Study to Determine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Sanford…Errrr, Mount Jarvis. Wait, What?? Mount Who?? It Was Roughly Around Thanksgiving 2016 and the Time Had Come Fo

Mount Sanford…errrr, Mount Jarvis. Wait, what?? Mount Who?? It was roughly around Thanksgiving 2016 and the time had come for me to book my next IMG adventure. With two young children at home and no family close by, I had settled into a routine of doing a big climb every other year. This year was a bit different, as I normally book my major climbs around September for an April or May departure the following year. However, due to a Mt. Blackburn (Alaska) trip falling through, I had to book another expedition. In 2015, I was on an IMG team that summitted Mt. Bona from the north side, not the original plan (jot that down – this will become a theme in Alaska), and really enjoyed the solitude, adventure, physical challenge, small team, and lack of schedule the Wrangell & St Elias Mountains had to offer. So, I hopped on IMG’s website, checked out the scheduled Alaskan climb for 2017, which was Mt. Sanford, and peppered George with my typical questions. Everything lined up, so I completed the pile of paperwork (do I really have to sign another waiver?!?), sent in my deposit (still no AMEX, ugh…), set my training schedule, and started Googling trip reports about Mt. Sanford. Little did I know that READING about Mt. Sanford was the closest I would ever get to it! Pulling from my previous Alaskan climbing experience, I was better prepared for this trip than for Mt Bona in 2015. Due to our bush pilot’s inability to safely land us on the south side of Bona two years prior, we flew up, around, and over the mountain and landed on the north side. -

North America Summary, 1968

240 CLIMBS A~D REGIONAL ?\OTES North America Summary, 1968. Climbing activity in both Alaska and Canada subsided mar kedly from the peak in 1967 when both regions were celebrating their centen nials. The lessened activity seems also to have spread to other sections too for new routes and first ascents were considerably fewer. In Alaska probably the outstanding climb from the standpoint of difficulty was the fourth ascent of Mount Foraker, where a four-man party (Warren Bleser, Alex Birtulis, Hans Baer, Peter Williams) opened a new route up the central rib of the South face. Late in June this party flew in from Talkeetna to the Lacuna glacier. By 11 July they had established their Base Camp at the foot of the South face and started up the rib. This involved 10,000 ft of ice and rotten rock at an angle of 65°. In the next two weeks three camps were estab lished, the highest at 13,000 ft. Here, it was decided to make an all-out push for the summit. On 24 July two of the climbers started ahead to prepare a route. In twenty-eight hours of steady going they finally reached a suitable spot for a bivouac. The other two men who started long after them reached the same place in ten hours of steady going utilising the steps, fixed ropes and pitons left by the first party. After a night in the bivouac, the two groups then contin ued together and reached the summit, 17,300 ft, on 25 July. They were forced to bivouac another night on the return before reaching their high camp. -

Wrangell-St. Elias Alaska

Wrangell - St. Elias National Park Service National Park and National Preserve U.S. Department of the Interior Wrangell-St. Elias Alaska The wildness of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation vest harbor seals, which feed on fish and In late summer, black and brown bears, drawn and Preserve is uncompromising, its geography Act (ANILCA) of 1980 allows the subsistence marine invertebrates. These species and many by ripening soapberries, frequent the forests awe-inspiring. Mount Wrangell, namesake of harvest of wildlife within the park, and preserve more are key foods in the subsistence diet of and gravel bars. Human history here is ancient one of the park's four mountain ranges, is an and sport hunting only in the preserve. Hunters the Ahtna and Upper Tanana Athabaskans, and relatively sparse, and has left a light imprint active volcano. Hundreds of glaciers and ice find Dall's sheep, the park's most numerous Eyak, and Tlingit peoples. Local, non-Native on the immense landscape. Even where people fields form in the high peaks, then melt into riv large mammal, on mountain slopes where they people also share in the bounty. continue to hunt, fish, and trap, most animal, ers and streams that drain to the Gulf of Alaska browse sedges, grasses, and forbs. Sockeye, Chi fish, and plant populations are healthy and self and the Bering Sea. Ice is a bridge that connects nook, and Coho salmon spawn in area lakes and Long, dark winters and brief, lush summers lend regulati ng. For the species who call Wrangell the park's geographically isolated areas. -

The Glenn Highway EMBODIES ALL SIX QUALITIES of a SCENIC BYWAY

The Glenn Highway EMBODIES ALL SIX QUALITIES OF A SCENIC BYWAY. Scenic Historic Cultural Natural Recreational Archaeological This resource This resource Evidence and Those features of Outdoor Those offers a heightened encompasses expressions of the the visual recreational characteristics of visual experience legacies of the past customs or environment that activities are the scenic byways derived from the that are distinctly traditions of a are in a relatively directly associated corridor that are view of natural associated with distinct group of undisturbed state. with and physical evidence and man made physical elements people. Cultural These features dependent upon of historic or elements of the of the landscape, features include, predate the arrival the natural and prehistoric human visual environment whether natural or but are not limited of human cultural elements life or activity that of the scenic man made, that to crafts, music, populations and of the corridor’s are visible and byway corridor. are of such dance, rituals, may include landscape. capable of being The characteristics significance that festivals, speech, geological The recreational inventoried and of the landscape they educate the food, special formations, fossils, activities provide interpreted. The are strikingly viewer and stir an events, vernacular landform, water opportunities for scenic byway distinct and offer a appreciation of the architecture, etc. bodies, vegetation, active and passive corridor’s pleasing and most past. The historic and are currently and wildlife. There recreational archaeological memorable visual elements reflect practiced. The may be evidence of experiences. They interest, as experience. All the actions of cultural qualities of human activity but include, but are not identified through elements of the people and may the corridor could the natural features limited to downhill ruins, artifacts, landscape – include buildings, highlight one or reveal minimal skiing, rafting, structural remains landform, water, settlement more significant disturbances. -

Along the Altsetnaey Nalcine Trail

Along the Ałts’e’tnaey- Nal’cine Trail Historical Narratives, Historical Places by William E. Simeone Foreword by Evelyn Beeter and Barbara Cellarius Along the Ałts’e’ tnaey-Nal’cine Trail: Historical Narratives, Historical Places Produced by Mount Sanford Tribal Consortium, 2014 This project is supported in part through a cooperative agreement with Wrangell- St. Elias National Park and Preserve. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. Front cover: Nabesna Road and the Nutzotin Mountains. Photo by Wilson Justin. Cover and text design by Paula Elmes, ImageCraft Publications & Design Contents Foreword. 2 Introduction . 4 Background . 6 Upper Copper River Places . 16 Tanada Creek Drainage . 20 Jack Creek Drainage . 36 Platinum Creek Drainage . 42 Nabesna River . 49 Pickerel Lake . 58 Chisana River . 60 White River . 68 Conclusion . 70 Epilogue . 72 Acknowledgements . 75 Appendix A: Boundaries of Upper Ahtna Territory . 76 Appendix B: U.S. Census 1920 and 1930 for Batzulnetas, Chistochina, and Cooper Creek (Upper Nabesna) . 78 References Cited . 82 1 Foreword ENCOMPASSING MORE THAN 13 MILLION ACRES OF LAND and some of the highest peaks on North America, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve is the largest con- servation unit managed by the National Park Service. Given the park’s size and its location in Alaska, many visitors view it as an uninhabited wilderness. Yet to Athabascan and Tlingit people, much of the park is home—a cultural landscape within which they have hunted, trapped, fished, gathered, and lived for generations, a landscape crisscrossed with networks of trails and travel routes. -

Richardson Highway Road Log

Richardson Highway Road Log Mile by Mile Description of the Richardson Highway from Fairbanks to Valdez Richardson Highway Highway The Richardson Highway is Alaska’s oldest highway. mile 364 Fairbanks. In 1898 a trail was pushed from Valdez to Eagle in the mile 360.6 Parks Highway to Denali Park, bypass via Interior of Alaska. Residents had requested money the Mitchell Expressway. from Congress to improve the trail but by the time ap- mile 359.7 Business Route. Leads to Cushman St. proval came through, the gold production in the Eagle and downtown Fairbanks. area had declined. The funds were used instead to improve the Fairbanks portion because of the Felix mile 357 Badger Road is a 12 mile loop which rejoins Pedro find in Fairbanks. Major Wilds P. Richardson the Richardson Highway at mile 349.5. worked to upgrade the trail to a wagon road in 1910 mile 349.5 North Pole Alaska. after the Fairbanks gold rush. It was made suitable for mile 349.5 Badger Road is a 12 mile loop which re- vehicles in the 1920s and paved in 1957. joins the Richardson Highway at mile 357. The Richardson connects Valdez (mile 0) and Fair- mile 346.7 Laurance Road. Chena Lake Recreation banks (mile 364). The drive will take you through the Area. 86 campsites with bathrooms and dump station. spectacular and narrow Keystone Canyon and across Boat launch and picnic area, designated swimming the Thompson Pass where you will find Worthington area and rental of canoes, kayaks and row boats. Vol- Glacier, one of the few glaciers in the world that you leyball and basketball courts and playground. -

Shining Mountains, Nameless Valleys: Alaska and the Yukon Terris Moore and Kenneth Andrasko

ALASKA AND THE YUKON contemplate Bonington and his party edging their way up the S face of Annapurna. In general, mountain literature is rich and varied within the bounds of a subject that tends to be esoteric. It is not easy to transpose great actions into good, let alone great literature-the repetitive nature of the Expedition Book demonstrates this very well and it may well be a declining genre for this reason. Looking to the future a more subtle and complex approach may be necessary to to give a fresh impetus to mountain literature which so far has not thrown up a Master of towering and universal appeal. Perhaps a future generation will provide us with a mountaineer who can combine the technical, literary and scientific skills to write as none before him. But that is something we must leave to time-'Time, which is the author of authors'. Shining mountains, nameless valleys: Alaska and the Yukon Terris Moore and Kenneth Andrasko The world's first scientific expedition, sent out by Peter the Great-having already proved by coasting around the E tip of Siberia that Asia must be separated from unseen America-is now, July, 1741, in the midst of its second sea voyage of exploration. In lower latitudes this time, the increasing log of sea miles from distant Petropavlovsk 6 weeks behind them, stirs Com mander Vitus Bering and his 2 ship captains, Sven Waxell of the 'St. Peter' and Alexei Chirikov of the 'St Paul', to keen eagerness for a landfall of the completely unexplored N American coast, somewhere ahead. -

Ahtna Tribal Energy Planning and Technical Assistance Project (ATEPTAP) US Dept

Ahtna Tribal Energy Planning and Technical Assistance Project (ATEPTAP) US Dept. of Energy- Office of Indian Energy Grant Bruce Cain, Director of Program Development Ahtna Inter-Tribal Resource Commission [email protected] Jason Hoke, Executive Director Copper Valley Development Association [email protected] www.coppervalley.org 907-259-5056 OVERVIEW • Introduction • About the Ahtna Region and Need • About the Ahtna Intertribal Resource Commission (AITRC) • ATEPTAP Project Goals and Objectives • Project Work and Success in the first Year • Outreach and Collaborations • Expanded Opportunities Identified (Intertie) • Summary The Ahtna Traditional Use Territory – Land and Resources The Ahtna Region is approximately 45,000 square miles of land (28,700,000 acres) The size of New York. Ahtna’s total ANCSA land entitlement is 1.77 million acres – 1.53 million conveyed • 5 mountain ranges • 2 National Parks: Wrangell-St. Elias & Denali National Parks • Chugach National Forest • Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge • The Copper River watershed is the 4th largest in Alaska • Every species of Alaska fish represented • 11 salmon runs • Five major highways (500+ miles state road) • Abundant wildlife • Strong Ahtna Culture Ahtna Intertribal Resource Commission Ahtna Traditional Use Teritory- Demographics • There are eight federally recognized tribes in the region; Cantwell, Mentasta, Cheesh’na, Gakona, Gulkana, Tazlina, Kluti-Kaah and Chitina. • Population for the Ahtna Territory is 3,682 (2010 Census Data) – 890 Tribal Members in the 8 villages – 1,512 The total population (all ethnicity) for these Villages • Median household income for these villages ranges from: $13,802 Chitina to $104,375 in Gakona. • Outmigration. School enrollment (CRSD) went from 800 to less than 400 since 2000 • Major employment Health Care, Pipeline Maintenance, Tribal, State and Federal Government. -

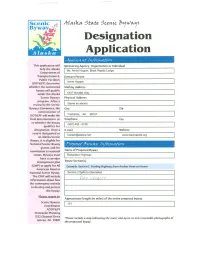

Application /H Ltc-Ant in Pjjt,-,Aftc7n This Application Will Sponsoring Agency, Organization Or Individual Help the Alaska Department of I Ms

- --_u------------ ktA-fk.A- :5tA-te- :5ee-aie ?>1fWA-1f5 Designation Application /h ltC-ant In PJJt,-,aftC7n This application will Sponsoring Agency, Organization or Individual help the Alaska Department of I Ms. Annie Hopper, Black Rapids Lodge Transportation B.. Contact Person Public Facilities (DOTB..PF)determine I Annie Hopper whether the nominated Mailing Address byway willqualify under the Alaska I 1307 WindfallWay Scenic Byways Physical Address program. After a review by the Scenic I (sameas above) BywaysCommittee, the City Zip commissioner of DOTB..PFwill make the I Fairbanks, AK 99707 final determination as Telephone Fax to whether the byway qualifies for I (907) 455 -6158 designation. Once a E-mail Website road is designated as www.blackrapids.org an Alaska Scenic I [email protected] Byway,it is eligible for National Scenic Byway ;PrC7 C7fet(l>tjwa In prf1,-,attC7n grants, and for nomination to national Name of Proposed Byway status. Byways must have a corridor I RichardsonHighway management plan Route Section(s) (CMP)to apply for All Example: Section 1:Sterling Highway from Anchor Point to Homer American Road or Section2 D toGlennallen National Scenic Byway. The CMPwill include FtJI!7 t;t:..E£l.."V information about how the community intends to develop and protect the byway. please return to: Approximate length (in miles) of the entire proposed byway Scenic Byways Coordinator 1151 ADOTB..PF Statewide Planning 3132 Channel Drive *Please include a map indicating the route, and up to six non-returnable photographs of Juneau, AK 99801 the propossed byway. Jfttn:tftC c:Lua!t'ttef he Bywaycan be designated underone or moreof the six "intrinsicqua(ities"defined bythe Federa( HighwayAdministration.P(ease indicatewhich of these qua(itiesare mostapp(jcab(efor the proposed Tbywaydesignation. -

MOUNT Mckinley NATIONAL PARK

MOUNT McKINLEY NATIONAL PARK UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Mount McKinley [ALASKA] National Park United States Department of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammercr, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1937 DO YOU KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS? ACADIA, MAINE.—Combination oi MAMMOTH CAVE, KY.—Interesting mountain and seacoast scenery. Estab caverns, including spectacular onyx cave lished 1919; 24.08 square miles. formation. Established for protection 1936; 38.34 square miles. BRYCE CANYON, UTAH.—Canyons filled with exquisitely colored pinnacles. MESA VERDE, COLO.—Most notable Established 1928; 55.06 square miles. cliff dwellings in United States. Estab lished 1906; 80.21 square miles. CARLSBAD CAVERNS, N. MEX.— Beautifully decorated limestone caverns MOUNT McKINLEY, ALASKA.— believed largest yet discovered. Estab Highest mountain in North America. lished 1930; 15.56 square miles. Established 1917; 3,030.46 square miles. CRATER LAKE, OREG— Astonish MOUNT RAINIER, WASH.—Largest ingly beautiful lake in crater of extinct accessible single-peak glacier system. volcano. Established 1902; 250.52 Third highest mountain in United square miles. States outside Alaska. Established 1899; 377.78 square miles. GENERAL GRANT, CALIF.—Cele brated General Grant Tree and grove PLATT, OKLA.—Sulphur and other of Big Trees. Established 1890; 3.96 springs. Established 1902; 1.33 square square miles. miles. GLACIER, MONT.—Unsurpassed al ROCKY MOUNTAIN, COLO.—Peaks pine scenery; 200 lakes; 60 glaciers. from 11,000 to 14,255 feet in heart of Established 1910; 1,533.88 square miles. Rockies. Established 1915; 405.33 square miles. GRAND CANYON, ARIZ.—World's greatest example of erosion. -

NAZEWNICTWO GEOGRAFICZNE ŚWIATA Ameryka Australia I Oceania

KOMISJA STANDARYZACJI NAZW GEOGRAFICZNYCH POZA GRANICAMI POLSKI przy Głównym Geodecie Kraju NAZEWNICTWO GEOGRAFICZNE ŚWIATA Zeszyt 1 Ameryka Australia i Oceania GŁÓWNY URZĄD GEODEZJI I KARTOGRAFII Warszawa 2004 KOMISJA STANDARYZACJI NAZW GEOGRAFICZNYCH POZA GRANICAMI POLSKI przy Głównym Geodecie Kraju Maksymilian Skotnicki (przewodniczący), Ewa Wolnicz-Pawłowska (zastępca przewodniczącego), Izabella Krauze-Tomczyk (sekretarz); członkowie: Stanisław Alexandrowicz, Andrzej Czerny, Janusz Danecki, Janusz Gołaski, Romuald Huszcza, Sabina Kacieszczenko, Dariusz Kalisiewicz, Artur Karp, Ryszard Król, Marek Makowski, Andrzej Markowski, Jerzy Ostrowski, Henryk Skotarczyk, Andrzej Pisowicz, Bogumiła Więcław, Mariusz Woźniak, Bogusław R. Zagórski, Maciej Zych Opracowanie Bartosz Fabiszewski, Katarzyna Peńsko-Skoczylas, Maksymilian Skotnicki, Maciej Zych Opracowanie redakcyjne Izabella Krauze-Tomczyk, Jerzy Ostrowski, Maksymilian Skotnicki, Maciej Zych Projekt okładki Agnieszka Kijowska © Copyright by Główny Geodeta Kraju ISBN 83-239-7552-3 Skład komputerowy i druk Instytut Geodezji i Kartografii, Warszawa Spis treści Od Wydawcy ..................................................................................................................... 7 Przedmowa ........................................................................................................................ 9 Wprowadzenie ................................................................................................................... 11 Część 1. AMERYKA ANGUILLA ..................................................................................................................... -

At Work in the Wrangells: a Photographic History, 1895-1966 Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN-10: 0-9907252-6-X ISBN-13: 978-0-9907252-6-8

At Work in the Wrangells A Photographic History, 1895-1966 Katherine J. Ringsmuth Our mission is to identify, evaluate and preserve the cultural resources of the park areas and to bring an understanding of these resources to the public. Congress has mandated that we preserve these resources because they are important components of our national and personal identity. Published by the United States Department of the Interior through the Government Printing Office National Park Service Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve At Work in the Wrangells: A Photographic History, 1895-1966 Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN-10: 0-9907252-6-X ISBN-13: 978-0-9907252-6-8 2016 Front Cover: 1950 Copper River Survey, surveyors. Courtesy of the Cordova Historical Museum, 02-40-10. Back Cover: “80 lbs. Packs.” WRST History Files, “Ahtna” Folder, 213. Original photo is located in the Miles Brothers Collection, Valdez Museum, 916. At Work in the Wrangells A Photographic History, 1895-1966 Katherine J. Ringsmuth Horse Creek Mary. WRST History Files, “Ahtna” Folder. Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................vii Acknowledgments .................................................................................................xi Introduction: The Nature of Work .........................................................................1 Chapter One: Subsistence Lifeways ....................................................................19 Chapter Two: Mining