Audience Attendance Trends 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Applications 9/30/2013

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28084 Broadcast Applications 9/30/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING MA BAL-20130822AER WBEC 2714 GAMMA BROADCASTING, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended E 1420 KHZ MA , PITTSFIELD From: GAMMA BROADCASTING, LLC To: GREG REED Form 314 MA BAL-20130822AES WUPE 71436 GAMMA BROADCASTING, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended E 1110 KHZ MA , PITTSFIELD From: GAMMA BROADCASTING, LLC To: GREG REED Form 314 CLASS A TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING GA BALTVA-20130925ANZ WBFL-CA 48763 NEW AGE MEDIA OF Voluntary Assignment of License TALLAHASSEE LICENSE, LLC E CHAN-13 From: NEW AGE MEDIA OF TALLAHASSEE, LLC GA , VALDOSTA To: TALLAHASSEE (WTLH-TV) LICENSEE, INC. Form 314 GA BALTTA-20130925AOA WBVJ-LP 23487 NEW AGE MEDIA OF Voluntary Assignment of License TALLAHASSEE LICENSE, LLC E CHAN-35 From: NEW AGE MEDIA OF TALLAHASSEE, LLC GA , VALDOSTA To: TALLAHASSEE (WTLH-TV) LICENSEE, INC. Form 314 FL BALTTA-20130925AOE WYME-CA 7726 NEW AGE MEDIA OF Voluntary Assignment of License GAINESVILLE LICENSE, LLC E CHAN-45 From: NEW AGE MEDIA OF GAINESVILLE LICENSE, LLC FL , GAINESVILLE To: WGFL LICENSEE, LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 53 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. -

Fact Sheet Campusmap 2019

UNIVERSITY OF OREGON FACILITIES FACT SHEET 2019 MARTIN LUTHE R KING JR BLVD Hatfield-Dowlin Complex Football Practice Fields PK Park Casanova Autzen Athletic Brooks Field LEO HARRIS PKW Y Moshofsky Sports Randy and Susie Stadium Pape Complex W To Autzen illa Stadium Complex me tte Riverfront Fields R Bike Path iv er FRANKLIN BLVD Millrace Dr Campus Planning and Garage Facilities Management CPFM ZIRC MILLRACE DR Central Admin Fine Arts Power Wilkinson Studios Millrace Station Millrace House Studios 1600 Innovation Woodshop Millrace Center Urban RIVERFRONT PKWY EAST 11TH AVE Farm KC Millrace Annex Robinson Villard Northwest McKenzie Theatre Lawrence Knight Campus Christian MILLER THEATRE COMPLEX 1715 University Hope Cascade Franklin Theatre Annex Deady Onyx Bridge Lewis EAST 12TH AVE Pacific Streisinger Integrative PeaceHealth UO Allan Price Science University District Annex Computing Allen Cascade Science Klamath Commons MRI Lillis LOKEY SCIENCE COMPLEX MOSS ST LILLIS BUSINESS COMPLEX Willamette Huestis Jaqua Lokey Oregon Academic Duck Chiles Fenton Friendly Store Peterson Anstett Columbia Laboratories Center FRANKLIN BLVD VILLARD ST EAST 13TH AVE Restricted Vehicle Access Deschutes EAST 13TH AVE Volcanology Condon Chapman University Ford Carson Watson Burgess Johnson Health, Boynton Alumni Collier ST BEECH Counseling, Collier Center Tykeson House and Testing Hamilton Matthew Knight Erb Memorial Cloran Unthank Arena JOHNSON LANE 13th Ave Union (EMU) Garage Prince Robbins COLUMBIAST Schnitzer McClain EAST 14TH AVE Lucien Museum Hawthorne -

Hillsboro W123 03 20

Oregon Directory of Radio (541) 687 -3370. Fax: (541) 687 -3573. Web Site: www.krvm.com. KWVZ(FM)-Not on air. target date: unknown: 91.7 mhz: w horiz. KMUZ(AM)-Licensed to Gresham. See Portlana Licensee: Lane County School District 4J. (acq 1- 10.97) Rep: 40 w vert. 1,601 ft. TL: N44 07 28 W124 00 41. 139 Susan Campbell McGavren Guild. Format: World news, sports. Carl Sundberg, gen Hall, University of Oregon. Eugene (97403). (541) 345-0800. Harbeck-Fruitdale mgr & chief of engrg. Licensee: Oregon State Board of Higher Education. Paul C. Bjomstad, gen mgr. KLDR(FM)- May 3, 1991: 98.3 mhz; 185 w. 2.096 ft. TL: N42 22 56 KRVM -FM- Dec 8, 1947: 91.9 mhz; 1.9 kw. -36 ft. TL: N44 03 44 W123 16 29. Stereo. Hm opn: 24. Rebroadcasts KAJO(AM) Grants W123 06 17. (CP: 1.12 kw, ant 98 ft.). Stereo. Hrs opn: 20. (541) Gleneden Beach Pass 888 Rogue River Hwy., Grants Pass (97527). (541) 474 -7292. 687 -3147. Web Site: www.krvm.com. Licensee: School District 4 J Fax: (541) 474 -7300. E -mail: kdrOkldr.com. Web Site: www.kldr.com. Lane County. Net: NPR. Format: AAA, AOR, blues. News progmg 3 KSHL(FM)- December 1992: 97.5 mhz; 17 kw. 843 ff. TL: N44 45 22 Licensee: Grants Pass Broadcasting Corp. *Net: AP. Format: Adult hrs wkly. Target aud: General. Spec grog: Black 2 hrs, country one hr, W124 02 57. Stereo. Hrs opn: 24. Box 1180, 644 S.W. Coast Hwy., contemp. -

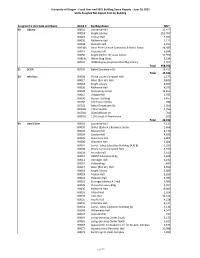

June 30, 2021 Units Assigned Net Square Feet by Building

University of Oregon - Fiscal Year-end 2021 Building Space Reports - June 30, 2021 Units Assigned Net Square Feet by Building Assigned To Unit Code and Name BLDG # Building Name NSF* 20 Library B0001 Lawrence Hall 12,447 B0018 Knight Library 261,767 B0019 Fenton Hall 7,924 B0030 McKenzie Hall 1,112 B0038 Klamath Hall 3,012 B0038A Allan Price Science Commons & Rsch Library 24,383 B0047 Cascade Hall 6,994 B0050 Knight (Wllm. W.) Law Center 31,592 B0814L White Stag Block 5,534 B0903 OIMB Rippey (Loyd and Dorothy) Library 3,997 Total 358,762 21 SCUA B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 15,422 Total 15,422 30 Info Svcs B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 1,375 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 3,826 B0018 Knight Library 8,305 B0030 McKenzie Hall 4,973 B0039 CompUting Center 13,651 B0042 Oregon Hall 2,595 B0090 Rainier BUilding 3,457 B0156 Cell Tower Utility 288 B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 1,506 B0726L 1715 Franklin 1,756 B0750L 1600 Millrace Dr 700 B0891L 1199 SoUth A WarehoUse 500 Total 42,932 99 Genl Clsrm B0001 Lawrence Hall 7,132 B0002 Chiles (Earle A.) BUsiness Center 2,668 B0003 Anstett Hall 3,176 B0004 Condon Hall 4,696 B0005 University Hall 6,805 B0006 Chapman Hall 3,404 B0007 Lorry I. Lokey EdUcation BUilding (A & B) 2,016 B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 6,339 B0009 Friendly Hall 2,610 B0010 HEDCO EdUcation Bldg 5,648 B0011 Gerlinger Hall 6,192 B0015 Volcanology 489 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 4,650 B0018 Knight Library 5,804 B0019 Fenton Hall 3,263 B0022 Peterson Hall 3,494 B0023 Esslinger (ArthUr A.) Hall 3,965 B0029 Clinical Services Bldg 2,467 B0030 McKenzie Hall 19,009 B0031 Villard Hall 1,924 B0034 Lillis Hall 24,144 B0035 Pacific Hall 4,228 B0036 ColUmbia Hall 6,147 B0041 Lorry I. -

Oregon Media Outlets

Oregon Media Outlets Newswire’s Media Database provides targeted media outreach opportunities to key trade journals, publications, and outlets. The following records are related to traditional media from radio, print and television based on the information provided by the media. Note: The listings may be subject to change based on the latest data. ________________________________________________________________________________ Radio Stations 28. KKNU-FM [New Country 93] 1. All Things Considered 29. KLAD-FM [92.5 KLAD] 2. Cooking Outdoors w/ Mr. BBQ 30. KLCC-FM 3. Green Tips 31. KLDZ-FM [Kool 103.5] 4. GROUND ZERO WITH CLYDE LEWIS 32. KLOO-AM [Newsradio 1340 (KLOO)] 5. Honky Tonk Hour 33. KLOO-FM [106.3 KLOO] 6. Jefferson Public Radio 34. KMED-AM [NewsTalk 1440] 7. K218AE-FM 35. KMGE-FM [Mix 94.5] 8. K265CP-FM 36. KMGX-FM [Mix 100.7] 9. K283BH-FM 37. KMHD-FM 10. KACI-AM [Newsradio 1300] 38. KMUN-FM 11. KACI-FM [K-C 93.5] 39. KMUZ-FM 12. KBCC-LP 40. KNRK-FM [94/7 Alternative Portland] 13. KBCH-AM 41. KNRQ-FM [Alternative 103.7 NRQ] 14. KBFF-FM [Live 95-5] 42. KODL-AM [Radio Freshing] 15. KBND-AM [Newstalk 1110] 43. KODZ-FM [KOOL 99.1] 16. KBOO-FM [K-Boo] 44. KPFA-FM [Pacifica Radio] 17. KCFM-AM 45. KPNW-AM [Newsradio 1120] 18. KCMX-FM [Lite 102] 46. KPOV-FM 19. KCUW-LP 47. KPSU-AM 20. KDUK-FM [104.7 KDUK] 48. KPVN-LP 21. KDYM-AM [Juan] 49. KRCO-AM 22. KEC42-FM 50. KRKT-FM [99.9 KRKT] 23. -

Student-Parent Handbook MONROE GRADE SCHOOL STUDENT-PARENT HANDBOOK GRADES K-8 TABLE of CONTENTS

MONROE GRADE SCHOOL Student-Parent Handbook MONROE GRADE SCHOOL STUDENT-PARENT HANDBOOK GRADES K-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page Number PRELIMINARY PAGES: Monroe School District Calendar 1 letter from the Principal 2 The Dragon Code 3 Staff Directory 4 Lunch and Breakfast Program 5 Monroe Grade School Meal Price list 6 Discrimination Clause 7 ACCIDENTS 8 ADMISSION 8 ANIMALS 8 ASBESTOS 8 ATHLETICS 8 ATTENDANCE 8 BICYCLES, SKATEBOARDS, ROLLER BLADES AND SCOOTERS 9 BUILDING HOURS 9 BUS RULES 9 CELL PHONES AND ELECTRONIC DEVICES 10 COMMUNICABLE DISEASES 11 CONFERENCES 11 DRESS AND GROOMING 11 DISCRIMINATION, COMPLAINT, AND GRIEVANCE PROCEDURES 12 EMERGENCY EVACUATION DRILLS 12 EMERGENCY SCHOOL CLOSURE INFORMATION 13 FIELD TRIPS 13 FOOD SAFETY 13 GUM 14 HARASSMENT, INTIMIDATION, BULLYING, CYBERBULLYING, AND HAZING 14 HEALTH SERVICES 14 IMMUNIZATIONS 16 LOCKERS AND DESKS 16 LOST AND FOUND 16 MONROE SCHOOL-BASED HEALTH CLINIC 17 PARKING LOT PROCEDURES 17 PROGRESS REPORTS 17 REGISTRATION 17 STUDENT GOVERNMENT 17 STUDENT RECORDS 18 TALENTED AND GIFTED 18 TELEPHONES 19 TEXTBOOKS 19 TOBACOO FREE SCHOOLS 19 VOLUNTEERS AND PARENT INVOLVEMENT 19 APPENDIX 20 -~r=- 2020-21 Monroe School District #1J Approved 5/ 11 /20 JULY JANUARY 4 C lasses resume s M w Th F s 18 No School: M LK Jr. Day 2 3 4 21 End 1" Semester 22 No School: Teacher w orkday 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 JO 31 - - -- AUGUST FEBRUARY 3 1 K-I2 Stoff Pro f Dev 15 No School: Prcsirlr.nl's Day s M T w Th s 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 II 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 2 1 22 21 22 23 24 26 27 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 28 JO SEPTEMBER t K- 12 Tr.ocher Wo rkday ~19 End o f 3 Qt r, Teacher workday s s 2 K-I2 Teacher Prof Dev 22-26 No School: Spring Break 5 3 K-12 Te acher Workday 3 K-8 Parent O rientation 3-7 PM 6 12 •I 9-12 FR&Ncw student oncntoHo n 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 4 K-8 Non contract doy 7 Lobo, Doy. -

2020 Fact Sheet Edition Draft Copy

UNIVERSITY OF OREGON FACILITIES FACT SHEET 2020 EDITION MARTIN LUTHE R KING JR BLVD Hatfield-Dowlin Complex Football Practice Fields PK Park Casanova Autzen Athletic Brooks Field LE O H A R Moshofsky R IS Sports P K W Y Randy and Susie Stadium Pape Complex W To Autzen illa Stadium Complex me tte Riverfront Fields R Bike Path iv er FR A N K Millrace Dr L IN Campus Planning and Garage B LV D Facilities Management CPFM ZIRC Y MILLRACE DR Central Admin W Fine Arts K P Power Studios Wilkinson T M Station Millrace N illra House O Innovation ce Studios R 1600 F Woodshop R Millrace Center E V I Urban R EAST 11TH AVE Farm KC Millrace Annex Robinson Villard Northwest McKenzie Theatre Lawrence Knight Campus Christian MILLER THEATRE COMPLEX 1715 University HoPe Cascade Franklin Theatre Annex Lewis EAST 12TH AVE University Onyx Bridge Pacific Integrative T Hall Streisinger S PeaceHealth UO Allan Price Science S University District Annex Computing Allen Cascade Science Klamath S Commons MRI O Lillis L O K E Y S C I E N C E C O M P L E X M T LILLIS BUSINESS COMPLEX S Willamette Huestis Jaqua Lokey Oregon D Duck Chiles Friendly Academic R Fenton Columbia A Peterson Anstett Laboratories Center L Store L I FRA V EAST 13TH AVE Deschutes NKL Restricted Vehicle Access T EAST 13TH AVE IN B S LV D Volcanology Condon Chapman H University C Watson BurGess Ford Carson E Health, B T Johnson E oy r Alumni nt lie S o l Collier B Counseling, n Co A Center Tykeson I House and Testing Hamilton B Matthew Knight Erb Memorial Cloran Unthank M Arena JOHNSON LANE U 13th -

11 Units ASF Occupied by Bldg FY21

University of Oregon - Fiscal Year-end 2021 Building Space Reports - June 30th, 2021 Units Assigned Net Square Feet Occupied by Building Assigned To Unit Code and Name Loaned To Unit Code and Name BLDG # Building Name NSF* 20 Library . B0001 Lawrence Hall 12,447 B0018 Knight Library 257,306 B0019 Fenton Hall 7,924 B0030 McKenzie Hall 1,112 B0038 Klamath Hall 2,412 B0038A Allan Price Science Commons & Rsch Library 23,905 B0047 Cascade Hall 6,994 B0050 Knight (Wllm. W.) Law Center 31,592 B0814L White Stag Block 5,534 B0903 OIMB Rippey (Loyd and Dorothy) Library 3,997 701 CIS B0038 Klamath Hall 600 1513 Cinema StUdies B0018 Knight Library 2,575 7330 Univ HoUsing B0018 Knight Library 194 B0038A Allan Price Science Commons & Rsch Library 478 7475 TAE Center B0018 Knight Library 916 9801 OR Folklife B0018 Knight Library 776 Total 358,762 21 SCUA . B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 15,422 Total 15,422 30 Info Svcs . B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 1,375 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 3,826 B0018 Knight Library 7,683 B0030 McKenzie Hall 4,973 B0039 CompUting Center 13,651 B0042 Oregon Hall 2,595 B0090 Rainier BUilding 3,457 B0156 Cell Tower Utility 288 B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 1,506 B0726L 1715 Franklin 1,756 B0750L 1600 Millrace Dr 700 B0891L 1199 SoUth A WarehoUse 500 1513 Cinema StUdies B0018 Knight Library 622 Total 42,932 99 Genl Clsrm . B0001 Lawrence Hall 5,702 B0002 Chiles (Earle A.) BUsiness Center 1,107 B0003 Anstett Hall 3,176 B0004 Condon Hall 3,667 B0005 University Hall 6,805 B0006 Chapman Hall 1,820 B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 5,987 B0009 Friendly Hall 1,623 B0010 HEDCO EdUcation Bldg 2,258 B0011 Gerlinger Hall 5,356 B0015 Volcanology 489 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 3,352 B0018 Knight Library 3,424 B0019 Fenton Hall 2,740 B0022 Peterson Hall 3,494 B0023 Esslinger (ArthUr A.) Hall 3,965 B0029 Clinical Services Bldg 1,878 B0030 McKenzie Hall 16,902 B0031 Villard Hall 1,924 B0034 Lillis Hall 11,122 B0035 Pacific Hall 3,392 B0036 ColUmbia Hall 6,147 B0041 Lorry I. -

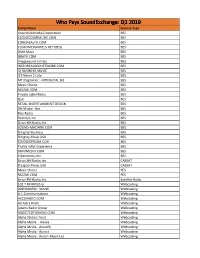

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

UO Buildings by Address - Updated November, 2018

UO Buildings By Address - Updated November, 2018 BUILDING BUILDING NAME ADDRESS NUMBER Agate Street 84 Hamilton Complex West - Boynton Hall 1325 Agate 84 Hamilton Complex West - Cloran Hall 1355 Agate 84/85 Hamilton Hall Complex (West/East core) 1365 Agate 84 Hamilton Complex West - McClain Hall 1385 Agate 84 Hamilton Complex West - Tingle Hall 1395 Agate 78 Walton Complex South - Dyment Hall 1408 Agate 78 Walton Complex South - Hawthorne Hall 1410 Agate 78 Walton Complex South - McAlister Hall 1412 Agate 78 Walton Complex South - Schaffer Hall 1420 Agate 77/78 Walton Complex - Loading Dock 1440 Agate 77 Walton Complex North - Sweetser Hall 1460 Agate 50 William W. Knight Law Center 1515 Agate 61 Hayward Field Weight room 1650 Agate 56 Hayward Field Maintenance/Storage 1690 Agate 87A Labor Education & Research Center (LERC) 1675 Agate 87B Military Science 1679 Agate 147 Agate Hall 1787 Agate 148 Agate House 1795 Agate Alder Street 10 HEDCO Education Building 1655 Alder 7 Lorry I. Lokey Education Building (west wing former Univ High 1571 Alder (east wing 1580 Kincaid; south wing School) 877 E. 16th) 10 HEDCO Education Building 1655 Alder Beech Street 76 Carson Hall 1320 Beech (loading dock only: 1450 E. 13th) Broadway 702 Baker Downtown Center, Center Bldg 318 E. Broadway 702 Baker Downtown Center, North Bldg (see also High Street) 328 E. Broadway Centennial Loop 707L KWAX 75 Centennial Loop Columbia Street and Columbia Alley 85 Hamilton Complex East - Collier Hall 1320 Columbia 91 Columbia Garage 1355 Columbia 85 Hamilton Complex East -

Executive Session News Media Attendance Policy

CITY OF SILVERTON EXECUTIVE SESSION NEWS MEDIA ATTENDANCE POLICY WHEREAS Oregon Public Meetings Law provides that representatives of the news media shall be allowed to attend certain executive sessions of public bodies, but may be required to not disclose specified information (ORS 192.660(4)); and WHEREAS the City of Silverton finds that in the absence of a statutory definition of "news media" as that term is used in ORS 192.660(4) it is necessary to adopt a policy that implements the intent of the Public Meetings Law relating to executive session attendance without precluding attendance by Internet-based or other "non-traditional" information disseminators that are institutionalized and committed to compliance with ORS 192.660(4); and WHEREAS the City of Silverton recognizes that this policy is solely for the purpose of determining eligibility to attend executive sessions, which requires non-disclosure of specified information from executive sessions, and is not intended to otherwise define "news media" or to determine eligibility to report on Silverton activities or to limit access to other Silverton meetings by any person; The City of Silverton hereby adopts the following policy: 1. Recognized News Media Organizations. The following entities are hereby recognized as news media organizations eligible to attend executive sessions because they have an established history of meeting the requirements of this policy: Main Media Contact and Affiliates Print: Portland The Oregonian Mt. Angel Our Town Salem Statesman Journal Salem The Capital Press Silverton The Appeal Tribune Radio: KUGN AM 590 KPNW KORE KAGI AM 930 KDUK KRVM KEX AM 1190 KODZ KWVA KOPB FM 91.5 (NPR) KFLY KEUG KXL AM 750 KHPE KLCC KUGN KKNU KMGE KZEL KKNX KQFE Affiliates of CBS, NBC and ABC also welcome. -

President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 82) at the Gerald R

Scanned from the President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 82) at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDENT GERALD R. FORD PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo .. Day. Yr.) THE WHITE HOUSE MAY 22, 1976 WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME DAY 7:01 a.m. SATURDAY PHONE ~ TIME ." ~ ACTIVITY 0:: 1------.-----1 II In Out 0.. 7:01 The President had breakfast. 7:30 The President went to the doctor's office. 7:35 The President went to the Oval Office. 8:11 The President went to the South Grounds of the White House. 8:11 8:18 The President flew by helicopter from the South Grounds to Andrews AFB, Maryland. For a list of passengers, see APPENDIX "A." 8:16 P The President telephoned Congressman John J. Duncan (R-Tennessee). The call was not completed. EDT PDT 8:26 10:56 The President flew by the "Spirit of '76" from Andrews AFB to Medford-Jackson County Airport, Medford, Oregon. For a list of passengers, see APPENDIX "B." (Actual flying time: 5 hours, 30 minutes) 8:36 8:38 P The President talked with Congressman Duncan. 8:53 P The President telephoned Rita Shire, President Ford Committee (PFC) Campaign Chairman for the 7th District of Kentucky. The call was not completed. 9:19 9:20 P The President talked with Doris Petercheff, PFC Coordinator for the 5th Congressional District of Kentucky. 9: 35 9:37 P The President talked with Ms. Petercheff. 9:40 9:43 R The President talked with Senator Hugh Scott (R-Pennsylvania).