Balancing Human Needs and Ecological Function in Forest Fringe and Modified Landscapes of the Southern Western Ghats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master-Plan-Pandalam.Pdf

MASTER PLAN FOR PANDALAM DRAFT REPORT FEBRUARY 2019 PANDALAM MUNICIPALITY DEPARTMENT OF TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING PREFACE A Development Plan for an area details out the overall strategy for proper planning and sustainable development of the area. Development becomes comprehensive when the physical, social and economical variables of an area are planned in an integrated manner. Planning provides protection for the environment, promote and facilitate regeneration, help in creating sustainable communities. Developmental issues are more complex and diverse in urban areas. Hence planned development of urban area is a matter of priority. 74th Constitution amendment act envisages empowerment of the Urban local bodies with planning functions, which is enshrined in the 12th schedule to article 243 (W) of 74th amendment. The Kerala Town and Country Planning Act 2016 also mandates the municipal councils to prepare master plans for the area under their jurisdiction, through a participatory process and the master plan shall generally indicate the manner in which the development shall be carried out and also the manner in which the use of land shall be regulated. In view of this Government of Kerala have undertaken the preparation of the master plans for all statutory towns in the State in a phased manner, under the ‘Scheme of preparation of master plans and detailed town planning schemes’ as per GO (Rt) No 1376/2012/LSGD dated 17/05/2012. The preparation of master plan for Pandalam is included under this scheme. Pandalam is considered as a holy town and is an important point of visit for the pilgrims to Sabariala. It is also a renowned educational and health care centre in central Travancore. -

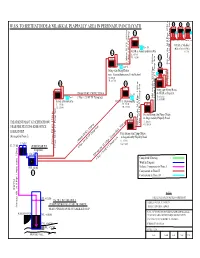

W.S.S. to Seethathode & Nilakkal Plappally Area in Perunadu Panchayath

R6 R7 R8 W.S.S. TO SEETHATHODE & NILAKKAL PLAPPALLY AREA IN PERUNADU PANCHAYATH 20 LL 20 LL 20 LL R3 Zone VI Zone VII Zone VIII 0.3 LL (P) Interconnection 500 mm M.S Pipe, 10 mm thick, 1800 m OHSR at Nilakkal Zone III (Highest Point in PM is R2 GLSR at Gurumandiram (R6) 417.53) IL. 455.00 0.5 LL GL. 452.00 R5 100mm DI K9, 2000 m 2 Nos. 5 HP CF Pump S3 500 mm dia. M.S Pipe, 8250 m 3 Nos. 110 HP VT Pump Sets Zone II Sump cum Pump House 3.5 LL near Gurunathanmannu Tribal School Zone V IL. 290.00 6.0 LL GL. 287.00 3 Nos. 2 HP R1 R4 CF Pump Sets 3.0 LL (P) 3.0 LL Sump cum Pump House 150 mm DI K9 CWPM, 5200 m Zone IV & OHSR at Plapally 500 mm dia. M.S Pipe, 1900 m IL of Sump : Zone I 2 Nos. 12.5 HP CF Pump Sets S2 3 Nos. 175 HP VT Pump Sets IL of OHSR Sump at Kottakuzhy GLSR at Aliyanmukku IL. 175.00 IL. 178.00 6.0 LL GL. 172.00 GL. 175.00 S1 Second Sump cum Pump House in Angamoozhy Plapally Road TREATMENT PLANT AT SEETHATHODU 6.0 LL IL. 266.00 GL. 263.00 500 mm dia. M.S Pipe, 2100 m NEAR FIRE STATION& KSEB OFFICE 3 Nos. 175 HP VT Pump Sets KAKKAD HEP First Sump cum Pump House (Arranged in Phase I) in Angamoozhy Plapally Road 200mm DI K9, 3700 m IL. -

Corporate OFFTCE (SBU-D) B.O.(Frd) No.82112019 (No.D(D&IT)/D-L/Sabarimala/2O19-20/0001) Tvpm, Dated: 06.11.20Te

KERAI-A STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD LIMITED (lncorporated under the Companies Act, 1916) Reg. Office: Vydyuthi Bhavanam, Pattom, Thiruvananthapurarrr (r()'r0t)'1 CIN : U40 100K120 1 1SGC027424 Websilc: wvrinv l.,r'i r Lrr I Phone: +Dt 47I2514685, 2514331, Fax: 0471 2447228 E-mail:dclk:;e b(rrkr,clr.rrr _,I ABSTRACT Sabarimala Festival Season 20L9-20 - Contingency expenditure to the staff posted for cltrty rrt \qbarimala and Nilakkal - Sanctioned - Orders issued. coRPoRATE OFFTCE (SBU-D) B.O.(FrD) No.82112019 (No.D(D&IT)/D-l/Sabarimala/2O19-20/0001) Tvpm, Dated: 06.11.20te. Read:- 1 . Letters No. CE(DS)/AEE iV/Sabarimala/2OL9-201II99 dated 07.09.2019 and 1487 dated 31.10.2019 of the Chief Engineer (Distribution South). 2 . B.o. (Fl-D) No.t922l2018 ( D (D&IT)/D-1/Sabarimalal2078-r910002) dated 13,11.2018. 3 . Note No. D(D&IT)/D-1/Sabarimala/2019-20/0001 dated 01.11.2019 of the Dircctor (Distribution, IT & HRM).(Agenda No.14li1119). ORDER The Chief Engineer (Distribution South) vide letters read as 1" above requested to accord sanction to meet the contingency expenditure in connection with Sabarimala Mandala Makaravilakku Festival 2019-20. It is reported that in this season, Nilakkal would function as a Base Camp for pilgrims and as such more line staff would need to be posted at Nilakkal, Considering the rise in cost of food items, it is also requested to hike contingency expenditurc under Electrical Section, Ranni-Perunad to <2,75,0001- and that for Electrical Section, Kakkad to <1,25,000/- and to accord necessary sanction at the earliest. -

Udayan Tinospora Sinensis.Pmd

Tinospora sinensis in Tamil Nadu P.S. Udayan et al. Gymnema khandalense in Kerala P.S. Udayan et al. Matthew, K.M. (1991). An Excursion Flora of Central Tamil Nadu, and placed it under rare and threatened category. A brief India. The Rapinat Herbarium, St. Joseph College, Thiruchirapalli. description with ecological notes is provided for better Matthew, K.M. (1996). Illustrations on the Flora of the Palni Hills, understanding of this endemic and little known taxon. South India. The Rapinat Herbarium, St. Joseph College, Thiruchirapalli. Matthew, K.M. (1999). The Flora of the Palni Hills, South India, Part. Gymnema khandalense I. The Rapinat Herbarium, St. Joseph College, Thiruchirapalli. Sant., Kew Bull. 1948: 486. 1949 & Rec. Bot. Surv. India 16:52. Nair, N.C., A.N. Henry, G.R. Kumari & V. Chithra (1983). Flora of Tamil Nadu, India, Ser. 1: Analysis. Vol. 1. Botanical Survey of India, 1967; Kothari & Moorthy, J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 80: 259. Calcutta. 1983; Nayar & Sastry, Red Data Book Indian Pl. 3: 37. 1990; Sasi. Pallithanam, J.M. (2001). In: Matthew, K.M. (Ed.). A Pocket Flora & Sivar., Fl. Plants of Thrissur Forests 289. 1996. Bidaria of the Sirumalai Hills, South India. The Rapinat Herbarium, St. Joseph khandalense (Sant.) Jagtap & Singh in Biovigyanam 16 (1): 62. College, Thiruchirapalli. 1990 & Fasc. Fl. India 24. 1999. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Specimens examined: Three mature individuals were observed, The authors are thankful to the authorities of Arya Vaidya Sala (AVS), 20.xi.2003 and 29.xi.2003, Nilakkal to Pampavalley (Attathode), Kottakkal and Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, for forests near Sabarimala, Pathanamthitta District, Kerala State, + the financial support. -

Key Electoral Data of Ranni Assembly Constituency | Sample Book

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-112-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-600-0 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 130 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014 and 2011 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Villages by Population 12-13 -

Report of Rapid Impact Assessment of Flood/ Landslides on Biodiversity Focus on Community Perspectives of the Affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems

IMPACT OF FLOOD/ LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVES AUGUST 2018 KERALA state BIODIVERSITY board 1 IMPACT OF FLOOD/LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY - COMMUnity Perspectives August 2018 Editor in Chief Dr S.C. Joshi IFS (Retd) Chairman, Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram Editorial team Dr. V. Balakrishnan Member Secretary, Kerala State Biodiversity Board Dr. Preetha N. Mrs. Mithrambika N. B. Dr. Baiju Lal B. Dr .Pradeep S. Dr . Suresh T. Mrs. Sunitha Menon Typography : Mrs. Ajmi U.R. Design: Shinelal Published by Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram 2 FOREWORD Kerala is the only state in India where Biodiversity Management Committees (BMC) has been constituted in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporation way back in 2012. The BMCs of Kerala has also been declared as Environmental watch groups by the Government of Kerala vide GO No 04/13/Envt dated 13.05.2013. In Kerala after the devastating natural disasters of August 2018 Post Disaster Needs Assessment ( PDNA) has been conducted officially by international organizations. The present report of Rapid Impact Assessment of flood/ landslides on Biodiversity focus on community perspectives of the affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems. It is for the first time in India that such an assessment of impact of natural disasters on Biodiversity was conducted at LSG level and it is a collaborative effort of BMC and Kerala State Biodiversity Board (KSBB). More importantly each of the 187 BMCs who were involved had also outlined the major causes for such an impact as perceived by them and suggested strategies for biodiversity conservation at local level. Being a study conducted by local community all efforts has been made to incorporate practical approaches for prioritizing areas for biodiversity conservation which can be implemented at local level. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 30.05.2021To05.06.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 30.05.2021to05.06.2021 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kollamannil Veedu PATHANA Njalloor 05-06-2021 677/2021 Azar Ibnu 42, MTHITTA BAILED BY 1 Biju Varghese Athumbumkulam Kumbazha at 10:30 U/s 4(2)(d) Mir Sahib, SI Male (Pathanamth POLICE P.O Konnithazham Hrs of kedo of Police itta) Pathanamthitta PATHANA Kopli Veedu 05-06-2021 676/2021 Abdul 28, MTHITTA Sanju Joseph, BAILED BY 2 Sirajudeen Kumbazha Kannankara at 10:20 U/s 4(2)(d) Samad Male (Pathanamth SI of Police POLICE Pathanamthitta Hrs of kedo itta) Charuvila Veedu PATHANA 05-06-2021 675/2021 31, Kottara Miyannoor Central MTHITTA Sanju Joseph, BAILED BY 3 Aneesh Sadasivan at 10:00 U/s 4(2)(d) Male p.o Pooyappally , junction (Pathanamth SI of Police POLICE Hrs of kedo Kollam itta) 670/2021 U/s 4(2)(d) Viswabhavanam,pa r/w 5 of PATHANA 04-06-2021 Viswambara 29, nnivizha,anandapall Kerala MTHITTA Sunny, SI of BAILED BY 4 Vishnu Kaipattoor at 09:00 n Male y,adoor, Epidemic (Pathanamth Police POLICE Hrs pathanmthitta Diseases itta) Ordinance 2020 Anas ARRESTED - PATHANA cottage,varavila.po. 03-06-2021 669/2021 CJM Abdul 30, Pathanamthitt MTHITTA Johnson.k, SI 5 Aneesh klappana,klappana at 23:15 U/s 465, 468, COURT, kareem Male a (Pathanamth of Police village,karunagappa Hrs 471 IPC PATHANA itta) lly thaluk. -

Pathanamthitta District

Page 1 Price. Rs. 100/- per copy UNIVESITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate by the member of the Local Authorities- 2013-14 (Under Section 17-Elected Members (7) of the Kerala University Act 1974) Electoral Roll of the Members of the Local Authorities- Pathanamthitta District Pathanamthitta Grama Panchayath Roll No. candidate wardno g_wardname h_no h_name place pin 1 SURESHKUMAR.A.K 1 Pandalam Thekkekara PERUMBULLIKKAL 38 Kizhakkevalayath Perumbullikkal 689501 2 AMBIKA.C 2 Pandalam Thekkekara MANNAM NAGAR 299 Kannakunnil Paranthal 689518 3 RAJENDRA PRASAD.S 3 Pandalam Thekkekara PADUKOTTUKAL 300 Thekkecharuvil Thattayil 691525 4 JACOB GEORGE 4 Pandalam Thekkekara KEERUKUZHI Edakunnil Keerukuzhi 689502 BAGAVATHIKKUM 5 BHASKARAN NAIR.M..S 5 Pandalam Thekkekara PADINJARU 299 Pournami Pandalam Thekkekar 689502 6 V.P.VIDHYADARA PANICKAR 6 Pandalam Thekkekara THUDAMALI 494/5 Neyyithakulath Pandalam Thekkekar 691525 7 USHA GURUVARAN 7 Pandalam Thekkekara PARAKKARA 69 A Kuzhivelil puthen veed Parakkara 691525 8 MARYKUTTY.G 8 Pandalam Thekkekara MANKUZHI Mariland Thattayil 691525 9 MANOJ.K.N 9 Pandalam Thekkekara THATTAYIL Thaithondali vadakkethThattayil 691525 10 JAYADEVI.V.P 10 Pandalam Thekkekara MALLIKA 487 Vazhakoottathil kizhakkPandalam Thekkekar 691525 11 SAM ANIYAR 11 Pandalam Thekkekara MAMMOODU Mavila Thekkethil PARANTHAL 689518 12 SUMADEVI.R 12 Pandalam Thekkekara PONGALADI 272 Sree Raghavalayam Pongaladi 689598 13 JANAKI.C.N 13 Pandalam Thekkekara CHERILAYAM 67 Charuvilayil Paranthal 689518 14 SUSAMMA VARGHESE 14 Pandalam Thekkekara -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The liturgy of the Mar Thoma Syrian church of Malabar in the light of its history John, Zacharia How to cite: John, Zacharia (1994) The liturgy of the Mar Thoma Syrian church of Malabar in the light of its history, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5839/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE LITURGY OF THE MAE THOMA SYRIAN CHURCH OF MALABAR IN THE LIGHT OF ITS HISTORY The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived by from it should be acknowledged. Zach&ri® John Submitted for the degree of M.A„ in the faculty of Arts University of Durham 1994 25? 6 - V3 y 1 h FEB 1995 THE LITURGY OF THE MAR THOMA SYRIAN CHURCH OF MALABAR IN THE LIGHT OF ITS HISTORY. -

Kerala History Timeline

Kerala History Timeline AD 1805 Death of Pazhassi Raja 52 St. Thomas Mission to Kerala 1809 Kundara Proclamation of Velu Thampi 68 Jews migrated to Kerala. 1809 Velu Thampi commits suicide. 630 Huang Tsang in Kerala. 1812 Kurichiya revolt against the British. 788 Birth of Sankaracharya. 1831 First census taken in Travancore 820 Death of Sankaracharya. 1834 English education started by 825 Beginning of Malayalam Era. Swatithirunal in Travancore. 851 Sulaiman in Kerala. 1847 Rajyasamacharam the first newspaper 1292 Italiyan Traveller Marcopolo reached in Malayalam, published. Kerala. 1855 Birth of Sree Narayana Guru. 1295 Kozhikode city was established 1865 Pandarappatta Proclamation 1342-1347 African traveller Ibanbatuta reached 1891 The first Legislative Assembly in Kerala. Travancore formed. Malayali Memorial 1440 Nicholo Conti in Kerala. 1895-96 Ezhava Memorial 1498 Vascoda Gama reaches Calicut. 1904 Sreemulam Praja Sabha was established. 1504 War of Cranganore (Kodungallor) be- 1920 Gandhiji's first visit to Kerala. tween Cochin and Kozhikode. 1920-21 Malabar Rebellion. 1505 First Portuguese Viceroy De Almeda 1921 First All Kerala Congress Political reached Kochi. Meeting was held at Ottapalam, under 1510 War between the Portuguese and the the leadership of T. Prakasam. Zamorin at Kozhikode. 1924 Vaikom Satyagraha 1573 Printing Press started functioning in 1928 Death of Sree Narayana Guru. Kochi and Vypinkotta. 1930 Salt Satyagraha 1599 Udayamperoor Sunahadhos. 1931 Guruvayur Satyagraha 1616 Captain Keeling reached Kerala. 1932 Nivarthana Agitation 1663 Capture of Kochi by the Dutch. 1934 Split in the congress. Rise of the Leftists 1694 Thalassery Factory established. and Rightists. 1695 Anjengo (Anchu Thengu) Factory 1935 Sri P. Krishna Pillai and Sri. -

Offers Invitating for Land Survey- Nilakkal-HPC, Sabarimala

No.01/HPC/SMP/NKL-SY/2017-18 Dated 13.04.2018 OFFERS INVITED FOR SURVEYING AND MAPPING NILAKKAL AREA The High Power Committee for Implementation of Sabarimala Master Plan invites Competitive Offers /Quotations from the reputed Survey Agencies in Kerala for 110 ha. of land at Nilakkal (predominantly vacant land) in Pathanamthitta district under the possession and use by the Travancore Devaswom Board so as to reach the office of the undersigned on or before 5.00 PM on 21.04.2018. The Survey requirements are given below: 1. Total Station Contour Survey - 1m contour interval 2. Spot levels at grid intervals of min 10m x10m -contour mapping 3. All structures and their plinth levels/top levels to be marked 4. Roads to be marked with spot levels at 5m interval 5. Culverts, streams, wells, channels, water tanks etc. to be marked with invert levels 6. Waterbodies, lakes, ponds etc to be marked with max flood levels, current water level etc. 7. All major trees to be marked 8. Giant trees such as Ficus, bamboo clusters to be marked separately with indicative legend 9. Large rock formations to be marked 10. Plantations to be marked in groups 11. Electrical / Communication lines and posts to be marked 12. Benchmark to be marked in the presence of Departmental Officials and linked to MSL 13. The Map to a scale of 1 : 2500 should be completely dimensioned so that any structure or installation can be located from visible land marks Rate per hectare should be quoted Earnest Money Deposit : Rs. 5,000/- in the form of deposit receipt from any of the nationalised / schedule banks pledged in favour of the undersigned Deliverables : Five hard copies along with soft copy Time Schedule : Work should be completed within One Month from the date of award of Contract Payment Terms : Payment shall be made on completion of work which can be settled on the actual area of land surveyed and mapped as per requirements For further details contact [email protected] and www.travancoredevaswomboard.org. -

District Wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt

District wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt. Model HSS For Boys Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42007 Govt V H S S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42008 Govt H S S For Girls Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42010 Navabharath E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42011 Govt. H S S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42012 Sr.Elizabeth Joel C S I E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42013 S C V B H S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42014 S S V G H S S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42015 P N M G H S S Koonthalloor Thiruvananthapuram 42021 Govt H S Avanavancheri Thiruvananthapuram 42023 Govt H S S Kavalayoor Thiruvananthapuram 42035 Govt V H S S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42051 Govt H S S Venjaramood Thiruvananthapuram 42070 Janatha H S S Thempammood Thiruvananthapuram 42072 Govt. H S S Azhoor Thiruvananthapuram 42077 S S M E M H S Mudapuram Thiruvananthapuram 42078 Vidhyadhiraja E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42301 L M S L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42302 Govt. L P S Keezhattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42303 Govt. L P S Andoor Thiruvananthapuram 42304 Govt. L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42305 Govt. L P S Melattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42306 Govt. L P S Melkadakkavur Thiruvananthapuram 42307 Govt.L P S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42308 Govt. L P S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42309 Govt. L P S Madathuvathukkal Thiruvananthapuram 42310 P T M L P S Kumpalathumpara Thiruvananthapuram 42311 Govt. L P S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42312 Govt. L P S Mullaramcode Thiruvananthapuram 42313 Govt. L P S Ottoor Thiruvananthapuram 42314 R M L P S Mananakku Thiruvananthapuram 42315 A M L P S Perumkulam Thiruvananthapuram 42316 Govt.