Literary Journals - Sue Waterman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography of Studies of Eighteenth-Century Journalism and the Periodical Press, 1986-2009

Bibliography of Studies of Eighteenth-Century Journalism and the Periodical Press, 1986-2009 This bibliography surveys scholarship published from 1986 to 2009 on journalism, diverse serials (including almanacs), and the periodical press throughout the Europe and the Americas during the "long eighteenth century," approximately 1660-1820. It is most inclusive for the years 1990-2007, in consequence of my compiling studies of that period for Section 1--"Printing and Bibliographical Studies"--of the ECCB: Eighteenth-Century Current Bibliography, until recently known as The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography. It focuses on printed publications, but a few electronic publications have been included. Dissertations and book reviews also are included. For suggestions and corrections, I am indebted to Professor James E. Tierney. In Spring 2003, I learned of many publications, particularly on German periodicals, from Mr. Harold Braem of Hildesheim, who has provided me with titles in his Historische Zeitungen: Privatarchiv der deutschsprachigen Presse des 17.-19. Jahrhunderts. Later, others, such as Marie Mercier-Faivre, Eric Francalanza, Rudj Gorian, and Charles A. Knight, have called attention to errors and overlooked studies. Of course, I am also indebted to many published bibliographies, most especially those by Diana Dixon published in inter-related annual serials: Journal of Newspaper and Periodical History (London, 1984-1994), Studies in Newspaper and Periodical History (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1994-1997), Media History (1999-2002). I have also drawn upon Kim Martin Long's checklists in issues of American Periodicals, and various annual bibliographies dedicated to literature in specific languages, the most useful being MHRA's Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature, with its inclusive chapter on periodicals. -

Feminist Theory, and Much of Women's Culture

The University of Wisconsin System -=-I A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS VOLUME 9, NUMBER 1 SPRING 1989 Published by Susan Searing, Women's Studies Librarian Zi University of Wisconsin System 112A Memorial Library '32 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 22 (608) 262-5754 A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS -- Volume 9. Number 1 S~rlna1989 Periodical literature is the cuttingedge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. A Currwa. of Co- is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis. with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. lt is our hope that Pen- will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to providethe requisite bibliographicinformation shoulda reader wish to subscribe to a joumal or to obtain a particular article at her librw or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues of major feminist journals are reproduced in each issue of -, -, . preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of Ee. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. subscription price(s). 4. Subscription address. -

Library Resources Technical Services

Library Resources FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY & ISSN 0024-2527 Technical Services January 2007 Volume 51, No. 1 Cognitive and Affective Processes in Collection Management Brian Quinn Toward Releasing the Metadata Bottleneck Amanda J. Wilson A Review and Analysis of Library Availability Studies Thomas E. Nisonger The Challenges of Change Shawne D. Miksa The Association for Library Collections & Technical Services 51 ❘ 1 From The Library of Congress Free For 30 days 2 Essential Cataloging & Classification Tools on the Web CATALOGER’S DESKTOP CLASSIFICATION WEB The most widely used cataloging Full-text display of all LC classification documentation resources in an schedules & subject headings. integrated, online system— Updated daily. accessible anywhere. • Find LC/Dewey correlations—Match LC classifica- • Look up a rule in AACR2 and then quickly and easily tion and subject headings to Dewey® classification consult the rule’s LC Rule Interpretation (LCRI). numbers as found in LC cataloging records. Use in • Turn to dozens of cataloging publications and metadata conjunction with OCLC’s WebDewey® service for resource links plus the complete MARC 21 documentation. perfect accuracy. • Find what you need quickly with the enhanced, • Search and navigate across all LC classes or the simplified user interface. complete LC subject headings. Free trial accounts & Free trial accounts & annual subscription prices: annual subscription prices: Visit www.loc.gov/cds/desktop Visit www.loc.gov/cds/classweb For free trial, complete the order form at For free trial, complete the order form at www.loc.gov/cds/desktop/OrderForm.html www.loc.gov/cds/classweb/application.html AACR2 is the joint property of the American Library Association, the Canadian Library Dewey and WebDewey are registered trademarks Association, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals. -

Importance of Periodical Literature in Research

International Journal of Library and Information Studies Vol.8(2) Apr-Jun, 2018 ISSN: 2231-4911 Importance of Periodical Literature in Research P. Madhava Rao Research Scholar Dept. of Library and Information Sciene Sri Venkateswara University Tirupati e-mail Id: [email protected] Prof. V. Pulla Reddy (Retd.) Department of Library and Information Science S.V.University Tirupati – 517502 Andhra Pradesh, India Email : [email protected] Abstract - The current study makes an attempt to know the importance of periodical literature in research. Periodical is a primary source of information. Primary sources of information are the first published records of original research and development or description of new application or new interpretation of an old theme or idea. The literature is generally published as periodical articles since periodicals are the best available sources among the primary communicating media for exchange of scientific results. The importance of periodical publication increases as the necessity for going deep, pinpointed and up-to-date knowledge increased. Periodicals are especially important to scholars because they facilitate what is known as scholarly communication. It is very important to be able to interpret periodical citations accurately. To find periodical articles you must use a periodical index. A periodical index gives you citations to articles that have been published in a specific set of periodicals that cover certain subject area(s). Periodical indexes are available in print and computerized format. Hundreds of periodical indexes exist and it’s important to choose an index appropriate for your research question. Keywords: Periodical literature, Periodical Indexes, Primary sources, Periodical literature, Jourals, Magazines, Trade Journals. -

Science Fiction in the Library, Bibliographies

DOCOMEMT RESUME ED 194 080 IR 008 943 AUTHOR Sullivan, Kathryn TITLE First Contact: Science Fiction in the Library, 1920-1949. POB DATE 77 NOTE 27p. MF01/PCO2. Plus- -Postage.- DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies: Bock Reviews: *Librarians; *Library Acquisition: Library Collections: *Library Material Selection: *Negative Attitudes: policy; *Science Fiction ABSTRACT This report examining the status of science fiction ir libraries. during the 30.!year_period_of.the. genre's infancy discusses past attitudes toward science fiction and policies 'concerning its selection and acquisition. In order to determine how strong an influence reviews would have been on the purchase of science fiction, the book announcements and reviews were surveyed in four selection tools: the American Library Association catalog, Booklist, Library Journal, and Publisher's Weekly. The announcements and reviews were checked on two levels: how many books from Anatomy cf Wonder, a selective bibliography of science fiction books, were included- in the four tools: and what was said about each book. A literature search was also conducted tc discover what librarians were actually saying about science fiction. Tables display the data gathered.and a bibliography is provided. (FM) *********************************************************************** $ Reproductions supplied by EARS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** U f DEPARTMENT OFWEALTH, EOuCATION 4 WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION 40 BEEN REPRO. Isis DOCUMENT HASRECEIVED FROM DUCED EXACTLY AS CO THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORION. O Atom IT POINTS OF VIEWOR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYReims. INSTITUTE OF SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL ...4. EDUCATION POSITION ORPOLICY Cb r".I CM LAJ 10 ICeihr7u Sullivan ti FIRST CONTACT: SCIENCE FICTION IN THE LIBRARY 1920 1949 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS SEEN GRANTED BY Kathryn Sullivan TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." 1. -

Towards an Australian Humanities Digital Archive

TOWARDS AN AUSTRALIAN HUMANITIES DIGITAL ARCHIVE GRAEME TURNER Towards an Australian Humanities Digital Archive Graeme Turner © 2008 Graeme Turner and the Australian Academy of the Humanities Published in 2008 by: The Australian Academy of the Humanities 3 Liversidge St Canberra ACT 2601 Australia [email protected] +61 2 6125 9860 Funding for the scoping study and this publication was provided to the Academy under a special grant from the Australian Government through the then Department of Education, Science and Training. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government, its Ministers or DEST’s successor Departments. Research assistant: Lesley Pruitt Project manager and editor: John Byron Thanks are due for assistance with the administration of the study to: • John Shipp, University Librarian, University of Sydney • Anne-Marie Lansdown, General Manager, Research Infrastructure Branch, Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research • Sarah Howard, Phoebe Garrett and Christina Parolin of the Academy Secretariat Cover image: Gateway Arch, St. Louis, Missouri, USA; courtesy of John Byron. THE AUSTRALIAN ACADEMY OF THE HUMANITIES TOWARDS AN AUSTRALIAN HUMANITIES DIGITAL ARCHIVE A REPORT ON A SCOPING STUDY FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A NATIONAL DIGITAL RESEARCH RESOURCE FOR THE HUMANITIES PREPARED BY PROFESSOR GRAEME TURNER FAHA WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF LESLEY PRUITT SEPTEMBER 2008 PROFESSOR GRAEME TURNER FAHA is an ARC Federation Fellow, Professor of Cultural Studies, and Director of the Centre for Critical and Cultural Studies at the University of Queensland. He is one of the key figures in the development of cultural and media studies in Australia and has an outstanding international reputation in the field. -

The Handbook to Literary Research

The Handbook to Literary Research Edited by Delia da Sousa Correa and W.R. Owens The Handbook to Literary Research is a practical guide for students embarking on postgraduate work in Literary Studies. It introduces and explains research techniques, methodologies and approaches to information resources, paying careful attention to the differences between countries and institutions, and providing a range of key examples. This fully updated second edition is divided into five sections which cover: • Tools of the trade – a brand new chapter outlining how to make the most of literary resources; • Textual scholarship and book history – explains key concepts and varia- tions in editing, publishing and bibliography; • Issues and approaches in literary research – presents a critical overview of theoretical approaches essential to literary studies; • The dissertation – demonstrates how to approach, plan and write this important research exercise; • Glossary – provides comprehensive explanations of key terms, and a checklist of resources. Packed with useful tips and exercises and written by scholars with extensive experience as teachers and researchers in the field, this volume is the ideal handbook for those beginning postgraduate research in literature. Delia da Sousa Correa is Senior Lecturer in English at The Open University, UK. W.R. Owens is Professor of English Literature at The Open University, UK. Contributors: Susan Bassnett, Delia da Sousa Correa, Simon Eliot, Suman Gupta, Sara Haslam, David Johnson, M.A. Katritzky, Derek Neale, W.R. Owens, and Shafquat Towheed. The Handbook to Literary Research Edited by Delia da Sousa Correa and W.R. Owens First published 1998 by Routledge, written and produced by The Open University This edition 2010 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. -

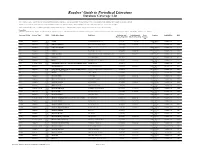

Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature Database Coverage List

Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature Database Coverage List "Core" coverage refers to sources which are indexed and abstracted in their entirety (i.e. cover to cover), while "Priority" coverage refers to sources which include only those articles which are relevant to the field. This title list does not represent the Selective content found in this database. The Selective content is chosen from thousands of titles containing articles that are relevant to this subject. *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Coverage Policy Source Type ISSN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Peer- Country Availability* MID Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Review ed Priority Magazine 0163- 50 Plus Trusted Media Brands, Inc. 01/01/1983 11/01/1988 United States of Available Now 50P 2027 America Priority Magazine 1548- AARP the Magazine. Journal Collection (H.W. Wilson) 05/01/2003 11/01/2011 Available Now D9FN 2014 Core Magazine 1548- AARP: The Magazine AARP 07/01/2003 United States of Available Now QEA 2014 America Core Magazine 1041- Ad Astra National Space Society 01/01/1989 03/31/2020 United States of Available Now ADS 102X America Core Magazine 0955- Adults Learning National Institute of Adult Continuing Education 01/01/1995 04/30/2015 United Kingdom Available Now ALG 2308 Core Magazine 0001- Advocate Here Publishing Inc. -

Download This PDF File

GLORIA S. CLINE College & Research Libraries: Its First Forty Years College & Research Libraries began publication in December 1939. This study examines the changes that occurred in its publication and citation pat terns during the forty years from 1939 through 1979. Data are generally de scribed in terms of eight five-year periods, and the findings of this study are compared with the results of similar studies of various subject literatures. An overall trend toward greater adherence to the norms of scholarly publication in other disciplines was observed. CoLLEGE & RESEARCH LIBRARIES (C&RL) (7) seek to stimulate research and experimentation marked its fortieth year of continuous publi for the improvement of the service and publish cation in December 1979. Widely recognized the results; and as a leader in the field, C&RL has ranked for (8) help to develop the A.C.R.L. into a strong and many years among the top ten library peri mature professional organization. 1 odicals in circulation. Its success is primarily Certainly most, if not all, of these purposes due to the fact that throughout the years it have been adequately served b.y C&RL. Katz has not strayed from its originally stated pur attested to its high quality by stating, ''In poses, which were to: many ways the best of the American Library (1) serve as the official medium of communication Association publications, this is profession between the association and its subsections and ally edited and contains articles and features their members; not only of interest to college and university (2) make available selected articles presented at libraries, but to anyone dealing with the conventions at which college and research li problem of bibliography, cataloging, acqui brarians gather, and publish other profession sitions, and the whole range of professional ally significant articles; librarianship. -

Benjamin G. Carter. Periodical Literature's Place in Young Adult

Benjamin G. Carter. Periodical Literature’s Place in Young Adult Collections: A Collection Analysis and Best Practices Evaluation of Public Libraries in the Triangle Region of North Carolina. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. April, 2006. 31 pages. Advisor: Brian Sturm The purpose of this research was to analyze the periodical collections of public libraries in the Triangle region of North Carolina in terms of young adult titles. Research questions targeted how public librarians provide their young adult patrons with access to periodical collections, address access to periodicals available through the Internet and develop periodical collections in response to research findings on young adult reading. Collections were evaluated in terms of collection policies, placement, reference to other collections, and content. While the research revealed that collections varied in terms of responses to several of the research concerns, the collections showed some consistency in terms of collection policy and response to research findings. Headings: Young Adults’ Periodicals Collection Development/Evaluation Public Libraries/North Carolina Periodical Literature’s Place in Young Adult Collections: A Collection Analysis and Best Practices Evaluation of Public Libraries In the Triangle Region of North Carolina by Benjamin G. Carter A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina April 2006 Approved by _______________________________________ Brian Sturm 1 Introduction For many years, researchers in the fields of library science, education and literacy have studied the reading behavior of young adults. -

Bias in Publishing? Gender Trends in Academic Library and Information Science Monograph Publications

Bias in Publishing? Gender Trends in Academic Library and Information Science Monograph Publications Ngoc-Yen Tran and Erin Nevius* Introduction For academic librarians, especially those in tenure-track positions, publishing is a necessity for tenure and pro- motion. While librarians and other information professionals publish in a number of formats, the publication of a scholarly monograph is undoubtably one of the highest levels of achievement and generally well regarded in the tenure and promotion process. As librarians, we understand that the monograph publication process and monograph publishers themselves can be skewed toward particular viewpoints and that these biases can limit the topics and types of items that are published, as well as who gets published. Although a lot of literature has been completed on gender biases in academic publishing, not many have examined monograph publications and none have looked specifically at library and information science (LIS) monographs. This study seeks to fill that gap through a critical look at the publication trends of academic LIS monographs, and more specifically, the gender of creators (authors and editors). The study addresses the following questions: • Is there a gender gap in LIS scholarly monograph publishing? If so, what does it look like? • How does gender affect co-creatorship (co-authored or co-edited works) in LIS scholarly monograph publishing? • Does gender have an effect on the topics published in LIS scholarly monograph publishing? Literature Review Gender and Creatorship Studies on the genders of creators in academic monograph publishing are extremely limited, but they all indicate that women lag behind men as creators of books. -

Remediating the Past: Doing “Periodical Studies” in the Digital Era Maria Dicenzo Wilfrid Laurier University

Remediating the Past: Doing “Periodical Studies” in the Digital Era Maria DiCenzo Wilfrid Laurier University Every revolution in communication technology–from papyrus to the printing press to Twitter–is as much an opportunity to be drawn away from something as it is be drawn toward something. And yet, as we embrace technology’s gifts, we usually fail to consider what we’re giving up in the process. Michael Harris The End of Absence n his recent award-winning book, The End of Absence, Canadian Ijournalist Michael Harris ponders the implications of the digital age from the perspective of the generation that has known life before and after the advent of the Internet, asking fundamental questions about what is lost in the world of constant connection. As I consider recent developments and debates in periodical research, it seems that a similar divide between the pre- and postdigital worlds has manifested itself. This is not a generational divide in the limited sense of age; instead, it is related to the formation of academic fields and the impact of the large-scale digitization of newspa- ESC 41.1 (March 2015): 19–39 pers, periodicals, and magazines on approaches to scholarship.1 Assess- ments of that impact vary depending not just on when but also on why one has come to these media. The archival materials, once difficult to access, Maria DiCenzo is now seem all too available, creating (with the aid of computational tools) a Professor of English range of new opportunities for researchers and students. Methodological at Wilfrid Laurier shifts are redefining what it means to “read” periodicals.