CORPORATE MANSLAUGHTER: New Horizon Or False Dawn?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

For Our Time EUROPE 8I Moresignsthat Britain Is Makingthe Grade in Eurcpe

August/September 1981 Picasso and Turner - European painters for our time EUROPE 8I Moresignsthat Britain is makingthe grade in Eurcpe Our breakdown of the performance of British industry i.n Europe Published by the Commission of the (page I5),based on the latest figures, confirms that the United. European Communities, 20 Kensington Kingdom's trade with the rest of tlr.e Community continues to Palace Gardens, London tI78 4QQ. Tel: 0l-727 8090 increase, despite a falling-off in such traditional industries as iron and steel andmotor car manufacture.Areport onthe cross-Channel Editor-in-Chief: George Scott ferries, on the Business Page, tells a similar story. Editor: JohnGreenwood Associate Editor: Denis Thomas Desigl : Lawrence Edwards Our second rep ort ( opposite ) on how European fund.s are being mad.e available to help in the recovery of IAIales, covers both southern and Printed by Lawrence-Allen Ltd, lU7eston-super-Mare, Avon northern parts of the Principality. In both regions ttre prospects 1ook Europe 8l does not necessarily reflect, goodfor tourism - now accepted throughout Europe as a key area for in all economic growbh. particulars, the opinions of the Community institutions. Unsigned material may be quoted or reprinted without payment, We also report on two Britlsh families who are making new lives for subiect to suitable acknowledgement. themselves in France (page g), and on the situation in Tanzania, where European aid, under the terms of Lome Belfust Offce : W'ndsor House, the agreements, is 9/15 Bedford Street, Belfast BT2 7EG being put to urgent use (page 7). Tel. (0232) 40708 C ardiff Offi ce : 4 Cathedral Road, CardiffCFl 9SG Anyone who is con-firsed by stories of how EEC regulations are Tel. -

Doctor Portable Reference March 2015

DOCTOR REFERENCE LIST – March 2015 COMPANY INDUSTRY Aaby, Norway Shipping Abou Merhi, Lebanon Shipping ADNATCO, UAE Shipping ADtranz, UK Servicing Aker Yard, Germany Shipbuilding AP Moller, Denmark Shipping Allocean, UK Shipping Amer, Cyprus ` Shipping American Eagle Tankers, Singapore Shipping American Eagle Tankers, Malaysia Shipping American Eagle Tankers, USA Shipping Amoco, USA Gas Distribution AND, UK Shipping Equipment Andrew Weir Shipping, UK Shipping Anglo-Belgian Corporation, Belgium Engine Manufacturer Anglo Eastern, UK Shipping Anglo Eastern, Hong Kong Shipping Anglo Eastern, Singapore Shipping APL, Oakland, USA Shipping Atlantic Spa di Navigazione, Italy Shipping Aygas, Turkey Shipping B&H Equimar, Singapore Shipping Ballast Ham Dredging, Netherlands Shipping Barber Ship Management, Norway Shipping BELCO, Bermuda Power Berge Bulk, Singapore Shipping Bergesen, Norway Shipping Bernard Schulthe, Cyprus, UK, Hong Kong , Singapore Shipping Bluewater Marine, UK North Sea Oil Bluewater Shipping, UK Shipping BNFL, Sellafield, UK Power Bona Shipping, Norway Shipping Boskalis, Holland Shipping BP Oil, UK Shipping BP Sullom Voe, UK Power BP Shipping Shipping British Antarctic Survey, UK Shipping British Energy, UK Power British Polar Engines , UK Engine Manufacturer BS Shipping, Cyprus Shipping BS Shipping, IOM Shipping BS Shipping, Singapore Shipping BS Shipping, UK Shipping BUE – Kazakhstan Shipping BW Shipping, Singapore Shipping BW Gas, Norway Shipping Caledonian MacBrayne, UK Shipping Carisbrooke Shipping, UK Shipping Caterpillar, -

P&O Ferries Is More Than 170 Years Old and Offers a Choice of Four Routes Sailing from the UK to the Continent. Its Service

34069_CSB_072-073_P&O 14/6/07 11:26 am Page 72 P&O Ferries is more than 170 years old and offers a choice of four routes sailing from the UK to the Continent. Its service offering is based on the company ethos of an affordable and hassle free travel experience that is simple, flexible and focused. With no hidden or excess baggage charges, the fleet of cruise style ships offers a viable alternative to European airline and train travel. Market The cross channel market has become increasingly competitive in recent years with customers focused on both price as well as service levels – a trend which looks set to continue. Low cost airlines which offer cut priced fares on flights to the Continent have grown in popularity. In addition, the chunnel and Eurostar services offer another alternative. This is an increasingly important factor with the launch of Eurostar services from Kings Cross St Pancras in late 2007. As a result of this level of choice, customers have become less loyal, shopping around for the best deal. Achievements The Peninsular Steam Navigation Company started regular paddle steamer mail services between England, Spain and Portugal in 1837. After this route expansion saw the company become The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company – P&O. Now, more than 170 years after its services began, P&O Ferries is still sailing strong and receiving recognition for its high standards of service. Named Cruise/Ferry Travel Retailer of the Year at the 2007 Raven Fox Global Travel Retail Awards, the company was voted Best Ferry Operator as well as Favourite Ferry customer service and staff training, winning of services and facilities as well as a Company at the British Travel Awards 2006. -

Port Privatisation: Ownership Involvement by External Companies

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MARITIME SCIENCE MASTER DISSERTATION Academic year 2017 – 2018 Port privatisation: Ownership involvement by external companies Alan Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements Supervisor: Prof. dr. Theo Notteboom for the degree of: Master of Science in Maritime Science Assessor: Prof. Daan Schalck PERMISSION I declare that the content of this Master dissertation may be consulted or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced. Alan Johnson PREFACE This Master dissertation marks the conclusion of my advanced studies in the Master of Science in Maritime Science. I would like to explicitly thank certain people who have contributed to the realisation of this thesis. In the first place, I wish to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. dr. Theo Notteboom and co-promotor Prof. Daan Schalck for their confidence and valuable feedback. Their willingness and assistance have resulted in the accomplishment of this dissertation. Furthermore, my appreciation goes to the interviewees for their cooperation and insights as well as to the respondents for completing the survey regarding my qualitative research. Many thanks go to my friends who are always available for advice. Their relentless and unconditional enthusiasm mean a lot to me. Last but not least, I am deeply grateful to my parents for the opportunity they have offered me to follow and finalise this additional master programme. Their exceptional support and motivation are extremely valuable for me. Alan Johnson Ghent, 24 January 2018 I II -

Conditions of Itx Approval

P&O FERRIES 5. BOOKINGS CONDITIONS FOR INCLUSIVE TOUR RATES 5.1 – No bookings are to be made in connection with a newly negotiated fare until the Company has confirmed any special requirements necessary to make such bookings. By making a booking, the Operator is deemed to accept these terms and conditions. As an overriding condition the parties acknowledge that no booking 5.2 – Subject to the provisions of paragraph 5.3, fares are only guaranteed once the made by the Operator shall give rise to any liability on the Company’s part until booking has been confirmed to the Operator by way of a booking reference. the Company has advertised generally its schedules covering the period during which the Operator wishes such booking to be discharged. All such bookings 5.3 – In the event of an increase in general operating costs, the Company reserves the shall be conditional upon formal written acceptance by the Company after right to make a surcharge at the time of booking. In addition, a surcharge may be publication of the said schedules. made as a result of any increase in costs between the date of booking and the date of travel. This may be applied to all passenger and/or vehicle bookings and will be The special ITX rates (the “Contract Rates”) are made available by either (a) P&O collected prior to the outward journey. A reduction or a removal of a surcharge will Short Sea Ferries, for sailings on a Short Sea route; (b) P&O North Sea Ferries, for affect only new bookings made from the date of change. -

DRAGON (1967) Later IONIC FERRY

Ship Fact Shee t DRAGON (1967) later IONIC FERRY Base data at 15 June 1967. Last amended December 2009 * indicates entries changed during P&O Group service. Type Roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry P&O Group service 1967-1985 and 1987-1992 P&O Group status* Owned by subsidiary company Former name(s) Registered owners* and General Steam Navigation Company Ltd managers* Operators* Normandy Ferries (P&O interest 50%) Builders Ateliers et Chantiers de Bretagne Yard Nantes Country France Yard number 16/108 Completed by Dubigeon Normandie SA Yard Nantes-Chantenay Country France Yard number 824 Registry Southampton, UK Official number 333697 Call sign GXWU IMO/LR number 6710906 Classification society Lloyd’s Register Gross tonnage* 6,141 grt Net tonnage* 2,732 nrt Deadweight* 2,100 tons Length 134.57m (441.7ft) loa; 126.50m (415.0ft) b/p Breadth 21.86m (71.8ft) Depth 11.73m (38.5ft) Draught 4.820m (15.8ft) Engines 2 SEMT-Pielstick diesel engines Engine builders* Chantiers de l’Atlantique Works St Nazaire Country France Power* 9,467 bhp Propulsion Twin controllable-pitch screws Speed 19 knots 0478 1967/0615 DRAGON (1967) later IONIC FERRY Passenger capacity* 850: 276 in 2 or 4 berth cabins, plus 156 reclining seats and 244 couchettes Cargo capacity 65 teu plus 250 cars or 510 linear metres of freight Crew Employment Southampton/Le Havre service. Later Cairnryan/Larne Career 16.09.1966: Keel laid. 27.01.1967: Launched by Mrs D J L Mortelman, wife of the Chairman of the General Steam Navigation Company. 15.06.1967: Delivered as Dragon for General Steam Navigation Company Ltd. -

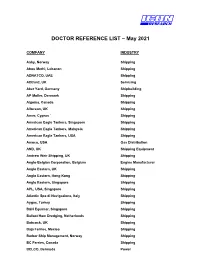

DOCTOR REFERENCE LIST – May 2021

DOCTOR REFERENCE LIST – May 2021 COMPANY INDUSTRY Aaby, Norway Shipping Abou Merhi, Lebanon Shipping ADNATCO, UAE Shipping ADtranz, UK Servicing Aker Yard, Germany Shipbuilding AP Moller, Denmark Shipping Algoma, Canada Shipping Allocean, UK Shipping Amer, Cyprus ` Shipping American Eagle Tankers, Singapore Shipping American Eagle Tankers, Malaysia Shipping American Eagle Tankers, USA Shipping Amoco, USA Gas Distribution AND, UK Shipping Equipment Andrew Weir Shipping, UK Shipping Anglo-Belgian Corporation, Belgium Engine Manufacturer Anglo Eastern, UK Shipping Anglo Eastern, Hong Kong Shipping Anglo Eastern, Singapore Shipping APL, USA, Singapore Shipping Atlantic Spa di Navigazione, Italy Shipping Aygas, Turkey Shipping B&H Equimar, Singapore Shipping Ballast Ham Dredging, Netherlands Shipping Babcock, UK Shipping Baja Ferries, Mexico Shipping Barber Ship Management, Norway Shipping BC Ferries, Canada Shipping BELCO, Bermuda Power Berge Bulk, Singapore Shipping Bergesen, Norway Shipping Bernard Schulte, Cyprus, UK, Hong Kong , Singapore Shipping Bluewater Marine, UK North Sea Oil Bluewater Shipping, UK Shipping BNFL, Sellafield, UK Power Bona Shipping, Norway Shipping Boskalis, Holland Shipping BP Oil, UK Shipping BP Sullom Voe, UK Power BP Shipping Shipping British Antarctic Survey, UK Shipping British Energy, UK Power British Polar Engines , UK Engine Manufacturer BS Shipping, Cyprus Shipping BS Shipping, IOM Shipping BS Shipping, Singapore Shipping BS Shipping, UK Shipping BUE – Kazakhstan Shipping BW Shipping, Singapore Shipping -

P&O Ferrymasters Haulier Handbook

P&O Ferrymasters Haulier Handbook Version 2.0 Table of Amendments Date of Amendment and Version Section Reference Amendment July 2015 (Version 1.0) 8.1; 8.2; 8.3; 8.4; 8.5 Use of Temperature Probes October 2016 (Version 2.0) 3.0 Corporate Social Responsibility Statement October 2016 (Version 2.0) 9.1 Reefer Trailer defect reporting telephone number October 2016 (Version 2.0) 12.0 Reefer Trailer defect reporting telephone number. Dedicated Steel Coiler Fleet telephone number. October 2016 (Version 2.0) 14.0 Adding Website: http://www.poferrymasters.com/carrierinfo/health-and- safety/operational-standards/ October 2016 (Version 2.0) All sections Numbering amendments October 2016 (Version 2.0) 4.00 Updates to wording October 2016 (Version 2.0) 4.25 Loading Docks October 2016 (Version 2.0) 4.7 Driver Personal Protective Equipment October 2016 (Version 2.0) 4.10 Trucks and Vehicles – Handbrake Alarms October 2016 (Version 2.0) 12 Contacts table October 2016 (Version 2.0) 13 Novara and Oradea Rail Terminal addresses Version 2.0 2 1.0 Contents Table of Amendments ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.0 Contents ...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. -

101 Ltd • 101 Smart Limited • 1St Containers UK Ltd

The following companies sent delegations to Multimodal 2017:- 101 Ltd A R S Altmann UK 101 Smart Limited A R U P 1st Containers UK Ltd A S C Connections Birmingham 2 B P Ltd Ltd 2018 International Business A Safe UK Ltd Festival A V Dawson 2028 W Ltd A V Dawson Ltd 24-7 Recruitment Services Ltd A&R Solutions Ltd T/A Eps- 2MV Logistics Ltd European Parcel Services 3 T Logistics Ltd Hartrodt (UK) Ltd 3C Payment UK Ltd A.F.F. 3D Trans A2B 3D Trans Ltd A2B Online 3M A2B-Online Transport 3P Group Aardvark Marketing Consultants 3PL Ltd 3PL Real Estate Limited AB Enzymes GmbH 3rd Party Logistics Ltd AB Vista 3T Group Abel Systems 3T Logistics Aberdeen Asset Management 500 Logistics Limited ABF 7Seas Logistics Abingdon Risk Consulting A & S Recruitment Ltd Abloy UK A D M Milling Ltd ABM Data Systems A D M P Group Ltd ABML A E Yates Ltd ABN Amro Lease A I G Europe (UK) Ltd Abnormal Load Engineering Ltd A N L Above and Beyond PR A P L Aboveline A P L Logistics ABP ABP Group Aerfin Ltd ABP UK Aerial Giants Absorbopak Ltd Aerona Cca Ltd Accenture Afss Accenture Total Logistics AGA Rangemaster Group plc Access Delta Wms Aganto Access World A-Gas Access World (Europe) Agility Accolade Wines Agility Logistics Accord AHL/AFWW Ace Container Services AIG Europe Ltd Ace Express Freight Air & Cargo Services Ace Group Air Canada Ace Supplies UK Ltd Air Canada Cargo Acerinox UK Ltd Air Cargo Express Acmc Europe Ltd Air Cargo Express Australia ACN Europe Air Cargo News -

Impact of the Channel Tunnel: a Survey of Anglo-European Unitised Freight

This is a repository copy of Impact of the Channel Tunnel: A Survey of Anglo-European Unitised Freight. Results of the Phase II Interviews.. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/2115/ Monograph: Tweddle, G., Fowkes, A.S. and Nash, C.A. (1996) Impact of the Channel Tunnel: A Survey of Anglo-European Unitised Freight. Results of the Phase II Interviews. Working Paper. Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds , Leeds, UK. Working Paper 474 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Institute of Transport Studies University of Leeds This is an ITS Working Paper produced and published by the University of Leeds. -

Pets Travel Scheme

Assistance routes by sea and rail Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs / Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency Pet Travel Scheme Last updated: 21st March 2013 Routes may change and new ones may be added. See the PETS website or ring the Helpline 0870 241 1710 for the latest information. Some routes are seasonal or irregular so check availability and all your other proposed travel arrangements with the transport company before booking your journey to the UK. Check the costs, requirements and procedures. Companies may have their own additional conditions of travel. EU Routes by Sea Country From To Ferry Company Belgium Zeebrugge Southampton Cunard Line, P&O Cruises Zeebrugge Hull P&O Ferries Corsica Ajaccio Southampton P & O Cruises Denmark Copenhagen Southampton Cunard Line, P&O Cruises Esbjerg Harwich DFDS Seaways Estonia Tallin Southampton Cunard Line, P&O Cruises Finland Helsinki Southampton P&O Cruises France Brest Southampton P&O Cruises Caen Portsmouth Brittany FerriesFerries,, Calais Dover Hoverspeed P&O Ferries (may also accept foot passengers with guide and hearing dogs) and SeaFrance Calvi Southampton P&O Cruises (Assistance animals only) Cannes Southampton Cunard Line, P&O Cruises Cherbourg Plymouth Brittany Ferries Cherbourg Poole Brittany Ferries Cherbourg Portsmouth Brittany Ferries Cherbourg Southampton Cunard Line Dieppe Newhaven Hoverspeed (may also accept foot passengers with pets) This route operates in the Spring summer only) Dunkerque Dover Norfolkline Shipping La Rochelle Southampton Cunard