Transformation and Defiance in the Art Establishment: Mapping the Exhibitions of the Blk Art Group (1981-1983)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesse Bruton 6 July – 11 September 2016

Ikon Gallery, 1 Oozells Square, Brindleyplace, Birmingham B1 2HS 0121 248 0708 / www.ikon-gallery.org Open Tuesday-Sunday, 11am-5pm / free entry Jesse Bruton 6 July – 11 September 2016 Jesse Bruton, Devil's Bowl (c.1965). Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist. Jesse Bruton is one of the founding artists of Ikon. This exhibition (6 July – 11 September 2016) tells the fascinating story of his artistic development, starting in the 1950s and ending in 1972 when Bruton abandoned painting for painting conservation. Having studied at the College of Art in Birmingham, Bruton was a lecturer there during the early 1960s, following a scholarship year in Spain and a stint of National Service. He went on to teach at the Bath Academy of Art, Corsham, 1966-69. He exhibited in a number of group shows in Birmingham, especially at the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, and had a solo exhibition at Ikon shortly after the gallery opened to the public in 1965, and again in 1967. Like many of his contemporaries, Bruton developed an artistic proposition inspired by landscape. Many of his early paintings were of the Welsh mountains and the Pembrokeshire coast. Alive to the aesthetic possibilities of places he visited, he made vivid painterly translations based on a stringent palette of black and white. They reflected his particular interest “in the way things worked, things like valleys, rock formations and rivers ...” “I wasn’t particularly interested in colour. I wanted to limit the formal language I was using – to work tonally gradating from black to white, leaching out the medium from the paint in order to enhance a variety of textures. -

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

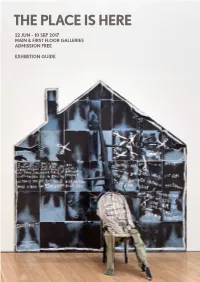

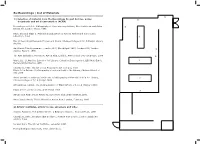

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990 Medium: Lightboxes with Duratran prints Size: 5 parts, total, 190.5 x 121.9cm Collection: Arts Council ACC7/1990 1. Art historical terms and concepts Subject Matter Traditionally portraits depicted named individuals for purposes of commemoration and/or propaganda. In the past black figures were rarely portrayed in Western art unless within group portraits where they were often used as a visual and social foil to the main subject. Rodney adopted the portrait to explore issues around black masculine identity - in this case the stereotype of young black men as a ‘public enemy’. The title ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ comes from the writings of cultural theorist Stuart Hall about media representations of young black men as an ‘icon of danger’, a metaphor for all the ills of society. Rodney said of this Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk work: “I’ve been working for some time on a series…about a black male image, both in the media and black self-perception. I wanted to make a self-portrait [though] I didn’t want to produce a picture with an image of myself in it. It would be far too heroic considering the subject matter. I wanted generic black men, a group of faces that represented in a stereotypical way black man as ‘the other’, a black man as the enemy within the body politic” (1991). Rodney is asking the question: ‘Is this what people see when they see me?’ He has created a kind of ‘everyman’ for every black man, a heterogeneous identity. -

David Prentice 1936 – 2014

DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work - a Selling Retrospective: Part II Autumn 2017 Period, Modern & Contemporary Art DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work - a Selling Retrospective: PART II includes paintings of all periods but also features examples inspired by the Scilly Isles, City of London paintings, the Isle of Skye and The House that Jack Built. Saturday, 7th October 11am - 5pm Sunday, 8th October 11am - 3pm Continues through to 4th November Monday - Saturday 10am - 5pm Sligachan Bridge, Isle of Skye (2012) Watercolour, 23 x 33 ins The Old Dairy Plant · Fosseway Business Park · Stratford Road Moreton-in-Marsh · Gloucestershire · GL56 9NQ Front cover illustration: King’s Reach West (2003) Tel: 01608 652255 · email: [email protected] Oil on canvas, 46 x 56 ins www.johndaviesgallery.com DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work: Part II From both a public perspective and a gallery point of view, range of what are widely regarded as under-appreciated part one of this two-part retrospective for David has been a works of art. distinctly rewarding and illuminating event. First and foremost, the throughput of visitors to the exhibition has been very high. Included in Part ll of A Window on a Life’s Work are five Secondly, the positive reaction of this elevated number of bodies of work – abstract works from the 1960’s and 1970’s observers to David’s work has been significant and voluble. (contrasting to those in Part I), a small group of significant and particularly dynamic paintings derived from the Scilly Isles, a I include in this ‘public’ many of David’s ex-pupils who have good number of the hugely impressive City of London displayed a strong, universal affection for their tutor of fifty canvasses; highly atmospheric works inspired by the Isle of years-ago. -

Phillips, M. the Case of the Absent Artist. a Body Of

The Case of the Absent Artist A Body of Evidence of Mike Phillips 1 The Case for the Defence. On the seventeenth of April 1962 Perry Mason, the legendary defence attorney, faced one of his most pataphysical cases. ‘The Case of the Absent Artist’ (CBS 1962) is an account of a transmogrification that resonates through digital arts practice to this day. The author of the popular comic strip ‘Zingy’, Gabe Philips, transforms from a cartoon- ist to a ‘serious’ painter, bifurcating in the process to become Otto Gervaert. This transformation is only completed when he (both Philips and Gervaert) is/are murdered, the artist(s) remains as a body of evi- dence and a body of work. Mason is faced with the absence left by the transformation of the artist; the absent artist (or artists) defines a new space, not emptiness but a place resonant with potential. The following is a re-investigation of this resonant place left by the artist – Philips/Gervaert and how this transformation of the artist is be- ing enacted with increasing frequency. This manifestation of trans- formation, duality and disappearance is symptomatic of a technologi- cal performativity evident in a series of projects and relationships that have informed the development of frameworks, articulated below as ‘Operating Systems’. As forensic tools these Operating Systems are ‘instruments’ or provocative prototypes that enhance our understand- ing of the world and our impact on it. In the case of the absent artist they probe the space that once held the artist to build a new body of evidence. This body of evidence itself builds on an evolutionary thread that has run through the collaborative work of i-DAT.org. -

Re-Recordings | List of Materials ------9 1) Selection of Material from the Recordings Project Archive, Policy 6 Documents and Art Documentation (ACAA)

Re-Recordings | List of Materials --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 1) Selection of material from the Recordings Project Archive, policy 6 documents and art documentation (ACAA) Recordings: a Select Bibliography of Contemporary African, Afro-Caribbean and Asian 5 British Art. London: INiva, 1996. Race, Sex and Class 5. Multi-Ethnic Education in further, Higher and Community Education, 1983 8 Box of Recordings Research Project and Drafts. Chelsea College of Art & Design Library Archive. Anti-Racist Film Programme. London, GLC, March/April 1985. London GLC/ London 3 Against Racism. 1985. The Arts and Ethnic Minorities: Action Plan. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986 4 Ward, Liz. St.Martin’s School of Art Library: Collection Development, ILEA Muti-Ethnic 1 Review,Winter/Spring 1985 Chambers, Eddie. Blk Art Group Proposal to Art Colleges, 1983 Black Art in Britain: A bibliography of material held in the Library, Chelsea School of Art, 1986 Asian and Afro-Caribbean British art: a Bibliography of Material Held in the Library, 2 Chelsea College of Art & Design,1989. Art Libraries Journal, The Documentation of Black Artists, v.8, no.4 (Winter 1983) Black Arts in London no.50, 4-17 March 1986 7 African and Asian Visual Artists Archive (Flyer and cards) [Bristol],1990. Arts Council Arts & Ethnic Minorities Action Plan. London, February, 1996 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2) Artists’ multiples, artists’ books, ephemera and video Araeen, Rasheed. The Golden Verses: a Billboard Artwork… Artangel Trust, 1990 Chambers, Eddie. Breaking that Bondage: Plotting that Course. London: Black Art Gallery, 1984 Us and ‘Dem, The Storey Institute , Leicester, 1994. Postcard/Virginia Nimarkoh, 1993. Artist Book. The Image Employed, the use of narrative in Black art. -

Re Imaging Donald Rodney

Re imaging Donald Rodney 1 Introduction Reimaging Donald Rodney explores the work of Black British artist Donald Rodney (1961 – 1998). It is the first UK exhibition to examine Rodney’s digital practice, and through new commissions expands on the potential of Rodney’s archive as a resource for challenging our conceptions of cultural, physical and social identity. Donald Rodney was considered to be He developed his artistic skills during one the most significant artists of his prolonged periods of hospitalisation, generation. Mark Sealy, Director of resulting in him regularly missing Autography ABP stated in an online school, due to his sickle cell condition. interview with TATE Britain for their After taking an arts foundation collection of Rodney’s work; course at Bournville School of Art in Birmingham he went on to Nottingham “[Along] with Donald, Keith Piper, Eddie Trent, where he met Keith Piper and Chambers and people like Sonia Boyce, Eddie Chambers. Chambers and Piper Lubaina Himid. Those characters in my espoused the notion of Black Art/Black view are really quite seminal in terms of Power, which derived largely from beginning to create an articulate voice… the USA through black writers and he was really interested in working with activists like Ron Karenga. Becoming Exhibition new media and new technologies. One a prominent member of the Blk Arts of the great tragedies is that he was Group, RRodney highlighted the Reimaging Donald Rodney aims to The new works developed for the becoming very articulate within this sociopolitical condition of Britain in Donald Rodney, from encapsulate the digital embodiment exhibition include doublethink (2015), space around the end of his career”. -

A Missing History: 'The Other Story' Re-Visited

PRESS RELEASE A Missing History: 'The Other Story' re-visited Rasheed Araeen, Sutapa Biswas, Sonia Boyce, Chila Kumari Burman, Avinash Chandra, Uzo Egonu, Lubaina Himid, David Medalla, Keith Piper, Saleem Arif Quadri, A.J. Shemza, F.N. Souza, Aubrey Williams 30th June - 24th July 2010 Private View: Tuesday 29th June, 6.30pm - 9.00pm Aicon Gallery presents 'A Missing History: "The Other Story" re-visited'. This group exhibition re-visits the seminal exhibition 'The Other Story' that closed twenty years ago in June 1990. The show features 13 artists, 11 of whom featured in the original show. 'The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain' curated by Rasheed Araeen, opened at the Hayward Gallery on 29 November 1989. The show's premise was to present artists working in Britain with an African-Caribbean, African or Asian cultural background whose works were ignored by dominant accounts of Modernism. The exhibition subsequently toured to Wolverhampton Art Gallery and finally the Cornerhouse in Manchester where it closed on 10 June 1990. Along with 'Magiciens de la Terre', the 1993 edition of the Whitney Biennial and Documenta XI, 'The Other Story' is one of the key exhibitions that over the last twenty years have impacted on the ways in which a previously closed art world was opened up to issues around post-colonialism, migration, exile, diaspora and globalization. Unsurprisingly each of these exhibitions generated controversy, with heated discussions taking place at the time of each one. 'A Missing History: "The Other Story" re-visited' is an opportunity to look back on these debates at the twenty-year anniversary mark as well as to exhibit the works of 11 of the 24 artists in the original show and two artists who were not in the show. -

E Catalogue, ARAEEN

NEW SCULPTURES BY RASHEED ARAEEN 20–23 MARCH 2019 35 Bury Street London SW1Y 6AY +44 (0)20 7484 7979 [email protected] grosvenorgallery.com Rasheed Araeen (b.1935) is a pioneer of minimalism and a colossal figure in South Asian and Western art. His publications ‘Third Text’ and ‘Black Phoenix’ are seminal, as was ‘The Other Story’, an exhibition organised by Araeen at London’s Hayward Gallery in 1989. A champion of black artists in Britain from the 1960s onwards, his influence and importance within the landscape of 20th century art cannot be overstated. Influenced by his education as a civil engineer, Rasheed Araeen’s abstract sculptures, photographs and paintings feature geometric structures, grids and diagonals. His works explore the concepts of identity and stereotyping of non- Western artists by incorporating religious and cultural symbols from Pakistan, challenging the established Western view of art history. Araeen’s work is currently part of a major touring retrospective. The final leg opens at GARAGE Centre for Contemporary Art, Moscow in early March 2019. The exhibition has previously been displayed at The Van Abbe, Eindhoven, MAMCO, Geneva and BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead. Whilst most are aware of Araeen’s bold use of colour throughout his career, his affinity with black and a monochromatic colour scheme goes back to the early 1960s. His series ‘Hyderabad’ and ‘Before the Departure’ featured sets of black canvases and drawings, where the features of the crowded city peer through the murk. opposite Rasheed Areen Retrospective, Van Abbe Museum, Eindhoven Black Painting No.6 (Before the Departure), 1963 2 3 The 1980s saw the colour take on a new, political meaning in his multi panel installation ‘Tableau Noir, 1987’. -

1 Curriculum Vitae EDDIE CHAMBERS

Curriculum vitae EDDIE CHAMBERS www.eddiechambers.com African Art/African American Art/African Diaspora art history, Field Editor, caa.reviews, (http://www.caareviews.org / http://www.caareviews.org/reviews/2969#.VxlZGaX_R94) appointed August 2014, now serving a second three-year term Member of the editorial board of caa.reviews for a four-year term, from July 1, 2018, to June 30, 2022. Art Monthly Foundation Honorary Patron, (together with Liam Gillick, Hans Haacke, Alfredo Jaar, and Martha Rosler) Appointed June 2018 The University of Texas at Austin Department of Art and Art History 2301 San Jacinto Blvd. Stop D1300 Austin, Texas 78712-1421 EDUCATION Historical and Cultural Studies Department, Goldsmiths College, University of London, (Supervisor, Professor Sarat Maharaj, Internal Examiner, Dr. Carol McKay, External Examiner, Professor Stuart Hall) Black Visual Arts Activity in England 1981-1986: Press and Public Responses, PhD awarded March 31, 1998 Sunderland Polytechnic, Faculty of Art and Design, Fine Art Department, 1980 - 1983. BA (Hons.) Fine Art, 2:1 UT-AUSTIN APPOINTMENT Assistant Professor, Art History, January 2010 – August 2013 Associate Professor, Art History, September 2013 – August 2016 Professor, Art History, September 2016 onwards Inaugural Curatorial Fellow at the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies, Fall Semester 2013/Spring Semester 2014 Assistant Chair, Art History Division, Fall 2015 – Summer 2017, two-year term OTHER TEACHING Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Visiting Professor, Art History department, spring semester 2008, and spring semester and fall semester 2009. 1 Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Visiting Professor, Art History department, spring semester and fall semester, 2005 and fall semester 2006. -

Curriculum Vitae Chila Kumari Burman

! ! Curriculum Vitae Chila Kumari Burman Brought up in Liverpool and educated at the Slade School of Art in London, Chila Kumari Burman has worked experimentally across printmaking, painting, sculpture, photography and film since the mid-1980s. She draws on fine and pop art imagery in intricate multi- layered works which explore Asian femininity and her personal family history, and where Bollywood bling merges with childhood memories. The Bindi Girls are a series of female figures composed almost entirely of colourful and glittery bindis, gems and crystals. Meticulously handcrafted and embellished, they suggest a powerful yet playful femininity. From bindis and other fashion accessories to ice cream cones and ice lolly wrappers, Chila often uses everyday materials in her work, giving new meaning to items which others may see as worthless, cheap or kitsch. Ice Cream has a particular significance in her work and references her childhood in Liverpool where her father, who arrived as an immigrant from India in the 1950s, owned an ice cream van and was a popular figure as he drove around selling ice cream for over thirty years. As well as paying homage to her father, her Ice Cream works evoke the awakening of her own creative spirit when as a child she would help out in the ice cream van and became immersed in a world of colour, flavour and materials. Chila Kumari Burman’s work is held in a number of public and private collections including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Wellcome Trust in London, and the Devi Foundation in New Delhi. -

Mousse 58 R. Araeen

MOUSSE 58 132 R. ARAEEN Sculpture No 2, 1965. Courtesy: Aicon Gallery, New York COUNTLESS (UNTOLD) STORIES RASHEED ARAEEN IN CONVERSATION WITH JENS HOFFMANN In a distinctive career spanning more than five decades, the Pakistani- born, Britain-based artist, writer, publisher, and occasional curator Rasheed Araeen has like no other practitioner radically questioned the art world’s fixation on Western-dominated artistic histories and discours- es. His outspoken critique of power structures and hierarchies, as well as the inherent racism in the art world and the exclusion of large parts of the non-Western art world from general discourse, have made him one of the most essential and provocative voices in the arts. Sculpture No 2, 1965. Courtesy: Aicon Gallery, New York In this conversation, Araeen speaks about his early fascination with the work of Anthony Caro, his thoughts on and involvement with Minimalism, his skepticism toward postcolonial theory, his seminal journal Third Text, his groundbreaking 1989 exhibition The Other Story, and his latest endeavor, the book The Whole Story Art in Postwar Britain, a reassessment of British art history from a non-Western per- spective. Accompanying this conversation is a partial reprint of the first issue of the seminal journalBlack Phoenix, which was founded in 1978 and copublished and coedited by Araeen and Mahmood Jamal, an Urdu poet, artist, and theorist. Black Phoenix aimed at offer- ing a space for modes of thought that contended with Western forms of cultural hegemony. It paved the way toward a more nuanced under- standing of race in Britain. MOUSSE 58 134 R.