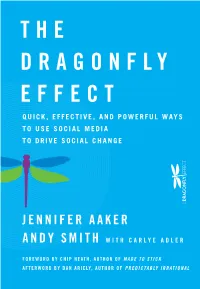

The Dragonfly Effect by Jennifer Aaker & Andy Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Codexis Adds Dr. Jennifer L. Aaker to Its Board of Directors

August 6, 2020 Codexis Adds Dr. Jennifer L. Aaker to its Board of Directors REDWOOD CITY, Calif., Aug. 06, 2020 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Codexis, Inc. (Nasdaq: CDXS), a leading protein engineering company and developer of high-performance enzymes, announced the appointment of Jennifer L. Aaker, Ph.D. to its board of directors, expanding membership to nine directors. Dr. Aaker is the General Atlantic Professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, and a leading behavioral scientist, scholar, and best- selling author. Her unique expertise helps companies and leaders build cultures that harness purpose, story and technologies, and facilitates improved implementation of novel strategies that enhance growth and societal impact. “Recognizing the ambitious growth strategy for Codexis and the importance of reshaping and aligning our organization and our corporate identity for that purpose, this as an ideal time to welcome Dr. Jennifer Aaker to the board. She brings a new, fresh and valuable perspective that will help Codexis take advantage of the many opportunities for our platform technology to deliver products for improving human health and well-being,” said Bernard Kelley, Chairman of Codexis. “Her proven methods for developing powerful and memorable narratives for growth will drive us to a new level of engagement and impact with our stakeholders.” “I am delighted to join the board at a pivotal moment where Codexis is harnessing its artificial intelligence powered platform to fulfill its potential to make a meaningful difference in the world,” said Dr. Aaker. “I look forward to combining the power of technology with human- centered design to help to create a strong future for Codexis.” Dr. -

Author Talks: the Collection

Author Talks: The collection A series of interviews with authors of books on business and beyond. Summer/Winter 2021 Cover image: Edu Fuentes Copyright © 2021 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved. This publication is not intended to be used as the basis for trading in the shares of any company or for undertaking any other complex or significant financial transaction without consulting appropriate professional advisers. No part of this publication may be copied or redistributed in any form without the prior written consent of McKinsey & Company. To request permission to republish an article, email [email protected]. Author Talks: The collection A series of interviews with authors of books on business and beyond. Summer/Winter 2021 Introduction Welcome to Author Talks, McKinsey Global Publishing’s series of interviews with authors of books on business and beyond. This collection highlights 27 of our most insightful conversations on topics that have resonated with our audience over this challenging pandemic period, including CEO-level issues, work–life balance, organizational culture shifts, personal development, and more. We hope you find them as inspirational and enlightening as we have. You can explore more Author Talks interviews as they become available at McKinsey.com/author-talks. And check out the latest on McKinsey.com/books for this month’s best-selling business books, prepared exclusively for McKinsey Publishing by NPD Group, plus a collection of books by McKinsey authors on the management issues that matter, from leadership and talent to digital transformation and corporate finance. McKinsey Global Publishing 2 Contents Leadership and Innovative thinking History organization 60 Gillian Tett on looking at the 97 Michelle Duster on the legacy of world like an anthropologist Ida B. -

THE WICT SENIOR EXECUTIVE SUMMIT (SES) March 1 - 5, 2015 the Agile Leader: Building and Managing Innovative Teams

THE WICT SENIOR EXECUTIVE SUMMIT (SES) March 1 - 5, 2015 The Agile Leader: Building and Managing Innovative Teams SUN, MAR 1 MON, MAR 2 TUE, MAR 3 WED, MAR 4 THU, MAR 5 6:00 - 6:45 am Optional Yoga Optional Yoga Optional Yoga Optional Yoga 7:00 - 7:50 am Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Leading Innovation I: Creating Qualcomm Realizing Synergy: Managing Critical Post-Partum: Seizing Opportunity I Capture Your Learnings 8:00 - 9:20 am Barnett Conflict in Teams I Shiv Gruenfeld Neale 9:20 - 9:40 am Break Break Break Break Leading Innovation II Realizing Synergy: Managing Critical Post-Partum: Seizing Opportunity II The Big Picture 9:40 - 11:00 am Barnett Conflict in Teams II Shiv Gruenfeld Neale 11:00 - 11:20 am Break (Group Photo) Break Break Break Check In Available at the Schwab Leveraging Compositional Advantage I Pre-Mortem: Forecasting Disruption Driving Innovation & Problem Solving The Big Picture 11:20 am - 12:40 pm Residential Center after 12:00pm Neale Shiv with Team-Based Design Thinking I Gruenfeld 12:00 - 4:00 pm Klein Lunch (Computer Support will be Lunch Driving Innovation & Problem Solving Box Lunches Available Computer Support available in R115 available during lunch in West Vidalakis with Team-Based Design Thinking II (and 12:40 - 2:00 pm 2:00 - 4:00 pm dining room) Lunch) Klein Meet in the Main Lobby of the Schwab Residential Center to walk to P106 for Leveraging Compositional Advantage II Team Engagement Through Vision: The Company Visit: Apple Computer Please plan to check out of the Schwab Neale 2:00 - 5:00 pm 2:00 - 3:20 pm our first session. -

The Dragonfly Effect

THE DRAGONFLY EFFECT QUICK, EFFECTIVE, AND POWERFUL WAYS TO USE SOCIAL MEDIA TO DRIVE SOCIAL CHANGE JENNIFER AAKER ANDY SMITH WITH CARLYE ADLER FOREWORD BY CHIP HEATH, AUTHOR OF MADE TO STICK AFTERWORD BY DAN ARIELY, AUTHOR OF PREDICTABLY IRRATIONAL The Dragonfly effecT Quick, effecTive, anD Powerful ways To use social MeDia To Drive social change Jennifer aaker anDy sMiTh With Carlye adler Copyrighted material © 2010. All rights reserved. Published by Jossey-Bass, a Wiley imprint. Aaker.ffirs.indd 3 7/21/10 11:18 AM Copyright © 2010 by Jennifer Aaker and Andy Smith. All rights reserved. Published by Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741—www.josseybass.com No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read. -

Association for Consumer Research

ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Labovitz School of Business & Economics, University of Minnesota Duluth, 11 E. Superior Street, Suite 210, Duluth, MN 55802 If It’S Similar, It’S More Likely… But Can It Be Worth It? Perceived Similarity, Probability and Outcome Value Hui-Yun Chen, Virginia Tech, USA Elise Chandon Ince, Virginia Tech, USA Assessment of precise probabilities is difficult, and research has pointed to various cues people use to form probability judgments. In this research we investigate the effect of enhancing perceived proximity on probability judgments. Furthermore, we propose that inflated probability judgments could in turn abate perceived impact level of the event. [to cite]: Hui-Yun Chen and Elise Chandon Ince (2011) ,"If It’S Similar, It’S More Likely… But Can It Be Worth It? Perceived Similarity, Probability and Outcome Value", in NA - Advances in Consumer Research Volume 38, eds. Darren W. Dahl, Gita V. Johar, and Stijn M.J. van Osselaer, Duluth, MN : Association for Consumer Research. [url]: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/16111/volumes/v38/NA-38 [copyright notice]: This work is copyrighted by The Association for Consumer Research. For permission to copy or use this work in whole or in part, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at http://www.copyright.com/. 568 / Top 10 or #10?: How Positional Inferences Influence the Effectiveness of Category Membership Claims to social judgments, which may be somewhat more motivational Liberman, Nira, Michael D. Sagristano, and Yaacov Trope and less cognitive in nature. (2002), “The Effect of Temporal Distance on Level of Mental Construal,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38 REFERENCES (6), 523-34. -

Social Media and the Future of U.S. Presidential Campaigning Annie S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship@Claremont Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2016 Social Media and the Future of U.S. Presidential Campaigning Annie S. Hwang Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Hwang, Annie S., "Social Media and the Future of U.S. Presidential Campaigning" (2016). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 1231. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1231 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT MCKENNA COLLEGE SOCIAL MEDIA AND THE FUTURE OF U.S. PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGNING SUBMITED TO PROFESSOR JOHN J. PITNEY, JR. AND DEAN PETER UVIN BY ANNIE HWANG FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL 2015 NOVEMBER 30, 2015 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Pitney for his incredible support and patience. Thank you for putting in the time and efforts in directing me to endless resources and editing my chaotic chapters – Strunk & White typos and all. I am so grateful to have worked with such a brilliant and dedicated thesis advisor. Thank you. I would also like to thank my mom and dad for being extremely supportive – and adding money to my Starbucks app. And lastly, thank you to my friends who have selflessly offered help and provided thoughtful encouragements throughout this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2: The 2008 Election……………………………………………………………..7 Chapter 3: The 2012 Election……………………………………………………………20 Chapter 4: The 2016 Election……………………………………………………………31 Chapter 5: Conclusion……………………………………………………………………43 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..44 INTRODUCTION “Communication is the essence of a political campaign,” wrote White House media advisor Bob Mead in 1975.1 Effective communication allows a presidential candidate to relay his or her message and rally support. -

Behavioral Economics and Social Policy Designing Innovative Solutions for Programs Supported by the Administration for Children and Families

Technical Supplement Commonly Applied Behavioral Interventions BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL POLICY Designing Innovative Solutions for Programs Supported by the Administration for Children and Families OPRE Report No. 2014 -16b April 2014 BIAS BEHAVIORAl iNTERVENTIONs to aDVANCe seLf- SUFFICIENCy THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL POLICY Designing Innovative Solutions for Programs Supported by the Administration for Children and Families technical supplement: commonly applied behavioral interventions April 2014 OPRE Report No. 2014-16b April 2014 Authors: Lashawn Richburg-Hayes, Caitlin Anzelone, Nadine Dechausay (MDRC), Saugato Datta, Alexandra Fiorillo, Louis Potok, Matthew Darling, John Balz (ideas42) Submitted to: Emily Schmitt, Project Officer Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation Administration for Children and Families U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Project Director: Lashawn Richburg-Hayes MDRC 16 East 34th Street New York, NY 10016 Contract Number: HHSP23320095644WC This report is in the public domain. Permission to reproduce is not necessary. Suggested citation: Richburg-Hayes, Lashawn, Caitlin Anzelone, Nadine Dechausay, Saugato Datta, Alexandra Fiorillo, Louis Potok, Matthew Darling, John Balz (2014). Behavioral Economics and Social Policy: Designing Innovative Solutions for Programs Supported by the Administration for Children and Families, Technical Supplement: Commonly Applied Behavioral Interventions. OPRE Report No. 2014-16b. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.