DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Ali'i Drive Banyans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association of Unit Owners Contact List

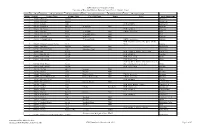

Association of Unit Owners Contact List Project Name/Number AOUO Designated Officer for Direct Contact/Mailing Address Management Company/Telephone Number `AKOKO AT HO`OPILI Reg.# 8073 1001 QUEEN Reg.# 7675 1001 WILDER EMILY PRESIDENT 1001 WILDER #305 HAWAIIAN PROPERTIES, LTD. Reg.# 5 WATERS HONOLULU HI 96822 8085399777 1010 WILDER RICHARD TREASURER 1010 WILDER AVE, OFFICE SELF MANAGED Reg.# 377 KENNEDY HONOLULU HI 96822 8085241961 1011 PROSPECT RICHARD PRESIDENT 1188 BISHOP ST STE 2503 CERTIFIED MANAGEMENT INC dba ASSOCI Reg.# 1130 CONRADT HONOLULU HI 96813 8088360911 1015 WILDER KEVIN PRESIDENT 1015 WILDER AVE #201 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 1960 LIMA HONOLULU HI 96822 8085939100 1037 KAHUAMOKU VITA PRESIDENT 94-1037 KAHUAMOKU ST 3 CEN PAC PROPERTIES INC Reg.# 1551 VILI WAIPAHU HI 96797 8085932902 1040 KINAU PAUL PRESIDENT 1040 KINAU ST., #1206 HAWAIIAN PROPERTIES, LTD. Reg.# 527 FOX HONOLULU HI 96814 8085399777 1041 KAHUAMOKU ALAN PRESIDENT 94-1041 KAHUAMOKU ST 404 CEN PAC PROPERTIES INC Reg.# 1623 IGE WAIPAHU HI 96797 8085932902 1054 KALO PLACE JUANA PRESIDENT 1415 S KING ST 504 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 5450 DAHL HONOLULU HI 96814 8085939100 1073 KINAU ANSON PRESIDENT 1073 KINAU ST 1003 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 616 QUACH HONOLULU HI 96814 8085939100 1108 AUAHI TODD PRESIDENT 1240 ALA MOANA BLVD STE. 200 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 7429 APO HONOLULU HI 96814 8085939100 1111 WILDER BRENDAN PRESIDENT 1111 WILDER AVE 7A HAWAIIAN PROPERTIES, LTD. Reg.# 228 BURNS HONOLULU HI 96822 8085399777 1112 KINAU LINDA Y SOLE OWNER 1112 KINAU ST PH SELF MANAGED Reg.# 1295 NAKAGAWA HONOLULU HI 96814 1118 ALA MOANA NICHOLAS PRESIDENT 1118 ALA MOANA BLVD., SUITE 200 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 7431 VANDERBOOM HONOLULU HI 96814 8085939100 1133 WAIMANU ANNA PRESIDENT 1133 WAIMANU STREET, STE. -

APR 2 0 2005 Sigjfeture Oncertifying Official Date

NFS Form 10-900 / AO^/rS^ OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLA REGISTRATION FORM ^ ^ ^ This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name: Holualoa 4 Archaeological District (State Site No. 50-10-37-23.661) other names/site number: Kamoa Point/Keolonahihi Complex (10-37-2059): Keakealaniwahine Residential Complex (no #): and Kaluaokalani______________ 2. Location street & number Ali'i Drive not for publication city or town Kailua-Kona vicinity ______ state Hawaii code HI county Hawaii zip code 96745 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets __ does not mi National Register Criteria. -

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island Status Key: 1 = Not Hawaiian; 2 = Not Reviewed; 3 = More Research Needed; 4 = HBGN Corrected; 5 = Already Correct in GNIS; 6 = Name Change Status Feat ID Feature Name Feature Class Corrected Name Source Notes USGS Quad Name 1 365008 1940 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 1 365009 1949 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 3 358404 Aa Falls Falls PNH: not listed Kukuihaele 5 358406 ʻAʻahuwela Summit ‘A‘ahuwela PNH Puaakala 3 358412 Aale Stream Stream PNH: not listed Piihonua 4 358413 Aamakao Civil ‘A‘amakāō PNH HBGN: associative Hawi 4 358414 Aamakao Gulch Valley ‘A‘amakāō Gulch PNH Hawi 5 358415 ʻĀʻāmanu Civil ‘Ā‘āmanu PNH Kukaiau 5 358416 ʻĀʻāmanu Gulch Valley ‘Ā‘āmanu Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Kukaiau PNH: Ahalanui, not listed, Laepao‘o; Oneloa, 3 358430 Ahalanui Laepaoo Oneloa Civil Maui Kapoho 4 358433 Ahinahena Summit ‘Āhinahina PNH Puuanahulu 5 1905282 ʻĀhinahina Point Cape ‘Āhinahina Point PNH Honaunau 3 365044 Ahiu Valley PNH: not listed; HBGN: ‘Āhiu in HD Kau Desert 3 358434 Ahoa Stream Stream PNH: not listed Papaaloa 3 365063 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Pahala 3 1905283 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Milolii PNH: not listed; HBGN: Āholehōlua if it is the 3 1905284 ʻĀhole Holua Locale slide, Āholeholua if not the slide Milolii 3 358436 Āhole Stream Stream PNH: Āhole, Maui Papaaloa 4 358438 Ahu Noa Summit Ahumoa PNH Hawi 4 358442 Ahualoa Civil Āhualoa PNH Honokaa 4 358443 Ahualoa Gulch Valley Āhualoa Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Honokaa -

Regional Tsunami Evacuations for the State of Hawaii: a Feasibility Study Based on Historical Runup Data

REGIONAL TSUNAMI EVACUATIONS FOR THE STATE OF HAWAII: A FEASIBILITY STUDY BASED ON HISTORICAL RUNUP DATA Daniel A. Walker Tsunami Memorial Institute 59-530 Pupukea Road Haleiwa, Hawaii 96712 ABSTRACT Historical runup data for the Hawaiian Islands indicate that evacuations of only limited coastal areas, rather than statewide evacuations, may be appropriate for some small tsunamis originating along the Kamchatka, Aleutian, and Alaskan portion of the circum-Pacific arc. With such limited evacuations most statewide activities can continue with little or no disruptions, saving millions in lost revenues and overtime costs, and maintaining or enhancing credibility in state and federal agencies. However, such evacuations are contingent upon accurate real-time modeling of the maximum expected runup values. Also, data indicate that such evacuations may not be appropriate for small Chilean tsunamis. Furthermore, data from other regions are thus far too limited for an evaluation of the appropriateness of partial evacuations for small tsunamis from those regions. Science_of_Tsunami_Hazards,_Vol_22,_No._1,_page_3_(2004) Introduction Historical data indicate that tsunami runups are generally greatest along the northern coastlines of the Hawaiian Islands for earthquake originating in that portion of the circum-Pacific arc from Kamchatka through the Aleutians Islands to Alaska. A critical question is whether a statewide warning should be issued if tide gauge, magnitude, and modeling data predict a maximum runup of only 1 meter for some portions of those northern shores. [A one meter tsunami is generally considered by the scientific community and civil defense agencies to be a potentially life threatening phenomenon requiring a warning, if possible, of its arrival and location.] The answer to the question depends on the accuracy of the prediction and how much smaller the runups might be on those other coastlines. -

Association of Unit Owners Contact List

Association of Unit Owners Contact List Project Name/Number AOUO Designated Officer for Direct Contact/Mailing Address Management Company/Telephone Number 1001 WILDER GAIL PRESIDENT 1001 Wilder, #403 CITY PROPERTIES INC Reg.# 5 LEVY HONOLULU HI 96822 8085241455 1010 WILDER RICHARD TREASURER 1010 WILDER AVE 1602 SELF MANAGED Reg.# 377 KENNEDY HONOLULU HI 96822 8085241961 1011 PROSPECT RICHARD PRESIDENT 1188 BISHOP ST STE 2503 CERTIFIED MGMT INC, DBA ASSOCIA HAW Reg.# 1130 CONRADT HONOLULU HI 96813 8088360911 1015 WILDER LINDA PRESIDENT 1015 WILDER AVE #905 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 1960 FUJITANI HONOLULU HI 96822 8085939100 1037 KAHUAMOKU VITA PRESIDENT 94-1037 KAHUAMOKU ST 3 OISHI'S PROP MGMT CORP Reg.# 1551 VILI WAIPAHU HI 96797 8089499499 1040 KINAU JERRY PRESIDENT 55 S JUDD ST 607 HAWAIIAN PROPERTIES, LTD Reg.# 527 ZAK HONOLULU HI 96817 8085399777 1041 KAHUAMOKU Alan President 94-1041 Kahuamoku Street, #404 CEN PAC PROPERTIES INC Reg.# 1623 Ige Waipahu HI 96797 8085932902 1054 KALO PLACE JUANA PRESIDENT 1415 S KING STREET, #504 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 5450 DAHL HONOLULU HI 96814 8085939100 1073 KINAU ANSON PRESIDENT 1073 KINAU ST #1003 HAWAIIANA MANAGEMENT COMPANY, LTD Reg.# 616 QUACH HONOLULU HI 96814 8085939100 1111 WILDER BRENDAN PRESIDENT 1111 WILDER AVE #7A HAWAIIAN PROPERTIES, LTD Reg.# 228 BURNS HONOLULU HI 96822 8085399777 1112 KINAU LINDA Y SOLE OWNER 1112 KINAU ST PH Reg.# 1295 NAKAGAWA HONOLULU HI 96814 1133 WAIMANU KELFRED PRESIDENT 975 Kapiolani Blvd Ste 200 CITY PROPERTIES INC Reg.# 3335 CHANG Honolulu HI 96814 8085241455 -

Association of Unit Owners Contact List

Association of Unit Owners Contact List Project Name/Number AOUO Designated Officer for Direct Contact/Mailing Address Management Company/Telephone Number 1001 WILDER JOHN PRESIDENT 1001 WILDER AVE #901 CITY PROPERTIES INC Reg.# 5 WRAY HONOLULU HI 96822 8085241455 1010 WILDER EVELYN SECRETARY 1010 WILDER AVE OFC SELF MANAGED Reg.# 377 LANCE HONOLULU HI 96822 8085241961 1011 PROSPECT RICHARD PRESIDENT 1188 BISHOP ST STE 2503 CERTIFIED MGMT INC Reg.# 1130 CONRANDT HONOLULU HI 96813 8088360911 1015 WILDER LINDA PRESIDENT 1015 WILDER AVE #905 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 1960 FUJITANI HONOLULU HI 96822 8085939100 1037 KAHUAMOKU VITA PRESIDENT 94-1037 KAHUAMOKU ST #3 OISHI'S PROP MGMT CORP Reg.# 1551 VILI WAIPAHU HI 96797 8089499499 1040 KINAU JERRY PRESIDENT 55 S JUDD ST #607 HAWAIIAN PROPERTIES LTD Reg.# 527 ZAK HONOLULU HI 96817 8085399777 1041 KAHUAMOKU ALLAN PRESIDENT 94-1041 KAHUAMOKU ST #404 CEN PAC PROPERTIES INC Reg.# 1623 IGE WAIPAHU HI 96797 8085932902 1054 KALO PLACE PETER B PRESIDENT 931 UNIVERSITY AVE #105 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 5450 SAVIO HONOLULU HI 96826 8085939100 1073 KINAU ROBERT V PRESIDENT 1073 KINAU ST #1101 HAWAIIANA MGMT CO LTD Reg.# 616 CHAR SR HONOLULU HI 96814 8085939100 1111 WILDER BRENDAN PRESIDENT 1111 WILDER AVE #7A HAWAIIAN PROPERTIES LTD Reg.# 228 BURNS HONOLULU HI 96822 8085399777 1112 KINAU LINDA SOLE OWNER 1112 KINAU ST PH SELF MANAGED Reg.# 1295 JOHNSTON HONOLULU HI 96814 8085457816 1133 WAIMANU JEFFREY PRESIDENT 1133 WAIMANU ST #2008 CITY PROPERTIES INC Reg.# 3335 BERMAN HONOLULU HI 96814 8085241455 -

Environmental Assessment

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT NEW PARK DEVELOPMENT ALI’I KAI SUBDIVISION HOLUALOA, NORTH KONA, HAWAII TMK: (3) 7-6-19:034 Prepared for: The Department of Parks and Recreation County of Hawai`i Prepared by: AES Design Group, Inc. July 19, 2010 Environmental Assessment Ali`i Kai Subdivision New Park Development - TMK: (3) 7-6-19:034 Holualoa, North Kona, Hawai`i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 PROJECT DATA ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 PURPOSE OF ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT ........................................................................... 1-2 1.3 GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED ACTION ........................................................................ 1-2 1.4 FUNDING SOURCES................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.5 TIME FRAME............................................................................................................................. 1-2 1.6 REQUIRED PERMITS .................................................................................................................. 1-3 1.7 AGENCIES CONSULTED............................................................................................................. 1-3 1.8 COMMUNITY INPUT AND PARTICIPATION ................................................................................ -

Big Island Dining • Art • Shopping 2020 Media

Art “We BEACH GUIDE BEACH ARTISTS & GALLERIES & ARTISTS WAILEA do not remember not do • Shopping M • four seasons resort maui at wailea at maui resort seasons four Dining DINING & SHOPPING REVIEWS SHOPPING & DINING ay 2019 2019 ay Spago by Wolfgang Puck Wolfgang by Spago • Days, HISTORY A we remember we • ENTERTAINMENT J uly 2019 J une 2020 • pril 2020 pril Lifestyle Moments.” • WAILEA MAP WAILEA UPCOUNTRY Cesare Pavese Cesare • GOLF MAGAZINE PA‘IA • MAKAWAO • KULA • HA‘IKU • HAˉ NA F ebruary 2020 J J anuary 2021 une 2019 DiningKIHEI & Shopping LahainaM ay 2020 ArtDining & Shopping Lahaina • Ka‘anapali D Kaua‘iECEMBER 2018 to Kapalua BIG ISLAND Art Dining A Nourishingugust Kaua‘i 2019 “We Dining Reviews • N do not Shopping OVEMBER 2019 ekolu kitchen remember O PRAH ’ S B OUNTIFUL L IFE IN M AUI • Hawaiian History BEACH GUIDE • DINING & SHOPPING REVIEWS Historic Little Towns HALEAKALAˉ • ROAD TO HAˉ NA • TOWNS • FARMS • ART • WINERYArt • MAPS Dining1279. .a culinary voyage • “Look deep into Nature, and then you will AQUARIUM Days, J The Banyan Tree at The Ritz Carlton, Kapalua Understand everything Better.”Albert Einstein • WHALE SANCTUARY DININGBEACHES & SHOPPING REVIEWS uly 2020 • ANCIENT HAWAIIAN FISHPOND we remember • • “One cannot GOLF • Golf • • LOCAL HISTORY Shopping MAPS • • Think ConciergeBeaches “Bucket List” if one has not • SIGHTS TO VISIT well, • ART Moments.” Love • MAPS Dined • well, Island Maps well.” Sleep • EVENTS BIG VirginiaISLAND Woolf well, Cesare Pavese Dining IRONMANKILAUEA VOLCANO “We do not remember • AUGUST• Art 2020 - JULY 2021FARMERS EDITION MARKETS • HISTORY • Shopping Days, Magazine • • HULA SERVING HAWAI‘I FOR 39 YEARSwe remember PETROGLYPHS THE ONLY VISITOR MAGAZINE DEVOTED • Media Kit ISLAND MAPS TO EVERY SECTION OF THE BIG ISLAND Moments.” • BEACHES Cesare Pavese A ugust 2019 J uly 2020 BIG VISITOR BIG ISLAND Dining ISLAND #1 MAGAZINE Art • Shopping The ONLY Dining & Shopping Magazine KILAUEA VOLCANO • HISTORY • HULA • ISLAND MAPS devoted to Your Geographic Area. -

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce § 226.201

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce § 226.201 § 226.201 Critical habitat for the Ha- (vii) Gardner Pinnacles, waiian monk seal (Neomonachus (viii) French Frigate Shoals, schauinslandi). (ix) Necker Island, and Critical habitat is designated for Ha- (x) Nihoa Island. waiian monk seals as described in this (2) Main Hawaiian Islands: Hawaiian section. The textual descriptions of monk seal critical habitat areas sur- critical habitat in this section are the rounding the following islands listed definitive source for determining the below are defined in the marine envi- critical habitat boundaries. ronment by a seaward boundary that (a) Critical habitat boundaries. Critical extends from the 200-m depth contour habitat is designated to include all line (relative to mean lower low water), areas in paragraphs (a)(1) and (2) of this including the seafloor and all sub- section and as described in paragraphs surface waters and marine habitat (b)(1) and (2) of this section: within 10 m of the seafloor, through (1) Northwestern Hawaiian Islands: the water’s edge into the terrestrial en- Hawaiian monk seal critical habitat vironment where the inland boundary areas include all beach areas, sand extends 5 m (in length) from the shore- spits and islets, including all beach line between identified boundary points crest vegetation to its deepest extent listed in the table below around the inland, lagoon waters, inner reef areas listed in paragraphs (a)(2)(i)–(vi) waters, and including marine habitat of this section. The shoreline is de- through -

Tsunami Deposits at Queen's Beach, Oahu, Hawaii

ISSN 8755-6839 SCIENCE OF TSUNAMI HAZARDS The International Journal of The Tsunami Society Volume 22 Number 1 Published Electronically 2004 REGIONAL TSUNAMI EVACUATION FOR THE STATE OF HAWAII: A FEASIBILITY STUDY BASED ON HISTORICAL RUNUP DATA 3 Daniel A. Walker Tsunami Memorial Institute Haleiwa, Hawaii, USA TSUNAMI DEPOSITS AT QUEEN’S BEACH, OAHU, HAWAII INITIAL RESULTS AND WAVE MODELING 23 Barbara Keating University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA Franziska Whelan University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany Julie Bailey-Brock University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA TSUNAMI GENERATED BY THE VOLCANO ERUPTION ON JULY 12-13, 2003 AT MONTSERRATE, LESS ANTILLES 44 Efim Pelinovsky Institute of Applied Physics, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia Narcisse Zahibo Universite Antilles Guyane, Pointe-a-Pitre, France Peter Dunkley, Marie Edmonds, Richard Herd Montserrat Volcano Observatory, Montserrat Tatiana Talipova Institute of Applied Physics, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia Andrey Kozelkov and Irina Nikolkina State Technical University, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia copyright c 2004 THE TSUNAMI SOCIETY P. O. Box 1130, Honolulu, HI 96807, USA WWW.STHJOURNAL.ORG OBJECTIVE: The Tsunami Society publishes this journal to increase and disseminate knowledge about tsunamis and their hazards. DISCLAIMER: Although these articles have been technically reviewed by peers, The Tsunami Society is not responsible for the veracity of any state- ment, opinion or consequences. EDITORIAL STAFF Dr. Charles Mader, Editor Mader Consulting Co. 1049 Kamehame Dr., Honolulu, HI. 96825-2860, USA EDITORIAL BOARD Mr. George Curtis, University of Hawaii - Hilo Dr. Hermann Fritz, Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Galen Gisler, Los Alamos National Laboratory Dr. Zygmunt Kowalik, University of Alaska Dr. Tad S. Murty, Baird and Associates - Ottawa Dr. -

Royal Footsteps Along the Ko

Kona Kai `Ōpua Ha`aheo Hawai`i i na Kona Proud is Kona of Hawai`i Ka wai kau i ka maka ka `ōpua The waters and thick clouds Hualalai kau mai i luna Hualālai, the majestic mountain is high above Ka heke ia o na Kona Kona is the best He `āina wela i`o o na Kona This warm land E ka makani ahe olu wai With the refreshing wind `O ka pa konane ahe kehau The bright moonlight that I ka ili o ka malihini Beckons the visitors Hui: Chorus: Hanohano Proud `O Kona kai `ōpua i ka la`i The cloud banks over Kona's peaceful sea `O pua hinano i ka mālie Like the hinano flower Wai na lai In the peaceful sea Ka mako a `ōpua The cloudbanks of Kona `A`ole no ahe lua a`e like aku ia Are incomparable, second to none Me Kona kai `ōpua The cloudbanks of Kona Ke kai ma`oki`oki The streaked sea Ke kai malino a`o Kona` The peaceful sea of Kona Kona kai `ōpua i ka la`i The cloud bank over Kona's peaceful sea `O pua hinano i ka mālie Like the hinano flower in the calm Holo na wai a ke kehau Where dusk descends with evening dew Ke na`u wai la nā kamali`i The na`u is chanted by the playful children Kāohi ana i ke kukuna lā Hold back the rays of the sun Ku`u la kolili i ka`ili kai The sun rays reflecting on the surface of the sea Pumehana wale ho`i ia `āina Very warm is the land Aloha no kini a`o Ho`olulu Very loving the Ho`olulu progeny `A`ohe lua ia `oe ke aloha Nothing compares to the love O ku`u puni o ka mea `owa O my beloved companion of all time Ha`ina ka inoa o ku`u lani For my lovely chief, my last refrain No Liholiho no la inoa Liholiho, I praise your name This mele (song) tells of a love affair between Liholiho (Kamehameha II) and a woman of rank. -

Corridor Management Plan Appendices

Royal Footsteps Along the Kona Coast Appendices A ‐ References B ‐ Glossary C ‐ Ali‘i Drive Survey ‐ 2003 D ‐ Traffic Assessment Report for Ali‘i Drive ‐ 2007 E ‐ Interim Preservation Plan (Draft) F ‐ Interpretive Content: Royal Footsteps Story Themes G ‐ Institutional Partners Meetings H ‐ Crash Data I ‐ Public Access to Shoreline Along Ali‘i Drive J ‐ Statements of Support Royal Footsteps Along the Kona Coast Corridor Management Plan ‐ Appendices Royal Footsteps Along the Kona Coast Appendix A ‐ References Royal Footsteps Along the Kona Coast Corridor Management Plan ‐ Appendices References: This Corridor Management Plan (CMP) is not intended to serve as a technical, reference document. Instead, it is a management plan and tool for the implementation of the Royal Footsteps Along the Kona Coast. This CMP has incorporated information from many different sources that, in most cases, involved copy‐paste and various edits of text from these sources. The following sources served as the basis for much of the background, historical, etc, information used in the CMP: Ballot, Howard G. and Carter, George R. ‐ The History of the Hawaiian Mission Press, with a Bibliography of the Earlier Publications. 1845 Barrere, Dorothy; Kamehameha in Kona: Two Documentary Studies, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, 1975 Bezona, Norm; Banyans‐landmark trees which need protection, West Hawaii Today, September 13, 1989 Bingham, Hiram; A Residence of Twenty‐One Years in the Sandwich Islands, 1847, Digitized by Google Bingham, Sybil Moseley; Unpublished Journal, 1819‐1923 BishopMuseum.org, Amy B.H. Greenwell Ethnobotanical Garden; The Kona Field System Bishop, Sereno Edward; Reminiscences of Old Hawaii; 1916, Digitized by Google Bryan, Alanson Bryan; Natural History of Hawaii, 1915, Digitized by Google Clark, John R.K.; Beaches on the Big Island, 1985 Clark, John R.K.; Hawaii Place Names: Shores, Beaches, and Surf Sites, 2002 Cordy, Ross; Exalted Sits the Chief, 2000 County of Hawaii; Alii Drive Realignment, P‐2093, Federal Aid Project No.