Halifax Regional Municipality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

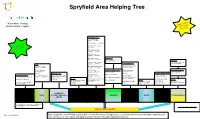

Spryfield Area Helping Tree

Spryfield Area Helping Tree lan Recreation Therapy e a p Mak w follo Mental Health Program and ugh! thro Spiritual Resources #9 Calvary United Baptist…..477-4099 #10 City Church …..479-2489 nd it! A #11 Emmanuel Anglican….. et F 477-1783 G Fun! ave H #12 Saint Augustine’s Anglican….. 477-5424 #13 Saint James Anglican…..477-2979 #14 Saint Joseph’s Indoor Pool Monastery…..477-3937 #20 Spryfield Lion’s Wave Pool…..477-POOL Gardening #15 Saint John The Baptist #32 Urban Farm Museum Catholic …...477-3110 Community Centres Society of Spryfield Yoga #25 Captain William Spry #4 Ready to Rumba #16 Saint Michael’s Roman Community Centre/wave Dance…..444-3129 Catholic …...477-3530 pool…..477-POOL #5 Chocolate Lake #17 Saint Paul’s Supervised Beaches (Free) #26 Chocolate Lake Halifax Public Libraries Recreation Centre….. United …...477-3937 #21 Kidston Lake Community Center…… #33 Captain William 490-4607 490-4607 Spry…..490-5818 Wellness Centre Senior’s Club and Centres #7 Chebucto Connections #18 Saint Phillips #22 Long Pond Beach #30 Spryfield Senior Free Walking Groups #6 Captain William Spry #27 Harrietsfield/ and Chebucto Community Anglican…..477-2979 Centre…..477-5658 #1 Heart and Stroke Walkabout Centre …..477-7665 Williamswood Community Wellness Centre ….. #23 Crystal Crescent Beach Skating #19 Salvation Army Spryfield Centre…...446-4847 #31 Golden Age Social #2 Chebucto Hiking Club 487-0690 Bowling #8 Spryfield Lions Rink and Community Church….. #24 Cunard Beach Dance Centre Society Recreation Centre….. 477-5393 #28 Spryfield Recreation #34 Spryfield #3 Visit one of the many trails #29 Ready to Rumba Young at Heart 477-5456 Centre Bowlarama…..479-2695 available in HRM Dance….444-3129 Club…..477- 3833 COMMUNITY FREE WALKING SPIRITUAL COMMUNITY SENIOR’S YOGA SUPPORT/ WELLNESS SKATING SWIMMING DANCE MISCELLANEOUS GROUPS RESOURCES CENTRES CENTRES GROUPS The Spryfield Area Helping Tree was adapted from the PEI Helping Tree. -

NS Public Libraries Annual Report

Nova Scotia’s Public Libraries: A Year in Review Nova Scotia 78 library 29,900 In the past year, regional libraries have achieved Public Libraries many milestones and offered many programs and branches new users services; below are just a few highlights: Annual Report across the province Annapolis Valley Regional Library A new multipurpose Sprinter Bookmobile now serves rural, outlying areas and institutions. It is great for 2013–2014 promoting library services at community events. Cape Breton Regional Library New projects and programs included additional Message from the Minister Message from the Director Babies & Books programs and, in conjunction with community partners, a digital project, “Through Her As the Minister of the Nova Working collaboratively Eyes: Katharine McLennan”. Scotia Department of with the public library Communities, Culture and community continues to Colchester-East Hants Public Library Heritage, I am pleased to be be central to the Provincial Honouring the past, building the future, municipal and library officials are renovating and expanding a steward of our public Library mission as we the 19th century, former Normal College to libraries. coordinate and deliver become the region’s central library. multiple services and Our libraries are excellent programs to Nova Scotia Cumberland Public Libraries examples of collaborative community spaces public libraries. We worked with the Council Throughout the year the region began offering that support life-long learning and literacy. They of Regional Librarians on the development programs for all ages, at all locations, and saw a have proven to be important gathering places for of a core services document for NS public 20% increase in program attendance. -

Download Download

Evidence Based Library and Information Practice 2010, 5.2 Evidence Based Library and Information Practice Article The Life of the Space: Evidence from Nova Scotia Public Libraries Francine May Assistant Professor Mount Royal University Calgary, Alberta, Canada [email protected] Fiona Black Associate Professor / Director, School of Information Management Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada [email protected] Received: 5 Aug. 2009 Accepted: 12 April 2010 2010 May and Black. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐ Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‐nc‐ sa/2.5/ca/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one. Abstract Objectives – To describe aspects of the 21st century role of the public library as a physical space by observing the actual use of a selection of public libraries. This study seeks to reveal how patrons are using and experiencing these institutions as spaces and how patrons and staff characterize the role of public libraries in communities. Methods – A multiple case study design was used to examine three urban and three small town public libraries within Nova Scotia, Canada. A triangulated set of methods including patron interviews and questionnaires, staff interviews, and seating sweeps was used to develop answers to the research questions. Results – These public libraries are functioning as successful public places in that they are community spaces used in a multitude of ways and where patrons feel welcome. -

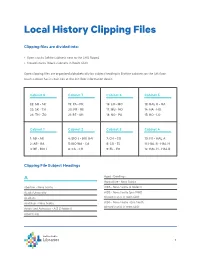

Local History Clipping Files

Local History Clipping Files Clipping files are divided into: • Open stacks (white cabinets next to the LHG Room) • Closed stacks (black cabinets in Room 440) Open clipping files are organized alphabetically by subject heading in 8 white cabinets on the 4th floor (each cabinet has its own key at the 4th floor information desk): Cabinet 8 Cabinet 7 Cabinet 6 Cabinet 5 22: SH - SK 19: PA - PR 16: LO - MO 13: HAL R - HA 23: SK - TH 20: PR - RE 17: MU - NO 14: HA - HO 24: TH - ZO 21: RE - SH 18: NO - PA 15: HO - LO Cabinet 1 Cabinet 2 Cabinet 3 Cabinet 4 1: AB - AR 4: BIO J - BIO U-V 7: CH - CO 10: FO - HAL A 2: AR - BA 5: BIO WA - CA 8: CO - EL 11: HAL B - HAL H 3: BE - BIO I 6: CA - CH 9: EL - FO 12: HAL H - HAL R Clipping File Subject Headings A Aged - Dwellings Agriculture - Nova Scotia Abortion - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia (2 folders) Acadia University AIDS - Nova Scotia (pre-1990) Acadians (closed stacks in room 440) Acid Rain - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia - Eric Smith (closed stacks in room 440) Actors and Actresses - A-Z (3 folders) Advertising 1 Airlines Atlantic Institute of Education Airlines - Eastern Provincial Airways (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Atlantic School of Theology Airplane Industry Atlantic Winter Fair (closed stacks in room 440) Airplanes Automobile Industry and Trade - Bricklin Canada Ltd. Airports (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Algae (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Canadian Motor Ambulances Industries (closed stacks in room 440) Amusement Parks (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Lada (closed stacks in room 440) Animals Automobile Industry and Trade - Nova Scotia Animals, Treatment of Automobile Industry and Trade - Volvo (Canada) Ltd. -

Request to Include 5381 Spring Garden Road, Halifax in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 15.3.1 Halifax Regional Council December 10, 2019 TO: Mayor Mike Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council Original Signed SUBMITTED BY: For Jenny Lugar, Chair, Heritage Advisory Committee DATE: November 28, 2019 SUBJECT: Case H00469: Request to Include 5381 Spring Garden Road, Halifax in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality ORIGIN • A third-party application for registration under the Heritage Property Act. • November 27, 2019 meeting of the Heritage Advisory Committee, Item 9.1.1. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Heritage Property Act s. 14(1) A heritage advisory committee may recommend to the municipality that a building, public building interior, streetscape, cultural landscape or area be registered as a municipal heritage property in the municipal registry of heritage property. HRM By-law No. H-200 - Heritage Property By-law 4. The [Heritage Advisory] Committee shall, within the time limits prescribed by Council or the [Heritage Property] Act, advise the Region respecting: (a) the inclusion of buildings, public building interiors, streetscapes, cultural landscapes or areas in the Registry. RECOMMENDATION The Heritage Advisory Committee recommends that Halifax Regional Council: 1. Set a date for a heritage hearing to consider the inclusion of the subject property in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality; and 2. Approve the request to include 5381 Spring Garden Road in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality, as shown on Map 1 of the September 9, 2019 staff report, as a municipal heritage area under the Heritage Property Act. -

Central Library Building Program and Space

HALIFAX CENTRAL LIBRARY Halifax, N.S. BUILDING PROGRAM AND SPACE REQUIREMENTS June 2008 HALIFAX CENTRAL LIBRARY Halifax, N.S. BUILDING PROGRAM AND SPACE REQUIREMENTS June 2008 The proposed future Central Library will blend the best of traditional library services with new and innovative spaces, making it a vital centre for learning and culture in the heart of the community. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY page iv 5. BUILDING PROGRAM AND SPACE REQUIREMENTS FOR CENTRAL LIBRARY page 21 1. INTRODUCTION page 01 5.1 General Library Guidelines page 21 1.1 Project Background page 01 5.2 Breakdown of Space Requirements page 22 1.2 Project Process page 02 5.3 Breakdown of Building Program and 1.3 Document Organization page 04 Proposed Adjacencies page 30 5.3.1 Lobby / Arrival page 30 2. VISION FOR THE HALIFAX CENTRAL LIBRARY page 05 5.3.2 Access Services / Book Circulation Services page 30 2.1 What is a Central Library? page 06 5.3.3 Public Computers page 30 2.2 Spring Garden Road Memorial Library Background page 06 5.3.4 Café page 30 2.3 Comparison of the Proposed Central Library to the 5.3.5 Adult Services page 31 Existing Spring Garden Memorial Library page 07 5.3.6 Local History / Genealogy page 32 2.4 Benefi ts of a Central Library page 08 5.3.7 Adult Learning Centre page 33 3. PUBLIC CONSULTATION PROCESS page 09 5.3.8 Centre for Technology Innovation page 34 3.1 Consultation Process page 09 5.3.9 Teen Services page 35 3.2 Phase One – February, 2008 page 09 5.3.10 Children’s Services page 36 3.3 Survey Results page 10 5.3.11 Program & Meeting Spaces page 37 3.4 Phase Two – April, 2008 page 10 5.3.12 Outdoor Space page 38 3.5 Development of Alternative Themes page 11 5.3.13 Universal Design page 38 3.5.1 Community Centre for Culture page 12 5.3.14 Public Restrooms page 38 3.5.2 Community Centre for Learning page 13 5.3.15 Regional Services page 38 3.5.3 Community Centre for Partnership page 14 5.3.16 Maintenance page 38 3.6 Phase Three – June, 2008 page 15 5.3.17 Staff Facilities page 39 5.3.18 General Storage page 39 4. -

Riders' Guide Contains Timetables for All Halifax Transit Routes in Numerical Order

RIDERS’ GUIDE Effective May 28, 2018 311 Departure Line: 902-480-8000 halifax.ca/transit Watch where it will take you. TRANSIT Routes The transit fleet is 100% accessible and equipped with bike racks. 1 Spring Garden page 5 2 Wedgewood 7 4 Rosedale 11 5 Chebucto 13 7 Robie 14 9 Herring Cove (REVISED) 18 10 Dalhousie 24 11 Dockyard 27 14 Leiblin Park 28 15 Purcells Cove 30 16 Parkland 31 17 Saint Mary's 32 18 Universities 33 21 Lakeside—Timberlea 35 22 Armdale 36 23 Timberlea—Mumford 38 29 Barrington 39 31 Main Express 43 32 Cowie Hill Express 44 33 Tantallon Express 44 34 Glenbourne Express 45 35 Parkland Express 45 41 Dartmouth—Dalhousie 46 42 Lacewood—Dalhousie 46 51 Windmill 47 52 Crosstown 48 53 Notting Park 52 54 Montebello 53 55 Port Wallace 54 56 Dartmouth Crossing 55 57 Russell Lake 56 58 Woodlawn 57 59 Colby 58 60 Eastern Passage—Heritage Hills 60 61 Auburn—North Preston 64 62 Wildwood 68 63 Woodside 70 64 Akerley 71 65 Caldwell 71 66 Penhorn 72 68 Cherry Brook 74 72 Portland Hills 76 78 Mount Edward Express 77 79 Cole Harbour Express 77 80 Sackville 78 81 Hemlock Ravine 82 82 Millwood 83 83 Springfield 85 84 Glendale Express 86 85 Downsview Express 86 86 Basinview Express 87 87 Glendale 88 88 Bedford Commons 89 89 Bedford 90 90 Larry Uteck (REVISED) 91 159 Portland Hills Link 92 185 Sackville Link 93 194 West Bedford Express 94 320 Airport—Fall River MetroX (REVISED) 95 330 Tantallon—Sheldrake Lake Regional Express 96 370 Porters Lake Regional Express 96 400 Beaver Bank 97 401 Preston—Porters Lake—Grand Desert 98 Ferry Alderney Ferry and Woodside Ferry 99 2 Understanding the Route Schedules This Riders' Guide contains timetables for all Halifax Transit routes in numerical order. -

Budget & Business Plans

BUDGET & BUSINESS 2020 - 2021 PLANS Pre-COVID-19 TABLE OF CONTENTS Organizational Chart & Map Executive Summary Introduction A Discussion & Analysis B MULTI-YEAR BUDGET AND BUSINESS PLANS PUBLIC SAFETY SERVICES: Halifax Regional Fire and Emergency C Halifax Regional Police & RCMP D PUBLIC SERVICES: Halifax Transit E Halifax Public Libraries F Corporate Customer Service G Parks & Recreation H Planning & Development I Transportation and Public Works J GOVERNANCE AND SUPPORT SERVICES: Office of the Auditor General K Chief Administrative Office L Finance, Asset Management & ICT M Human Resources / Office of Diversity and Inclusion N Legal & Legislative Services O FISCAL SERVICES P RESERVES Q GLOSSARY R APPENDICES S HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY CITIZENS OF HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY HALIFAX REGIONAL COUNCIL AUDITOR GENERAL CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER MAYOR’S OFFICE ADMIN STAFF COUNCIL SUPPORT BOARD OF POLICE OFFICE COMMISSIONERS CAO OFFICE HUMAN FINANCE, RESOURCES/ LEGAL & TRANSPORTATION CORPORATE HALIFAX HALIFAX ASSET PLANNING & PARKS & HALIFAX OFFICE OF LEG L ISATIVE & & CUSTOMER REGIONAL FIRE & REGIONAL MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT RECREATION TRANSIT DIVERSITY & PUBLIC WORKS EMERGENCY POLICE & ICT SERVICES SERVICES INCLUSION Fiscal Policy and Employee Litigation Business Services Parks Transit Project Planning Customer Deputy Chief, Executive Officer Planning Relations • • • Operations & Design Contact Centres Operations • • • Solicitor Services Regional Planning Program Support • • • • Deputy Chief Financial Organizational • • Services Bus -

WELCOME APRIL! TABLE of CONTENTS April 1St Is Known As April Fool’S Day When WELCOME APRIL!

WELCOME APRIL! TABLE OF CONTENTS April 1st is known as April Fool’s Day when WELCOME APRIL! ....................................... 1 traditionally, good TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................... 1 APRIL MEETINGS natured pranks are ................................................... 2 HALIFAX REGIONAL COUNCIL SESSIONS ... 2 pulled on friends and family. Lately, due to the BAYERS ROAD & CONNAUGHT AVENUE – global pandemic, there has not been much WASTEWATER SYSTEM MAINTENANCE ...... 2 humour as we deal with increased efforts to CENTRE PLAN PACKAGE B ................................ 3 stop the spread of COVID-19. However, it is HAPPY PASSOVER – APRIL 8 – 16! .................. 4 encouraging to see - via social media - the HAPPY EASTER – APRIL 10 - 13! ....................... 4 creativity of how people are coping with being DISTRICT 9 PARTICIPATORY at home: a makeshift treadmill from a little BUDGET 2020 .................................................. 5 liquid soap and water on a kitchen floor to a COVID-19 UPDATES .............................................. 5 sock puppet used to play a PacMan type game. HRM SPRING AND SUMMER RECREATION Thank you for all you are doing to help PROGRAMMING ..................................................... 6 eliminate this pandemic and for keeping spirits LOCAL POETRY - CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS 8 COUNCILLOR SHAWN CLEARY ........................ 8 high. I look forward to chatting with you at the next Community Drop-In session hopefully in May, at the Chocolate Lake Recreation Centre. April 2020 APRIL MEETINGS BAYERS ROAD & CONNAUGHT AVENUE – WASTEWATER SYSTEM In the interest of public health and safety, all meetings have been cancelled for the month of MAINTENANCE April to help stop the spread of COVID-19. Halifax Water has contracted Eastern Trenches to undertake wastewater system maintenance using innovative cure-in-place-pipe (CIPP) trenchless lining technology. -

Propsoed 2018-19 Multi-Year Halifax

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 3 Budget Committee January 17, 2018 January 19, 2018 TO: Chair and Members of Budget Committee (Standing Committee of the Whole on Budget) SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: January 9, 2018 SUBJECT: Proposed 2018/19 Multi-year Halifax Public Libraries Budget and Business Plan ORIGIN As per Administrative Order 1 and the Budget and Business Plan consultation schedule presented to Regional Council on November 14, 2017, staff is required to present the 2018/19 draft Business Unit Budget and Business Plans to the Budget Committee for review and discussion prior to consideration by Regional Council. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Halifax Charter, section 35 (1) The Chief Administrative Officer shall (b) ensure that an annual budget is prepared and submitted to the Council. RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Budget Committee direct staff to proceed to prepare the 2018/19 Multi-year Halifax Public Libraries Budget and Business Plan, as proposed in the accompanying presentation and consistent with the preliminary fiscal direction. Proposed 2018/19 Multi-year Halifax Public Libraries Budget and Business Plan Budget Committee Report - 2 - January 17, 2018 BACKGROUND As part of the design of the 2018/19 Budget and Business Plan development process, the Budget Committee is reviewing each Business Unit’s budget and proposed plans in advance of detailed HRM Budget and Business Plan preparation. At the December 5, 2017 Committee of the Whole meetings, Regional Council considered and confirmed their Council Priority Outcomes and on December 13, 2017 provided fiscal direction for the 2018/19 multi- year budget, directing staff to: “develop the 2018/19 Multi-year Budget and Business Plans in support of the fiscal direction and approved priorities.” DISCUSSION Staff has prepared the proposed 2018/19 Budget consistent with the preliminary fiscal direction received from Council on December 13, 2017 and aligned with Council Priorities as approved on December 5, 2017. -

![4. Halifax Public Libraries [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8111/4-halifax-public-libraries-pdf-2368111.webp)

4. Halifax Public Libraries [PDF]

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 4 Committee of the Whole February 1, 2017 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council Original Signed SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: January 23, 2017 SUBJECT: Proposed 2017/18 Multi-year Halifax Public Libraries Budget and Business Plan ORIGIN As per Administrative Order 1 and the Budget and Business Plan consultation schedule presented in the Information Report of November 22, 2016, staff is required to present the 2017/18 draft Business Unit Budget and Business Plans to the Committee of the Whole for review and discussion prior to consideration by Regional Council. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Halifax Charter, section 35 (1) The Chief Administrative Officer shall (b) ensure that an annual budget is prepared and submitted to the Council. RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Committee of the Whole direct staff to proceed to prepare the 2017/2018 Multi-year Halifax Public Libraries Budget and Business Plan as proposed in the accompanying presentation, incorporating additional direction provided by motion of Committee of the Whole for inclusion in the proposed HRM 17/18 Multi-year Budget and Business Plan documents. Halifax Public Libraries Feb Proposed 2017/2018 Multi-year Budget and Business Plan Committee of the Whole - 2 - February 1, 2017 BACKGROUND As part of the design of the 2017/2018 Budget and Business Plan development process, the Committee of the Whole is reviewing each Business Unit’s high level budget and proposed plans in -

Canada's Libraries, Archives, and Public Memory

The Royal Society of Canada Expert Panel Report: CANADA’S LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES, AND PUBLIC MEMORY NOVEMBER 2014 Guylaine Beaudry, Concordia University Judith Hare, Halifax Public Libraries Pam Bjornson, National Research Council Ernie Ingles, FRSC, University of Alberta Michael Carroll, American University, Washington College of Law Eric Ketelaar, University of Amsterdam Carol Couture, Université de Montréal Gerald McMaster, Philadelphia Patricia Demers, FRSC, University of Alberta (Chair) Ken Roberts, Hamilton Public Library Charlotte Gray, FRSC, Carleton University CAN.Library and Archives report cover.FINAL.indd 1 14-11-05 10:43 AM CANADA’S LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES, AND PUBLIC MEMORY Prepared and submitted by Guylaine Beaudry, Concordia University Pam Bjornson, National Research Council Michael Carroll, American University, Washington College of Law Carol Couture, Université de Montréal Patricia Demers, FRSC, University of Alberta (Chair) Charlotte Gray, FRSC, Carleton University Judith Hare, Halifax Public Libraries Ernie Ingles, FRSC, University of Alberta Eric Ketelaar, University of Amsterdam Gerald McMaster, Philadelphia Ken Roberts, Hamilton Public Library CANADA’S LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES, AND PUBLIC MEMORY NOVEMBER 2014 A Report of the Royal Society of Canada’s Expert Panel on the Status and Future of Canada’s Libraries and Archives Walter House 282 Somerset St. West Ottawa, ON K2P 0J6, Canada (613) 991-6990 • www.rsc-src.ca ISBN: 978-1-928140-01-6 RSC: EPR 14-2 The report should be cited as follows: Demers, Patricia (chair), Guylaine Beaudry, Pamela Bjornson, Michael Carroll, Carol Couture, Charlotte Gray, Judith Hare, Ernie Ingles, Eric Ketelaar, Gerald McMaster, Ken Roberts. (2014). Expert Panel Report on The Future Now: Canada’s Libraries, Archives, and Public Memory.