P36-40 Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UK Ceramic Manufacturing Strategies, Marketing and Design in Response to Globalization C19902010

Ewins, Neil (2013) UK Ceramic Manufacturing strategies, marketing and design in response to globalization c1990-2010. In: Design and Mobility: The Twenty- Second Annual Parsons/Cooper-Hewitt Graduate Student Symposium on the Decorative Arts and Design, 22 -23 Apr 2013, Theresa Lang Community and Student Center, Arnhold Hall, 55 West 13th Street, 2nd floor, New York. (Submitted) Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/3720/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Neil Ewins. Copy of paper to be delivered at Parsons, The New School of Design, New York on 23rd April 2013, for their 22nd Annual Parsons/Cooper-Hewitt symposium on the Decorative Arts and Design. The Presentation of this paper will be accompanied by Powerpoint imagery. Conference theme ‘Mobility and Design’. Sub-categories of Conference: Globalization and the mobility of cultural products. Paper title: UK ceramic manufacturing strategies, marketing and design, in response to globalization c1990-2010. Since the 1990s, ceramic exports from the Far East have surged, and UK ceramic brands have increasingly utilized cheap labour abroad, known as outsourcing. Much of the more recent behaviour of the UK ceramic industry is a reflection of globalization. Western industries have been described increasingly as ‘post Fordist’ (Amin (ed), 1994), and to many writers the impact of globalization creates deterritorialization (King (ed), 1991, p.6; Tomlinson, 1999, p.106-49). Taking their cue from Baudrillard, Lash and Urry’s analysis of ‘global sociology’ argued that ‘Objects are emptied out both of meaning (and are postmodern) and material content (and are thus post-industrial)’. -

Ashmolean Papers Ashmolean Papers

ASHMOLEAN PAPERS ASHMOLEAN PAPERS 2017 1 Preface 2 Introduction: Obsolescence and Industrial Culture Tim Strangleman 10 Topographies of the Obsolete: Exploring the Site Specific and Associated Histories of Post Industry Neil Brownsword and Anne Helen Mydland 18 Deindustrialisation and Heritage in Three Crockery Capitals Maris Gillette 50 Industrial Ruination and Shared Experiences: A Brief Encounter with Stoke-on-Trent Alice Mah 58 Maintenance, Ruination and the Urban Landscape of Stoke-on-Trent Tim Edensor 72 Image Management Systems: A Model for Archiving Stoke-on-Trent’s Post-Industrial Heritage Jake Kaner 82 Margins, Wastes and the Urban Imaginary Malcolm Miles 98 Biographies Topographies of the Obsolete: Ashmolean Papers Preface First published by Topographies of the Obsolete Publications 2017. ISBN 978-82-690937 In The Natural History of Staffordshire,1 Dr Robert Plot, the first keeper of the Unless otherwise specified the Copyright © for text and artwork: Ashmolean Museum describes an early account of the county’s pre-industrial Tim Strangleman, Neil Brownsword, Anne Helen Mydland, Maris Gillette, Alice Mah, pottery manufacturing during the late 17th century. Apart from documenting Tim Edensor, Jake Kaner, Malcolm Miles potters practices and processes, Plot details the regions natural clays that were once fundamental to its rise as a world renowned industrial centre for ceramics. Edited by Neil Brownsword and Anne Helen Mydland Designed by Phil Rawle, Wren Park Creative Consultants, UK Yet in recent decades the factories and communities of labour that developed Printed by The Printing House, UK around these natural resources have been subject to significant transition. Global economics have resulted in much of the regions ceramic industry outsourcing Designed and published in Stoke-on-Trent to low-cost overseas production. -

Routest W D M LA M I Y N W MARKET a E a a S E I R N E N N M Y L C

M A E S A L N C E E T R T E A S 5 L O R E I R O C A S N O A E T R W T S H N D R R E 0 S G R O A O R L W A E T R E C O L L O D A G T N W O U F E D RO T L 0 RE E L M H O R ST R R H N R K D W T U RY E D Y T E I G E W S C E R E D EE A W L D E OA A T D O A R L N U V O EE A A I R R C T R IL M T O U Y R V T O D S M R R A D S H O E E O N I E O S A L D R K G N R YFFI D R A DA C E E L N C B N D C N E R A G O E E H L E T V A A R R I AL ST A F O TAYLOR RD S R B M L E A N I I G V T I M K A A D T T U D T ST L V S RO I A S P A S D G D Y R S N AD U T N O N IE N S C A Y A A A RO B R N A W D W R R C T E N F I E D R D S E O Abbey H E O A E C L I D R T A E N D N T V T L H A B E O V A B LO R E A E A M N R D A H U S L E YP H R O G A H R L K T S O U D R H C R O R C O O T L W A E L B AD A E E Y R N G F A E V O E O A A S R L C N A M D E O T V AS W E O R T EL R C D V E D R A N R OOT L E D O E T I T E 123 R A E V G O N A E D R M V D R S C R L E A Hulton E N I R N F R O E M S B A V M L V G A E EA M O N W A H L N E T C BA RG LS OO S O O C L C N E A M O S E N WE L H R D LE E A R L G Y R Y D S R D H H P L A R B O W O O O S G R O N S E D N D A S E D E AD L R A F A B L S T D T E R I O W E O T S H I H R O L ST X L N L E L A G M E H A E A H T TWOOD O C T A O V S V G D O U C L O H R C R H A P E E T R L D O E E R L O A A I M E T R O AR N O E S L V X O E U A O N I B R ITGR B M B R E R E A G P D E E A Y O L N T C D A E A D A T P D P O R R D R E E D L A S R E H E T S A T D K E N L IL N H C R C U R T L B D W E O T T N G S D O E A O E R E EROS CRESCE R E E S R E B S NT O B T -

Lot No Description Estimate Estimate Description Lot No

Lot No Description Estimate Lot No Description Estimate 1 Ceramics including Vienna plate, pair £60-£80 17 Dinner ware including Blue and White £20-£40 19thC pink & white continental bisque Willow pattern, Copeland Spode tea pig figures, Alka Bavarian dish, pair ware, decorative plates including continental bisque figures, female a/f Portmeiron Birds of Britain plates and and Staffordshire figure of John Mintons. Wesley. 18 Pair of stoneware wine barrels 6 quart. £20-£40 1a Large pottery figurine, Elephants have £20-£40 32cm h and 27cm h. the right of way, on wooden base. 22cms h. 42cms w of base. 19 Pair of Royal Doulton stoneware slim £30-£50 neck vases, blue ground with tubeline 2 Various ceramics, mainly 19thC, some £10-£20 floral decoration, 29cms. Impressed slight a.f. including 2 Copeland china stamp to base. plates, Wedgwood vase and plate etc. 20 Royal Crown Derby Imari pattern £80-£100 3 Two Parian female figures, both £10-£20 plates. 4 x 27cms, 2 x 18cms and one unmarked. Tallest 34cms h. with blue border, 22.5cms. 4 Two Parian figures of females. 26cms £10-£20 21 Royal Crown Derby selection, coffee £20-£40 h. cup and saucer, one teacup, 2 side plates 18cms (one with gilt rub and chip 5 A Parian figure of Dorothea designed £40-£60 to rim) and a small side plate 16cms. by John Bell with a relief moulded Victorian registration lozenge and 'John 22 Mixed lot of ceramics, Royal Doulton £40-£60 Bell' relief moulded mark. Possibly series plates 27cms w, reproduction art Minton, 34cms h. -

Out Pohery Future

NEWS f~osses di~cuss how to promote city's ceramics VISIT: Lord Mayor of London David Wootton is presented with a specially-made vase by Moorcroft designer Emma Bosson before being shown around Middleport Pottery by the general manager of Burleigh Paul Deighton, right. Pictures: Malcolm Hart Mayor helps map out poHery future BY LOUISE PSYLLIDES formulate an action plan to deliver effect tions to the area he regularly hands out [email protected] ive change for the future. specially-designed Emma Bridgewater "In 1984 there were 66 major ceramics · mugs to guests after Stoke-on-Trent Cent CERAMIC industry leaders met the Lord firms here employing 30,000 people, and ral MP Tristram Hunt put him in touch Mayor of London to discuss how the in 2011 there were 33 employing 8,000. with the firm. Potteries can be promoted all over the "Challenges include the rising cost of He said: "Because of the peculiar world. energy and point of origin marking but nature of the City of London my role is as David Wootton, whose father was born despite all this the Potteries is still much about business as civic respons in Smallthorne, joined representat alive and well with many com ibility. "But I am much more a promoter ives from companies across the city panies continuing to thrive. of UK business as a whole than just one at the Potters Club, in Stoke, yes "While not all manufacturers sector. terday. are producing exclusively in this "I'm very interested to promote Stoke Kevin Oakes, pictured, chief country many are and produc on-Trent as part of the UK economy; and executive of Middleport tableware tion is beginning to return to I'm here to collect messages I can use in manufacturer Steelite, who chaired these shores and to this city." addressing audiences both in the UK and the discussion, said: "This is a Mr Wootton promised to visit abroad. -

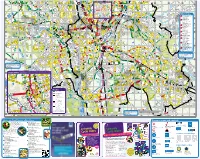

Attractions Events Festivals Exhibitions

Head south for Trentham Gardens (open Complete your trip with a visit to World daily, ticket prices vary, car park on site); of Wedgwood in Barlaston (open daily, occupy the hour-long bus ride or 20 car park on site, free entry to museum, see minute car journey there by downloading website for more details and prices): this and listening to Wedgwood and the award-winning visitor attraction is home War (available on www.appetitestoke. to the UNESCO recognised V&A museum co.uk), an audio artwork drawn from the collection, one of the most important in the Wedgwood Museum’s archive of letters world, spanning from 1759 to the present sent by family members during World War day. You can also book a guided Museum One. Trentham Gardens itself boasts Italian tour to discover even more (guided tours 45 Gardens revived by a Chelsea Flower Show mins, bookable on arrival, £5). From 1 August ATTRACTIONS Gold Medallist, a mile-long, Capability to 23 November is a special World War I Brown-designed lake - complete with eco- exhibition Etruria at War: The Impact of friendly catamaran Miss Elizabeth (every the First World War on Wedgwood and its EVENTS hour, five days a week in summer, £2) - a Employees (10am-5pm, free). Here too you meadow with giant dandelion sculptures, can take a Factory Tour (Monday - Friday, atmospheric woodland trails and much guided tours 45 mins, bookable on arrival, more. The Italian Garden Tearoom serves last entry 3pm. £10 adults, £8 concessions, FESTIVALS traditional Staffordshire oatcakes and under 12s free). See the production process just outside the gardens is Trentham and artisan skills up close, get creative in the Shopping Village, a complex of timber Decorating Studio and Master Craft Studio EXHIBITIONS lodges housing 77 shops and 18 cafés. -

Decorative Arts,Design & Interiors

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Decorative Arts,Design & Interiors Tuesday 5th January 2021 at 10.00 Viewing on a rota basis by appointment only Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Harriet Mustard Helen Bennett Nick Forrester Antiques & Antiques & Antiques & Fine Art Fine Art Fine Art Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 1. A large 20th Century Chinese 6. A quantity of glassware to 14. A quantity of silver plated wares 21. A clear glass pharmaceutical 30. A 20th Century squat cut glass 37. An early 18th Century issue sancai glazed statue of a horse after the include a Victorian blue opaline raised to include mid century modern jug and type bottle of substantial proportions decanter with multifaceted spherical of ‘The Primer set forth by the Kings Tang, a/f with loss to ear, 66.5cm x 64cm bowl with foliated edging and floral sugar bowl on tapered legs, the jug 5cm labelled ‘Liq:Ferri.Iod: 1 to 7’, height stopper, height 27cm, together with majesty and his clergy’, psalms, prayer, -

Attractions Events Festivals Exhibitions

ATTRACTIONS EVENTS FESTIVALS Appetite EXHIBITIONS AND activities happening across the city IN 2018 World of W ed gw o o d T h e F a ir y T ra il a t Tr en th am G ard ens www.visitstoke.co.uk/summer Trentham Gardens Stoke-on-Trent comes alive in the summer As a city of six towns, the challenge is what to pick for your day out… attractions, events, festivals, artisan markets, workshops, talks, shows and exhibitions. Not to mention three Visit England Gold Accolade attractions: World of Wedgwood, The Trentham Estate and the Emma Bridgewater Factory. Many of the summer’s highlights are free and there are plenty of activities for families too, including Heritage Open Days and seasonal events in every town and park. For full details check www.visitstoke.co.uk/summer ry cto Fa er at Spend some time exploring Stoke-on-Trent, and ew g d ri B you’ll discover award-winning museums, exceptional a m m gardens, five Victorian parks, world-renowned E collections and the largest ever find of Anglo- Saxon treasure. Stoke-on-Trent is a place united by a unique history, unrivalled modern industry and an ambitious future: known affectionately as ‘The Potteries’. Designated the ‘World Capital of Ceramics’, Stoke-on-Trent has a proud legacy of making art from the earth: and don’t forget to try the local delicacy - oatcakes! ort Pottery dlep Mid at p ho y S r e y l r l to a c G a t F r A & m u e s u M s e ri te ot P he A T Sto at p ke ers p -on-T mb e rent Reme t it e , M u s e u m o f t he M oo n • Ph oto gra ph b y Carolyn Eaton S pod od e wo Mu g se ed u W m f T o r u ld s r World of Wedgwood t 6 o H e W Wedgwood Drive, Barlaston, r i t SUMMER EVENTS a g Stoke-on-Trent ST12 9ER e C e Explore the museum with free entry, award- Stoke-ON-TRENT Remembers AT n t r A527 e winning factory tours (Monday - Friday), creative THE Potteries Museum & Art Gallery activities, afternoon tea and factory outlet. -

Dowload a Copy of Visitstoke's Experience Stoke-On-Trent Leaflet

EXPERIENCE STOKE-ON-TRENT 2019/20 VISITSTOKE.CO.UK EXPLORE THE WORLD CAPITAL OF CERAMICS... STOKE-ON-TRENT Stoke-on-Trent is a city built on a history of industrial greatness and creative artistic flair. We’ve seen a resurgence of all things that made the city great. From pottery to performing arts and everything in between, we’re home to world-class attractions, incredible talents and creative businesses. A city full of proud people, Stoke-on-Trent is a city moving forward. Come and experience a new chapter in our city’s remarkable story. Located in the heart of England, Stoke-on-Trent is easily accessible by air, road and rail. The following pages will give you a little taste of what you can expect to enjoy on your visit. For full information about attractions, accommodation, events, shopping, culture, and food & drink in Stoke-on-Trent go to visitstoke.co.uk visitstoke visitstoke visit_stoke Contact the Tourist Information Centre on 01782 236000 or email [email protected]. Cover image: Trentham Estate THE POTTERIES Stoke-on-Trent is the World Capital of Ceramics. The city has been shaped by its production of pottery for centuries, building a city with a globally renowned reputation and history of innovation, science, art, culture, and commerce. Today the city remains a must-visit destination for lovers of pottery. Gladstone Pottery Museum Factory tours, outstanding visitor centres, museums and hands-on opportunities including the chance to throw your hand at the potter’s wheel mean you’ll have an entertaining insight into the history and tradition of a time- honoured craft. -

Stoke on Trent and the Potteries from Poynton | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Stoke on Trent and the Potteries from Poynton Cruise this route from : Poynton View the latest version of this pdf Stoke-on-Trent-and-the-Potteries-from-Poynton-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 8.00 to 0.00 Cruising Time : 32.50 Total Distance : 66.00 Number of Locks : 32 Number of Tunnels : 2 Number of Aqueducts : 0 The Staffordshire Potteries is the industrial area encompassing the six towns, Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton that now make up the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. With an unrivalled heritage and very bright future, Stoke-on-Trent (affectionately known as The Potteries), is officially recognised as the World Capital of Ceramics. Visit award winning museums and visitor centres, see world renowned collections, go on a factory tour and meet the skilled workers or have a go yourself at creating your own masterpiece! Buy from the home of ceramics where quality products are designed and manufactured. Wedgwood, Portmeirion, Aynsley, Emma Bridgewater, Burleigh and Moorcroft are just a few of the leading brands you will find here. Search for a bargain in over 20 pottery factory shops in Stoke-on-Trent or it it's something other than pottery that you want, then why not visit intu Potteries? Cruising Notes Day 1 For your first night you will cruise for around two hours, to Clarks Change Bridge No. 29, 5 miles away. -

FREE Treasure Trail Leaflet

To celebrate 10 years since the discovery of the largest treasure of Anglo-Saxon Explore the hidden treasures in gold and silver objects - the Staffordshire Hoard - we’re inviting you to explore the STOKE-ON-TRENT amazing treasures Stoke-on-Trent has & create your own to offer, and share your stories of visiting them by tagging #MyStokeStory on social media. This guide outlines 20 key treasures in and around the city, ranging from the distinctive bottle ovens which stand proud at Gladstone Pottery Museum and Middleport Pottery, to the historic World of Wedgwood; the famous Emma Bridgewater spots; the beautiful Trentham Fairies and many, many more. What’s your Stoke story? We would love to see your photos and hear your stories of So why not make a day of it, or come back for these, and any new or undiscovered treasures in another visit, and see just how many treasures Stoke-on-Trent. Simply tag #MyStokeStory on your social you can experience in our wonderful city? media posts and you’ll be entered into a monthly prize draw to win tickets for up-coming events across the city. For more information on any of these treasures, and lots more amazing cultural destinations in Stoke-on-Trent, please visit www.mystokestory.co.uk Visit • Share • Inspire #MyStokeStory #MyStokeStory SELFIE SPOT MIDDLEPORT POTTERY THE POTTERIES MUSEUM & ART GALLERY OTHER TREASURES Steam Engine SELFIE Ozzy the Owl Staffordshire University Nature Trail 1 SPOT A527 6 7 The First Day’s Vase 8 The Staffordshire Hoard 15 The William Boulton Steam Engine is Ozzy first came to the This vase was thrown on The Staffordshire Hoard is the Staffordshire University has a number of green the last example of a Burslem built world’s attention on an 13th June 1769 by Josiah largest collection of Anglo-Saxon and open areas rich in, and helping to support, engine in its original setting, making it of episode of the BBC’s Wedgwood while his gold and silver metalwork ever biodiversity, including approximately 40 hectares national importance to industrial heritage. -

York Antique Sale

BOULTON & COOPER with Stephensons YORK ANTIQUE SALE YORK SALEROOM (OFF THE A64) - MURTON, YORK. YO19 5GF WEDNESDAY 2ND DECEMBER 10.00am Viewing: Tuesday 1st December - 2.00pm–7:00pm & on morning of sale from 9.00am **** SORRY NO IMAGES AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE **** MISCELLANEOUS 1 - 101 METALWARE 102 - 111 CHINA 112 - 187 GLASSWARE 188 - 203 SILVER, PLATEDWARE & JEWELLERY 204 - 235 BOOKS, PICTURES & PRINTS 236 - 273 FURNITURE 274 - 371 MISCELLANEOUS 1. A Ring Binder and Contents of Stamps including Central African Republic, Comoro Islands and other commemoratives. 2. A Ring Binder and Contents of African Commemoratives, including Central African Republic, Mauritania, etc. 3. A Ring File and Contents of Maltese blocks, Belize, etc. 4. A Binder of mint Isle of Man Stamps. 5. Another Binder and Contents of New Zealand Stamps. 6. A Folder and Contents of GB Stamps including commemoratives, etc. 7. A blue Folder and Contents of world Stamps including Liberia, Korea, Nicaragua, etc. 8. An early 20th century Officer's Service Sword with later painted scabbard, a partridge wood Walking Cane with silver mounts, and two hickory shafted Golf Clubs. 9. A leather Travelling Trunk with lift-off top and inscribed with initials, 2' 3" (69cms) wide. 10. An oak three tier Stationery Rack, 12" (31cms) wide. 11. A blue Favourite Philatelic Album and Contents of British Commonwealth Stamps. 12. A 19th century fret carved wooden Jigsaw in original box by T & J Orme of Manchester, a set of Dominoes in a Wills Star cigarette tin, and some boxwood Draughts. 13. A reproduction oblong Wall Mirror with bevelled plate in gilt frame, 2' 6" (76cms) x 3' 3" (99cms) overall, and a period design oval Wall Mirror in gilt frame.