Notable Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dangerous Summer

theHemingway newsletter Publication of The Hemingway Society | No. 73 | 2021 As the Pandemic Ends Yet the Wyoming/Montana Conference Remains Postponed Until Lynda M. Zwinger, editor 2022 the Hemingway Society of the Arizona Quarterly, as well as acquisitions editors Programs a Second Straight Aurora Bell (the University of Summer of Online Webinars.… South Carolina Press), James Only This Time They’re W. Long (LSU Press), and additional special guests. Designed to Confront the Friday, July 16, 1 p.m. Uncomfortable Questions. That’s EST: Teaching The Sun Also Rises, moderated by Juliet Why We’re Calling It: Conway We’ll kick off the literary discussions with a panel on Two classic posters from Hemingway’s teaching The Sun Also Rises, moderated dangerous summer suggest the spirit of ours: by recent University of Edinburgh A Dangerous the courage, skill, and grace necessary to Ph.D. alumna Juliet Conway, who has a confront the bull. (Courtesy: eBay) great piece on the novel in the current Summer Hemingway Review. Dig deep into n one of the most powerful passages has voted to offer a series of webinars four Hemingway’s Lost Generation classic. in his account of the 1959 bullfighting Fridays in a row in July and August. While Whether you’re preparing to teach it rivalry between matadors Antonio last summer’s Houseguest Hemingway or just want to revisit it with fellow IOrdóñez and Luis Miguel Dominguín, programming was a resounding success, aficionados, this session will review the Ernest Hemingway describes returning to organizers don’t want simply to repeat last publication history, reception, and major Pamplona and rediscovering the bravery year’s model. -

Protectionprevention

WFM-IGP ANNUAL REPORT 2014/2015 protectionprevention Peace. JOIN US to mobilize to effectively support the Rohingya, despite warnings ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER from human rights groups and activists. The unaddressed, rampant discrimination facing the Rohingya, SAIFUL and other ethnic minorities, casts a dark shadow on the fragile HUQ OMI democratic transition in Myanmar. Saiful’s photography illumi- nates the individual, amid forces working to deny them of their “Using my lens rights. At the date of publication, Saiful is in the midst of shooting to help create a a full length documentary on the Rohingya population. better world” For WFM-IGP, ‘No 136’ provides striking and vivid narratives of the individuals our work is geared towards supporting. We hope learning of these individuals and their stories affirms for you, as it does for us, the need to be relentless in efforts not just to pro- tect, but to prevent these harrowing narratives, and holistically work towards peace. This Annual Report features four stunning – yet haunting – im- ON THE COVER ages by photo activist, Saiful Huq Omi. Saiful hails from Bangla- Taken in 2009, on Bangladesh’s border, the image captures desh, and uses his camera as a medium for advocacy, through Saiful’s Rohingya guide as he points towards Myanmar, just on which to tell important stories of individuals. His photos have ap- the other side of the river. He told Saiful: “My home is not far peared in The New York Times, The Economist, and The Guardian, from here, you just cross the river Naaf and there is my home by amongst others, and his work has been on exhibit in galleries on the riverside. -

Stewardship in West African Vodun: a Case Study of Ouidah, Benin

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2010 STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN HAYDEN THOMAS JANSSEN The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation JANSSEN, HAYDEN THOMAS, "STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN" (2010). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 915. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/915 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN By Hayden Thomas Janssen B.A., French, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2003 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Geography The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2010 Approved by: Perry Brown, Associate Provost for Graduate Education Graduate School Jeffrey Gritzner, Chairman Department of Geography Sarah Halvorson Department of Geography William Borrie College of Forestry and Conservation Tobin Shearer Department of History Janssen, Hayden T., M.A., May 2010 Geography Stewardship in West African Vodun: A Case Study of Ouidah, Benin Chairman: Jeffrey A. Gritzner Indigenous, animistic religions inherently convey a close relationship and stewardship for the environment. This stewardship is very apparent in the region of southern Benin, Africa. -

Carmel Pine Cone, January 20, 2012

A Special Section inside this week’s Healthy Lifestyles Carmel Pine Cone ON THE MONTEREY PENINSULA JANUARY 20, 2012 Volume 98 No. 3 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com January 20-26, 2012 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 P.G. mayor drops bid April ballot set with six candidates for Assembly, will By MARY SCHLEY A LATECOMER kept the city’s staff working into the evening challenge Potter instead Wednesday verifying that all six candidates for the April 10 Carmel municipal election had enough valid signatures to get their names on By KELLY NIX the ballot, assistant city clerk Molly Laughlin said Thursday. The latest candidate to enter the race, Bob Profeta, met with THE MAYOR of Pacific Grove, Carmelita Garcia, has Laughlin Wednesday morning to pick up his nomination papers for dropped her bid for State Assembly and turned her attention the city council race and managed to get the required 20 to 30 sig- toward a political office closer to home. natures by the 5 p.m. deadline the same day. Garcia announced this week she intends to run against Profeta, who co-owns Alain Pinel Realtors in Carmel with his incumbent Dave Potter for supervisor of the 5th District, an wife, Judie, said he extensively discussed a potential run for council area that includes Carmel, Carmel Valley, Pebble Beach and with her before deciding to commit to the effort. With decades of Pacific Grove. experience helping to start nuclear power plants all over the world, When Garcia disclosed in November 2011 she was run- and having lived in Carmel for more than 20 years, Profeta said he ning for Assembly, she said, “It’s time for a new leadership has the management skills and time to give back to the city he appre- and an honest discussion about our state’s priorities.” She ciates so much. -

2016 Fall Feature Auction Weekend

62 — Antiques and The Arts Weekly — November 11, 2016 Page 3 of 10 Lot 525 - 19th c Sidewalk Trade Advertising Cigar Store indian, attr. to Thomas Brooks, in carved and painted wood with cast concrete elements to the base, 57” x 20” x 19” est. $25000 - $35000 Lot 530 - Early 20th c. Lot 722 - Old Master Icon, Continental Carved and Painted 2016 Fall Feature Auction Madonna and Child, oil on panel, Wood Carousel Horse, 15 3/4” x 11 3/4” est. $2000 - $3000 roughly 48” x 48” x 12” est. $2000 - $3000 Weekend Day 2 & Day 3 Fine Art & Antiques Sat. & Sun., Nov. 19 & 20, 11 am Preview: Mon – Thurs, Nov. 14 - 17, 9 am–5 pm Held at our gallery in Thomaston, Maine 207-354-8141 | [email protected] View our complete catalog at www.thomastonauction.com DAY 2 & 3 FINE ART & ANTIQUES HIGHLIGHTS • William Trost Richards oil on canvas seascape painting Lot 631 - WILLIAM HENRY KNIGHT (UK, 1823- Lot 506 - 19th c. “Black Hawk” Running Horse Weathervane 1863) - “Blowing Bubbles”, oil on panel, signed in patinated copper with cast zinc ears, attr. to Harris and • Outstanding 19th c. carved cigar store Indian figure and titled, 19 1/2” x 15 1/2” est. $7000 - $9000 Company, Boston, Mass. Ca. 1875-1890. 16 1/2” x 25” est. $1000 - $2000 • Pair of high carat gold Etruscan Revival bracelets • 109 lots of Asian antiques • 1920s Louis Vuitton steamer trunk • Oill on canvas ship painting by Thomas Buttersworth • Important pair of Chinese cloisonné double gourd vases • 65 lots of Fine Jewelry and Pocket Watches • 31 Estate Silver lots, incl. -

Hemingway and the Influence of Religion and Culture

HEMINGWAY AND THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGION AND CULTURE ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University Dominguez Hills ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Humanities ____________ by Jeremiah Ewing Spring 2019 Copyright by Jeremiah Ewing 2019 All Rights Reserved This work is dedicated to my father, Larry Eugene Ewing, who finished his Master’s in Liberal Arts in 2004 from California State University, Sacramento, and encouraged me to pursue my own. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks to Dr. Lyle Smith who helped and guided me through the process. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE COPYRIGHT PAGE .......................................................................................................... ii DEDICATION ................................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iv TABLE OF CONTENTS .....................................................................................................v ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................1 New Historicism ......................................................................................................1 The Cultural Context and Overview -

Overseas Column from 1929 Commonwealth Organisation That Offers Clubhouse Facilities to Members, Organises Commonwealth an Equal Footing

OVER SEAS Journal of the Royal Over-Seas League Issue 2, June –August 2010 Namibia special A woman’s worth Make it a date ROSL on film Looking to the past, present Kamalesh Sharma strives Book ahead and fix dates in How the commemorative and future as the ROSL- for equality; and we profile your diary with this issue’s DVD was made, from the Namibia project celebrates the Commonwealth’s most Events section, featuring planning stages, through its 15th anniversary influential women the centenary events filming, to post-production OVER SEAS 16 From the Chairman; Editor’s letter . 4 Centenary OVER SEAS ‘From a woman’s ISSUE 2 June-August 2010 standpoint’ . 5 The Royal Over-Seas League is a self-funded The popular Overseas column from 1929 Commonwealth organisation that offers clubhouse facilities to members, organises Commonwealth An equal footing . 5 art and music competitions and develops joint Adele Smith’s ‘History’ on ROSL’s inclusivity welfare projects with specific countries. Overseas editorial team Editor Miranda Moore The making of the Deputy Editor/Design Middleton Mann Assistant Editor Samantha Whitaker Centenary DVD . 6 Thailand’s top talent . 24 Tel 020 7408 0214 x205 Polly Hynd looks at the challenges Meet the new Young Musician and Young Artist Email [email protected] Display Advertisements Melissa Skinner Tel 020 8950 3323 ROSL Annual Report 2009 . 25 Email [email protected] World Royal Over-Seas League ROSL world . 26 Incorporated by Royal Charter 15 years on… . 8 The Chairman’s tour, and other branch activities Patron Her Majesty The Queen Vice-Patron Her Royal Highness An overview of the ROSL-Namibia project Princess Alexandra KG GCVO Turn of the centenary . -

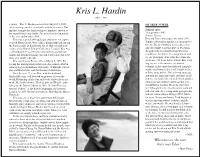

Kris L. Hardin Obituary

Kris L. Hardin 1953 ~ 2012 CARMEL – Kris L. Hardin passed away August 21, 2012 MY TRUE NORTH after a courageous five-year battle with brain cancer. Dur - ing that struggle she displayed grace, kindness and wit to Journal entry her many friends and family. She never lost her humanity 29 September 2003 or the love and wonder of life. Sounio, Greece Kris was a gifted anthropologist and writer who spent Kris and I have hiked up to the ruins of the years in Sierra Leone, West Africa, doing fieldwork among Temple of Poseidon and the sea opens up be - the Kono people of Kainkordu. All of that research now fore us. The breathtaking vista makes clear resides in the British Library Collection, London. Kris was why the temple was built here. If Poseidon, a talented painter as well who only recently shared with the god of the sea, had lived anywhere he family and friends her many oils and watercolors that were would have lived here. It is magnificent and done over nearly a decade. we are gloriously alone with these ruins cre - Kris was born in Fresno, CA on March 7, 1953. Fol - ated some 440 years before Christ. Kris is sit - lowing her undergraduate education, she earned a PhD in ting on one of the massive overturned anthropology from Indiana University, a Fulbright scholar - columns as she opens her rucksack and pulls ship and Rockefeller and Smithsonian fellowships. out the small watercolor box I bought for her Over the next 25 years Kris, with her husband, in Paris years before. -

Earth Matters: Studies for Our Global Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 427 973 SE 062 276 AUTHOR Wasserman, Pamela, Ed. TITLE Earth Matters: Studies for Our Global Future. 2nd Edition. INSTITUTION Zero Population Growth, Inc., Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-945219-15-6 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 224p.; For previous edition, see ED 354 161. AVAILABLE FROM Zero Population Growth, 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 320, Washington, DC 20036; Tel: 202-332-2200. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Air Pollution; *Critical Thinking; *Environmental Education; *Global Education; High Schools; Learning Activities; *Population Education; Secondary Education; Standards; Waste Disposal; Water Pollution; *Wildlife ABSTRACT This teacher's guide helps students explore the connection between human population growth and the well-being of the planet. Twelve readings and 34 activities introduce high school students to global society and environmental issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, gender equality, economics, poverty, energy, wildlife endangerment, waste disposal, food and hunger, water resources, air pollution, deforestation, and population dynamics. Teaching strategies include role playing simulations, laboratory experiments, problem-solving challenges, and mathematical exercises, cooperative learning projects, research, and discussion. These activities were designed to develop a number of student skills including critical thinking, research, public speaking, writing, data collection and analysis, cooperation, decision making, creative problem solving, reading comprehension, conflict resolution and values clarification. Each chapter and activity can be used alone to illustrate points or be inserted into existing curriculum. Activity subject areas are listed along with a quick list reference of the summary of activities. A reference guide of activities linked to National Standards is also included. -

Nonfiction Book,On Desperate Ground: the Ways: a Double Journey Along My Grandmoth- Marines at the Reservoir, the Korean War’S Er’S Far-Flung Path

THE 1511 South 1500 East Salt Lake City, UT 84105 InkslingerHoliday Issue 2 018 801-484-9100 Finding the “Perfect” Gift Because books fill every role imaginable from escape to education to On a very different note, for those trying to make sense of an epiphany, if carefully selected they make exquisitely thoughtful gifts. increasingly chaotic world, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Leadership in Personal gifts, since matching the right book to the person receiv- Turbulent Times, Michael Beschloss’ Presidents of War and Ameri- ing it can literally change his or her life. Or fill it with much-needed can Dialogue: The Founding Fathers and Us by Joseph J. Ellis, or laughter. Or the kind of knowledge that might be acutely necessary at on a fictional note, Kate Atkinson’s ironic take on our tribal selves, a given point… Transcription, are all books which remind us of the complexity of If, for instance, you’re sorting through the issues that have haunted this country since its inception, giving us the wonderful array of books new this year comfort of context. looking for a gift for a young woman—or To fill the world of a loved one with much-needed laughter, The for that matter a woman of any age—who Shakespeare Requirement (“To be or not to be” never felt this funny) is finding her way in the world, looking by Julie Schumacher, the big-hearted Virgil Wander by Leif Enger, backward and forward to try to map a and Hits & Misses: Stories by Simon Rich are all sure to elicit guffaws course or find a place of comfort or mean- or snorts of one kind or another, while books such as RX by Rachel ing, Katharine Coles’ hybrid biography/ Lindsay and There, There by Tommy Orange strike a darkly hilarious memoir Look Both Ways: A Double Journey note, making us laugh even while making starkly evident the seem- Along My Grandmother’s Far-Flung Path, a complex pas-de-deux ingly unbridgeable chasms that separate us. -

Title Author Publisher Location Date Cover ISBN Details/Condition

Details/Condition/ Title Author Publisher Location Date Cover ISBN Quantity Matters for Men: How to Stay healthy and keep life on track (Revised Edition) John Ashfield Peacock Publications Adelaide, Australia 6/1/2009 Paperback 1 921601 01 9 44 copies ISBN-13 978-1-59403- Indoctrination U: The Left's War Against Academic Freedom David Horowitz Encounter Books 3/23/2009 Paperback 237-0 Dracula (Wordsworth Classics) Bram Stoker Wordsworth Editions Ltd 4/1/1993 Paperback 1-85326-086-X Whole Stole Feminism? How women have betrayed women Christina Hoff Sommers Touchstone, New York 1995 Paperback 0-684-80156-6 Jane Eyre Charlotte Bronte Penguin Classics (1847) 1985 Soft 9780140430110 American Nerd: The Story of my People Benjamin Nugent Scribner 2008 Soft 9780743288026 Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking Malcolm Gladwell Black Bay Books 2005 Soft 9780316010665 The Victim's Revolution Bruce Bawer Broadside 2012 Hard 9780061807374 A Tale of Two Cities Charles Dickens Wordsworth Classics (1859) 1993 Soft 9781853260391 Lord Jim Joseph Conrad Wordsworth Classics (1900) 1993 Soft 9781853260377 Aspects of the Masculine/Aspects of the Feminine C.G. Jung MJF Books 1989/1982 Hard 9781567311372 The Closing of the American Mind Allan Bloom Simon and Schuster 1987 Hard 6714479903 Leviathan Thomas Hobbes Oxford World Classics (1651) 1996 Soft 9780192834980 Spreading Misandry: The Teaching of Contempt for Men in Paul Nathanson and Katherin Popular Culture K. Young McGil/Queens UP 2001 Soft 9780773530997 cover torn off The Republic Plato Penguin Classics 1987 Soft 9780140440485 Ivanhoe Sir Walter Scott Wordsworth Classics 1995 Soft 9781853262029 Warren Farrell with Steven Does Feminism Discriminate Against Men? Svoboda vs. -

Friends Newsletter Winter 2011 V3:Layout 1

Win tickets to see on stage Senders of the first three correct crossword sweetly innocent Mrs Wilberforce who, solutions opened will each win a pre- alone in her house, is pitted against a gang Christmas treat – a pair of top-price tickets to of criminal misfits who will stop at nothing. The Ladykillers at London’s Gielgud Theatre. The tickets will be valid for performances The famous Ealing comedy comes to life on between Monday 19 and Thursday 22 stage in a hilarious and thrilling new adaption December, subject to availability. There is by Graham Linehan (writer of Father Ted), no cash alternative. Include your name, directed by Sean Foley (The Play What I address, membership number and a Wrote). The stellar cast includes Peter Capaldi telephone number or e-mail address so that (from The Thick of It), James Fleet (The Vicar the theatre’s representative can contact you of Dibley) and Ben Miller (The Armstrong if you win. Closing date: 7 December. and Miller Show). Marcia Warren plays the Across 6 (with 14) Crowning glories lit up in Library show (5,11) 7 This goes around twisted body parts as a measure of substance (9) 10 Saint penetrated by sharp object in disorder, and it hurts (7) 11 Auden's caused joy for girl and boy, amongst others (7) 12 Foolish Amin has nothing before a twitch (7) 13 He's immortalised in Oxford showpiece (7) 14 (see 6) (11) 19 Descartes married and was quite restored (7) 21 World body adds garment only to remove it (7) 23 US video cunningly mixed (7) 25 Lenin gets awkward (7) 26 Fat welder turned to old pots (9)