Proceedings of the Forteenth Symposium on the Natural History Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marina Status: Open with Exceptions

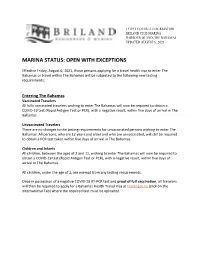

LATEST COVID-19 INFORMATION BRILAND CLUB MARINA HARBOUR ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS UPDATED AUGUST 6, 2021 MARINA STATUS: OPEN WITH EXCEPTIONS Effective Friday, August 6, 2021, those persons applying for a travel health visa to enter The Bahamas or travel within The Bahamas will be subjected to the following new testing requirements: Entering The Bahamas Vaccinated Travelers All fully vaccinated travelers wishing to enter The Bahamas will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. Unvaccinated Travelers There are no changes to the testing requirements for unvaccinated persons wishing to enter The Bahamas. All persons, who are 12 years and older and who are unvaccinated, will still be required to obtain a PCR test taken within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. Children and Infants All children, between the ages of 2 and 11, wishing to enter The Bahamas will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. All children, under the age of 2, are exempt from any testing requirements. Once in possession of a negative COVID-19 RT-PCR test and proof of full vaccination, all travelers will then be required to apply for a Bahamas Health Travel Visa at travel.gov.bs (click on the International Tab) where the required test must be uploaded. LATEST COVID-19 INFORMATION BRILAND CLUB MARINA HARBOUR ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS UPDATED AUGUST 6, 2021 Traveling within The Bahamas Vaccinated Travelers All fully vaccinated travelers wishing to travel within The Bahamas, will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of the travel date from the following islands: New Providence, Grand Bahama, Bimini, Exuma, Abaco and North and South Eleuthera, including Harbour Island. -

AFTER the STORM: WHY ART STILL MATTERS Amanda Coulson Executive Director, NAGB

Refuge. Contents An open call exhibition of Bahamian art following Hurricane Dorian. Publication Design: Ivanna Gaitor Photography: Jackson Petit Copyright: The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) 8. Director’s Foreword by Amanda Coulson © 2020 The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas 16. Curator’s Note by Holly Bynoe West and West Hill Streets Nassau, N.P. 23. Writers: Essays/Poems The Bahamas Tel: (242) 328-5800 75. Artists: Works/Plates Email: [email protected] Website: nagb.org.bs 216. Acknowledgements ISBN: 978-976-8221-16-2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. Cover: Mystery in da Mangroves, 2019 (New Providence) Lemero Wright Acrylic on canvas 48” x 60” Collection of the artist Pages 6–7: Visitor viewing the artwork “Specimen” by Cydne Coleby. 6 7 AFTER THE STORM: WHY ART STILL MATTERS Amanda Coulson Executive Director, NAGB Like everybody on New Providence and across the other islands of our archipelago, all of the there, who watched and imagined their own future within these new climatic landscapes. team members at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) watched and waited with a rock in their bellies and their hearts already broken, as the storm ground slowly past the islands In addition to conceiving this particular show “Refuge,” in order to create space for artists to of Abaco and Grand Bahama. -

Abacos Acklins Andros Berry Islands Bimini Cat Island

ABACOS ACKLINS ANDROS BERRY ISLANDS BIMINI CAT ISLAND CROOKED ISLAND ELEUTHERA EXUMAS HARBOUR ISLAND LONG ISLAND RUM CAY SAN SALVADOR omewhere O UT there, emerald wa- ters guide you to a collection of islands where pink Ssands glow at sunset, where your soul leaps from every windy cliff into the warm, blue ocean below. And when you anchor away in a tiny island cove and know in your heart that you are its sole inhabitant, you have found your island. It happens quietly, sud- denly, out of the blue. I found my island one day, OUT of the blue. OuT of the blue. BIMINI ACKLINS & Fishermen love to tell stories about CROOKED ISLAND the one that got away… but out Miles and miles of glassy water never here in Bimini, most fishermen take deeper than your knees make the home stories and photos of the bonefishermen smile. There’s nothing big one they actually caught! Just out here but a handful of bone- 50 miles off the coast of Miami, fishing lodges, shallow waters and Bimini is synonymous with deep still undeveloped wilderness. Endless sea fishing and the larger-than-life blue vistas and flocks of flaming-pink legend of Hemingway (a frequent flamingos are the well kept secrets Something Borrowed, adventurer in these waters). You’re of these two peculiar little islands, never a stranger very long on this separated only by a narrow passage Something Blue. fisherman’s island full of friendly called “The Going Through.” smiles and record-setting catches. Chester’s Highway Inn A wedding in the Out Islands of the Bahamas is a Resorts World Bimini Bonefish Lodge wedding you will always remember. -

The Birds of Long Island, Bahamas

Wilson Bull., 104(2), 1992, pp. 220-243 THE BIRDS OF LONG ISLAND, BAHAMAS DONALD W. BUDEN ’ ABSTRACT.-ChIe hundred and ten species of birds are recorded from Long Island and adjacent cays, 54 for the first time. No species or subspecies is endemic. Of the 48 probable breeding indigenous species, 23 are land birds, most of which are widely distributed in all terrestrial habitats. The Yellow Warbler (Dendroicapetechia) shows the strongest habitat preference, being nearly confined to mangroves. Nests, eggs, and young are reported for 3 1 species, 19 of them for the first time on Long Island. The White-winged Dove (Zenaidu asiatica) and Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea) are new additions to the list of breeding land birds. The Bahama Mockingbird (Mimus gundluchii)was the most frequently encountered bird during summer 1990, followed closely by the Thick-billed Vireo (Vireo crassirostris).Received I6 May 1991, accepted5 Nov. 1991. The avifauna of Long Island has never been reviewed systematically, the literature consisting mainly of brief and sparsely annotated noncu- mulative lists of species. In nearly all cases, these earlier reports have been based on visits of only one to several days duration covering a very limited area, mainly Clarence Town and vicinity. The present report brings together all available information on the distribution of the birds of Long Island and is based in large measure on my observations through- out the island during 28 April-l 3 May and 6 July-l 2 August 1990 together with unpublished records contributed by other observers. STUDY AREA Long Island is located in the central part of the Bahama archipelago and is the south- easternmost island of any appreciable size on the Great Bahama Bank (Figs. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Coleoptera (Insecta) of the Bahamas

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 4-11-2008 An annotated checklist of the Coleoptera (Insecta) of the Bahamas Robert H. Turnbow Jr. Enterprise, AL Michael C. Thomas Florida State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Turnbow, Robert H. Jr. and Thomas, Michael C., "An annotated checklist of the Coleoptera (Insecta) of the Bahamas" (2008). Insecta Mundi. 347. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/347 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -27)'8% 192(- A Journal of World Insect Systematics %R ERRSXEXIH GLIGOPMWX SJXLI'SPISTXIVE -RWIGXE SJXLI&ELEQEW 6SFIVX,8YVRFS[.V &VSSOZMI['X )RXIVTVMWI%0 1MGLEIP'8LSQEW *PSVMHE7XEXI'SPPIGXMSRSJ%VXLVSTSHW *PSVMHE(ITEVXQIRXSJ%KVMGYPXYVIERH'SRWYQIV7IVZMGIW 43&S\ +EMRIWZMPPI*0 Date of Issue: April 11, 2008 ')28)6 *367=78)1%8-')2831303+=-2'+EMRIWZMPPI*0 6SFIVX,8YVRFS[.VERH1MGLEIP'8LSQEW %RERRSXEXIHGLIGOPMWXSJXLI'SPISTXIVE -RWIGXE SJXLI&ELEQEW -RWIGXE1YRHM 4YFPMWLIHMRF] 'IRXIVJSV7]WXIQEXMG)RXSQSPSK]-RG 43&S\ +EMRIWZMPPI*097% LXXT[[[GIRXIVJSVW]WXIQEXMGIRXSQSPSK]SVK -RWIGXE1YRHMMWENSYVREPTVMQEVMP]HIZSXIHXSMRWIGXW]WXIQEXMGWFYXEVXMGPIWGERFITYFPMWLIHSR -

Assessment of the Effects and Impacts of Hurricane Matthew the Bahamas

AssessmentThe Bahamas of the Effects and Impacts of Hurricane Matthew The Bahamas Oct 6, - 7:00 pm 1 2 3 4 6 7 Centre path of Hurricane Matthew 1 Grand Bahama 2 Abaco 8 5 3 Bimini Islands 4 Berry Islands 12 5 Andros Hurricane force winds (74+ mph) 6 New Providence 9 7 11 Eleuthera 50+ knot winds (58+ mph) 8 Cat Island 9 The Exumas 10 Tropical storm force winds (39+mph) 10 Long Island 11 Rum Cay 14 12 San Salvador 13 Ragged Island 14 Crooked Island 15 Acklins 16 Mayaguna 13 15 16 17 The Inaguas 17 Oct 5, - 1:00 am 1 Hurricane Matthew 2 The Bahamas Assessment of the Effects and Impacts of Hurricane Matthew The Bahamas 3 Hurricane Matthew Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean Omar Bello Mission Coordinator, Affected Population & Fisheries Robert Williams Technical Coordinator, Power & Telecommunications Michael Hendrickson Macroeconomics Food and Agriculture Organization Roberto De Andrade Fisheries Pan American Health Organization Gustavo Mery Health Sector Specialists Andrés Bazo Housing & Water and Sanitation Jeff De Quattro Environment Francisco Ibarra Tourism, Fisheries Blaine Marcano Education Salvador Marconi National Accounts Esteban Ruiz Roads, Ports and Air Inter-American Development Bank Florencia Attademo-Hirt Country Representative Michael Nelson Chief of Operations Marie Edwige Baron Operations Editorial Production Jim De Quattro Editor 4 The Bahamas Contents Contents 5 List of tables 10 List of figures 11 List of acronyms 13 Executive summary 15 Introduction 19 Affected population 21 Housing 21 Health 22 Education 22 Roads, airports, and ports 23 Telecommunications 23 Power 24 Water and sanitation 24 Tourism 24 Fisheries 25 Environment 26 Economics 26 Methodological approach 27 Description of the event 29 Affected population 35 Introduction 35 1. -

Ornithogeography of the Southern Bahamas. Donald W

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 Ornithogeography of the Southern Bahamas. Donald W. Buden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Buden, Donald W., "Ornithogeography of the Southern Bahamas." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3325. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3325 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the Him along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Bimini - a Romantic Long Weekend in the Bahamas 4 Day Itinerary

Bimini - A romantic long weekend in the Bahamas 4 day Itinerary Sudami cruising in Bimini If you’re looking for a romantic getaway, spending a long weekend on a yacht in the Bahamas is just the ticket, with its stunning beaches and crystal clear waters. The Bahamas are perhaps the best kept secret when it comes to yacht charter vacations. From breathtaking white sand beaches to crystal clear waters, to shipwreck snorkeling and dive sites and some of the best fishing in the world, the islands of the Bahamas are simply awe inspiring. Located to the southwest of Grand Bahamas Island is the Bimini chain of islands, best known as being the Bahamas’ best fishing and diving grounds. Because the islands are situated at the edge of a sheerwater cliff on the edge of the Gulf Stream, their coral reefs are teaming with undersea life and the Stream itself serves to bring a variety of monster game fish, wild Atlantic spotted dolphins and sea turtles to its waters. Aerial of Bimini showing deep water on one side, where game fishing is popular It was these islands that also inspired Ernest Hemingway in the 1930s, where he spent much time chasing big game fish and throwing back more than a few rums with the locals. Fountain of youth: Bimini’s mystic Healing Hole in the mangroves Strata Smith Day 1 Make an early crossing from Florida to Bimini, or fly in and meet your yacht. Explore Alice Town, North Bimini on foot or golf cart, sample fresh conch salad, or perhaps head over to South Bimini to visit the Shark Lab, an outpost owned and operated by Dr Samuel H Gruber that researches Bimini’s Lemon sharks. -

Rum Cay and San Salvador Fact Sheet

RUM CAY AND SAN SALVADOR FACT SHEET Rum Cay is one the best kept secrets in The Bahamas. This authentic Out Island gem is prominent for its historical ruins, lush landscape, pink sand beaches and thrilling surf on the island’s north coast. Located just 35 miles away from Rum Cay you’ll find San Salvador, a premier scuba diving destination and well-known historic island where Christopher Columbus may or may not have first made landfall in 1492. This off-the-beaten-path island offers diverse terrain including rolling hills, secluded beaches, salt-water lakes and lively reefs, which make for ideal diving sites. HISTORY Rum Cay was originally named Mamana by the Arawaks, but the present-day name is said to have come about following the discovery of a shipwrecked cargo of rum during the rum-running days of the 1800s. San Salvador’s several name changes are a reflection of its deep historical past. The Lucayan Indians, an indigenous Arawak tribe, initially named the island Guanahani which meant “welcome” in Arawak. However, in 1492, Columbus named it San Salvador or “Holy Savior,” and by the 17th century, British Pirate Captain George Watling took over the island, making it his headquarters and named it Watling Island, after himself. The island retained this name until 1925 when it was once again named San Salvador. ABOUT RUM CAY • Town/Settlement: Port Nelson • SiZe: 30 square miles • Population: Approximately 53 ABOUT SAN SALVADOR • Town/Settlement: Cockburn Town • SiZe: 12 miles long and five miles wide • Population: Approximately 1,000 SAN SALVADOR ACCOMMODATIONS Club Med Columbus Isle – This secluded, all-inclusive and environmentally friendly resort offers a paradise for those seeking a diving or romantic vacation. -

Bahamas Bibliography a List of Citations for Scientific, Engineering and Historical Articles Pertaining to the Bahama Islands

BAHAM AS BIBLIOGRAPHY A LIST OF CITATIONS FOR SCIENTIFIC, ENGINEERING AND HISTORICAL ARTICLES PERTAINING TO THE BAHAMA ISLANDS by CAROL FANG and W. HARRISON SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT NUMBER 56 of the VIRGINIA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 '9 72 BAHAMAS BIBLIOGRAPHY A LIST OF CITATIONS FOR SCIENTIFIC, ENGINEERING AND HISTORICAL ARTICLES PERTAINING TO THE BAHAMA ISLANDS BY CAROL FANG AND W. HARRISON SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT NO. 56 1972 Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 William J. Hargis, Jr. Director TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ARCHAEOLOGY - ANTHROPOLOGY - HISTORY . • • . • . • • . • • 1 BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES . • • . • . • 4 GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES . • • • . • 23 OCEANOGRAPHY AND ENGINEERING . • • • . • . • . • • 38 iii INTRODUCTION Specialized bibliographies are sometimes needed in connection with the research studies being pursued at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. The Bahamas Bibliography arose out of the needs of marine geologists, biologists and physical oceanographers engaged in studies of beaches, fishes and inlet currents in the Bahama Islands. Although the present bibliography may suffer from complete ness, it significantly surpasses in number of citations the only other known bibliography! of like kind. It should be noted that certain of the citations ~ight fit equally well under more than one of the subject headings used for grouping the references. The user would do well, therefore, to check similar headings when searching for references by general subjects. 1Boersma, Anne. 1968. Bibliography on the Bahama Islands. Mass. Inst. Technol. Exp. Astron. Lab. Rep. No. RN-37. 60 p. v ARCHAEOLOGY - ANTHROPOLOGY - HISTORY There are a great number of semi-popular histories and traveller's accounts that deal with the Bahamas and for these the interested reader should refer to Craton. -

Tribune 25 Template V2009

C M C M Y K Y K WEATHER TRY OUR DOUBLE FILET-O-FISH ANY TIME...ANY PLACE, WE’RE #1 HIGH 88F The Tribune LOW 75F T-STORM IN SPOTS BAHAMAS EDITION www.tribune242.com Volume: 105 No.256 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2009 PRICE – 75¢ (Abaco and Grand Bahama $1.25) Choosing CARS FOR SALE, Honour for S E S the right E R T D HELP WANTED I U R S T O ‘SEA WOLF’ N A P I AND REAL ESTATE E Relationships S F SEE WOMAN SECTION BAHAMAS BIGGEST SEE PAGE NINE TRAVOLTA TRIAL: Women charged WEEK TWO ‘Bridgewater’s meeting with Travolta lawyer in pilot murder secretly recorded’ f f FORMER PLP a t Defendants aged 20 and 19 in court s Senator Pleasant e n Bridgewater and u b former premedic i r T Tarino / e Lightbourne Pair also accused of attempted murder k r a lawyer Carlson l C By NATARIO McKENZIE Shurland m Tribune Staff Reporter i yesterday. [email protected] T By NATARIO TWO young women McKENZIE charged with the murder of Tribune Staff Reporter Bahamasair pilot Lionel [email protected] McQueen were arraigned in Magistrate’s Court yesterday. AN attorney for Hollywood celebrity John Travolta Genear McKenzie, 20, of allowed police to set up recording devices in his hotel Warren Street alias “Nettie”, room for a meeting with former PLP Senator Pleasant and Rhonda Knowles, 19, of Bridgewater, it was revealed in court Monday. Winton Estates, alias “Ganja Bridgewater and former ambulance driver Tarino Baby”, have been charged with the murder of McQueen, SEE page 12 29. -

Bahamas 2018 Ports of Entry (REVISED)

Bahamas 2018 Ports of Entry (REVISED) In Spring 2018, Bahamas Customs announced a new list of official ports of entry where you can clear customs, immigration and buy a cruising permit. Our experience is that the official list on the Bahamas Customs website is inaccurate in some places. At some ports listed, customs may not clear general boaters, except under extraordinary circumstances. Conversely, some marinas where customs regularly clears are not included on the website list. In March 2018, Waterway Guide conducted a national survey to find out which ports of entry were actual places to clear in. The list below reflects the results of that survey and serves as our unofficial guide. We have included newly assigned phone numbers. Customs headquarters has reaffirmed that transport fees should not normally be charged and, if so, a receipt must be given. We have learned, however, that when customs has to travel long distances to clear a vessel, voluntary tipping is an accepted practice. Our general advice is to always call a marina or customs well in advance. This list updates pages 44-45 in Waterway Guide’s 2018 Bahamas Edition. ABACO & ABACO CAYS Green Turtle Cay • Customs Office (New Plymouth): 699-4045 Marsh Harbour • Leonard M. Thompson Intl. Airport/Marsh Harbour Bluff House Marina: 365-4247 Airport (MHH): 367-1903 or 699-4021 • Green Turtle Club: 365-4271 • Cherokee Air (FBO): 367-1900 • Green Turtle Government Dock: 699-4045 • Conch Inn Marina (The Moorings): 367-4000 • Leeward Yacht Club Marina: 365-4191 • Abaco Beach Boat Harbour: 367-2158 Sandy Point, South Abaco • Harbour View Marina: 367-3910 • Sandy Point Airport (MYAS): Request prior.