My Ancestors Who Were Sureties of the Magna Carta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magna Carta and the Development of the Common Law

Magna Carta and the Development of the Common Law Professor Paul Brand, FBA Emeritus Fellow All Souls College, Oxford Paper related to a presentation given for the High Court Public Lecture series, at the High Court of Australia, Canberra, Courtroom 1, 13 May 2015 Magna Carta and the Development of the Common Law I We are about to commemorate the eight hundredth anniversary of the granting by King John on 15 June 1215 of a ‘charter of liberties’ in favour of all the free men of his kingdom [of England] and their heirs. That charter was not initially called Magna Carta (or ‘the Great Charter’, in English). It only acquired that name after it had been revised and reissued twice and after the second reissue had been accompanied by the issuing of a separate, but related, Charter of the Forest. The revised version of 1217 was called ‘The Great Charter’ simply to distinguish it from the shorter, and therefore smaller, Forest Charter, but the name stuck. To call it a ‘charter of liberties’ granted by king John to ‘all the free men of his kingdom’ of England is, however, in certain respects misleading. The term ‘liberty’ or ‘liberties’, particularly in the context of a royal grant, did not in 1215 bear the modern meaning of a recognised human right or human rights. ‘Liberty’ in the singular could mean something closer to that, in the general sense of the ‘freedom’ or the ‘free status’ of a free man, as opposed to the ‘unfreedom’ of a villein. ‘Liberties’, though, were something different (otherwise known as ‘franchises’), generally specific privileges granted by the king, particular rights such as the right to hold a fair or a market or a particular kind of private court, the right to have a park or a rabbit warren which excluded others from hunting or an exemption such as freedom from tolls at markets or fairs. -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Signers of the Magna Carta the King and 25 Surety Barons King John

Signers of the Magna Carta The King and 25 Surety Barons King John Plantagenet (Relative) William d'Albini, Lord of Belvoir Castle. Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk. (Relative) Hugh Bigod, Heir to the Earldoms of Norfolk and Suffolk. (Relative) Henry de Bohun, Earl of Hereford. (Relative) Richard de Clare, Earl of Hertford. (Relative) Gilbert de Clare, Heir to the Earldom of Hertford. (Relative) John FitzRobert, Lord of Warkworth Castle. Robert FitzWalter, Lord of Dunmow Castle. William de Fortibus, Earl of Albemarle. William Hardell, Mayor of the City of London. William de Huntingfield, Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk. John de Lacie, Lord of Pontefract Castle. William de Lanvallei, Lord of Standway Castle. William Malet, Sheriff of Somerset and Dorset. Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex and Gloucester. William Marshall jr, Heir to the Earldom of Pembroke. (Relative) Roger de Montbegon, Lord of Hornby Castle. Richard de Montfichet, Baron. William de Mowbray, Lord of Axholme Castle. Richard de Percy, Baron. Saire de Quincey, Earl of Winchester. (Relative) Robert de Roos, Lord of Hamlake Castle. Geoffrey de Saye, Baron. Robert de Vere, Heir to the Earldom of Oxford. Eustace de Vesci, Lord of Alnwick Castle. In 1215 the Magna Carta, also known as the Great Charter, was signed at Runnymede in Egham, Surrey, South England by King John. The Magna Carta was an attempt to limit the King's powers. "Magna Carta" is Latin and means "Great Charter". The document was a series of written promises between the king and his subjects that he, the king, would govern England and deal with its people according to the customs of feudal law. -

William Marshal and Isabel De Clare

The Marshals and Ireland © Catherine A. Armstrong June 2007 1 The Marshals and Ireland In the fall of 1947 H. G. Leaske discovered a slab in the graveyard of the church of St. Mary‟s in New Ross during the repair works to the church (“A Cenotaph of Strongbow‟s Daughter at New Ross” 65). The slab was some eight feet by one foot and bore an incomplete inscription, Isabel Laegn. Since the only Isabel of Leinster was Isabel de Clare, daughter of Richard Strongbow de Clare and Eve MacMurchada, it must be the cenotaph of Isabel wife of William Marshal, earl of Pembroke. Leaske posits the theory that this may not be simply a commemorative marker; he suggests that this cenotaph from St Mary‟s might contain the heart of Isabel de Clare. Though Isabel died in England March 9, 1220, she may have asked that her heart be brought home to Ireland and be buried in the church which was founded by Isabel and her husband (“A Cenotaph of Strongbow‟s Daughter at New Ross” 65, 67, 67 f 7). It would seem right and proper that Isabel de Clare brought her life full circle and that the heart of this beautiful lady should rest in the land of her birth. More than eight hundred years ago Isabel de Clare was born in the lordship of Leinster in Ireland. By a quirk of fate or destiny‟s hand, she would become a pivotal figure in the medieval history of Ireland, England, Wales, and Normandy. Isabel was born between the years of 1171 and 1175; she was the daughter and sole heir of Richard Strongbow de Clare and Eve MacMurchada. -

Corrections to Domesday Descendants As Discussed by the Society/Genealogy/Medieval Newsgroup

DOMESDAY DESCENDANTS SOME CORRIGENDA By K. S. B. KEATS-ROHAN Bigod, Willelm and Bigod comes, Hugo were full brothers. Delete ‘half-brother’. de Brisete, Jordan Son of Ralph fitz Brien, a Domesday tenant of the bishop of London. He founded priories of St John and St Mary at Clerkenwell during the reign of Stephen. He married Muriel de Munteni, by whom he had four daughters, Lecia wife of Henry Foliot, Emma wife of Rainald of Ginges, Matilda, a nun of Clerkenwell, and Roesia. After his death c. 1150 his widow married secondly Maurice son of Robert of Totham (q.v.). Pamela Taylor, ‘Clerkenwell and the Religious Foundations of Jordan de Bricett: A Re-examination’, Historical Research 63 (1990). de Gorham, Gaufrid Geoffrey de Gorham held, with Agnes de Montpincon or her son Ralph, one fee of St Albans abbey in 1166. Kinsman of abbots Geoffrey and Robert de Gorron. Abbot Geoffrey de Goron of St Albans built a hall at Westwick for his brother-in-law Hugh fitz Humbold, whose successors Ivo and Geoffrey used the name de Gorham (GASA i, p. 95). Geoffrey brother of Abbot Robert and Henry son of Geoffrey de Goram attested a charter of Archdeacon John of Durham c. 1163/6 (Kemp, Archidiaconal Acta, 31). Geoffrey’s successor Henry de Gorhan of Westwick (now Gorhambury) held in 1210 (RBE 558). VCH ii, 393. de Mandeville, Willelm Son of Geoffrey I de Mandeville of Pleshy, Essex, whom he succeeded c. 1100. He also succeeded his father as constable of the Tower of London, and office that led to his undoing when Ranulf, bishop of Durham, escaped from his custody in 1101. -

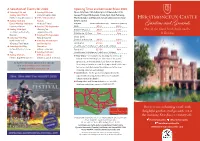

Gardens and Grounds

A Selection of Events for 2020 Opening Times and Admission Prices 2020 u Saturday 21st and u Sunday 28th June Open daily from 15th February to 1st November 2020 Sunday 22nd March Canadian Connections (except Friday 28th August), 10am–6pm (5pm February, Mother’s Day Afternoon Tea u 29th, 30th and 31st March, October and November). Last admission one hour u Sunday 12th and August before closing. Easter Monday 13th April Medieval Festival Daily Rate Gardens and Grounds only Castle Tours (extra fee) Gardens and Grounds Easter Family Fun u Sunday 13th September Adult £7.00 £3.00 u Sunday 26th April Wedding Fair Child (4–17 years) £3.50 £1.50 One of the finest brick built castles Tea Dance in the Castle (Empirical Events) Child (under 4), Carer Free Free in Britain Ballroom u Sunday 27th September u Saturday 16th May Taste of Autumn Senior (65+), Castle Night Trek u Saturday 31st October Disabled and Student £6.00 £3.00 (Chestnut Tree House) and Sunday 1st Family of 4 £17.50 N/A u Saturday 23rd May November (2 adults and 2 children or 1 adult and 3 children) National Garden Scheme Halloween Horrors Family of 5 £21.50 N/A Day u Sundays 13th and (2 adults and 3 children or 1 adult and 4 children) u Sunday 21st June 20th December u Tour times – are available by checking the website or Father’s Day Afternoon Tea Christmas Lunch and Carols calling 01323 833816 (please note that as the Castle operates as an International Study Centre for Queen’s For further information and full events calendar University in Canada, it is not freely open to the public and visit www.herstmonceux-castle.com tours are scheduled around timetables and other uses or email [email protected] including conferences/weddings). -

THE LEGACY of the MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 the Magna Carta Controlled the Power Government Ruled with the Consent of Eventually Spreading Around the Globe

THE LEGACY OF THE MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 The Magna Carta controlled the power government ruled with the consent of eventually spreading around the globe. of the King for the first time in English the people. The Magna Carta was only Reissues of the Magna Carta reminded history. It began the tradition of respect valid for three months before it was people of the rights and freedoms it gave for the law, limits on government annulled, but the tradition it began them. Its inclusion in the statute books power, and a social contract where the has lived on in English law and society, meant every British lawyer studied it. PETITION OF RIGHT 1628 Sir Edward Coke drafted a document King Charles I was not persuaded by By creating the Petition of Right which harked back to the Magna Carta the Petition and continued to abuse Parliament worked together to and aimed to prevent royal interference his power. This led to a civil war, and challenge the King. The English Bill with individual rights and freedoms. the King ultimately lost power, and his of Rights and the Constitution of the Though passed by the Parliament, head! United States were influenced by it. HABEAS CORPUS ACT 1679 The writ of Habeas Corpus gives imprisonment. In 1697 the House of Habeas Corpus is a writ that exists in a person who is imprisoned the Lords passed the Habeas Corpus Act. It many countries with common law opportunity to go before a court now applies to everyone everywhere in legal systems. and challenge the lawfulness of their the United Kingdom. -

Ubi Jus, Ibi Remedium: the Fundamental Right to a Remedy, 41 San Diego Law Review 1633 (2004)

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Publications The chooS l of Law January 2004 Ubi Jus, Ibi Remedium: The undF amental Right to a Remedy Tracy A. Thomas 1877, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/ua_law_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tracy A. Thomas, Ubi Jus, Ibi Remedium: The Fundamental Right to a Remedy, 41 San Diego Law Review 1633 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The chooS l of Law at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Publications by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Forthcoming, Symposium: Remedies Discussion Forum, 41 U.S.D. ___ (2004) Ubi Jus, Ibi Remedium: The Fundamental Right to a Remedy Under Due Process Tracy A. Thomas* One of the legacies of Brown v. Board of Education is its endorsement of affirmative remedial action to enforce constitutional rights.1 In Brown I and Brown II, the United States Supreme Court rejected mere declaratory or prohibitory relief in favor of a mandatory injunction that would compel the constitutionally-required change.2 Disputes over the parameters of this active remedial power and compliance with the ordered remedies have dominated the ensuing decades of post-Brown school desegregation cases.3 These enforcement disputes have overshadowed the importance of Brown’s establishment of a remedial norm embracing affirmative judicial action to provide meaningful relief. -

The Royal Prerogative and Equality Rights the Royal

THE ROYAL PREROGATIVE AND EQUALITY RIGHTS 625 THE ROYAL PREROGATIVE AND EQUALITY RIGHTS: CAN MEDIEVAL CLASSISM COEXIST WITH SECTION 15 OF THE CHARTER? GERALD CHI PE UR• The author considers whether the prerogative L' auteur se demande si la prerogative de priorite priority of the Crown in the collection of debts of de la Cour01me dans le recouvrement des crea11ces equal degree is inconsistem with the guaramee of de degre ega/ respecte la garantie d' egalite que equality found in section I 5 of the Canadian Charter colltiefll /' art. 15 de la Charle des droits et libertes. of Rights an.d Freedoms "Charter." He concludes Sa conclusion est negatfre et ii estime qu',me telle that the Crown prerogative of priority is 1101 prerogatfre ne constitue pas une limite raismmable consistent with section I 5 and that such prerogative dons ,me societe fibre et democratique, atLrtermes de is not a reasonable limit in a free and democratic /' art. I de la Charte. society under section 1 of the Charter. L' a111eur etudie d' abord /es origines de la The author first investigates the origins of the prerogative de la Courom1e,puis la prerogative de la Crown prerogative in general and then the priorite plus particulierement. II I' examine ensuite a prerogative of priority in particular. The author then la lumiere de la Chane. L' auteur dec:/areque /' objet proceeds to apply the Charter to the prerogative of de la prerogative de priorite etait de recom,aitre la priority. The author submits that the purpose of the notion medierale de preeminence et superiorite prerogative priority is to recogni:e the medieval person11elle de la Reine sur ses sujets, et qu'un tel concept of the personal pre-eminence and superiority objet est contraire aux valeurs promues par la of the Queen over her subjects and that such a garalltie d' egalite e11oncee dons I' art. -

Neighbourhood Plan (PDF)

Great Dunmow Neighbourhood Plan 2015-2032 1 | GDNP Great Dunmow Neighbourhood Plan 2015-2032 © Great Dunmow Town Council (GDTC) 2016 This Plan was produced by Great Dunmow Town Council through the office of the Town Clerk, Mrs. Caroline Fuller. It was overseen by the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group, chaired by Cllr. John Davey. Written and produced by Daniel Bacon. This document is also available on our website, www.greatdunmow-tc.gov.uk. Hard copies can be viewed by contacting GDTC or Uttlesford District Council. With thanks to the community of Great Dunmow, Planning Aid England, the Rural Community Council of Essex, Easton Planning, and Uttlesford District Council. The Steering Group consisted of: Cllr. John Davey (Chair) (GDTC & UDC), Cllr. Philip Milne (Mayor) (GDTC), Cllr. David Beedle (GDTC), Mr. William Chastell (Flitch Way Action Group), Mr. Tony Clarke, Cllr. Ron Clover (GDTC), Mr. Darren Dack (Atlantis Swimming Club), Mr. Norman Grieg (Parsonage Downs Conservation Society), Mr. Tony Harter, Cllr. Trudi Hughes (GDTC), Mr. Mike Perry (Chamber of Trade), Dr Tony Runacres, Mr. Christopher Turton (Town Team), Mr. Gary Warren (Dunmow Society). With thanks to: Rachel Hogger (Planning Aid), Benjamin Harvey (Planning Aid), Stella Scrivener (Planning Aid), Neil Blackshaw (Easton Planning), Andrew Taylor (UDC), Melanie Jones (UDC), Sarah Nicholas (UDC), Hannah Hayden (UDC), Jan Cole (RCCE), Michelle Gardner (RCCE). Maps (unless otherwise stated): Reproduced under licence from HM Stationary Office, Ordnance Survey Maps. Produced by Just Us Digital, Chelmsford Road Industrial Estate, Great Dunmow. 2 | GDNP Contents I. List of Figures 4 II. Foreword 5 III. Notes on Neighbourhood Planning 7 IV. -

Ancestors of Phillip Pasfield of Wethersfield, Essex, England

Ancestors of Phillip Pasfield of Wethersfield, Essex, England Phillip Pasfield was born in Wethersfield about 1615 and died in early 1685 in Wethersfield. He lived there his entire life, as did his ancestors going back at least 250 years. This paper will identify and document his known ancestors. Community of Wethersfield Wethersfield is now and always has been a very small community in northwest Essex County. Its history dates back to at least 1190.[1] The earliest known map dated in 1741 shows the roads that connect Wethersfield to other nearby towns and a number of small properties on either side of those roads.[2] Although there are very few Essex County records prior to 1600, Phillip’s ancestors can be traced through them back to the early 1400s in Wethersfield. The surviving parish records in Wethersfield begin about 1650. Fortunately there are wills from 1500 and some land and court records available from the 1300s in the Essex County archives. There are also lawsuits in London Chancery courts that help the genealogical researcher trace Phillip Pasfield and his ancestors. Wethersfield Land Records Land records in early Essex County typically assign names to the various properties rather than use metes and bounds or acres. The assigned property names come from various sources, including names of previous owners of the property. Land transactions typically list the sellers and the buyers, property name, and the neighboring land owners. Many of these properties are bought and sold by groups of individuals who may or may not all be relatives. Because of the lack of wills and available vital records, property ownership plays a critical role in tracing Phillip’s ancestors. -

A Vernacular Anglo-Norman Chronicle from Thirteenth- Century Ireland*

"GO WEST, YOUNG MAN!": A VERNACULAR ANGLO-NORMAN CHRONICLE FROM THIRTEENTH- CENTURY IRELAND* William Sayers The vernacular literary record of the Anglo-Norman invasion and settlement of twelfth- and thirteenth-century Ireland is a sparse one. Leaving to one side the native annals and the more indirect reflection of these events as a stimulus to the compilation of the great codices such as the Book of Leinster and the Book of the Dun Cow,^" only two documents are extant in the French language. One, little marked by Anglo-Norman dialect features, is a poem from 1265 commemorating the 2 completion of trench and bank fortifications at New Ross. The other, more substantial work is a chronicle of 3459 rhymed octosyllabic couplets in Anglo-Norman French, dated to 1225 or 1230; the single manuscript is incomplete at beginning and end. With the exception of the introductory episode, the body of the work commences with events in 1166, details the advent of the Cambro- Norman adventurers and the first imposition of English power in Ireland, and may well have ended with the death of a major figure in 1176. Although more restricted in temporal span and somewhat more in scope than Giraldus Cambrensis' Expugnatio hibernica, dating from 1188-89, it has served historians as a major source for this last surge of Norman expansionism. The manuscript was last edited in 1892 by Goddard H. Orpen as The Song of Dermot and the Earl and served as key evidence for much of his Ireland Under the Normans.^ In fact, M. Domenica Legge, in her authoritative 119 120 Anglo-Norman Literature and its Background, claims that "the editor had, 4 very naturally, an exaggerated idea of its historical value.