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu, in each of which she is represented by a Governor-General. Elizabeth II holds a variety of other positions, among them Supreme Governor of the Church of England, Duke of Normandy, Lord of Mann, and Paramount Chief of Fiji. Her Majesty is also styled Duke of Lancaster, Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces of many of her realms, Lord Admiral of the United Kingdom, Defender of the Faith in various realms for differing reasons. Neither Elizabeth II nor her husband (and second cousin once removed as well as third cousin - and that may go a long way in explaining Prince Charles and much of the other progeny), Philip Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg known as Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, will take part in the Tournée, as they had done in Australia in 2011 at the declared cost - according to the Australian government - of AU$ 58 million. -

Minutes of Parliament for 23.02.2021

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 55.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, February 23, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Douglas Devananda, Minister of Fisheries Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Namal Rajapaksa, Minister of Youth & Sports Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms ( 2 ) M. No. 55 Hon. Siripala Gamalath, State Minister of Canals and Common Infrastructure Development in Settlements in Mahaweli Zones Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. -

A PROMISE to DELIVER Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure, Is One of the Young Cabinet Ministers of the Current Government

A PROMISE TO DELIVER Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure, is one of the young Cabinet Ministers of the current Government. He started the winning wave for the United National Party, with the Uva Provincial Elections that many do not remember today. The Minister speaks about the need to deliver on the promises made as every politician’s duty to his electorate. Many plans have been made to develop Badulla and the Uva Province. The sectors of telecommunication and digital infrastructure too are going through a massive change. There are extensive plans being formulated but delivery is the key. By Udeshi Amarasinghe Photography Menaka Aravinda and Mahesh Bandara Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure 2 BUSINESS TODAY SEPTEMBER 2016 businesstoday.lk businesstoday.lk SEPTEMBER 2016 BUSINESS TODAY 3 Who is Harin Fernando? Why did you join the UNP at that time? I was the vocal person of the group and I Harin Fernando is a citizen of Sri Lanka, a I am not from a political family and we had to contest against a Rajapaksa. That was politician and father of two children. Born in were not UNP or SLFP. But I always supported the biggest challenge. This was not in Colombo Wattala and representing the people of Badulla. the UNP. I was probably about three years either, which would have been easier. It was Currently holding a post of a ministry that is old and we were living in Ratmalana at that very difficult to get the campaign off the trying to create a digital revolution in Sri time. -

Loan Halt Creates Further Delay

DISPLACED BY LONG-TERM Govt. sets agenda: DEVELOPMENT THE LONG 20A gets priority WAIT CONTINUES RS. 70.00 PAGES 64 / SECTIONS 6 VOL. 02 – NO. 47 SUNDAY, AUGUST 16, 2020 TNA RECEDES IMF SUPPORT ONLY POLITICAL IF UNCONDITIONAL LEADERSHIP – GOVERNOR »SEE PAGE 6 »SEE PAGE 7 »SEE BUSINESS PAGE 1 »SEE PAGES 8 & 9 For verified information on the GENERAL PREVENTIVE GUIDELINES COVID-19 LOCAL CASES COVID-19 CASES coronavirus (Covid-19) contact any of the IN THE WORLD following authorities ACTIVE CASES TOTAL CASES 1999 TOTAL CASES Health Promotion Bureau 2,886 Suwasariya Quarantine Unit 0112 112 705 21,154,001 Ambulance Service Epidemiology Unit 0112 695 112 DEATHS RECOVERED Govt. coronavirus hotline 0113071073 Wash hands with soap Wear a commercially Maintain a minimum Use gloves when shopping, Use traditional Sri Lankan Always wear a mask, avoid DEATHS RECOVERD 1990 for 40-60 seconds, or rub available mask/cloth mask distance of 1 metre using public transport, etc. greeting at all times crowded vehicles, maintain 2,658 PRESIDENTIAL SPECIAL TASK FORCE FOR ESSENTIAL SERVICES hands with alcohol-based or a surgical mask if showing from others, especially in and discard into a lidded instead of handshaking, distance, and wash hands 11 758,942 13,980,941 Telephone 0114354854, 0114733600 Fax 0112333066, 0114354882 handrub for 20-30 seconds respiratory symptoms public places bin lined with a bag hugging, and/or kissing before and after travelling 217 Hotline 0113456200-4 Email [email protected] THE ABOVE STATISTICS ARE CONFIRMED UP UNTIL 6.00 P.M. ON 14 AUGUST 2020 No UNP in the House BY OUR POLITICAL EDITOR z National List slot vacant z Working Committee undecided The United National Party (UNP) has decided to seek The decision to seek more time to Sunday Morning that the party would possible to not name the National List ended on Friday (14). -

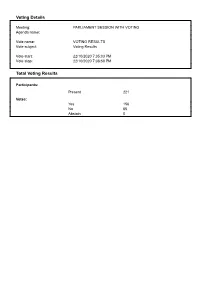

Voting Details Total Voting Results

Voting Details Meeting: PARLIAMENT SESSION WITH VOTING Agenda name: Vote name: VOTING RESULTS Vote subject: Voting Results Vote start: 22/10/2020 7:35:03 PM Vote stop: 22/10/2020 7:38:50 PM Total Voting Results Participants: Present 221 Votes: Yes 156 No 65 Abstain 0 Individual Voting Results OPPOSITION SIDE O 002. Rajitha Senaratne No O 003. Imitiaz Bakeer Marker No O 004. Tissa Attanayake No O 005. Rauff Hakeem No O 006. Gayantha Karunatileka No O 007. Lakshman Kiriella No O 008. Sajith Premadasa No O 009. Kumara Welgama No O 010. Patali Champika Ranawaka No O 011. Palany Thigambaram No O 013. Rajavarothiam Sampanthan No O 014. A. Adaikkalanthan No O 015. Anura Dissanayake No O 017. G.G. Ponnambalam No O 018. A.A.S.M. Raheem Yes O 019. C.V. Vickneshwaran No O 021. Kabir Hashim No O 022. Thalatha Atukorala No O 023. Abdul Haleem No O 024. Harin Fernando No O 025. Sarath Fonseka No O 026. Harsha De Silva No O 028. R.M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara No O 029. Dilip Wedaarachchi No O 030. Niroshan Perera No O 031. Eran Wickramarathne No O 032. J.C. Alawathuwala No O 033. Govinthan Karunakaram No O 034. Dharmalingam Sithadthan No O 035. Vijitha Herath No O 036. Harini Amarasuriya No O 037. Selvarasa Gajenthiran No O 038. S. Noharathalingam No O 039. S. Shritharan No O 040. M.A. Sumanthiran No O 041. Vadivel Suresh No O 042. Faizal Cassim Yes O 043. Ranjan Ramanayake No O 044. Ashok Abeysinghe No O 045.