Causal Effects of Violent Sports Video Games on Aggression: Is It Competitiveness Or Violent Content?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concord Mcnair Scholars Research Journal

Concord McNair Scholars Research Journal Volume 9 (2006) Table of Contents Kira Bailey Mentor: Rodney Klein, Ph.D. The Effects of Violence and Competition in Sports Video Games on Aggressive Thoughts, Feelings, and Physiological Arousal Laura Canton Mentor: Tom Ford, Ph.D. The Use of Benthic Macroinvertebrates to Assess Water Quality in an Urban WV Stream Patience Hall Mentor: Tesfaye Belay, Ph.D. Gene Expression Profiles of Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) 2 and 4 during Chlamydia Infection in a Mouse Stress Model Amanda Lawrence Mentor: Tom Ford, Ph.D. Fecal Coliforms in Brush Creek Nicholas Massey Mentor: Robert Rhodes Appalachian Health Behaviors Chivon N. Perry Mentor: David Matchen, Ph.D. Stratigraphy of the Avis Limestone Jessica Puckett Mentors: Darla Wise, Ph.D. and Darrell Crick, Ph.D. Screening of Sorrel (Oxalis spp.) for Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity Sandra L. Rodgers Mentor: Jack Sheffler, M.F.A. Rembrandt’s Path to Master Painter Crystal Warner Mentor: Roy Ramthun, Ph.D. Social Impacts of Housing Development at the New River Gorge National River 2 Ashley L. Williams Mentor: Lethea Smith, M.Ed. Appalachian Females: Catalysts to Obtaining Doctorate Degrees Michelle (Shelley) Drake Mentor: Darrell Crick, Ph.D. Bioactivity of Extracts Prepared from Hieracium venosum 3 Running head: SPORTS VIDEO GAMES The Effects of Violence and Competition in Sports Video Games on Aggressive Thoughts, Feelings, and Physiological Arousal Kira Bailey Concord University Abstract Research over the past few decades has indicated that violent media, including video games, increase aggression (Anderson, 2004). The current study was investigating the effects that violent content and competitive scenarios in video games have on aggressive thought, feelings, and level of arousal in male college students. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Moral Disengagement Strategies in Videogame Players and Sports Players

International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning Volume 8 • Issue 4 • October-December 2018 Moral Disengagement Strategies in Videogame Players and Sports Players Lavinia McLean, Technological University Dublin, Dublin, Ireland Mark D. Griffiths, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8880-6524 ABSTRACT Researchintheareaofvideogameplayandsportspsychologyhassuggestedthat specificstrategiesareoftenemployedbyplayerstojustifyaggressivebehaviourused duringgameplay.Thepresentstudyinvestigatestherelationshipbetweengameplayand moraldisengagementstrategiesinagroupof605adultswhoplayedviolentvideogames orregularlyplayedcompetitivesports.Theresultssuggestthatsportsplayerswere morelikelythanviolentgameplayerstoendorsemoraldisengagementstrategies.The videogamersweremorelikelytouseaspecificsetofmoraldisengagementstrategies i.e.,cognitiverestructuring)thantheothergroupsandthismayberelatedtothe) structuralcharacteristicsofvideogames.Thefindingsaddtorecentresearchexploring themechanismsbywhichindividualsengageinaggressiveactsbothvirtuallyandin real-lifesituations.Theresultsarediscussedinrelationtosimilarrelevantresearch .inthearea,alongwithrecommendationsforfutureresearch Keywords Aggression, Competitive Sports, Moral Disengagement, Sports, Video Game Play INTRoDUCTIoN Therehasbeenmuchresearchexploringtheimpactofviolentcontentinvideogames ,onyoungpeopleintermsofaggressivecognition,behaviour,andaffect(forreviews -

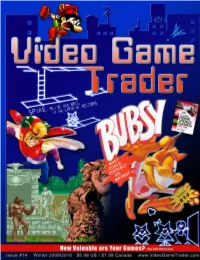

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Dreamcast USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Re R1 Dinosaur (Disney's)/Ubi Soft R4 Kao The Kangaroo/Titus R4 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker R1 Donald Duck Goin' Quackers (Disn R2 King of Fighters Dream Match, The R3 4 Wheel Thunder/Midway R2 Draconus: Cult of the Wyrm/Crave R2 King of Fighters Evolution, The/Ag R3 4x4 Evolution/GOD R2 Dragon Riders: Chronicles of Pern/ R4 KISS Psycho Circus: The Nightmar R1 AeroWings/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 01/Sega R0 Last Blade 2, The: Heart of the Sa R3 AeroWings 2: Airstrike/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 02/Sega R0 Looney Toons Space Race/Infogra R2 Air Force Delta/Konami R2 Ducati World Racing Challenge/Acc R4 MagForce Racing/Crave R2 Alien Front Online/Sega R2 Dynamite Cop/Sega R1 Magical Racing Tour (Walt Disney R2 Alone In The Dark: The New Night R2 Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the R2 Maken X/Sega R1 Armada/Metro3D R2 ECW Anarchy Rulez!/Acclaim R2 Mars Matrix/Capcom R3 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes/Midway R2 ECW Hardcore Revolution/Acclaim R1 Marvel vs. Capcom/Capcom R2 Atari Anniversary Edition/Infogram R2 Elemental Gimmick Gear/Vatical R1 Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of R2 Bang! Gunship Elite/RedStorm R3 ESPN International Track and Field R3 Mat Hoffman's Pro BMX/Activision R4 Bangai-o/Crave R4 ESPN NBA 2 Night/Konami R2 Max Steel/Mattel Interact R2 bleemcast! Gran Turismo 2/bleem R3 Evil Dead: Hail to the King/T*HQ R3 Maximum Pool (Sierra Sports)/Sier R2 bleemcast! Metal Gear Solid/bleem R2 Evolution 2: Far -

![[Catalog PDF] Manual Line Changes Nhl 14](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8833/catalog-pdf-manual-line-changes-nhl-14-888833.webp)

[Catalog PDF] Manual Line Changes Nhl 14

Manual Line Changes Nhl 14 Ps3 Download Manual Line Changes Nhl 14 Ps3 NHL 14 [PS3] - PS3. Trainers, astuces, triches et solutions pour Jeux PC, consoles et smartphones. Unlock the highest level of hockey aggression, speed and skill. NHL 14 brings together the best technology from EA SPORTS to deliver the most authentic hockey experience ever. Deliver hits with the cutting-edge NHL Collision Physics, built from FIFA's. NHL 14 for the Sony Playstation 3. Used game in great condition with a 90-day guarantee. DailyFaceoff line combinations - team lineups including power play lines and injuries are updated before and after game days based on real news delivered by team sources and beat reporters. Automated line changes based on calculations do not give you the team’s current lines – and that’s what you need for your fantasy lineups. EA Sports has announced that details of NHL 14 will be unveiled. Seeing as I have NHL 13 I can't imagine wanting to buy NHL 14 - but it'll be. In North America and on Wednesday in Europe (both XBox and PS3). It doesn't help that there's nothing in the manual to explain how to carry out faceoffs. Auto line changes and the idiot assistant coach. This problem seems to date back to time immemorial. Let’s say you have a bona fide top line center, rated at 87. Your second line center is an 82. Your third line center is an 80, and your fourth is a 75. NHL 14 PS3 Cheats. Gamerevolution Monday, September 16, 2013. -

Download Catalog

PHOTO SHOP 1. HIGH DEFINITION PHOTOS Our hi-tech superimposing system enables you and your guest to be put into over 100 different scenes and Magazine Covers. Items available: Lucite Frames, T-Shirts, Mouse pads, CD Jewel Cases, Mugs, Candy & Cereal Boxes, Snow Globes, Key Chains, OurMagnets, hi- Address Books, Compacts, Flashlights , Teddy Bears, Bobble Heads and more. 2. OLD FASHIONED PHOTOS Dress up in costumes from the late 1800’s and receive authentic looking tint type photos, complete with antique matte frames. 3. SPORTS CARD PHOTOS Authentic looking Baseball, Football, Hockey and Basketball cards; complete with 3D base that holds the Lucite protected card. 4. PHOTO SLIDE VIEWERS Our photographers take photos throughout the event. Each person that has their picture taken is handed a card with a number on it, the number will coincide with their viewer which is picked up at the end of the event. Viewers come in assorted colors w/ imprint in Black, Silver or Gold. 5. BLACK & WHITE/COLOR PHOTO STRIP BOOTH Old fashioned style picture booth, where guests go in and receive a Black & White or color strip that has 4 different poses. - 2 - 6. PHOTO SKETCH MACHINE Create your own hand-sketched portrait. Sit in our Sketch Booth and the computer sketches your exact likeness. Caricature style or regular, it will be the talk of the party. 8 x 10 photos. 7. DIGITAL PHOTO LOUNGE The latest craze in digital photography! Clear and vibrant prints are placed in a personalized frame. These photos are truly life-like and vivid, utilizing the latest digital technology. -

How the Video Game Industry Violates College Athletes' Rights of Publicity by Not Paying for Their Likenesses

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 21 Number 2 Article 1 1-1-2001 Gettin' Played: How the Video Game Industry Violates College Athletes' Rights of Publicity by Not Paying for Their Likenesses Matthew G. Matzkin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Matthew G. Matzkin, Gettin' Played: How the Video Game Industry Violates College Athletes' Rights of Publicity by Not Paying for Their Likenesses, 21 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 227 (2001). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol21/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GETTIN' PLAYED: HOW THE VIDEO GAME INDUSTRY VIOLATES COLLEGE ATHLETES' RIGHTS OF PUBLICITY BY NOT PAYING FOR THEIR LIKENESSES Matthew G. Matzkin* I. INTRODUCTION Envision all of the action and spirit of college athletics completely packaged and available on demand. For many fans, this dream is realized annually when video game producers release the latest college sports video game titles. Not surprisingly, producing these games is a lucrative enterprise, particularly as the games' graphics, sound and playability continue to improve with advances in technology.' The combination of video games and college sports translates into revenue for both video game producers and the collegiate institutions licensing their names and logos.2 However, the video game industry relies * B.A., University of California San Diego 1997; J.D., University of Southern California, 2000. -

ISSUE #163 February 2021 February CONTENTS 2021 163

The VOICE of the FAMILY in GAMING TM Final Fantasy XVI, Monster Hunter Rise, Slide Stars, and more this is- sue. Survey Says: “Fam- ily Feud Video Game for Fami- lies!” ISSUE #163 February 2021 February CONTENTS 2021 163 Links: Home Page Section Page(s) Editor’s Desk 4 Female Side 5 Comics 7 Sound Off 8 - 10 Look Back 12 Quiz 13 Devotional 14 In The News 16 - 23 We Would Play That! 24 Reviews 25 - 37 Sports 38 - 41 Developing Games 42 - 67 Now Playing 68 - 83 Last Minute Tidbits 84 - 106 “Family Friendly Gaming” is trademarked. Contents of Family Friendly Gaming is the copyright of Paul Bury, and Yolanda Bury with the exception of trademarks and related indicia (example Digital Praise); which are prop- erty of their individual owners. Use of anything in Family Friendly Gaming that Paul and Yolanda Bury claims copyright to is a violation of federal copyright law. Contact the editor at the business address of: Family Friendly Gaming 7910 Autumn Creek Drive Cordova, TN 38018 [email protected] Trademark Notice Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft all have trademarks on their respective machines, and games. The current seal of approval, and boy/girl pics were drawn by Elijah Hughes thanks to a wonderful donation from Tim Emmerich. Peter and Noah are inspiration to their parents. Family Friendly Gaming Page 2 Page 3 Family Friendly Gaming Editor’s Desk FEMALE SIDE million that got infected with it. That was one propaganda artist trying to do damage con- Ups and Downs third of the human population at the time. -

Titre Dreamcast Pal Jeu Boite Notice Autres

TITRE DREAMCAST PAL JEU BOITE NOTICE AUTRES 102 Dalmatiens : Puppies to the Rescue 18 Wheeler American Pro Trucker 4 VVheel Thunder 90 Minutes Aero Wings Aero Wings 2 : Air Strike Alone in the Dark: The New Nightmare Aqua GT Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Bangai-O Blue Stinger Buggy Heat Bust a Move 4 Buzz Lightyear of Star Command Caesars Palace 2000 Cannon Spike Capcom vs. SNK Carrier Championship Surfer Charge 'N' Blast Chicken Run Chu Chu Rocket! Coaster Works Confidential Mission Conflict Zone Crazy Taxi Crazy Taxi 2 Dave Mirra Freestyle BMX Daytona USA 2001 Dead or Alive 2 Deadly Skies Deep Fighter Dino Crisis Disney's Dinosaur Donald Duck : Couak Attack Dragon Riders : Chronicles of Pern Dragon's Blood Ducati World Dynamite Cop Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the Future ECW Anarchy ECW Hardcore Revolution European Super League Evil Dead: Hail to the King Evil Twin Cyprien's Chronicles Evolution : The World of Sacred Devices Evolution 2 : Far off Promise Exhibition of Speed F1 Racing Championship F1 World Grand Prix F1 World Grand Prix 2 Ferrari 355 Challenge : Passione Rossa Fighting Force 2 Fighting Vipers 2 Floigan Brothers : Episode One Freestyle Scooter Fur Fighters Gauntlet Legends Giant Killers Giga Wing Grand Theft Auto 2 Grandia 2 Grinch, The Gunbird 2 Headhunter Heavy Metal Geomatrix Hidden and Dangerous House of the Dead 2, The Hydro Thunder Incoming International Track and Field Iron Aces Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 Jet Set Radio Jimmy White 2 : Cueball Jo Jo Bizarre Adventure Kao the Kangaroo Kiss Psycho Circus : The Nightmare -

000NAG Xbox Insider November 2006

Free NAG supplement (not to be sold separately) THE ONLY RESOURCE YOU’LL NEED FOR EVERYTHING XBOX 360 November 2006 Issue 2 THE SPIRIT OF SYSTEM SHOCK THE NEW ERA VENUS RISES OVER GAMING INSIDE! 360 SOUTH AFRICA RAGE LAUNCH EVERYTHING X06 TONY HAWK’S PROJECT 8 DASHBOARD WHAT’S IN THE BOX? 8 THE BUZZ: News and 360 views from around the planet 10 FEATURE: Local Launch We went, we stood in line, we watched people pick up their preorders. South Africa just got a little greener 12 FEATURE: The New Era As graphics improve, as gameplay evolves, naturally it is only a matter of time before seperation between male and female gamers dissolves 20 PREVIEW: Bioshock It is System Shock 3 in everything but the name. And it lacks Shodan. But it is still very System Shock, so much so that we call it BioSystemShock 28 FEATURE: Project 8 Mr. Hawk returns and this time he’s left the zany hijinks of Bam Magera behind. Project 8 is all about the motion, expression and momentum 29 HARDWARE: Madcatz offers up some gamepad and HD VGA cable love, and the gamepad can be used on the PC too! 36 OPINION: The Class of 360 This month James Francis reminds us why we bought a PlayStation 2 in the first place, and then calls us fanboys 4 11.2006 EDITOR SPEAK AND HE SAID, “LET THERE BE RING OF LIGHT” publisher tide media managing editor michael james [email protected] +27 83 409 8220 editor miktar dracon [email protected] assistant editor lauren das neves [email protected] copy editor nati de jager contributors matt handrahan james francis ryan king jon denton group sales and marketing manager len nery | [email protected] +27 84 594 9909 advertising sales jacqui jacobs | [email protected] +27 82 778 8439 t was nothing short of incredible to see so dave gore | [email protected] +27 82 829 1392 cheryl bassett | [email protected] much enthusiasm and support for the Xbox +27 72 322 9875 art director 360, as was seen at both rAge and at the BT chris bistline I designer Games Xbox 360 launch party.