Mekelle University College of Business and Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Download/Documents/AFR2537302021ENGLISH.PDF

“I DON’T KNOW IF THEY REALIZED I WAS A PERSON” RAPE AND OTHER SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE CONFLICT IN TIGRAY, ETHIOPIA Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: © Amnesty International (Illustrator: Nala Haileselassie) (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 25/4569/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 9 4. SEXUAL VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND GIRLS IN TIGRAY 12 GANG RAPE, INCLUDING OF PREGNANT WOMEN 12 SEXUAL SLAVERY 14 SADISTIC BRUTALITY ACCOMPANYING RAPE 16 BEATINGS, INSULTS, THREATS, HUMILIATION 17 WOMEN SEXUALLY ASSAULTED WHILE TRYING TO FLEE THE COUNTRY 18 5. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

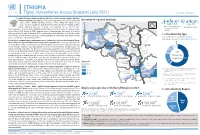

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Modeling Malaria Cases Associated with Environmental Risk Factors in Ethiopia Using Geographically Weighted Regression

MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION Berhanu Berga Dadi i MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING THE GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION MODEL, 2015-2016 Dissertation supervised by Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques,PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain Ana Cristina Costa, PhD Professor, Nova Information Management School University of Nova Lisbon, Portugal Pablo Juan Verdoy, PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain March 2020 ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that the work described in this document is my own and not from someone else. All the assistance I have received from other people is duly acknowledged, and all the sources (published or not published) referenced. This work has not been previously evaluated or submitted to the University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain, or elsewhere. Castellon, 30th Feburaury 2020 Berhanu Berga Dadi iii Acknowledgments Before and above anything, I want to thank our Lord Jesus Christ, Son of GOD, for his blessing and protection to all of us to live. I want to thank also all consortium of Erasmus Mundus Master's program in Geospatial Technologies for their financial and material support during all period of my study. Grateful acknowledgment expressed to Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques, Universitat Jaume I(UJI), Prof.Dr.Ana Cristina Costa, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, and Prof.Dr.Pablo Juan Verdoy, Universitat Jaume I(UJI) for their immense support, outstanding guidance, encouragement and helpful comments throughout my thesis work. Finally, but not least, I would like to thank my lovely wife, Workababa Bekele, and beloved daughter Loise Berhanu and son Nethan Berhanu for their patience, inspiration, and understanding during the entire period of my study. -

Risk Factors and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Human Rabies Exposure in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia

Gebru G, et al. Risk Factors and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Human Rabies Exposure in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia. Annals of Global Health. 2019; 85(1): 119, 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2518 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Risk Factors and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Human Rabies Exposure in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia Gebreyohans Gebru*, Gebremedhin Romha†, Abrha Asefa‡, Haftom Hadush§ and Muluberhan Biedemariam‖ Background: Rabies is a neglected tropical disease, which is economically important with great public health concerns in developing countries including Ethiopia. Epidemiological information can play an important role in the control and prevention of rabies, though little is known about the status of the disease in many settings of Ethiopia. The present study aimed to investigate the risk factors and spatio-temporal patterns of human rabies exposure in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia. Methods: A prospective study was conducted from 01 January 2016 to 31 December 2016 (lapsed for one year) at Suhul general hospital, Northern Ethiopia. Data of human rabies exposure cases were collected using a pretested questionnaire that was prepared for individuals dog bite victims. Moreover, GPS coordinate of each exposure site was collected for spatio-temporal analysis using hand-held Garmin 64 GPS apparatus. Later, cluster of human rabies exposures were identified using Getis-Ord *Gi statistics. Results: In total, 368 human rabies exposure cases were collected during the study year. Age group of 5 to 14 years old were highly exposed (43.2%; 95% CI, 38.2–48.3). Greater number of human rabies exposures was registered in males (63%; 95% CI, 58.0–67.8) than females (37%; 95% CI, 32.1–42.0). -

Amhara Claim of Western and Southern Parts of Tigray

AMHARA CLAIM OF WESTERN AND SOUTHERN PARTS OF TIGRAY By Mathza 11-26-20 We have been hearing and reading about the Amhara Regional State claim of ownership of the Welqayit, Tsegede, Qafta-Humera and Tselemti weredas (hereafter refereed to Welqayit Group) and Raya, and Amhara Regional State threats of war against TPLF/Tigray. One of the threats states “some of the Amhara elite politicians continue to beat drums, as summons to war” (watch/listen) DW TV (Amharic) - July 30, 2020. THE WELQAYIT GROUP Welkayit Amhara Identity Committee (WAIC) was formed in Gonder to return the Welqayit Group from Tigray Regional State to Amhara Regional State. The Welqayit Group was transferred to Tigray during the 1984 reconfiguration of the administrative structure of the country based on ethno-linguistical regional states (kililoch) after the Derg was defeated. It seems that the government of Eritrea has contributed to the Welqayit Group problem. According to ህግደፍንኣሸበርቲ ጉጅለታትን ብአንደበት…ቀዳማይ ክፋል (watch) the Eritrean government had trained Ethiopian oppositions and inculcated opposing views between ethnic groups in Ethiopia, particularly between Amhara and Tigray Regional States, wherever it viewed appropriate for its devilish objective of dismantling Ethiopia. The Committee recruited Tigrayans from Tigray Regional State to do its dirty work. An example is presented in a video, Tigrai Tv:መድረኽተሃድሶ ወረዳ ቃፍታ- ሑመራህዝቢ ጣብያ ዓዲ-ሕርዲ - YouTube (watch) aired on Feb 01, 2017. It shows confessions by a number of Tigrayans from Qafta-Humera who were lured and bribed by the Committee to serve its objectives. Each of them gave details of activities they participated in and carried out against their own people. -

Effect of Senna Obtusifolia (L.) Invasion on Herbaceous Vegetation and Soil Properties of Rangelands in the Western Tigray, Northern Ethiopia Maru G

Gebrekiros and Tessema Ecological Processes (2018) 7:9 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-018-0121-0 RESEARCH Open Access Effect of Senna obtusifolia (L.) invasion on herbaceous vegetation and soil properties of rangelands in the western Tigray, northern Ethiopia Maru G. Gebrekiros1 and Zewdu K. Tessema2* Abstract Introduction: Invasion of exotic plant species is a well-known threat to native ecosystems since it directly affects native plant communities by altering their composition and diversity. Moreover, exotic plant species displace native species through competition, changes in ecosystem processes, or allelopathic effects. Senna obtusifolia (L.) invasion has affected the growth and productivity of herbaceous vegetation in semi-arid regions of northern Ethiopia. Here, we investigated the species composition, species diversity, aboveground biomass, and basal cover of herbaceous vegetation, as well as soil properties of rangelands along three S. obtusifolia invasion levels. Methods: Herbaceous vegetation and soil properties were studied at two locations, Kafta Humera and Tsegede districts, in the western Tigray region of northern Ethiopia under three levels of S. obtusifolia invasion, i.e., non-invaded, lightly invaded, and heavily invaded. Herbaceous plant species composition and their abundance were assessed using a1-m2 quadrat during the flowering stage of most herbaceous species from mid-August to September 2015. Native species were classified into different functional groups and palatability classes, which can be useful in understanding mechanisms underlying the differential responses of native plants to invasion. The percentage of basal cover for S. obtusifolia and native species and that of bare ground were estimated in each quadrat. Similar to sampling of the herbaceous species, soil samples at a depth of 0–20 cm were taken for analyzing soil physical and chemical properties. -

Democracy Under Threat in Ethiopia Hearing Committee

DEMOCRACY UNDER THREAT IN ETHIOPIA HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 9, 2017 Serial No. 115–9 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–585PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:13 Apr 20, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\030917\24585 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. -

Small Scale Hydro Power Development on Selected Existing Irrigation Dam

Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Small Scale Hydro Power Development on existing selected Dams in Tigray Brhane Hntsa Hailu A thesis submitted submitted to the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering stream of Hydraulic Engineering Presented in fulfilment of the requirement for degree of Masters of Science (Civil and Environmental stream of Hydraulic Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis –Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2017 Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of civil and environmental engineering This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Brhane Hntsa, entitled: Small Scale Hydro power Development on Selected existing Irrigation Dam in Tigray and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Sciences (Civil Engineering stream of Hydraulic) complies with the regulation of university and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by Examining committee Advisor __________________________ Signature______________ Date__________ Internal Examiner _____________________ Signature____________ Date___________ External examiner______________________ Signature___________ Date______________ Chairman (department of graduate committee) _______ signature ________Date___________ CERTIFICATION The undersigned certify that he has read the Thesis entitled small scale hydro power development on Existing Selected Dam in Tigray and hereby recommend for acceptance by the Addis Ababa University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. _____________________________ Dr.-Ing. Asie Kemal (Supervisor) ________________________________ Date DECLARATION AND COPY RIGHT I, Brhane Hntsa Hailu, declare that this is my own original work and that it has not been presented and will not be presented to any other University for similar or any degree award. -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Investment Opportunities in Mekelle, Tigray State, Ethiopia

MCI AND VCC WORKING PAPER SERIES ON INVESTMENT IN THE MILLENNIUM CITIES No 10/2009 INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES IN MEKELLE, TIGRAY STATE, ETHIOPIA Bryant Cannon December 2009 432 South Park Avenue, 13th Floor, New York, NY10016, United States Phone: +1-646-884-7422; Fax: +1-212-548-5720 Websites: www.earth.columbia.edu/mci; www.vcc.columbia.edu MCI and VCC Working Paper Series o N 10/2009 Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Karl P. Sauvant, Co-Director, Millennium Cities Initiative, and Executive Director, Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment: [email protected] Editor: Joerg Simon, Senior Investment Advisor, Millennium Cities Initiative: [email protected] Managing Editor: Paulo Cunha, Coordinator, Millennium Cities Initiative: [email protected] The Millennium Cities Initiative (MCI) is a project of The Earth Institute at Columbia University, directed by Professor Jeffrey D. Sachs. It was established in early 2006 to help sub-Saharan African cities achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). As part of this effort, MCI helps the Cities to create employment, stimulate enterprise development and foster economic growth, especially by stimulating domestic and foreign investment, to eradicate extreme poverty – the first and most fundamental MDG. This effort rests on three pillars: (i) the preparation of various materials to inform foreign investors about the regulatory framework for investment and commercially viable investment opportunities; (ii) the dissemination of the various materials to potential investors, such as through investors’ missions and roundtables, and Millennium Cities Investors’ Guides; and (iii) capacity building in the Cities to attract and work with investors. The Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment promotes learning, teaching, policy-oriented research, and practical work within the area of foreign direct investment, paying special attention to the sustainable development dimension of this investment.