Organising in Financial Call Centres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tender Document for Selection Call Centre Agency for Providing Centralized Candidate Services to the Unemployed Youth

1 NOTICE INVITING TENDER FOR Selection of a Call Centre Agency for providing Centralized Candidate Services to the Unemployed Youth of Haryana State No. RFP/Call Centre/2020-21/03 Panchkula, Dated 23/06/2020 The Government of Haryana through its Department i.e., Department of Employment (DoE) invites e-Tender for “Selection of a Call Centre Agency for providing Centralized Candidate Services to the Unemployed Youth of Haryana State” as detailed in the Scope of Work in this Tender document. The document can be downloaded from the website https://etenders.hry.nic.in and https://hreyahs.gov.in. Response to this Tender shall be deemed to have been done after careful study and examination of this document with full understanding of its implications. This section provides general information about the Issuer, important dates and addresses and the overall eligibility criteria for the parties. Issuer: Director General, Department of Employment, Bays No. 55-58, Paryatan Bhawan, Sector-2, Panchkula (Haryana)- 134151 E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://hreyahs.gov.in Phone No.- 0172-2570065 2 DISCLAIMER The information contained in the Request for Proposal (RFP) document or subsequently provided to Bidders, whether verbally or in documentary or any other form by or on behalf of the Department of Employment (hereafter referred as ‘DoE’), Government of Haryana, is provided to Bidders on the terms and conditions set out in the RFP and such other terms and conditions subject to which such information is provided. The RFP is not an agreement and is neither an offer nor invitation by the DoE to the prospective Bidder(s) or any other person. -

Transparency: a New Revenue Opportunity for Call Centres

Transparency: A New Revenue Opportunity for Call Centres February 2016 ServeMeBest, Suite No. 605, 6th floor (Part 4, Municipality 65) Manama Centre Building No. 104, Government Road, Area No. 316, Manama Centre, Kingdom of Bahrain. Transparency: A New Revenue Opportunity for Call Centres Summary For call centres, increased transparency in Customer Service can be a threat or an opportunity. ServeMeBest technology, backed by the world’s first Customer Service Transparency Standard, lets the best performers show the highest standards in respect, trust and openness in telephone care – and gain a new revenue stream. When a call centre embarks on a transparency strategy, it sends a powerful message to corporate clients: We are committed to maintaining our reputation, and the reputation of our clients. In addition, transparency is a statement of trust and confidence in staff and callers. A practical way to show transparency is the sharing of call recordings, so that callers are given the option to avail of their own copy of a recording. This not only sends a highly positive marketing message, but acts to ensure that telephone care standards are kept high: no long hold times, no getting passed around, no false promises or incorrect information. By implementing a transparency toolset and getting CSTS certification, call centres not only gain competitive position – they also get a new service to sell to clients. ServeMeBest provides that toolset. Trust+ is the world’s first call recording platform designed specifically for recording sharing. Survey+ is a mobile survey tool that enables short surveys to be dispatched by SMS immediately after a customer call. -

Government of India Request for Proposal (E-Tender) for Providing Kisan Call Centres Services Reference: „RFP / KCC / DAC&A

Government of India Ministry of Agriculture& Farmer Welfare, Department of Agriculture & Cooperation& Farmers Welfare, Request for Proposal (e-Tender) For providing Kisan Call Centres Services Reference: „RFP / KCC / DAC&FW / FEBRUARY, 2018‟ TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE No Disclaimer 3 Tender Notice 4 5-8 Instructions for Online Bid Submission Definitions 9-10 Project Description and Scope of Work 11-32 Instructions to Bidders 33-51 General Conditions for Bidding 52-61 Fundamental Requirements 62-67 Forms and Schedules 68-81 Annexures 82-93 Government of India Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare (Department of Agriculture, Cooperation & Farmers Welfare) DISCLAIMER The information contained in the Request for Proposal (RFP) document or subsequently, whether verbally or in documentary or any other form, by or on behalf of the Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare (MoA & FW), Department of Agriculture, Cooperation & Farmers Welfare (DAC&FW) is provided to Applicants (Bidders/tenderers) on the terms and conditions set out in the RFP and such other terms and conditions subject to which such information is provided. The RFP is not an agreement and is neither an offer nor invitation by the Department of Agriculture, Cooperation & Farmers Welfare (DAC&FW) to the prospective applicants or any other person. The purpose of this RFP is to provide interested parties with information that may be useful to them in the formulation of their Proposals pursuant to this RFP. Information provided in this RFP to the Applicants is on a wide range of matters, some of which depend upon the interpretation of law. The information given is not an exhaustive account of statutory requirements and should not be regarded as a complete or authoritative statement of law. -

Call Centre Work – Characteristics, Physical, and Psychosocial Exposure, and Health Related Outcomes

nr 2005:11 Call centre work – characteristics, physical, and psychosocial exposure, and health related outcomes Kerstin Norman Doctoral Thesis No. 2005-975 issn-0345-7524 Graduate School for Human-Machine Interaction Division of Industrial Ergonomics Department of Mechanical Engineering Linköping University National Institute for Working Life Department of Work and Health arbete och hälsa | vetenskaplig skriftserie isbn 91-7045-764-6 issn 0346-7821 National Institute for Working Life Arbete och Hälsa Arbete och Hälsa (Work and Health) is a scientific report series published by the National Institute for Working Life. The series presents research by the Institute’s own researchers as well as by others, both within and outside of Sweden. The series publishes scientific original works, disser tations, criteria documents and literature surveys. Arbete och Hälsa has a broad target group and welcomes articles in different areas. The language is most often English, but also Swedish manuscripts are wel come. Summaries in Swedish and English as well as the complete original text are available at www.arbetslivsinstitutet.se/ as from 1997. ARBETE OCH HÄLSA Editor-in-chief: Staffan Marklund Co-editors: Marita Christmansson, Birgitta Meding, Bo Melin and Ewa Wigaeus Tornqvist © National Institut for Working Life & authors 2005 National Institute for Working Life S-113 91 Stockholm Sweden ISBN 91–7045–764–6 ISSN 0346–7821 http://www.arbetslivsinstitutet.se/ Printed at Elanders Gotab, Stockholm Original papers This thesis is based on the following five publications, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals: I. Norman K, Nilsson T, Hagberg M, Wigaeus Tornqvist E, Toomingas A. -

Bpo Tender 17-18

Delhi Regional Office, F-8-11, Jhandewallan Flatted Factory Complex, Rani Jhansi Road, NEW DELHI – 110055. CIN: L51909DL1963GOI004033 No. MMTC/PMD/2017-18/RFP/BPO 14th July, 2017 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) MMTC invites e-tender ( techno-commercial) from BPO/CALL CENTRE COMPANIES to assist MMTC in sale of its Indian Gold Coin, Jewellery (Plain Gold/Studded), Sanchi Silverware and Gold/Silver Medallions Through its TOLL FREE NO 1800-1800-000. Delhi Regional Office, F-8-11, Jhandewallan Flatted Factory Complex, Rani Jhansi Road, NEW DELHI – 110055. CIN: L51909DL1963GOI004033 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS DETAILS PAGE NO. BACKGROUND, BID PROCESS, ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA ETC. CHAPTER 1 3-6 SCOPE OF WORK CHAPTER 2 7 INSTRUCTION & GENERAL TERMS & CONDITIONS TO BIDDERS CHAPTER 3 8-14 FORM A-1 15 FORM A-2 TECHNICAL BID DOCUMENTS 16 FORM A-3 17 FORM A-4 18 FORM A-5 19-20 FORM B COMMERCIAL BID DOCUMENTS 21 ANNEXURE I PERFORMANCE BANK GUARANTEE 22-23 NON – DISCLOSURE AGREEMENT ANNEXURE II 24-35 Delhi Regional Office, F-8-11, Jhandewallan Flatted Factory Complex, Rani Jhansi Road, NEW DELHI – 110055. CIN: L51909DL1963GOI004033 CHAPTER– 1 1.1 BACKGROUND MMTC was established in 1963, and is today India's leading international trading company. It is the first international trading company of India to be given the coveted status "SUPER STAR TRADING HOUSE" and it is the first Public Sector Enterprise to be accorded the status of "GOLDEN SUPER STAR TRADING HOUSE" for long standing contribution to exports. MMTC is the largest non-oil importer in India. MMTC's diverse trade activities encompass Third Country Trade, Joint Ventures, Link Deals - all modern day tools of international trading. -

Call Centre Officer

POSITION DESCRIPTION –Customer Service Officer POSITION TITLE: Customer Service Officer DEPARTMENT: Call Centre LOCATION: NSW ISSUED: January 2014 REPORTS TO: Call Centre Team Leader FUNCTIONAL Receives Guidance From: RELATIONSHIPS WITH: • National Customer Care Team Leader • Distribution Centre Managers DIRECT REPORTS Nil INCLUDE: SIGNIFICANT CONTACT • Distribution Centre Managers/Supervisors WITH: • Accounts Receivable Officers (Credit Controllers) • Sales Staff • Service Staff POSITION OVERVIEW The primary role of the Call Centre Officer is to receive inbound telephone calls in relation to customer services (placing orders, product inquiries, quotes, return, and problem solving) The role includes maintaining; completing and ensuring relevant documents are accurate and kept up to date in addition to supporting the Call Centre Telesales Team (outbound calls) when required in relation to specific sales /marketing activities. JOB SPECIFICATION • Receive and handle inbound telephone calls from dental customers and/or HSH Team and/or POC Team calling to place orders, inquire about products, return merchandise, obtain quotes and assist with all customer satisfaction related inquires, suggest related products (cross-selling) or upgrade products (up-selling) to the customer to purchase as well as recommending alternative clinical or other products to substitute when preferred product is unavailable. • When required support with telesales (outbound calls) to customers in relation to specific sales/marketing promotional campaigns. • Complete relevant documentation as required. maintain an accurate record keeping system (manually and electronically), prepare data, reports and documents , analyse information as required • Maintain effective and efficient work processes and procedures complying with Sox and ISO requirements • Remain aware and knowledgeable of promotional programs, competitive products, and merchandising- marketing practices. -

How Fortune 500 Companies Manage Their Contact Centers

How Fortune 500 Companies Manage Their Contact Centers www.tenfold.com Contents 2. Introduction 3. How Fortune 500 Companies Manage Their Call Centers 4. Availability and Providing Prompt Responses across Platforms 7. Embracing Social Media Connections 8. Consolidated Contact Center Operations 9. Captive Call Centers 1O. Outsourcing 12. Outsourcing to Different Countries 13. Do they have Directors for Each Call Center? What is the Leadership Structure? 15. Conclusion Matt Goldman Content Marketing Manager @growtenfold www.tenfold.com Contributors Colin Taylor CEO & Chief Chaos Officer, Taylor Reach Group, Inc. Nate Brown Director of Customer Experience, UL EHS Sustainability Blake Morgan Customer Experience Futurist, Keynote Speaker, Author of More Is More www.tenfold.com 1 Introduction Fortune 500 companies know that good customer service is a cornerstone of a suc- cessful business, and their customer-focused strategies prove it. Smaller businesses may have the advantage of the personal touch. On the other hand, the most suc- cessful big businesses give customers what they need when they need it with highly trained, dedicated customer service staff providing 24/7 assistance. No matter the size of your business, good customer service needs be at the heart of your business model if you wish to be successful. It is important to provide good cus- tomer service; to all types of customers, including potential, new and existing cus- tomers. Customer service is also important to an organization because it can help differentiate a company from its competitors. here are two types of companies that consistently make it to the top. One excels at conducting very basic customer interactions, day-in, day-out. -

Delivering the Digital Contact Centre

To start a new section, hold down the apple+shift keys and click to release this object and type the section title in the box below. Delivering the Digital Contact Centre Developed for the Deloitte Customer Service Leaders Forum Digital channels open new opportunities for contact centres Delivering the Digital Contact Centre A To start a new section, hold down the apple+shift keys and click to release this object and type the section title in the box below. Contents Foreword 1 Introduction: A place for the traditional contact centre 2 Delivering the digital experience 5 Owning and facilitating the omni-channel experience 7 Exploiting omni-channel information 9 A new breed of contact centre advisor 12 Conclusion 15 To start a new section, hold down the apple+shift keys and click to release this object and type the section title in the box below. Foreword With digital channel uptake steadily increasing, a new and increasingly valuable role is emerging for contact centres. In our previous paper*, we talked about how We believe that the advisor of the future will no longer *This paper is part of a organisations should adapt to embrace digital channels. be a process expert who ‘turns the wheel’ and makes series created for the Deloitte Customer Service This focussed on building digital services that can be the organisation work, but will instead move to being Leaders Forum. The previous accessed from any device and are intuitive to use, then an expert communicator, capable of delivering insight paper was “Customer marketing them effectively to customers at registration rather than information and adding substantive value Service in the Digital Age”. -

Establishment of Integrated 104 Centralized Call Center Cum Health Desk in Jammu and Kashmir on Build

MISSION DIRECTOR, NATIONAL HEALTH MISSION, J&K Jammu Office: Regional Institute of Health & Family Welfare, Nagrota, Jammu - 181221 Fax: 0191-2674114; Telephone: 2674244; e-mail: [email protected] Kashmir Office: Block ‘A’, Ground Floor, Old Secretariat, Srinagar Pin: 190001 Fax: 0194-2470486; 2477309; Telephone: 2477337; e-mail: [email protected] NHM Help Line for Jammu Division: 18001800104; Kashmir Division: 18001800102 Notice inviting e-Bids for Establishment of ‘Integrated 104 - Centralized Call Center cum Health Desk’ in Jammu & Kashmir on “Build – Operate – Transfer (BOT)” basis For and on behalf of the Hon’ble Lt. Governor of Jammu & Kashmir, online bids are invited for establishment of ‘Integrated 104 - Centralized Call Center cum Health Helpline’ in Jammu & Kashmir on “Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT)” basis, as per detailed specifications and terms & conditions mentioned in this tender document (SBD), for a period of five (5) year(s), extendable on year to year performance of the call centre and subject to annual approval by the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Govt. of India: S. No. Particulars Date/ Time 1 Date of Publishing SBD 15.02.2021 at 1200 Hrs 2 Start Date of Downloading SBD from Website 15.02.2021 from 1200 Hrs 3 Websites for Downloading SBD www.jktenderns.gov.in, www.jknhm.com 4 Last Date of Downloading SBD from Website 20.03.2021 upto 1400 Hrs 5 Seek Clarification Start Date 15.02.2021 from 1400 Hrs 6 Seek Clarification End Date 04.03.2021 upto 1600 Hrs 7 Pre-Bid Meeting 06.03.2021 at 1500 Hrs Conference Hall of -

Everything You Need to Know About Contact Centre Technology Contents

MANA GED SER VICES Everything You Need to Know About Contact Centre Technology Contents Introduction: What is the role of Contact Centre technology? 1. Contact Centre Channels a) Voice / SMS b) Digital and Social c) Chatbots & Virtual Agents 2. Reporting, Compliance & Feedback a) Agent Desktop b) Reporting / Voice of the Customer c) Workforce Optimisation & Management d) Compliance / AI in Contact Centres 3. Selecting Vendors, Partners & Approach a) Uptime & Reliability b) Technology Vendor Selection c) The Journey About Connect Managed Services 2 Introduction: What is the role of Contact Centre Technology? The role of the Contact Centre is evolving at a rapid rate. In the age of Machine Learning (ML), big data and Artificial Intelligence (AI), businesses are finding increasingly innovative ways to utilise the vast amounts of data produced in their Contact Centre environments. Expanding communication channels, automating systems and enhancing customer contact opportunities can offer cost-effective and compliant ways to retain current customers, increase market share and convert calls to sales (and revenue). A complete understanding of all the options along with the current structure of your Contact Centre is the first step towards creating this communications hub of the future. Contact Centre changes are being driven by three broad elements: 1. Customer Experience Revolution 2. Digital Transformation 3. Customer Journey Personalisation Historically, the main goal for call centres was achieving the lowest cost of delivery, which caused businesses to relocate their call centres to evermore inexpensive countries. Call centre agents were not valued, which led to high agent churn – paradoxically a significant cost to any business. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) were focussed on metrics related to cost, with mixed results. -

Call Centre Ease of Communication in Customer Service Delivery: an Asset to Managing Customers' Needs?

“Call centre ease of communication in customer service delivery: an asset to managing customers’ needs?” AUTHORS Devina Oodith Sanjana Brijball Parumasur Devina Oodith and Sanjana Brijball Parumasur (2015). Call centre ease of ARTICLE INFO communication in customer service delivery: an asset to managing customers’ needs?. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 13(2-si), 482-494 RELEASED ON Friday, 28 August 2015 JOURNAL "Problems and Perspectives in Management" FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 0 0 0 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Problems and Perspectives in Management, Volume 13, Issue 2, 2015 SECTION 3. General issues in management Devina Oodith (South Africa), Sanjana Brijball Parumasur (South Africa) Call centre ease of communication in customer service delivery: an asset to managing customers’ needs? Abstract The customer service experience has been equated to a business tsunami as customers switch to those companies that offer greater customer satisfaction. It becomes the task of the firm’s call centre to cradle customer interaction and loyalty through ease and speed of access, quality and ease of communication with call centre agents. This study was undertaken in Durban, South Africa, and was conducted within a Public Sector service environment presenting a twofold agent and customer perspective of how service delivery could be harnessed through ease of communication. The Public Sector service environment comprised of four major call centres employing a total of 240 call centre agents. A sample of 151 call centre agents was drawn using cluster sampling and a 63% response rate was achieved. -

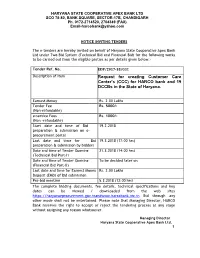

Request for Creating Customer Care Center's (CCC) for HARCO Bank and 19 Dccbs in the State of Haryana

HARYANA STATE COOPERATIVE APEX BANK LTD SCO 78-80, BANK SQUARE, SECTOR-17B, CHANDIGARH Ph. 0172-2714520, 2704349 (FAX) [email protected] NOTICE INVITING TENDERS The e-tenders are hereby invited on behalf of Haryana State Cooperative Apex Bank Ltd under Two Bid System (Technical Bid and Financial Bid) for the following works to be carried out from the eligible parties as per details given below:- Tender Ref. No. EDP/2017-18/CCC Description of Item Request for creating Customer Care Center’s (CCC) for HARCO bank and 19 DCCBs in the State of Haryana. Earnest Money Rs. 2.00 Lakhs Tender Fee Rs. 5000/- (Non-refundable) e-service Fees Rs. 1000/- (Non –refundable) Start date and time of Bid 19.2.2018 preparation & submission on e- procurement portal Last date and time for Bid 19.3.2018 (17:00 hrs) preparation & submission by bidders Date and time of Tender Opening 21.3.2018 (14:00 hrs) (Technical Bid Part-I) Date and time of Tender Opening To be decided later on (Financial Bid Part-II) Last date and time for Earnest Money Rs. 2.00 Lakhs Deposit (EMD) of Bid submission Pre-bid meeting 5.3.2018 (12:00 hrs) The complete bidding documents, fee details, technical specifications and key dates can be viewed / downloaded from the web sites https://haryanaeprocurement.gov.inandwww.harcobank.nic.in Bid through any other mode shall not be entertained. Please note that Managing Director, HARCO Bank reserves the right to accept or reject the tendering process at any stage without assigning any reason whatsoever.