We Are the Kingdom of Sicily: Humanism and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

Pena 2013A Prepublication Ms

Evidence for the Use of Raw Materials for the Manufacture of Black-Gloss Ware and Italian Sigillata at Arezzo and Volterra J. Theodore Peña – University of California, Berkeley Abtract A program of compositional analysis involving the mineralogical (optical miscroscopy, petrographic analysis) and chemical (NAA) characterization of Black-Gloss Ware and Italian Sigillata from the site of Cetamura del Chianti along with tiles made from potting clay from several locations in northern Etruria sheds light on the use of raw materials for the manufacture of these two pottery classes at Volterra and Arezzo. The program achieved no textural or chemical matches between the specimens of Black-Gloss Ware of likely Volterran origin and several specimens of clay from outcrops of the Plio-Plestocene marine clay in the environs of Volterra that were very probably employed for the manufacture of this pottery. This suggests that the manufacture of this pottery involved the levigation of the clay. In contrast, an excellent textural and chemical match was obtained between the specimens of Black-Gloss Ware and Italian Sigillata of likely Arretine origin and specimens of the argille di Quarata lacustrine clay (formation agQ) that outcrops along the Torrente Castro/Canale Maestro della Chiana to the west of Arezzo. This indicates that the manufacture of Black-Gloss Ware and Italian Sigillata at Arezzo did not involve the levigation of the clay employed. The agQ formation is overlain by a bed of peat that is effectively unique in peninsular Italy. Peat has been regularly used as a fuel for pottery manufacture in northern Europe, and it seems likely that the producers of these two pottery classes at Arezzo employed it for this purpose. -

Charles V, Monarchia Universalis and the Law of Nations (1515-1530)

+(,121/,1( Citation: 71 Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis 79 2003 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Mon Jan 30 03:58:51 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information CHARLES V, MONARCHIA UNIVERSALIS AND THE LAW OF NATIONS (1515-1530) by RANDALL LESAFFER (Tilburg and Leuven)* Introduction Nowadays most international legal historians agree that the first half of the sixteenth century - coinciding with the life of the emperor Charles V (1500- 1558) - marked the collapse of the medieval European order and the very first origins of the modem state system'. Though it took to the end of the seven- teenth century for the modem law of nations, based on the idea of state sover- eignty, to be formed, the roots of many of its concepts and institutions can be situated in this period2 . While all this might be true in retrospect, it would be by far overstretching the point to state that the victory of the emerging sovereign state over the medieval system was a foregone conclusion for the politicians and lawyers of * I am greatly indebted to professor James Crawford (Cambridge), professor Karl- Heinz Ziegler (Hamburg) and Mrs. Norah Engmann-Gallagher for their comments and suggestions, as well as to the board and staff of the Lauterpacht Research Centre for Inter- national Law at the University of Cambridge for their hospitality during the period I worked there on this article. -

Scenario Book 1

Here I Stand SCENARIO BOOK 1 SCENARIO BOOK T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S ABOUT THIS BOOK ......................................................... 2 Controlling 2 Powers ........................................................... 6 GETTING STARTED ......................................................... 2 Domination Victory ............................................................. 6 SCENARIOS ....................................................................... 2 PLAY-BY-EMAIL TIPS ...................................................... 6 Setup Guidelines .................................................................. 2 Interruptions to Play ............................................................ 6 1517 Scenario ...................................................................... 3 Response Card Play ............................................................. 7 1532 Scenario ...................................................................... 4 DESIGNER’S NOTES ........................................................ 7 Tournament Scenario ........................................................... 5 EXTENDED EXAMPLE OF PLAY................................... 8 SETTING YOUR OWN TIME LIMIT ............................... 6 THE GAME AS HISTORY................................................. 11 GAMES WITH 3 TO 5 PLAYERS ..................................... 6 CHARACTERS OF THE REFORMATION ...................... 15 Configurations ..................................................................... 6 EVENTS OF THE REFORMATION -

Passion for Cycling Tourism

TUSCANY if not HERE, where? PASSION FOR CYCLING TOURISM Tuscany offers you • Unique landscapes and climate • A journey into history and art: from Etruscans to Renaissance down to the present day • An extensive network of cycle paths, unpaved and paved roads with hardly any traffic • Unforgettable cuisine, superb wines and much more ... if not HERE, where? Tuscany is the ideal place for a relaxing cycling holiday: the routes are endless, from the paved roads of Chianti to trails through the forests of the Apennines and the Apuan Alps, from the coast to the historic routes and the eco-paths in nature photo: Enrico Borgogni reserves and through the Val d’Orcia. This guide has been designed to be an excellent travel companion as you ride from one valley, bike trail or cultural site to another, sometimes using the train, all according to the experiences reported by other cyclists. But that’s not all: in the guide you will find tips on where to eat and suggestions for exploring the various areas without overlooking small gems or important sites, with the added benefit of taking advantage of special conditions reserved for the owners of this guide. Therefore, this book is suitable not only for families and those who like easy routes, but can also be helpful to those who want to plan multiple-day excursions with higher levels of difficulty or across uscanyT for longer tours The suggested itineraries are only a part of the rich cycling opportunities that make Tuscany one of the paradises for this kind of activity, and have been selected giving priority to low-traffic roads, white roads or paths always in close contact with nature, trying to reach and show some of our region’s most interesting destinations. -

The Recovery of Manuscripts

Cultural heritage The Recovery of manuscripts David RUNDLE ABSTRACT Manuscripts were the cornerstone of humanism. They had been the main vector for transmission of the ancient texts and culture in the Middle Ages. Most of them had nonetheless been lost or forgotten in remote libraries. In order to recover the ancient Greek and Latin texts they favoured, humanists went on a European quest to find these manuscripts. From Italy, at first, humanists travelled all across Europe, visiting convents and libraries, in search of the lost works of Tacitus, Cicero, etc. building and securing the antique legacy of European culture. Portrait of Poggio holding a manuscript on the first page of the Ruins of Rome (Biblioteca apostolica Vaticana, Urb. Lat. 224, fol. 3). This treatise dedicated to another prominent manuscript hunter, the pope Nicholas V, is a meditation on the loss of Roman culture. Manuscripts were humanism’s lifeblood, its inspiration and its purpose. The production of new books in a new, or revived, style of Latin and with a new, or revived, presentation on the page was central to their activities. But before they could even be conceived, there needed to be classical texts to be imitated. Behind the humanists’ practices lay an agenda of manuscript recovery all across Europe. They were conscious of themselves as cut off from the classical past and set themselves the challenge of discovering works which had not been seen—they said- —by scholars for centuries. In writing of their achievements in doing this, they exaggerated both their own heroic endeavours and the dire state that preceded them. -

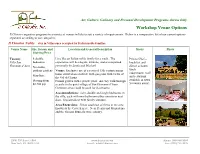

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

The COMICAL HISTORY of ALPHONSUS, KING of ARAGON

ElizabethanDrama.org presents the Annotated Popular Edition of The COMICAL HISTORY of ALPHONSUS, KING OF ARAGON By Robert Greene Written c. 1588-1591 Earliest Extant Edition: 1599 Featuring complete and easy-to-read annotations. Annotations and notes © Copyright Peter Lukacs and ElizabethanDrama.org, 2021. This annotated play may be freely copied and distributed. The COMICAL HISTORY of ALPHONSUS, KING OF ARAGON by ROBERT GREENE Written c. 1588-1591 Earliest Extant Edition: 1599 DRAMATIS PERSONAE: European Characters: Carinus, the rightful heir to the crown of Aragon. Alphonsus, his son. Flaminius, King of Aragon. INTRODUCTION to the PLAY. Albinius, a Lord of Aragon Laelius, a Lord of Aragon There is no point in denying that Alphonsus, King of Miles, a Lord of Aragon Aragon, Robert Greene's first effort as a dramatist, is Belinus, King of Naples. clearly inferior to Christopher Marlowe's Tamburlaine, the Fabius, a Lord of Naples. play (or plays, really) that inspired it. Having said that, a Duke of Millain (Milan). modern reader can still enjoy Greene's tale of his own un- conquerable hero, and will appreciate the fact that, unlike Eastern Characters: the works of other lesser playwrights, Alphonsus does move briskly along, with armies swooping breathlessly on Amurack, the Great Turk. and off the stage. Throw in Elizabethan drama's first talking Fausta, wife to Amurack. brass head, and a lot of revenge and murder, and the reader Iphigina, their daughter. will be amply rewarded. Arcastus, King of the Moors. The language of Alphonsus is also comparatively easy Claramont, King of Barbary. to follow, making it an excellent starter-play for those who Crocon, King of Arabia. -

Mediterranean Studies and the Remaking of Pre-Modern Europe1

Journal of Early Modern History 15 (2011) 385-412 brill.nl/jemh Mediterranean Studies and the Remaking of Pre-modern Europe1 John A. Marino University of California, San Diego Abstract Why have we begun to study the Mediterranean again and what new perspectives have opened up our renewed understanding? This review article surveys recent research in a number of disciplines to ask three questions about Mediterranean Studies today: What is the object of study? What methodologies can be used to study it? And what it all means? The general problem of the object of study in Mediterranean Studies in its ecological, eco- nomic, social, political, and cultural dimensions is introduced in a summary of the works of Pergrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell, Michael McCormick, Chris Wickham, and David Abulafia. Recent methodologies suggested by Peter Burke, Christian Bromberger, Ottomanists, art historians, and literary scholars emphasize both the macro-historical and micro-historical level in order to understand both the local and the regional, material cul- ture and beliefs, mentalities, and social practices as well as its internal dynamics and exter- nal relations. The end results point to three conclusions: the relationship between structures and mechanisms of change internally and interactions externally, comparisons with “other Mediterraneans” outside the Mediterranean, and to connections with the Atlantic World in the remaking of premodern Europe then and now. Keywords Mediterranean, Braudel, Annales school, Purcell, Horden, McCormick, Wickham, Abulafia, Venice, Toledo, Ottoman Empire 1 This paper was originally given as part of a plenary panel, “Trends in Mediterranean Studies,” at the Renaissance Society of America annual meeting in Venice, April 9, 2010. -

Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: the Market for Lemons

_____________________________________________________________________ CREDIT Research Paper No. 12/01 _____________________________________________________________________ Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: The Market for Lemons by Arcangelo Dimico, Alessia Isopi, Ola Olsson Abstract Since its first appearance in the late 1800s, the origins of the Sicilian mafia have remained a largely unresolved mystery. Both institutional and historical explanations have been proposed in the literature through the years. In this paper, we develop an argument for a market structure-hypothesis, contending that mafia arose in towns where firms made unusually high profits due to imperfect competition. We identify the market for citrus fruits as a sector with very high international demand as well as substantial fixed costs that acted as a barrier to entry in many places and secured high profits in others. We argue that the mafia arose out of the need to protect citrus production from predation by thieves. Using the original data from a parliamentary inquiry in 1881-86 on all towns in Sicily, we show that mafia presence is strongly related to the production of orange and lemon. This result contrasts recent work that emphasizes the importance of land reforms and a broadening of property rights as the main reason for the emergence of mafia protection. JEL Classification: Keywords: mafia, Sicily, protection, barrier to entry, dominant position _____________________________________________________________________ Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade, University of Nottingham _____________________________________________________________________ CREDIT Research Paper No. 12/01 Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: The Market for Lemons by Arcangelo Dimico, Alessia Isopi, Ola Olsson Outline 1. Introduction 2. Background and Literature Review 3. The Model 4. -

Images of Homeric Manuscripts from the Biblioteca Marciana1

2008 Annual Conference of CIDOC Athens, September 15 – 18, 2008 Christopher W. Blackwell IMAGES OF HOMERIC MANUSCRIPTS FROM THE BIBLIOTECA MARCIANA1 Christopher W. Blackwell Classics University or Organization: Furman University Address: 3300 Poinsett Highway Greenville, SC 29609 USA E-Mail: [email protected] URL: http://chs.harvard.edu/chs/homer_multitext Abstract This paper describes the manuscript Marcianus Graecus Z.454 (=822), the “Venetus A” and the work of capturing high-resolution digital images of its folios. The manuscripts is a masterpiece of 9th Century “information technology”, combing a primary text, the Homeric Iliad, with secondary texts in the form of scholiastic notes, and other metadata in the form of critical signs. Thus the images of this manuscript provide wide access to an invaluable window into two millennia of the history of the Homeric tradition. INTRODUCTION In May of 2007 an international team of Classicists, conservators, photographers, and imaging experts came together in the Biblioteca Marciana—the Library of St. Mark—in Venice, in order to bring to light a cultural treasure that had been hidden away for over 100 years. The Venetus A manuscript of the Iliad (Marcianus Gr. Z. 454 [=822]), the 1 The following paper is about a collaborative project, of which I am one of four primary editors. We have worked together to produce a number of presentations and publications connected to the project over the past year, including the forthcoming book: Recapturing a Homeric Legacy: Images and Insights from the Venetus A Manuscript of the Iliad. For this reason, this paper should be considered to be co-authored by Casey Dué, Mary Ebbott, and Neel Smith. -

The Latinist Poet-Viceroy of Peru and His Magnum Opus

Faventia 21/1 119-137 16/3/99 12:52 Página 119 Faventia 21/1, 1999119-137 The latinist poet-viceroy of Peru and his magnum opus Bengt Löfstedt W. Michael Mathes University of California-Los Angeles Data de recepció: 30/11/1997 Summary Diego de Benavides A descendent of one of the sons of King Alfonso VII of Castile and León, Juan Alonso de Benavides, who took his family name from the Leonese city granted to him by his father, Diego de Benavides de la Cueva y Bazán was born in 1582 in Santisteban del Puerto (Jaén). Son of the count of Santisteban del Puerto, a title granted by King Enrique IV to Díaz Sánchez in Jaén in 1473, he studied in the Colegio Mayor of San Bartolomé in the University of Salamanca, and followed both careers in letters and arms. He was the eighth count of Santisteban del Puerto, commander of Monreal in the Order of Santiago, count of Cocentina, title granted to Ximén Pérez de Corella by King Alfonso V of Aragón in 1448; count of El Risco, title granted to Pedro Dávila y Bracamonte by the Catholic Monarchs in 1475; and marquis of Las Navas, title granted to Pedro Dávila y Zúñiga, count of El Risco in 1533. As a result of his heroic actions in the Italian wars, on 11 August 1637 Benavides was granted the title of marquis of Solera by Philip IV, and he was subsequently appointed governor of Galicia and viceroy of Navarra. A royal coun- selor of war, he was a minister plenipotentiary at the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659, and arranged the marriage of Louis XIV with the Princess María Teresa of Austria as part of the terms of the teatry1.