189-193, 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity and Language of Tamil Community in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges

DOI: 10.7763/IPEDR. 2012. V48. 17 Identity and Language of Tamil Community in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges + + + M. Rajantheran1 , Balakrishnan Muniapan2 and G. Manickam Govindaraju3 1Indian Studies Department, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2Swinburne University of Technology, Sarawak, Malaysia 3School of Communication, Taylor’s University, Subang Jaya, Malaysia Abstract. Malaysia’s ruling party came under scrutiny in the 2008 general election for the inability to resolve pressing issues confronted by the minority Malaysian Indian community. Some of the issues include unequal distribution of income, religion, education as well as unequal job opportunity. The ruling party’s affirmation came under critical situation again when the ruling government decided against recognising Tamil language as a subject for the major examination (SPM) in Malaysia. This move drew dissatisfaction among Indians, especially the Tamil community because it is considered as a move to destroy the identity of Tamils. Utilising social theory, this paper looks into the fundamentals of the language and the repercussion of this move by Malaysian government and the effect to the Malaysian Indians identity. Keywords: Identity, Tamil, Education, Marginalisation. 1. Introduction Concepts of identity and community had been long debated in the arena of sociology, anthropology and social philosophy. Every community has distinctive identities that are based upon values, attitudes, beliefs and norms. All identities emerge within a system of social relations and representations (Guibernau, 2007). Identity of a community is largely related to the race it represents. Race matters because it is one of the ways to distinguish and segregate people besides being a heated political matter (Higginbotham, 2006). -

Nanyang Siang Pau Highlights: Tuesday, Jan. 27 27 January 1998

NANYANG SIANG PAU HIGHLIGHTS: TUESDAY, JAN. 27 27 JANUARY 1998 1. KUALA LUMPUR: Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr. Mahathir Mohamad says the government has good strategy to help economic recovery but it takes time and needs the co-operation of the people particularly the commercial sector. In his Hari Raya Puasa message, he says if the people co-operate fully with the government, the economy will recover soon. Page 1. Lead story 2. KUALA LUMPUR: US ambassador to Malaysia John Malot says he has a good formula to attract large amount of American investments to Malaysia. He feels if they are allowed to invest in the markets services, financial and manufacturing sectors, American investors will invest in Malaysia in large numbers. Page 1 3. KUALA LUMPUR: Revenue derived from palm oil is expected to reach RM15.6 billion this year. Primary Industries Minister Datuk Seri Dr. Lim Keng Yaik said the demand for vegetable oil has increased following the El Nino disaster. Palm oil now fetches between RM2,300 and RM2,600 per tonne compared to RM1,200 per tonne previously. Page 2 4. KUALA LUMPUR: Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim says all state governments should adopt the open registration system for low-cost house buyers to ensure only those who are really qualified can buy such houses. The government has received numerous complaints that low-cost houses had been sold to underserving cases. Page 2 5. KUALA LUMPUR: The government has recognised pharmacy degree from Taiwan's National University. Health Minister Datuk Chua Jui Meng says graduates who obtained the degree after July 4 last year and complied with the required regulations may register themselves. -

To: Bernama Business Times (New Straitstimes) Sin Chevu Jit Poh

EcIMB FOR IMruED|ATE RELEASE Date: 2 June 2028 , To: At&ntiron: Securities Cornmission Malaysia Puan Seri lzriana Mdani Mohtar Bursa Mataysia Securities Berhad Team 3 Tasek Corporation Bertrad Ms Go Hooi Koon Berita Harian En Kamarul Zaidi Bernama . Ms Saraswathi Muniappan Business Times (New StraitsTimes) En ZuraimiAbdullah The Star Mr Jagdev Singh Sidhu The Malaysian Reserve En- Mohamad Adan Jaatar Nanyang Siang Pau Mr Ha Kok Mun Sin Chevu Jit Poh {Malaysia} Ms Lor Sor Wan The Sun Mr Lee Weng Khren The Edge Markets The Editor *JOINT HL CEIIENT (UAI-AYSIA) SDN BHD A],ID RIDGE STA,R UilllTEB {COLLECTIVELY, THE OFFERORS'} UNCONBITIONAL VOLUHTARY TAKE€VER OFFER BY THE JOIHT OFFERORS THRGJGH CITB INVE$TIIENT BANK BERHAD TO ACQUIRE ALL THE REMAIHIHG ORDINARY SHARES (EXCLUDTNG TREASURY SHARES) ('OFFER ORDTNARY SHARES'I AHD ALL THE REMA|N|NG PREFERENCE SHARES {*OFFER PREFERENCE SHARES"} tN TASEK CORPORATTON BERHAD ("TASEK') l*CrT ALREADY HELD BY THE JOTNT OFFERORS FOR A CASH CONSTDERATTON OF RS5.8II PER OFFER ORIXNARY SHARE AXD RH5.S0 pER OFFER PREFEREHCE SHARE *oFFEtr) {THE - DISCLOSURE OF DEALINGS }N ACCORDANCE WITH RULE {9 OF THE RULES ON TAKE- ovERs, HTERGERS AND COTiPULSORY ACQU|S|nONS {'RULES',} We refurto the Notice of the Offer dated 12 May 2020 and Tasek's announcement on the same day. Pursuant to Rule 19.M(1) of the Rules, on behalf of the Joint Ofierors, we wish ta inform that one of the Joint Offerors, Ridge Star Limited, has dealt in the securiEes of Tasek, detaits of whic*r are as follows: Deseription of Description of Date Name transaction security Quartifi, Price {RHl 2 Jure 2020 Rktge Star l-imited Buy Ordinary Shares 30,500 5.79 CIMB lnvestment Bank Berhad (184r7-M) lTthFloor MenaraC|MB No. -

Why Celebrate Chennai?

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/18-20 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/18-20 Publication: 1st & 16th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) INSIDE Short ‘N’ Snappy Museum Theatre gate Mesmerism in Madras Tamil Journalism Thrilling finale www.madrasmusings.com WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI Vol. XXIX No. 8 August 1-15, 2019 Why celebrate Chennai? every three minutes that places by The Editor us ahead of Detroit? When it comes to leather exports did we Our THEN is a sketch by artiste Vijaykumar of old Woodlands here we go again, ask- other to the problems it faces. know that Chennai and Kan- hotel, Westcott Road, where Krishna Rao began the first of his ing everyone to celebrate This is where we ply our trade, pur are forever neck-to-neck T restaurant chain in the 1930s. Our NOW is Saravana Bhavan Chennai, for Madras Week is educate our children, practise for reaching the top slot? And (Courtesy: The Hindu) also equally significant in Chennai’s food just around the corner. The our customs, celebrate our our record in IT is certainly history but whose owner died earlier this month being in the news cynics we are sure, must be individuality and much else. impressive. If all this was not till the end for wrong reasons. already practising their count- Chennai has given us space for enough, our achievements in er chorus beginning with the all this and we must be thankful enrolment for school education usual litany – Chennai was not for that. -

When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950S and 1960S

China Perspectives 2020-1 | 2020 Sights and Sounds of the Cold War in Socialist China and Beyond When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950s and 1960s Emily Wilcox Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/9947 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.9947 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2020 Number of pages: 33-42 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Emily Wilcox, “When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950s and 1960s”, China Perspectives [Online], 2020-1 | 2020, Online since 01 March 2021, connection on 02 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ chinaperspectives/9947 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.9947 © All rights reserved Special feature china perspectives When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950s and 1960s EMILY WILCOX ABSTRACT: This article challenges three common assumptions about Chinese socialist-era dance culture: first, that Mao-era dance rarely circulated internationally and was disconnected from international dance trends; second, that the yangge movement lost momentum in the early years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC); and, third, that the political significance of socialist dance lies in content rather than form. This essay looks at the transformation of wartime yangge into PRC folk dance during the 1950s and 1960s and traces the international circulation of these new dance styles in two contexts: the World Festivals of Youth and Students in Eastern Europe, and the schools, unions, and clan associations of overseas Chinese communities in Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, and San Francisco. -

The Survival of Malaysia's National Television Within a Changing

The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, Vol. 16(3), 2011, article 2. The Survival of Malaysia’s National Television Within a Changing Mediascape Fuziah Kartini Hassan Basri Abdul Latiff Ahmad Emma Mirza Wati Mohamad Arina Anis Azlan Hasrul Hashim School of Media and Communication Studies Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 43600. Bangi Selangor MALAYSIA The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, Vol. 16(3), 2011, article 2. The Survival of Malaysia’s National Television Within a Changing Mediascape Fuziah Kartini Hassan Basri, Abdul Latiff Ahmad, Emma Mirza Wati Mohamad, Arina Anis Azlan and Hasrul Hashim ABSTRACT National television is the term used to describe television broadcasting owned and maintained for the public by the national government, and usually aimed at educational, informational and cultural programming. By this definition, Radio Televisyen Malaysia’s TV1 is the national television in Malaysia and until 1984 was the only television broadcast offered to Malaysians. With the privatization policy, new and private stations were established, and RTM eventually faced competition. The advent of direct satellite broadcasting saw another development in the country—the establishment of Astro in 1998. The direct-to-user satellite broadcaster currently carries over 100 channels, including 8 HD channels, thus creating many more choices for viewers. More importantly, Astro carries the global media directly into our homes. International offerings such as CNN, BBC, CCTV, HBO, MTV, FOX, ESPN, Star Sports, and Star World are now within the push of a button for most Malaysians. Astro is a success story, but there were also a few failed attempts along the way such as MetroVision, MegaTV and MiTV. -

The S. Rajaratnam Private Papers

The S. Rajaratnam Private Papers Folio No: SR.151 Folio Title: Newspaper Articles 1) Israel Jews 2) Ghafar Baba 3) Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia – Ties and Languages 4) Lee Kuan Yew ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS New Nation article titled "Marshall helped Jews in SR.151.001 29/11/1978 Digitized Open China" SR.151.002 20/7/1993 Newspaper article titled "Bhangra the British way" Digitized Open ST article titled "Anti-Semitism 'still exists in everyday SR.151.003 8/10/1991 Digitized Open life' in Soviet Union" ST article titled "Jewish group accuses Muslims of SR.151.004 23/9/1991 Digitized Open damaging Temple Mount site" SR.151.005 22/7/1991 Newsweek article titled "The intermarrying kind" Digitized Open The Straits Times article titled "Harsh curfew in West SR.151.006 7/2/1991 Digitized Open Bank and Gaza eased" I.H.T article titled "The talented immigrants bring a SR.151.007 8/12/1990 Digitized Open delicious dream" (8-9 Dec 1990) NST article titled "Disturbing legacy of Rabbi Meir SR.151.008 25/11/1990 Digitized Open Kahane" The Straits Times article titled "Keep the occupied SR.151.009 20/11/1990 Digitized Open land for Jewish migrants: Shamir" SR.151.010 19/11/1990 Time article titled "Where hatred begets hatred" Digitized Open I.H.T article titled "The talented immigrants bring a SR.151.011 8/11/1990 Digitized Open delicious dream" SR.151.012 29/10/1990 Time article titled "How Israel is like Iraq" Digitized Open 1 of 7 The S. -

22 Februari 2019

LAPORAN LIPUTAN MEDIA HARIAN JUMAAT 22 FEBRUARI 2019 BIL TAJUK KERATAN AKHBAR KEMENTERIAN / JABATAN / AGENSI 1. AGRICULTURE MINISTER: DID NOT TERMINATE FISHERMEN’S LIVING ALLOWANCE, NATIONAL, KEMENTERIAN PERTANIAN DAN INDUSTRI ASAS TANI NANYANG SIANG PAU -A4 (MOA) 2. AGRICULTURE MINISTER: 2 NEW VARIETIES TO BE PROVIDED IN NEXT QUARTER FOR ALL PADDY FARMERS, NATION, KWONG WAH YIT POH -A8a 3. AGRICULTURE MINISTER: CONTINUE TO ISSUE FISHERMEN’S LIVING ALLOWANCE, NATION, KWONG WAH YIT POH -A8b 4. TRUST FUND FOR FISHERMEN’S WELLBEING TO BE SET UP, SAYS SALAHUDDIN, HOME, BORNEO POST (KUCHING) -14 5. PUTRAJAYA TO SET UP TRUST FUND FOR FISHERMEN’S WELFARE, SAYS SALAHUDDIN, MALAYSIA KINI -ONLINE 6. SELAMI JIWA NELAYAN, WARGA TANI, NASIONAL, SH -46 7. CONTINUES TO DISTRIBUTE LIVING AID TO FISHERMEN, NATION, SIN CHEW DAILY -4 8. BIONEXUS CONCEPT EXPANDED TO AGRICULTURE, BUSINESS, NEW SARAWAK TRIBUNE -B2 BAKA LEMBU TENUSU: ANGKASA, KOMARDI METERAI MoU, DALAM NEGERI, UM -10 9. 10. ALIEN FISH DEVOURING LOCAL SPECIES IN SG PAHANG, NEWS / NATION, NST -10 JABATAN PERIKANAN MALAYSIA (DOF) 11. SWISS EXPERT FEARS FOR LOCAL FISH SPECIES, NEWS / NATION, NST -10 12. HOBBYISTS SHOULD NOT DUMP ALIEN FISH IN RIVERS, NATION / NEWS, NST -11 13. CADANG WUJUD KUMPULAN WANG AMANAH NELAYAN, DALAM NEGERI, UM -45 LEMBAGA KEMAJUAN IKAN MALAYSIA (LKIM) 14. KERAJAAN AKAN TUBUHKAN KUMPULAN WANG AMANAH NELAYAN, EKONOMI, UTUSAN SARAWAK -1 15. KWAN BANTU NELAYAN TIDAK UPAYA KE LAUT, DASAR & PENTADBIRAN, BH -8 16. TRUST FUND TO ENSURE FISHERMEN’S WELL – BEING, NEWS, NEW SARAWAK TRIBUNE -9 17. RICE YIELD TO INCREASE WITH NEWLY – INTRODUCED VARIETIES, NEWS, KL SCREENER -10 LEMBAGA KEMAJUAN PERTANIAN MUDA (MADA) 18. -

The Premier Green Building Exhibition for Southeast

YOUR GATEWAY TO SOUTHEAST ASIA! THE PREMIER GREEN BUILDING EXHIBITION FOR SOUTHEAST ASIA 1- 3 September 2014 Singapore Held in conjunction with Organised About BEX Asia Build Eco Xpo (BEX) Asia is Southeast Asia’s premier business platform for the green building and construction industry. It is an all-in-one showcase for state-of-the-art green building solutions, where international brands feature their latest technologies and sustainable designs of building products & services. The event congregates global green building solution providers & leading industry players for the Southeast Asian community of architects, engineers, contractors, developers, building owners and consultants. Since 2009, BEX Asia has taken the lead with Singapore, to be the premier green building platform and exhibition for the Southeast Asian marketplace. BEX Asia is typically scheduled over the course of 3 business working days, held in conjunction with the International Green Building Conference (IGBC) organised by BCA/SGBC, during the Singapore Green Building Week (SGBW), where international policy-makers, academics and green building professionals congregate together in Singapore, to engage in a dialogue of green possibilities for the global green movement. Moving forward into the BEX Asia 2014th edition, BEX Asia aims to proactively enhance its international stature, to offer regional visitors an array of international brands/ pavilions on the showfloor. More than 300 exhibitors from over 40 countries; and more than 10,000 industry professionals from across -

Open LIM Doctoral Dissertation 2009.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications BLOGGING AND DEMOCRACY: BLOGS IN MALAYSIAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Ming Kuok Lim © 2009 Ming Kuok Lim Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Ming Kuok Lim was reviewed and approved* by the following: Amit M. Schejter Associate Professor of Mass Communications Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Richard D. Taylor Professor of Mass Communications Jorge R. Schement Distinguished Professor of Mass Communications John Christman Associate Professor of Philosophy, Political Science, and Women’s Studies John S. Nichols Professor of Mass Communications Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This study examines how socio-political blogs contribute to the development of democracy in Malaysia. It suggests that blogs perform three main functions, which help make a democracy more meaningful: blogs as fifth estate, blogs as networks, and blogs as platform for expression. First, blogs function as the fifth estate performing checks-and-balances over the government. This function is expressed by blogs’ role in the dissemination of information, providing alternative perspectives that challenge the dominant frame, and setting of news agenda. The second function of blogs is that they perform as networks. This is linked to the social-networking aspect of the blogosphere both online and offline. Blogs also have the potential to act as mobilizing agents. The mobilizing capability of blogs facilitated the mass street protests, which took place in late- 2007 and early-2008 in Malaysia. -

LEA-MEDIA-KIT-.Pdf

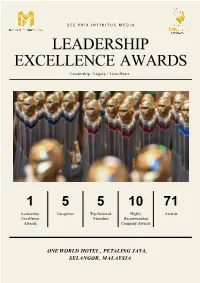

DES PRIX INFINITUS MEDIA LEADERSHIP EXCELLENCE AWARDS Leadership / Legacy / Lion-Heart 1 5 5 10 71 Leadership Categories Top Selected Highly Awards Excellence Awardees Recommended Awards Company Awards ONE WORLD HOTEL , PETALING JAYA, SELANGOR, MALAYSIA LEADERSHIP EXCELLENCE AWARDS Des Prix Infinitus Media Leadership Excellence Awards (LEA) recognizes outstanding leaders and achievements across the Malaysia National Key Economic Areas (NKEA). Leadership Excellence Awards (LEA) works as an independent and non-partisan accreditation body with interest to connect, recognize and help empower leaders across the ASEAN region. Leadership Excellence Awards (LEA) is about bringing people together and promote cross-industry dialogues and pollination. We hope in the next five years; we can host, connect and recognize leaders across ASEAN, providing them with an avenue to network and tell their stories. Malaysia as a nation has come far since its independence, but the success of the country will not take place without the great leaders propelling industries - both in private and public sectors. LEADERSHIP EXCELLENCE AWARDS C AT E G O R I E S LEA features five distinctive categories with the aim to recognise talents and leaders of all walks of life. Feel free to nominate yourself or others if any of the categories below resonate strongly with you. +603 - 5870 3168 | www. dpimedia. com. my C - SUITE LEADERSHIP EXCELLENCE AWA R D S LEA seeks to recognise transformative C-Level leaders with proven track-records in shaping industries and the nation. The nominated individual and/or organisation must have demonstrated a high level to transformation efforts in theirs respective domain of experise. -

Representation of a Minority Community in a Malaysian Tamil Daily

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 9 : 3 March 2009 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. K. Karunakaran, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. REPRESENTATION OF A MINORITY COMMUNITY IN A MALAYSIAN TAMIL DAILY Ponmalar N. Alagappar, MBA., Ph.D. Candidate Maya Khemlani David, Ph.D Sri Kumar Ramayan, M.Comm. Language in India www.languageinindia.com 128 9 : 3 March 2009 Representation of a Minority Community in a Malaysian Tamil Daily Ponmalar, MBA, Ph.D. Candidate, Maya Khemlani David, Ph.D., and Sri Kumar Ramayan, M.Comm. REPRESENTATION OF A MINORITY COMMUNITY IN A MALAYSIAN TAMIL DAILY PONMALAR N. ALAGAPPAR, MBA, Ph.D. Candidate MAYA KHEMLANI DAVID, Ph.D SRI KUMAR RAMAYAN, M.Comm. ABSTRACT The media plays an important role in shaping attitudes of people but, at the same time, the media represents what occurs at ground level. This study examines the coverage of news stories in one Malaysian Tamil daily i.e., Malaysian Namban in August 2007, October 2007 and November 2007. This period encompasses the period just before and during the first month of the Hindu Rights Action Force (Hindraf) movement. Hindraf is a fairly new coalition of 30 Hindu Non-Governmental organizations committed to the preservation of Hindu community rights and heritage in multiracial Malaysia. The Tamils comprise 90% of the Malaysian Indian population and members of Hindraf are mainly Tamils.