LEATHERHEAD COMMUNITY TEST PITTING (See P2) SURREY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mole Valley Local Plan

APPENDICES 1 INTRODUCTION APPENDICES – The Appendices provide additional background and statistical information to the Local Plan. Where relevant, they will be taken into account in the determination of planning applications. INTRODUCTION MOLEVALLEYLOCALPLAN Appendix 1 2 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREAS (see plan on page 8) APPENDIX 1. INTRODUCTION a broad valley northwards to the Thames. The open, flat valley floor is bounded by gently sloping sides and is set ’The Future of Surrey’s Landscape and Woodlands‘* within a gently undulating landscape. identifies seven regional countryside character areas in Surrey and within these, twenty five county landscape ESHER & EPSOM character areas. In Mole Valley, four of the regional countryside character areas are represented with eleven The area between Bookham and Ashtead, excluding the LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREAS county landscape character areas. These are: valley of the River Mole, lies within this landscape character area. Much of the area is built-up but there are tracts of open undulating countryside and Regional County Landscape extensive wooded areas including Bookham Common Countryside Character Areas and Ashtead Common. The gentle dip slope of the Character Areas North Downs to the south of Bookham and Ashtead provides a broad undulating farming landscape Thames Basin S Esher & Epsom composed of a patchwork of fields and occasional Lowlands S Lower Mole irregular blocks of woodland. Although close to the North Downs S Woldingham, Chaldon built-up areas, this area retains much of its rural & Box Hill agricultural landscape character. It provides a S Mole Gap transition between the densely wooded landscape on top of the North Downs and the built-up areas. -

GUILDFORD - DORKING - REIGATE - REDHILL from 20Th September 2021

32: GUILDFORD - DORKING - REIGATE - REDHILL From 20th September 2021 Monday to Friday Sch H Sch H Guildford, Friary Bus Station, Bay 4 …. 0715 0830 30 1230 1330 1330 1415 1455 1505 1605 1735 Shalford, Railway Station …. 0723 0838 38 1238 1338 1338 1423 1503 1513 1613 1743 Chilworth, Railway Station 0647 C 0728 0843 43 1243 1343 1343 1428 1508 1518 1618 1748 Albury, Drummond Arms 0651 0732 0847 47 1247 1347 1347 1432 1512 1522 1622 1752 Shere, Village Hall 0656 0739 0853 53 1253 1353 1353 1438 1518 1528 1628 1758 Gomshall, The Compasses 0658 0742 0856 56 1256 1356 1356 1441 1521 1531 1631 1801 Abinger Hammer, Clockhouse 0700 0744 0858 then 58 1258 1358 1358 1443 1523 1533 1633 1803 Holmbury St Mary, Royal Oak …. 0752 …. at …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. Abinger Common, Friday Street …. 0757 …. these …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. Wotton, Manor Farm 0704 0802 0902 minutes 02 until 1302 1402 1402 1447 1527 1537 1637 1807 Westcott, Parsonage Lane 0707 0805 0905 past 05 1305 1405 1405 1450 1530 T 1540 1640 1810 Dorking, White Horse (arr) 0716 0814 0911 each 11 1311 1411 1411 1456 1552 1552 1652 1816 Dorking, White Horse (dep) 0716 0817 0915 hour 15 1315 1415 1415 1456 1556 1556 1656 1816 Dorking, Railway Station 0720 0821 0919 19 1319 1419 1419 1500 1600 1600 1700 1819 Brockham, Christ Church 0728 0828 0926 26 1326 1426 1426 1507 1607 1607 1707 1825 R Strood Green, Tynedale Road 0731 0831 0929 29 1329 1429 1429 1510 1610 1610 1710 1827 R Betchworth, Post Office 0737 …. 0935 35 1435 1435 1435 1516 1616 1616 1716 …. -

Kentish Weald

LITTLE CHART PLUCKLEY BRENCHLEY 1639 1626 240 ACRES (ADDITIONS OF /763,1767 680 ACRES 8 /798 OMITTED) APPLEDORE 1628 556 ACRES FIELD PATTERNS IN THE KENTISH WEALD UI LC u nmappad HORSMONDEN. NORTH LAMBERHURST AND WEST GOUDHURST 1675 1175 ACRES SUTTON VALENCE 119 ACRES c1650 WEST PECKHAM &HADLOW 1621 c400 ACRES • F. II. 'educed from orivinals on va-i us scalP5( 7 k0. U 1I IP 3;17 1('r 2; U I2r/P 42*U T 1C/P I;U 27VP 1; 1 /7p T ) . mhe form-1 re re cc&— t'on of woodl and blockc ha c been sta dardised;the trees alotw the field marr'ns hie been exactly conieda-3 on the 7o-cc..onen mar ar mar1n'ts;(1) on Vh c. c'utton vPlence map is a divided fi cld cP11 (-1 in thP ace unt 'five pieces of 1Pnii. THE WALDEN LANDSCAPE IN THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTERS AND ITS ANTECELENTS Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London by John Louis Mnkk Gulley 1960 ABSTRACT This study attempts to describe the historical geography of a confined region, the Weald, before 1650 on the basis of factual research; it is also a methodological experiment, since the results are organised in a consistently retrospective sequence. After defining the region and surveying its regional geography at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the antecedents and origins of various elements in the landscape-woodlands, parks, settlement and field patterns, industry and towns - are sought by retrospective enquiry. At two stages in this sequence the regional geography at a particular period (the early fourteenth century, 1086) is , outlined, so that the interconnections between the different elements in the region should not be forgotten. -

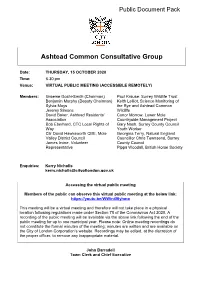

Ashtead Common Consultative Group

Public Document Pack Ashtead Common Consultative Group Date: THURSDAY, 15 OCTOBER 2020 Time: 6.30 pm Venue: VIRTUAL PUBLIC MEETING (ACCESSIBLE REMOTELY) Members: Graeme Doshi-Smith (Chairman) Paul Krause, Surrey Wildlife Trust Benjamin Murphy (Deputy Chairman) Keith Lelliot, Science Monitoring of Sylvia Moys the Rye and Ashtead Common Jeremy Simons Wildlife David Baker, Ashtead Residents’ Conor Morrow, Lower Mole Association Countryside Management Project Bob Eberhard, CTC Local Rights of Gary Nash, Surrey County Council Way Youth Worker Cllr David Hawksworth CBE, Mole Georgina Terry, Natural England Valley District Council Councillor Chris Townsend, Surrey James Irvine, Volunteer County Council Representative Pippa Woodall, British Horse Society Enquiries: Kerry Nicholls [email protected] Accessing the virtual public meeting Members of the public can observe this virtual public meeting at the below link: https://youtu.be/WWin49Iyhmo This meeting will be a virtual meeting and therefore will not take place in a physical location following regulations made under Section 78 of the Coronavirus Act 2020. A recording of the public meeting will be available via the above link following the end of the public meeting for up to one municipal year. Please note: Online meeting recordings do not constitute the formal minutes of the meeting; minutes are written and are available on the City of London Corporation’s website. Recordings may be edited, at the discretion of the proper officer, to remove any inappropriate material. John Barradell Town Clerk and Chief Executive AGENDA 1. WELCOME AND APOLOGIES 2. MEMBERS' DECLARATIONS UNDER THE CODE OF CONDUCT IN RESPECT OF ITEMS ON THE AGENDA 3. -

Abinger Trail

This heritage trail takes in the idyllic village of Abinger Hammer, situated in TILLINGBOURNE TRAILS the heart of the Tillingbourne Valley. Explore the sites of the former mills and historic houses in and around the village, taking in the scenic fields and country roads which run through what was once a booming and thriving Abinger industrial landscape. Length 3.5 km Duration approx. 1.5-2 hours Easy level of difficulty START in the centre of Abinger Hammer village (RH5 6RX). There is a small village car park on the B2126 (Felday Road), next to the bridge, but For more details, download the printable pdf (www.tillingbournetales.co.uk/places/trails) Continue on this path as it veers otherwise parking is very limited (if no parking is available in Abinger, it right, past the side of a house, and may be best to park at Gomshall station and start the walk opposite Old then left, carrying on until you Hatch Farm, adding 1km to the walk). reach Felday Road (*note the road is very busy*). Cross directly over If starting from the centre of the the road and climb the stile to the village and Felday Road (facing footpath opposite. the Post Office and Tea Room), turn left and walk along the A25, with the Tillingbourne Continue along the path, crossing over on your left. START the stream via the bridge, and then as it ascends upwards past Oxmoor Copse on your right. At the fence corner is another stile which you need to cross. The forge at Abinger Hammer was likely situated on the extensive millpond where the ‘Kingfisher’ farm shop and watercress beds are today. -

3382 the London Gazette, 25 May, 1926

3382 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25 MAY, 1926. and Abinger in the rural district of Dorking In the Eural District of Dorking: — as lie to the north of an imaginary line drawn Parish of Dorking Eural: — from the extreme southern boundary of the Bridge from The Eough to Hackhurst said parish of Dorking Eural at Cockshot Downs. Hollow in a straight line due west through Bridge from Evershed's Eough to Upfolds Farm to the western boundary of the Dunley Wood. parish of Abinger and to enable the Company to exercise within the aforesaid parishes and Parish of Wotton: — parts of parishes (hereinafter called " the The bridge carrying the London Eoad added area ") with or without modification, all over the Dorking and Leatherhead branch or some of the powers exerciseable by them of the .Southern Eailway. within their existing area of supply, including The bridge carrying Station Eoad over the powers to break up streets and roads, and the Eeading Branch of the Southern Eail- levying and recovering rates, rents, and way on the east side of Dorking Station. charges for the supply of electricity and Parish of Abinger: — meters and apparatus used in the consumption The roadways and footways on the of electricity, and all the powers that may be bridges over the Beading branch of the acquired by them under the Order. Southern Eailway (1) north of Park Farm 2. To authorise the Company to break up the and (2) south of Dudley Wood and at following streets and parts of streets, includ- Newbarn. ing bridges not repairable by the local authority, and railway, viz: — (D) Eailway, Level Gros&ing:— (A) Main roads : —• Parish of Betchworth: — In the Rural District of Eeigate: — The level crossing of the Southern The main road from G-uildford to Eeigate Eailway at Betchworth Station. -

Biodiversity Working Group SWT Nower Wood EE Centre, Leatherhead Wednesday 15Th January 2020 Minutes 1

Biodiversity Working Group SWT Nower Wood EE Centre, Leatherhead Wednesday 15th January 2020 Minutes 1. Present: Mike Waite (Chair/Surrey Wildlife Trust); Lisa Creaye-Griffin (SNP Director); Rod Shaw (Mole Valley DC); Helen Cocker (Surrey Countryside Partnerships); Stewart Cocker (EEBC); Simon Elson, Rachel Coburn (Surrey CC); Ross Baker/Lynn Whitfield (Surrey Bat Group); Peter Winfield (RBC); Hendryk Jurk (GBC) Georgina Terry (Natural England); Ann Sankey, Susan Gritton (Surrey Botanical Society); Leigh Thornton (Surrey Wildlife Trust); Dave Williams (WSBG/SDG); Jack Thompson (RSPB); Ben Siggery (SWT- minutes). LC-G introduced herself in her new role as Director of the SNP. All welcomed her at the meeting. Apologies: David Watts (R&BBC); Bill Budd (British Dragonfly Society); John Edwards (SCC); Jo Heisse (Environment Agency); Lara Beattie (WoBC); Simon Saville (Butterfly Conservation); Jo Heisse & Francesca Taylor (Environment Agency; Steve Price (SpBC); Isabel Cordwell (RBC), Andrew Jamieson (SWT); Steve Langham (SARG); Alistair Kirk (Surrey Biodiversity Information Centre); Dave Page (EBC) 2. The minutes of the meeting of 11th September 2019 were agreed, see here (on SyNP website). Action 3. Matters Arising: Brockham Limepits. Latest from SCC legal team has established there is free public right of access into the site from the south. Meetings with the landowner disputing this are imminent. SWT will update as required. In the meantime SWT have established a precarious vehicular route in from Box Hill Farm to the west for grazing purposes, and also limited pedestrian access from the north for small volunteer groups. Biodiversity Net Gain; Defra has extended their consultation on the Defra Metric v.2 until the end of February (see here). -

Field Trips for 2018 Contents Click Item to Go Directly to Page Contacts

Number 65 SURREY Skipper Spring/Summer 2018 47 field trips for 2018 Contents click item to go directly to page Contacts......................2 Dates ........................10 Quiz ........................21 Chairman ....................3 Egg Hunts ..................11 Robert Byron ..............22 Annual Report ..............4 Email Appeal ..............12 WCBS ........................23 50th Anniversary ..........5 Field Trips..............13-16 Transect data..........24-29 Steve Wheatley ............6 Branch Website ..........17 iRecord ....................30 Big Butterfly Count ........6 Social Media ..............17 New Members ............31 Malcolm Bridge ............7 Transects ..................18 Membership................32 Surrey Atlas ................7 White-letter Hairstreak 19 Garden Moth Scheme ....32 Small Blue Project ........8 Weather Watch............20 Moths ..................33-35 Oaken Wood ..............10 Photo Show ................21 Back-page Picture ........36 Butterfly Conservation Saving butterflies, moths Surrey & SW London & our environment Surrey Skipper 2 Spring 2018 Branch Committee LINK Committee emails Chair: Simon Saville (first elected 2016) 07572 612722 Conservation Adviser: Ken Willmott (1995) 01372 375773 County Recorder: Harry Clarke (2013) 07773 428935, 01372 453338 Field Trips Organiser: Mike Weller (1997) 01306 882097 Membership Secretary: Ken Owen (2015) 01737 760811 Moth Officer: Paul Wheeler (2006) 01276 856183 Skipper Editor & Publicity Officer: Francis Kelly (2012) 07952 285661, 01483 -

Abinger Sports Card Layout 1

ABINGER SPORTS CLUB ABINGER CRICKET CLUB ABINGER TENNIS CLUB Established 1977 Established 1870 Established 1977 Patron in Memoriam President Patron President Chairman Secretary Treasurer F.C. Triggs (1908 - 2008) J.P.M.H. Evelyn J.P.M.H. Evelyn D. Colebrook TBA R. Thomas TBA 01306 730423 Vice Presidents Vice Presidents ABINGER J.P. Alexander T.J. Coghlan G.D. Locke G. Dunn S. Klimcke M. Robertson Membership liaison: Paul Wildash 01483 202972 T.W. Seymour P.J. Shaw B. Shaw J. Stonehill B. Wakeford Coaching: Linzee Proudfoot 01306 740391 / 07973 256392 P.F. Williams SPORTS CLUB Hon. Life members Key Code for MEMBERS ONLY: 9756 R.B. Arminson M.J.A. Cuthbert G. Dunn Hon. Life members Club Morning - Sundays 11.00am - 1.00pm J.P.M.H. Evelyn Mrs. F. Richardson P. Roberts G. Dunn Mrs. J. Hampshire G.D. Locke Club Evenings (Summer) - Thursdays 6.30pm onwards S.J. Stennett D. Taber P.F. Williams J.E. Richardson G. Staves S.J. Stennett N.M.B. Wood M.G. Woods J. Stonehill ABINGER TABLE TENNIS CLUB Chairman Secretary Treasurer Chairman Hon. Secretary Hon. Treasurer J. Philpin P.J. Evelyn A. Muir R.A. Dunn N. Phillips A.C. Corker Established 1977 01306 883568 07973 288934 01306 730147 01306 730320 01306 730615 01306 731081 Chairman Hon. Secretary Hon. Treasurer Membership Secretary Hon. Fixture Secretary J. Faulkner K. Sutton K. Sutton Miss T. Rowlands J. Philpin 01483 275628 01483 578015 01483 578015 01306 730766 / 07877 182378 01306 883658 / 07570 547627 Evening matches are played Members of Committee Members of Committee September - April in the Guildford Mrs. -

32 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

32 bus time schedule & line map 32 Guildford - Dorking - Strood Green - Redhill View In Website Mode The 32 bus line (Guildford - Dorking - Strood Green - Redhill) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chilworth: 5:12 PM (2) Dorking: 6:05 PM (3) Guildford: 7:00 AM - 5:10 PM (4) Redhill: 6:45 AM - 4:05 PM (5) Strood Green: 7:15 AM - 5:35 PM (6) Wonersh Common: 6:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 32 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 32 bus arriving. Direction: Chilworth 32 bus Time Schedule 83 stops Chilworth Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Redhill Bus Station, Redhill Tuesday Not Operational Palmer Close, Redhill Redstone Hollow, England Wednesday Not Operational Redstone Hollow, Redhill Thursday Not Operational Friday Not Operational Hooley Lane, Earlswood Saturday 5:12 PM Earlswood School, Earlswood St. John's Road, England Earlsbrook Road, Earlswood 32 bus Info Earlswood Railway Station, Earlswood Direction: Chilworth 30 Earlswood Road, England Stops: 83 Trip Duration: 81 min Flying Scud, Earlswood Line Summary: Redhill Bus Station, Redhill, Palmer 45 Woodlands Road, England Close, Redhill, Redstone Hollow, Redhill, Hooley Lane, Earlswood, Earlswood School, Earlswood, Fountain Road, Redhill Earlsbrook Road, Earlswood, Earlswood Railway 73-79 Saint John's, England Station, Earlswood, Flying Scud, Earlswood, Fountain Road, Redhill, Abinger Drive, Mead Vale, The Abinger Drive, Mead Vale Old Oak, Mead Vale, High Trees Road, Reigate, -

Teazle Wood 2014

Teazle Wood 2014 Introduction Lucy Quinnell Following the great successes of 2013 – dramatic improvements to Ponds 1, 2 and 3; the tackling of the litter issues in the wood; fungus surveys leading to the discovery of a species never previously recorded; Teazle Wood’s first ever participation in Heritage Open Days; etc. – we propose that the main focus for activity for 2014 should be the stream networks in and around Teazle Wood. In particular, we would like to help improve the dreadful condition of the Rye Brook (now designated Main River) where it flows along (just outside) the southern boundary of Teazle Wood, close to the main entrance to the woodland. This would tie in with the work carried out upstream at Rye Meadows and on Ashtead Common, and downstream where the Rye flows in to the River Mole – Surrey’s waterways are not in great condition, and are currently the subject of the River Mole Catchment Consultation. With another Friend of Teazle Wood, Caroline Cardew-Smith, I have attended River Mole Catchment Consultation workshops run by Surrey Wildlife Trust at Leatherhead Leisure Centre and the Old Barn Hall in Great Bookham. The Rye formed one of three workshop cases at the Old Barn Hall (April 2014), as did the Fetcham Splash, which is part of the River Mole close to where the Rye meets the Mole. Many groups are interested in the Rye and the Mole in this part of Surrey, and there are clearly many questions that need answers as well as much work to be done if the Rye and this stretch of the Mole are to become the healthy, well-surveyed and well-managed waterways all groups visualize as ‘ideal’. -

T He H Eraldand G Enealogist

A BIBILOGRAPHICAL AND CRITICAL ACCOUNT OF THE THREE EDITIONS OF WATSON’S MEMOIRS OF THE ANCIENT EARLS OF WARREN AND SURREY. _______________ BY JOHN GOUGH NICHOLS, F.S.A. ______________ [Extracted from THE HERALD AND GENEALOGIST.] 1871. WATSON’S EARLS OF WARREN AND SURRY. 193 One of the most remarkable genealogical works produced in England during the last century, both for the purpose and intent of its production and the labor and sumptuousness of its execution, is Watson’s History of the Earls of Warren and Surrey. It is embellished with every illustration, armorial, monumental, and topographical, of which the subject was capable: and further decorated with countless number of ornamental initials and vignettes (generally arabesques of considerable elegance) all impressed from copper plates. The detached engravings, more than fifty in number, are described in the full account which Moule gives of the book in his Bibliotheca Heraldica. pp. 441-445; but it is impossible to estimate the cost which must have been expended on so sumptuous a work. The author, the Rev. John Watson, M.A., F.S.A. had published a History of Halifax (4to. 1775) in which (pp. 523-525) he has given minute details of his own biography down to that period. He was born in 1724 at Lyme cum Hanley, in the parish of Prestbury, Cheshire 1; was elected a Cheshire Fellow of Brazenose 1746; became Perpetual Curate of Ripponden in the parish of Halifax 1754; F.S.A. 1759; Rector of Mouingsby, co. Lincoln, 1766; and Rector of Stockport on the presentation of Sir George Warren, K.B.