The Devolution to Township Governments in Zhejiang Province*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOUSE BILL No. 2929

Session of 2006 HOUSE BILL No. 2929 By Representative Horst 2-14 9 AN ACT concerning elections; relating to precinct boundaries; amending 10 K.S.A. 25-26a02 and 25-3801 and repealing the existing sections. 11 12 Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of Kansas: 13 Section 1. K.S.A. 25-26a02 is hereby amended to read as follows: 25- 14 26a02. (a) Election precincts in all counties of the state shall be estab- 15 lished or changed by county election officers in such a manner that: 16 (a) (1) Except as otherwise provided in this section, each election 17 precinct shall be composed of contiguous and compact areas having 18 clearly observable boundaries using visible ground features which meet 19 the requirements of the federal bureau of the census and which coincide 20 with census block boundaries as established by the federal bureau of the 21 census and shall be wholly contained within any larger district from which 22 any municipal, township or county officers are elected; 23 (b) (2) election precincts for election purposes shall be designated 24 consecutively in the county by number or name, or a combination of name 25 and number; 26 (c) (3) any municipal exclave or township enclave shall be a separate 27 precinct and designated by a separate number or name, or combination 28 of name and number, and shall not be identified with or as a part of any 29 other municipal or township precinct; 30 (d) from and after the time that the legislature has been redistricted 31 in 1992, (4) precincts shall be arranged so that no precinct lies -

Ningbo Facts

World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan 213730-00 Final | June 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan Contents Page 1 Executive Summary 4 2 Introduction 10 3 Urban Resilience Methodology 13 3.1 Overview 13 3.2 Approach 14 3.3 Hazard Assessment 14 3.4 City Vulnerability Assessment 15 3.5 Spatial Assessment 17 3.6 Stakeholder Engagement 17 3.7 Local Resilience Action Plan 18 4 Ningbo Hazard Assessment 19 4.1 Hazard Map 19 4.2 Temperature 21 4.3 Precipitation 27 4.4 Droughts 31 4.5 Heat Waves 32 4.6 Tropical Cyclones 33 4.7 Floods 35 4.8 Sea Level Rise 37 4.9 Ningbo Hazard Analysis Summary 42 5 Ningbo Vulnerability Assessment 45 5.1 People 45 5.2 Infrastructure 55 5.3 Economy 69 5.4 Environment 75 5.5 Government 80 6 Gap Analysis 87 6.1 Overview 87 6.2 Natural Disaster Inventory 87 6.3 Policy and Program Inventory 89 6.4 Summary 96 7 Recommendations 97 7.1 Overview 97 7.2 People 103 7.3 Infrastructure 106 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan 7.4 Economy 112 7.5 Environment 115 7.6 Government 118 7.7 Prioritized Recommendations 122 8 Conclusions 126 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan List of Tables Table -

THE CHARTER TOWNSHIP ACT Act 359 of 1947 an ACT to Authorize the Incorporation of Charter Townships; to Provide a Municipal Char

THE CHARTER TOWNSHIP ACT Act 359 of 1947 AN ACT to authorize the incorporation of charter townships; to provide a municipal charter therefor; to prescribe the powers and functions thereof; and to prescribe penalties and provide remedies. History: 1947, Act 359, Eff. Oct. 11, 1947;Am. 1998, Act 144, Eff. Mar. 23, 1999. The People of the State of Michigan enact: 42.1 Short title; charter townships; incorporation; powers, privileges, immunities and liabilities; petition; special census; expenses. Sec. 1. (1) This act shall be known and may be cited as “the charter township act”. (2) A township, having a population of 2,000 or more inhabitants according to the most recent regular or special federal or state census of the inhabitants of the township may incorporate as a charter township. The charter township shall be a municipal corporation, to be known and designated as the charter township of ............................, and shall be subject to this act, which is the charter of the charter township. The charter township, its inhabitants, and its officers shall have, except as otherwise provided in this act, all the powers, privileges, immunities, and liabilities possessed by a township, its inhabitants, and its officers by law and under chapter 16 of the Revised Statutes of 1846, being sections 41.1a to 41.110c of the Michigan Compiled Laws. (3) A special census of the inhabitants of a township desiring to incorporate under this act shall be taken by the secretary of state upon receipt of a petition signed by not less than 100 registered electors of the township. -

ITASCA COUNTY TOWNSHIP OFFICIALS - by Township

ITASCA COUNTY TOWNSHIP OFFICIALS - By Township Township Position Last Name First Name Address City St Zip Phone Term Alvwood Alvwood Community Center 60373 State Hwy 46, Northome MN 56661 Supv A Haberle Don 58006 County Rd 138 Blackduck MN 56630 556-8146 2020 Supv B Bergquist Harold 67058 County Rd 13 Blackduck MN 56630 659-2902 2018 Supv C Olafson Dean 58524 County Road 138 Blackduck MN 56630 368-5665 2018 Clerk/Treas Ungerecht Diane PO Box 123 Northome MN 56661 218-556-7567 Appt. Arbo Arbo Town Hall 33292 Arbo Hall Rd, Grand Rapids MN 55744 Supv A Stanley Kurt 30173 Crestwood Drive Grand Rapids MN 55744 245-3381 2020 Supv C Crowe Lilah 32122 Gunn Park Dr Grand Rapids MN 55744 999-7523 2020 Supv B Pettersen Carter 31963 Arbo Road Grand Rapids MN 55744 327-2422 2018 Treas Stanley Sharon 30173 Crestwood Drive Grand Rapids MN 55744 245-3381 2018 Clerk Johnson Elaine 28915 Bello Circle Grand Rapids MN 55744 245-1196 2020 Ardenhurst Ardenhurst Community Center 66733 State Hwy 46, Northome MN 56661 Supv Martin G. Andy PO Box 13 Northome MN 56661 612-201-8354 2020 Supv Reitan Raymond 63806 State Highway 46 Northome MN 56661 897-5698 2018 Supv Breeze Walter L. P.O. Box 264 Northome MN 56661 897-5023 2018 Treas Stradtmann Angel P.O. Box 32 Northome MN 56661 612-554-7350 2018 Clerk Mull Patricia 65889 Grey Wolf Dr Northome MN 56661 815-693-2685 2020 Balsam Balsam Town Hall 41388 Scenic Hwy, Bovey MN 55709 Supv Heinle Dave 28163 County Road 50 Bovey MN 55709 245-0262 2022 Supv Ackerman Ryan 41037 County Rd 332 Bovey MN 55709 259-4647 2020 Supv Bergren Jerrad 23465 County Road 8 Bovey MN 55709 245-2176 2020 Treas Hoppe Cindy PO Box 272 Calumet MN 55716 245-2022 2020 Clerk Olson Rebecca 24974 County Rd 51 Bovey MN 55709 245-0146 2022 Bearville Bearville Town Hall, 13971 County Road 22, Cook MN 55723 Supv A Radovich George P.O. -

Town Hall Community Center

Indiana Township TOWN HALL COMMUNITY CENTER Welcome to the Town Hall Community Center, located at 3710 Saxonburg Boulevard, Pittsburgh, PA 15238. Entry into Town Hall Community Center As you enter the Town Hall Community Center, you are greeted by a lovely lounge area available to all renters. The Town Hall Community Room hosts up to 120 guests. This room is perfect for a large event such as a graduation party, baby shower, bridal shower or birthday party! The Town Hall Classroom is an informal room that works well for smaller gatherings such as business meetings, classes, children’s birthday parties and small luncheons. This room will host up to 40 guests. The Heat and Serve Kitchen is an important amenity to renters. This area offers an ice machine, warming cabinet, freezer, refrigerator, prep table, microwave and multiple sinks. The patio area is an open area to all renters. Well lit, this area has three picnic tables (ADA accessible) with umbrellas (weather permitting). The patio is the perfect place to relax and enjoy the outdoors. Township of Indiana Town Hall Community Center Rental Information Facility Description Facility Rental Information Facility Rental Fees Facility Rules and Regulations If you are interested in renting space at the Town Hall Community Center, please contact the Community Services Coordinator at 412-767-5333 or by e-mail, [email protected] Monday-Friday, 8:30am-4:30pm to check availability. Township of Indiana 3710 Saxonburg Boulevard Pittsburgh, PA 15238 (412) 767-5333 (412) 767-4773(fax) Let us help you celebrate! Renter must agree to the following: . -

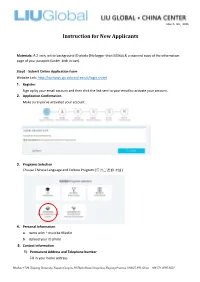

ZJU Instructions for New Applicants

March 5th, 2020 Instruction for New Applicants Materials: A 2-inch, white background ID photo (No bigger than 500kb) & a scanned copy of the information page of your passport (under 1mb in size). Step1 - Submit Online Application Form Website Link: http://isinfosys.zju.edu.cn/recruit/login.shtml 1. Register: Sign up by your email account and then click the link sent to your email to activate your account. 2. Application Confirmation Make sure you’ve activated your account. 3. Programs Selection Choose Chinese Language and Culture Program (汉语言进修项目). 4. Personal Information a. Items with * must be filled in b. Upload your ID photo 5. Contact Information 1) Permanent Address and Telephone Number Fill in your home address Mailbox 1709, Zhejiang University, Yuquan Campus, 38 Zheda Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province 310027, P.R. China +86 571 8795 2051 March 5th, 2020 2) Address to Receive Admission Documents & Telephone Number a. If you are in the States, please fill in your mailing address. (please fill in the English address, otherwise it will affect the accurate postal delivery.) b. If you are out of the States, please fill in the address of China Center. (Copy the information below) Country – China City - HangZhou Postal Code – 310027 Address – Room 303, Building 11, 38 Zheda Road, Zhejiang University Yuquan Campus, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China 3) Current Contacts (Copy the information below) Mailbox 1709, Zhejiang University, Yuquan Campus, 38 Zheda Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province 310027, P.R. China +86 571 8795 2051 March 5th, 2020 Emergency Contact Person – Danyang (Ann) Zheng Emergency Contact Phone Number -13777886407 Emergency Contact Address - Room 303, Building 11, 38 Zheda Road, Zhejiang U niversity Yuquan Campus, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, P.R. -

Critical Language Scholarship Program

CRITICAL LANGUAGE SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM Hangzhou CHINA HANDBOOK FOR PARTICIPANTS SUMMER 2014 The CLS Program is a program of the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. The CLS Program in China is administered by the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, at The Ohio State University. The Ohio State University 398 Hagerty Hall 1775 College Rd. Columbus, OH 43210-1298 Photo courtesy of Prof. Kirk Denton, Department of East Asian Languages The Ohio State University This handbook was compiled and edited by staff of the Critical Language Scholarship East Asian Languages Program at the Ohio State University and adapted from CLS handbooks from American Councils for International Education Contents Contents ......................................................................................................................................................... i Section I: Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Welcome ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Fast Facts ................................................................................................................................................... 6 CLS Program ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Program Staff ....................................................................................................................................... -

Municipality Contact Information Lycoming County Office of Voter Services

Municipality Contact Information Lycoming County Office of Voter Services Anthony Township 911 Address Phone 3260 Quenshukeny Rd (570) 322-6281 Linden, PA 17744 Fax Mailing Address Shelly S. Davis Secretary, Anthony Township 402 Dutch Hill Rd Email Cogan Station, PA 17728 Armstrong Township 911 Address Phone 502 Waterdale Rd (570) 326-6905 Williamsport, PA 17702 Fax Mailing Address Cheryl Kurtz Secretary, Armstrong Township 502 Waterdale Rd Email Williamsport, PA 17702 [email protected] Bastress Township 911 Address Phone 518 Cold Water Town Rd (570) 745-3622 Williamsport, PA 17702 Fax Mailing Address Patricia A. Dincher Secretary, Bastress Township 518 Cold Water Town Rd Email Williamsport, PA 17702 [email protected] 12/22/2020 4:39:20 PM Page 1 of 18 Municipality Contact Information Lycoming County Office of Voter Services Brady Township 911 Address Phone 1986 Elimsport Rd (570) 547-2220 Montgomery, PA 17752 Fax Mailing Address (570) 547-2215 Linda L. Bower Secretary, Brady Township 1986 Elimsport Rd Email Montgomery, PA 17752 [email protected] Brown Township 911 Address Phone 18254 Rt 414 Hwy (570) 353-2938 Cedar Run, PA 17727 Fax Mailing Address (570) 353-2938 Eleanor Paucke Secretary, Brown Township 18254 Rt 414 Hwy Email Cedar Run, PA 17727 [email protected] Cascade Township 911 Address Phone 1456 Kellyburg Rd (570) 995-5099 Trout Run, PA 17771 Fax Mailing Address Gloria J. Lewis Secretary, Cascade Township 1456 Kellyburg Rd Email Trout Run, PA 17771 [email protected] 12/22/2020 4:39:21 PM Page 2 of 18 Municipality Contact Information Lycoming County Office of Voter Services Clinton Township 911 Address Phone 2106 Rt 54 Hwy (570) 547-1466 Montgomery, PA 17752 Fax Mailing Address (570) 547-0900 Janet F. -

SCHOOL ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS with Special Reference to The

SCHOOL ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS With Special Reference to the County Unit By Walter s. Deffenbaugh JANUARY, 1933 HOOL ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE COUNTY UNIT By WALTERS. DEFFENBAUGH Chief, Division of American School Syslems and TIMON COVERT Specialist in School Finance o STATES D EPARTMENT OF THE l NTERI OJ\ - Ray Lyman W ilbur, Ser retary WASII INGTON: 19:1J Price 5 c • ~ui~ NOI !'Ut<' ~:l.t<C UL.,110N SCHOOL ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE COUNTY UNIT The chief purpose of this study is to present (1) an outline of the principal legal provisions relating to the administration of schools in those States that have adopted the county as the unit of school administration for all or some of their counties, and also in .those States that have adopted what is generally considered a semicounty unit plan of school administration, and (2) the principal statutory provisions for county school taxes in each of the States that provide for such taxes. Data showing the total number of school districts and of school board members in each of the States, and a very general description of "district" and town or township units of administration are also included. Classes of units.- The State is the legislative and the administra tive unit in the management and control of the public schools. How ever, much of the actual work of organizing and administering the schools is delegated to subdivisions or districts of State school systems. There are numerous types of these administrative units, varying all the way from the small district, employing but one tencher, to the large county and city school systems, some of which employ hun dreds or even thousands of teachers. -

Wall Township District Map with School Boundaries

MILITARY MILITARY ± SHARK RIVER STATION RD MUNDA RD JUSTIN CIR LIRON LN BOWMAN AVE STATE HWY RT 34 KELLY LN ST MARSHALL RDCATHERINE P L A I N V IE W R D WYCOFF RD ASBURY RD STATE HWY RT 33 R K D OUT LO O CAMPUS PKWY MEADOW WAY GREEN D R F F O C STATE HWY RT 34 Y W MEGILL RD RD OUSE OLH HO SC MEGILL RD WYCKOFF RD WYCKOFF BELMAR BLVD OLHOUSE RD HO SC BELMAR BLVD GARDENSTATE PKWY SPRING ST BELMAR BLVD ST SUE GRACE ST GRACE BELMAR BLVD BIRCHWOOD LN DORIS ST DORIS BROAD ST SHERIDAN DR BIRDSALL RD WALTON WAY D HERITAGE CT R L IA R T S U D IN STATE HWY RT 34 GULLY RD CLAYTON DR WILLIAMS DR REMSEN MILL RD HINK DR MARTIN RD ALICIA D R STATE HWY 18 DR ALICIA DR STANLEY STANLEY FRANCIS DR FRANCIS INDUSTRIAL RD Y BRIGHTON AVE MARCONI RD WA BRIGHTON AVE ROCKAFELLER DR ROCKAFELLER W BLVDRUTA E I V R MARTIN RD E T A RUSTIC CT WOODFIELD AVE W ROMANO BLVD ROMANO Central BUTLER WAY QUERNS RD T R AVE WATSON U SHARPE RD M Elementary School A N C T WESTMINSTER LN BELMAR BLVD Attendance Area DR DANSKIN RD CAMMAR KENNED Y D R RANDOLPH WAY STINES RD LANGDON RD WINDSOR RD WAY PATRIOT REAGAN CT 4TH ST B RA NDO N RD LOUISE CT WOODFIELD AVE 5TH ST DUNROAMIN RD GLENDOLA RD MORRIS LN B 6TH ST DIANA RD PILGRIM RD R DUNHILLWAY TAFT ST A N AIRPORT BLVD DO CORAL WAY QUAKER ST N R D LIBERTY LN ROOSEVELT ST AVENUE A CORAL DOLPHIN DR R 8TH ST MANOR DR WAY D E WASHINGTON AVE SALEM AVE MADISON AVE AVENUE B SQUIRREL RD MANOR R MCKINLEY ST HILLVIEW AVE U ARTHUR ST HARRISON ST PATH Z BELMAR BLVD EVANS RD SHORE DR A HILL AVE MARTIN RD MAYFLOWER DR HADLEY CT MARCONI TALLY HO DR -

Comprehensive Quality Assessment Algorithm for Smart Meters

Article Comprehensive Quality Assessment Algorithm for Smart Meters Shengyuan Liu 1, Fangbin Ye 2, Zhenzhi Lin 1,*, Jia Yang 3, Haigang Liu 2, Yinghe Lin 4 and Haiwei Xie 5 1 College of Electrical Engineering, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China; [email protected] 2 State Grid Zhejiang Electric Power Research Institute, Hangzhou 310014, China; [email protected] (F.Y.); [email protected] (H.L.) 3 State Gird Zhejiang Ningbo Power Supply Company, Ningbo 315000, China; [email protected] 4 Zhejiang Huayun Information Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou 310012, China; [email protected] 5 Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-571-87951625 Received: 24 August 2019; Accepted: 23 September 2019; Published: 26 September 2019 Abstract: With the improvement of operation monitoring and data acquisition levels of smart meters, mining data associated with smart meters becomes possible. Besides, precisely assessing the operation quality of smart meters plays an important role in purchasing metering equipment and improving the economic benefits of power utilities. First, seven indexes for assessing operation quality of smart meters are defined based on the metering data and the Gaussian mixture model (GMM) clustering algorithm is applied to extract the typical index data from the massive data of smart meters. Then, the combination optimization model of index’s weight is presented with the subject experience of experts and object difference of data considered; and the comprehensive assessment algorithm based on the revised technique for order preference by similarity to an ideal solution (TOPSIS) is proposed to evaluate the operation quality of smart meters. -

Chapter 2 Beijing's Internal and External Challenges

CHAPTER 2 BEIJING’S INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CHALLENGES Key Findings • The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is facing internal and external challenges as it attempts to maintain power at home and increase its influence abroad. China’s leadership is acutely aware of these challenges and is making a concerted effort to overcome them. • The CCP perceives Western values and democracy as weaken- ing the ideological commitment to China’s socialist system of Party cadres and the broader populace, which the Party views as a fundamental threat to its rule. General Secretary Xi Jin- ping has attempted to restore the CCP’s belief in its founding values to further consolidate control over nearly all of China’s government, economy, and society. His personal ascendancy within the CCP is in contrast to the previous consensus-based model established by his predecessors. Meanwhile, his signature anticorruption campaign has contributed to bureaucratic confu- sion and paralysis while failing to resolve the endemic corrup- tion plaguing China’s governing system. • China’s current economic challenges include slowing econom- ic growth, a struggling private sector, rising debt levels, and a rapidly-aging population. Beijing’s deleveraging campaign has been a major drag on growth and disproportionately affects the private sector. Rather than attempt to energize China’s econo- my through market reforms, the policy emphasis under General Secretary Xi has shifted markedly toward state control. • Beijing views its dependence on foreign intellectual property as undermining its ambition to become a global power and a threat to its technological independence. China has accelerated its efforts to develop advanced technologies to move up the eco- nomic value chain and reduce its dependence on foreign tech- nology, which it views as both a critical economic and security vulnerability.