Amicus Brief, and Takes No Position

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Eazy E Nwa Diss

Eazy e nwa diss Eazy E Leader Of NWA And Owned Of RUTHLESS Records. Dissing Dr Dre And Snoop Doggy Dogg. Here's a classic diss song from Compton Legend Eazy-E Feat B.G. Knocc Out & Dresta - Real. Eazy-E Dissed Ice Cube (Ice Crumbles) [Unreleased Eazy-E Songs]. Hip-Hop Ice Cube and Dr. Dre had. Ice Cube didn't hold back against his former N.W.A. pals after Ice Cube and the other members: Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, DJ Yella and MC Ren. "No Vaseline" is a diss track by Ice Cube from his second album, Death Certificate. The song was produced by Ice Cube and Sir Jinx. The UK release of Death Certificate omitted this song, along with the second long "Black Korea". The song contains vicious lyrics towards Ice Cube's former group, N.W.A, Dr. Dre and his protégé Snoop Dogg later dissed Eazy-E in the song "Fuck Information · Aftermath · In popular culture · Samples. MC Ren shares the family aspects of N.W.A even as former member MC Ren Explains Why N.W.A Didn't Record Ice Cube Diss Track After "No Vaseline" .. I think Ren should have done more interviews about Eazy E and. As most know by now Eric 'Eazy E' Wright and Andre 'Dr. Dre' Young were with Eazy E and together with Ice Cube and MC Ren they formed NWA. From harmless diss records like Kokane and Above The Law's “Don't. N.W.A is back in this motherfucker / And this is only the single / Wait until the motherfucking album comes out Real Niggaz. -

Summer Savage Challenge

S U M Awwwww SNAP. M Finish line, here we WELCOME E come! It's Week 4! R S A WE READY!! V TO WEEK 4 BRING IT ON! A G E L E T ' S G O O O O ! ! ! ! ! Y E S , I K N O W ! C O M P E T I T I O N ? H O W T O E N T E R C Did somebody say week We have leveled If you haven't submitted It's simple: H 4?? up...quarantine edition. Let's those before photos, 1.Take 3 before and A make sure that we don't go you've still got time! after photos (front, L back to what is "familiar". We side and back) Wow, time has literally @ have to continue to rise to a We will start collecting 2.Submit photos to L flown by. This is the last new level. perspective and s E after photos on Monday, [email protected] a week of our Summer discipline. r a May 4th. N Savage 30 day l o Now that we've improved G challenge. I am so glad I v Don't forget, best before our fitness life, what other e was able to share this E areas in your life need and after photos win a s experience with you. t improvement? PRIZE! y l e S U D I S C L A I M E R M M E Sara Lovestyle (Sara Hood) strongly recommends that you consult with your physician before beginning any exercise program. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Gold & Platinum Awards June// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17

GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS JUNE// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 34 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// We Own It R&B/ 6/27/2017 2 Chainz Def Jam 5/21/2013 (Fast & Furious) Hip Hop 6/27/2017 Scars To Your Beautiful Alessia Cara Pop Def Jam 11/13/2015 R&B/ 6/5/2017 Caroline Amine Republic Records 8/26/2016 Hip Hop 6/20/2017 I Will Not Bow Breaking Benjamin Rock Hollywood Records 8/11/2009 6/23/2017 Count On Me Bruno Mars Pop Atlantic Records 5/11/2010 Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 How Deep Is Your Love Pop Columbia 7/17/2015 Disciples This Is What You Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 Pop Columbia 4/29/2016 Came For Rihanna This Is What You Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 Pop Columbia 4/29/2016 Came For Rihanna Calvin Harris Feat. 6/19/2017 Blame Dance/Elec Columbia 9/7/2014 John Newman R&B/ 6/19/2017 I’m The One Dj Khaled Epic 4/28/2017 Hip Hop 6/9/2017 Cool Kids Echosmith Pop Warner Bros. Records 7/2/2013 6/20/2017 Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 9/24/2014 6/20/2017 Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 9/24/2014 www.riaa.com // // GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS JUNE// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17 6/20/2017 Starving Hailee Steinfeld Pop Republic Records 7/15/2016 6/22/2017 Roar Katy Perry Pop Capitol Records 8/12/2013 R&B/ 6/23/2017 Location Khalid RCA 5/27/2016 Hip Hop R&B/ 6/30/2017 Tunnel Vision Kodak Black Atlantic Records 2/17/2017 Hip Hop 6/6/2017 Ispy (Feat. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Post Malone Announces North American Tour with 21 Savage and Special Guest Sob X Rbe

POST MALONE ANNOUNCES NORTH AMERICAN TOUR WITH 21 SAVAGE AND SPECIAL GUEST SOB X RBE Tickets On Sale to General Public Starting Friday, February 23 at LiveNation.com LOS ANGELES, CA (February 20, 2018) – Today, multi-platinum artist Post Malone announced his upcoming North American tour with multi-platinum rapper 21 Savage and special guest SOB X RBE. Produced by Live Nation and sponsored by blu, the outing will kick off April 26 in Portland, OR and make stops in 28 cities across North America including Seattle, Nashville, Toronto, Atlanta, Austin, and more. The tour will wrap in San Francisco, CA on June 24. Tickets will go on sale to the general public starting Friday, February 23 at 10am local time at LiveNation.com. Citi® is the official presale credit card of the Post Malone tour. As such, Citi® cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning today, February 20th at 2pm local time until Thursday, February 22nd at 10pm local time through Citi’s Private Pass® program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Every pair of online tickets purchased comes with one physical copy of Post Malone’s forthcoming album, Beerbongs & Bentleys. Ticket purchasers will receive an additional email with instructions on how to redeem their album and will be notified at a later date on when they can expect to receive their CD. (U.S. and Canadian residents only.) The history-making Dallas, Texas artist, Post Malone, will also release his new single “Psycho” [feat. Ty Dolla $ign] on Friday February 23, 2018 via Republic Records. -

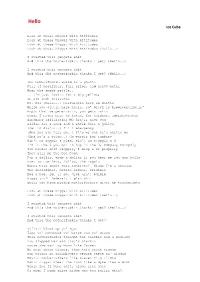

Ice Cube Hello

Hello Ice Cube Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} The motherfuckin world is a ghetto Full of magazines, full clips, and heavy metal When the smoke settle.. .. I'm just lookin for a big yellow; in six inch stilletos Dr. Dre {Hello..} perculatin keep em waitin While you sittin here hatin, yo' bitch is hyperventilatin' Hopin that we penetratin, you gets natin cause I never been to Satan, for hardcore administratin Gangbang affiliatin; MC Ren'll have you wildin off a zone and a whole half a gallon {Get to dialin..} 9 1 1 emergency {And you can tell em..} It's my son he's hurtin me {And he's a felon..} On parole for robbery Ain't no coppin a plea, ain't no stoppin a G I'm in the 6 you got to hop in the 3, company monopoly You handle shit sloppily I drop a ki properly They call me the Don Dada Pop a collar, drop a dollar if you hear me you can holla Even rottweilers, follow, the Impala Wanna talk about this concrete? Nigga I'm a scholar The incredible, hetero-sexual, credible Beg a hoe, let it go, dick ain't edible Nigga ain't federal, I plan shit while you hand picked motherfuckers givin up transcripts Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Booking Agency Info

Kristin Asbjørnsen www.kristinsong.com Singer and songwriter Kristin Asbjørnsen is one of the most distinguished artists on the vibrating extended music scene in Europe. During the last decade, she has received overwhelming international response among critics and public alike for her unique musical expression. 2018 saw the release of Kristin’s Traces Of You. Based on her assured melodic flair and poetic lyrics, Kristin has on this critically acclaimed album explored new fields of music. Vocals, kora and guitars are woven creatively into a meditative and warm vibration, showing traces of West African music, lullabyes and Nordic contemporary jazz. Lyrical African ornaments unite in a playful dialogue with a sonorous guitar universe. Kristin sings in moving chorus with the Gambian griot Suntou Susso, using excerpts of her poems translated into Mandinka language. During 2019 Kristin will be touring in Europe in trio with the kora player Suntou Susso and guitarist Olav Torget, performing songs from Traces Of You, as well as songs from her afro-american spirituals repertoire. Kristin is well known for her great live-performances and she is always touring with extraordinary musicians. The Norwegian singer has featured on a number of album releases, as well as a series of tours and festival performances in Europe. Her previous solo albums I’ll meet you in the morning (2013), The night shines like the day (2009) and Wayfaring stranger (2006) were released across Europe via Emarcy/Universal. Wayfaring stranger sold to Platinum in Norway. Kristin made the score for the movie Factotum (Bukowski/Bent Hamer) in 2005. Kristin collaborates with the jazz pianist Tord Gustavsen (ECM). -

Chance the Rapper Coloring Book Mp3, Flac, Wma

Chance The Rapper Coloring Book mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Coloring Book Country: US Released: 2016 MP3 version RAR size: 1582 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1475 mb WMA version RAR size: 1170 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 177 Other Formats: XM ADX MPC AC3 VQF ASF DMF Tracklist Hide Credits All We Got 1 Featuring – Chicago Children's Choir, Kanye WestProducer [Uncredited] – Kanye West, The 3:23 Social Experiment No Problem 2 5:04 Featuring – 2 Chainz, Lil WayneProducer [Uncredited] – Brasstracks Summer Friends 3 4:50 Featuring – Francis & The Lights*, Jeremih D.R.A.M. Sings Special 4 1:41 Featuring [Uncredited] – D.R.A.M. 5 Blessings 3:41 6 Same Drugs 4:17 Mixtape 7 4:52 Featuring – Lil Yachty, Young Thug Angels 8 3:26 Featuring – Saba Juke Jam 9 3:39 Featuring – Justin Bieber, Towkio All Night 10 2:21 Featuring – Knox Fortune How Great 11 5:37 Featuring – Jay Electronica, My Cousin Nicole Smoke Break 12 3:46 Featuring – Future Finish Line / Drown 13 6:46 Featuring – Eryn Allen Kane, Kirk Franklin, Noname , T-Pain Blessings (Reprise) 14 3:50 Featuring – Ty Dolla $ign* Credits Artwork [Uncredited] – Brandon Breaux Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Not On Label (Chance Chance The Coloring Book (14xFile, none The Rapper Self- none US 2016 Rapper MP3, Mixtape, 320) released) Coloring Book (2xLP, Chance The Not On Label (Chance CTRCB 3 Album, Mixtape, CTRCB 3 2016 Rapper The Rapper) Unofficial, Yel) Coloring Book (2xLP, Chance The Not On Label (Chance CTRCB3 Album, Mixtape, CTRCB3 2016 Rapper The Rapper) Unofficial, Cle) Chance The Coloring Book (2xLP, Not On Label (Chance none none UK 2018 Rapper Mixtape, Red) The Rapper) Coloring Book (2xLP, Chance The Not On Label (Chance none Mixtape, Unofficial, none US 2016 Rapper The Rapper) Gre) Related Music albums to Coloring Book by Chance The Rapper Rick Ro$$ - The Black Bar Mitzvah DJ UE - Monthly Whizz Vol. -

Hood, My Street: Ghetto Spaces in American Hip-Hop Music

Pobrane z czasopisma New Horizons in English Studies http://newhorizons.umcs.pl Data: 22/08/2019 20:22:20 New Horizons in English Studies 2/2017 CULTURE & MEDIA • Lidia Kniaź Maria Curie-SkłodowSka univerSity (uMCS) in LubLin [email protected] My City, My ‘Hood, My Street: Ghetto Spaces in American Hip-Hop Music Abstract: As a subculture created by black and Latino men and women in the late 1970s in the United States, hip-hop from the very beginning was closely related to urban environment. Undoubtedly, space has various functions in hip-hop music, among which its potential to express the group identity seems to be of the utmost importance. The goal of this paper is to examine selected rap lyrics which are rooted in the urban landscape: “N.Y. State of Mind” by Nas, “H.O.O.D” by Masta Ace, and “Street Struck,” in order to elaborate on the significance of space in hip-hop music. Interestingly, spaces such as the city as a whole, a neighborhood, and a particular street or even block which are referred to in the rap lyrics mentioned above express oneUMCS and the same broader category of urban environment, thus, words con- nected to urban spaces are often employed interchangeably. Keywords: hip-hop, space, urbanscape. Music has always been deeply rooted in everyday life of African American commu- nities, and from the very beginning it has been connected with certain spaces. If one takes into account slave songs chanted in the fields (often considered the first examples of rapping), or Jazz Era during which most blacks no longer worked on the plantations but in big cities, it seems that music and place were not only inseparable but also nat- urally harmonized.