MIT Radiation Lab Series Vol. 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Army Radio Communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE

Army radio communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE Introduction Prior to the outbreak of WW1 in August 1914 many of the techniques to be used in later years for radio communications had already been invented, although most were still at an early stage of practical application. Radio transmitters at that time were predominantly using spark discharge from a high voltage induction coil, which created a series of damped oscillations in an associated tuned circuit at the rate of the spark discharge. The transmitted signal was noisy and rich in harmonics and spread widely over the radio spectrum. The ideal transmission was a continuous wave (CW) and there were three methods for producing this: 1. From an HF alternator, the practical design of which was made by the US General Electric engineer Ernst Alexanderson, initially based on a specification by Reginald Fessenden. These alternators were primarily intended for high-power, long-wave transmission and not suitable for use on the battlefield. 2. Arc generator, the practical form of which was invented by Valdemar Poulsen in 1902. Again the transmitters were high power and not suitable for battlefield use. 3. Valve oscillator, which was invented by the German engineer, Alexander Meissner, and patented in April 1913. Several important circuits using valves had been produced by 1914. These include: (a) the heterodyne, an oscillator circuit used to mix with an incoming continuous wave signal and beat it down to an audible note; (b) the detector, to extract the audio signal from the high frequency carrier; (c) the amplifier, both for the incoming high frequency signal and the detected audio or the beat signal from the heterodyne receiver; (d) regenerative feedback from the output of the detector or RF amplifier to its input, which had the effect of sharpening the tuning and increasing the amplification. -

HP 423A Crystal Detector

Errata Title & Document Type: 423A and 8470A Crystal Detector Operating and Service Manual Manual Part Number: 00423-90001 Revision Date: July 1976 About this Manual We’ve added this manual to the Agilent website in an effort to help you support your product. This manual provides the best information we could find. It may be incomplete or contain dated information, and the scan quality may not be ideal. If we find a better copy in the future, we will add it to the Agilent website. HP References in this Manual This manual may contain references to HP or Hewlett-Packard. Please note that Hewlett- Packard's former test and measurement, life sciences, and chemical analysis businesses are now part of Agilent Technologies. The HP XXXX referred to in this document is now the Agilent XXXX. For example, model number HP8648A is now model number Agilent 8648A. We have made no changes to this manual copy. Support for Your Product Agilent no longer sells or supports this product. You will find any other available product information on the Agilent Test & Measurement website: www.agilent.com Search for the model number of this product, and the resulting product page will guide you to any available information. Our service centers may be able to perform calibration if no repair parts are needed, but no other support from Agilent is available. OPERATING AND SERVICE MANUAL - I 423A 8470A CRYSTAL DETECTOR HEWLETT~PACKARD Plint.d: JUtY 191& e H.",len Packard Co. \910 1 " • .' • I .... ,. ", - \, . '. ~ ~.. ". ." , .' " . ..... " 'I. "",:,. • ' Page 2 i\lodel ·123A/8470A 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 10. -

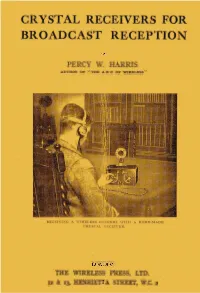

Crystal Receivers for Broadcast Reception

CRYSTAL RECEIVERS FOR BROADCAST RECEPTION BY PERCY W. HARRIS AUTH OR OF "THE A B C OF WIRELE SS " R E-C EI\·I~ G A \':I R EL l':': SS C c:' .''':CERT \\Tf1r :\ HO]\IE-l\[.-\DE C RYSTAL \;ECEI\ -EI~ LONDON THE WIRELESS PRESS, LTD. t 2 & I3, HENRIETTA STREET, w.e. 2 A HOME- MADE C R Y ST AL RECEIVER WITH ADJUSTME NTS F OR B R OADCAST 'NAVE-LE N GTHS A N D E I F F EL T OW E R TIME SI GN ALS. I N ST R UCTIONS FOR BUILDING T H I S S E T ARE G IVEN IN CHAP T E R X , CRYSTAL RECEIVERS FOR BROADCAST RECEPTION BY PERCY \Y HARIUS A UTHOR OF "THE A 13 C OF W I R ELESS," ETC. LOND ON THE WIRELESS PRESS, LTD. 1 2 & 13, HENRIETTA STREET, W.c. 2 NEW YORK: ,\VIlmLESS PRESS INC., 326 BIWADWAY THE WIRELESS PRESS, LTD. FOREIGN AND CO LOAIAL AGEiVCIES: SYDNEY, N.S.vV.: 97, Clarence Street. MELBOURNE: 422 (4, Little CoUins Street. MADRID: La Prensa Radiotelegrafica, 43, Calle de Alcala. GENOA: Agenzia Radiotelegrafica Italiana, Via Varese 3. AMSTERDAM: Nederlandsch Persbureau Radio, 562, Keizersgracht. INTRODUCTION THE advent of broadcast radio-telephony has aroused con siderable interest in the simple forms of wireless receiver, with the result that the crystal detector, \vhich was fast being ousted by the thermionic valve, has once again become popular. Numerous crystal receivers are now on the market, and the beginner in wireless may well feel some con fusion as to their merits. -

History of Diode

HISTORY OF DIODE In electronics, a diode is a two-terminal electronic component that conducts electric current in only one direction. The term usually refers to a semiconductor diode, the most common type today, which is a crystal of semiconductor connected to two electrical terminals, a P-N junction. A vacuum tube diode, now little used, is a vacuum tube with two electrodes; a plate and a cathode. The most common function of a diode is to allow an electric current in one direction (called the diode's forward direction) while blocking current in the opposite direction (the reverse direction). Thus, the diode can be thought of as an electronic version of a check valve. This unidirectional behavior is called rectification, and is used to convert alternating current to direct current, and extract modulation from radio signals in radio receivers. However, diodes can have more complicated behavior than this simple on-off action, due to their complex non-linear electrical characteristics, which can be tailored by varying the construction of their P-N junction. These are exploited in special purpose diodes that perform many different functions. Diodes are used to regulate voltage (Zener diodes), electronically tune radio and TV receivers (varactor diodes), generate radio frequency oscillations (tunnel diodes), and produce light (light emitting diodes). Diodes were the first semiconductor electronic devices. The discovery of crystals' rectifying abilities was made by German physicist Ferdinand Braun in 1874. The first semiconductor diodes, called cat's whisker diodes were made of crystals of minerals such as galena. Today most diodes are made of silicon, but other semiconductors such as germanium are sometimes used. -

EECS 117A Demonstration 2 Microwave Measurement Instruments

University of California, Berkeley Spring 2007 EECS 117 Prof. A. Niknejad EECS 117A Demonstration 2 Microwave Measurement Instruments NAME Introduction. Please review the general sinusoidal wave concepts in Secs. 3.1–3.9 of Inan & Inan. Note carefully Section 3.3. In this demonstration you will learn how to use a “50 ohm” slotted line, crystal detector, and standing wave ratio meter to obtain the wavelength λ and voltage standing wave ratio S on a coaxial transmission line. In a later demonstration you will use these techniques to measure and control impedances and reflection coefficients on a microwave transmission system. The apparatus used is shown below. The slotted line is a (rigid) continuation of the coaxial transmission lines “a” connected at each end. It has a thin slot in its outer conductor, cut along z. A probe rides within (but not touching) the slot to sample the transmission line voltage. The probe can be moved along z, and can also be moved into and out of the slot by means of a micrometer. The probe is connected to a crystal (diode) detector that converts the time-varying microwave voltage to dc. The dc voltage is measured using the standing wave ratio (SWR) meter. MICROMETER HP 415D b SWR METER DETECTOR TUNER HP 612 A UHF SIGNAL a TERMINATION GENERATOR a GR SLOTTED LINE POINT (LOAD) Z = 0 Z Suppose a sinusoidal voltage wave j(ωt−βz) v+(t) = Re hV+ e i (1) travels from the RF generator through the slotted line and is incident on a load (resistor, capacitor etc.) at z = 0. -

Methods for Topography Artifacts Compensation in Scanning Thermal Microscopy

Ultramicroscopy 155 (2015) 55–61 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ultramicroscopy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ultramic Methods for topography artifacts compensation in scanning thermal microscopy Jan Martinek a,c,n, Petr Klapetek a,b, Anna Charvátová Campbell a a Czech Metrology Institute, Okružní 31, 638 00 Brno, Czech Republic b CEITEC, BUT, Technická 3058/10, 616 00 Brno, Czech Republic c Department of Physics, Faculty of Civil Engineering, BUT, Žižkova 17, Brno 602 00, Czech Republic article info abstract Article history: Thermal conductivity contrast images in scanning thermal microscopy (SThM) are often distorted by Received 10 July 2014 artifacts related to local sample topography. This is pronounced on samples with sharp topographic Received in revised form features, on rough samples and while using larger probes, for example, Wollaston wire-based probes. The 8 April 2015 topography artifacts can be so high that they can even obscure local thermal conductivity variations Accepted 15 April 2015 influencing the measured signal. Three methods for numerically estimating and compensating for to- Available online 25 April 2015 pographic artifacts are compared in this paper: a simple approach based on local sample geometry at the Keywords: probe apex vicinity, a neural network analysis and 3D finite element modeling of the probe–sample Scanning thermal microscopy interaction. A local topography and an estimated probe shape are used as source data for the calculation Artifacts in all these techniques; the result is a map of false conductivity contrast signals generated only by sample Neural networks topography. This map can be then used to remove the topography artifacts from measured data or to estimate the uncertainty of conductivity measurements using SThM. -

The Crystal Radio

The Crystal Radio: An Inexpensive Form of Mass Communication Christopher Manxhari Massachusetts Academy of Math & Science at Worcester Polytechnic Institute Manxhari 1 Introduction Technology has always been developing, and with it so have methods and access to communication. One such example is the internet, which has been rapidly growing in the past years. Yet, despite all of these advancements, there is still a large population that lacks internet. During distraught times, such as the coronavirus pandemic, having access to information is important, but not everyone is able to access urgent information. Roughly 10% of the United States population does not have access to the internet (Anderson, Perrin, Jiang, & Kumar, 2020). This proportion translates to over 30 million United States citizens, which is quite a substantial population size. In fact, there appears to be a correlation between income level and the proportion of those in a certain economic bracket that have internet. At an annual income of less than $30,000, 18% of citizens lack access to the internet. Withal, 7% of those making between $30,000 and $50,000 annually, 3% of those making $50,000 to $75,000 annually, and 2% of those making anything upwards annually lack that access (Anderson et al., 2020). See Figure 1 for more data on the demographics of those using the internet. It is evident that one’s income level is positively correlated with higher frequencies of internet usage. The internet is but one of many mediums of mass communication, and it is certainly one dominating form. As of 2018, roughly 41% of U.S. -

Fabrication of Hot-Wire Probes and Electronics for Constant Temperature Anemometers

Latin American Applied Research 40:233-239(2010) FABRICATION OF HOT-WIRE PROBES AND ELECTRONICS FOR CONSTANT TEMPERATURE ANEMOMETERS O.D. OSORIO †, N. SILIN ‡ and J. CONVERTI § † Instituto Balseiro, S. C. de Bariloche, 8400, Argentina, e-mail: [email protected] ‡ Investigador CONICET, Instituto Balseiro, S. C. de Bariloche, 8400, Argentina, e-mail: [email protected] r § Instituto Balseiro, S. C. de Bariloche, 8400, Argentina, e-mail: [email protected] r Abstract −−−−−− The purpose of this paper is to discuss rior removal of the silver by chemical etching. the construction of constant temperature hot wire Electronics were built following the design of Its- anemometers. Different options are analyzed for the weire and Helland (1983) but including modifications to fabrication of sensors and electronics. A practical avoid the use of components not readily available, like and simple method is developed to manufacture the variable inductors and delay lines. probe and associated electronics. The fabricated sen- Frequency response was measured as suggested by sor has a diameter of 2 µm and approximately 500 Freymuth (1977) and Fingerson (1994). Measurements µm in length. The associated electronics are designed of a turbulent flow field were performed simultaneously to keep the sensor working at a constant tempera- with the present electronics and a commercial unit ture and allow the indirect measurement of speed. (TSI1051). The two measurements were equivalent for The design is simple, inexpensive and highly flexible frequencies up to approximately 50 kHz. regarding its use and modifications. The dynamic II. PROBE CONSTRUCTION tests performed and the comparison with a commer- Hot-wire probes are built with a thin wire of 0.5 to 20 cial model shows a satisfactory performance. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,177,422 B2 Kjoller Et Al

US008177422B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,177,422 B2 Kjoller et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 15, 2012 (54) TRANSITION TEMPERATURE (56) References Cited MICROSCOPY U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS (75) Inventors: Kevin Kjoller, Santa Barbara, CA (US); 6,185.992 B1* 2/2001 Daniels et al. ................ 25O?307 Khoren Sahagian, Burbank, CA (US); 6,200,022 B1* 3/2001 Hammiche et al. ............. 374/46 Doug Gotthard, Carpinteria, CA (US); gig3. R : S383 Airectalammiche et al. .............. (92.i Althy E" E. EcA 6,805,839 B2 * 10/2004 Cunningham et al. ... 422/82. 12 (US); Craig Prater, Santa Barbara, 7,448,798 B1 * 1 1/2008 Wang ..................... ... 374f183 (US); Roshan Shetty, Westlake Village, 2002/O126732 A1* 9, 2002 Shakouri et al. .............. 374,130 CA (US); Michael Reading, Norwich 2002/0196834 A1* 12/2002 Zaldivar et al. ................. 374,22 (GB) 2004/0026007 A1 2/2004 Hubert et al. ................... 156,64 2004/0202226 A1* 10, 2004 Gianchandani et al. ...... 374,185 2005/0105097 A1* 5/2005 Fang-Yen et al. ... 356,497 (73) Assignee: Anasys Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA 2006/0243034 A1 ck 11, 2006 Chand et al. T3/104 (US) 2007/0263696 A1* 11/2007 Kjoller et al. 374/31 2009 OO32706 A1* 2, 2009 Prater et al. 25O?307 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2009/0229020 A1* 9, 2009 Adams et al. ................... 850/33 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 SR A. 1939 CC. C. al . 3. U.S.C. 154(b) by 474 days. 2011/0078834 A1* 3/2011 King ................................ -

Pv-3 Globar Sensing Element

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title VAPOR-LIQUID EQUILIBRIA IN THE SYSTEM HYDROGEN-NITROGEN Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/836767dh Author Maimoni, Arturo. Publication Date 1955-09-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UCRL 3/3 I \ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA TWO-WEEK LOAN COPY This is a library Circulating Copy which may be borrowed for two weeks. For a personal retention copy, call Tech. Info. Diuision, Ext. 5545 BERKELEY. CALIFORNIA DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. UCRL-3131 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA I Radiation Laboratory Berkeley,. California Contract No. W -7405 -eng-48 . VAPOR-LIQUID EQUILIBRIA IN THE SYSTEM HYDROGEN -NITROGEN Arturo M.a.imoni (The sis) September 1, 1955 .·• Printed for the U. -

Advances in Scanning Thermal Microscopy Measurements for Thin Films

Chapter 1 Advances in Scanning Thermal Microscopy Measurements for Thin Films Liliana Vera-Londono, Olga Caballero-Calero, Jaime Andrés Pérez-Taborda and Marisol Martín-González Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.79961 Abstract One of the main challenges nowadays concerning nanostructured materials is the under- standing of the heat transfer mechanisms, which are of the utmost relevance for many specific applications. There are different methods to characterize thermal conductivity at the nanoscale and in films, but in most cases, metrology, good resolution, fast time acquisition, and sample preparation are the issues. In this chapter, we will discuss one of the most fascinating techniques used for thermal characterization, the scanning thermal microscopy (SThM), which can provide simultaneously topographic and thermal infor- mation of the samples under study with nanometer resolution and with virtually no sample preparation needed. This method is based on using a nanothermometer, which can also be used as heater element, integrated into an atomic force microscope (AFM) cantilever. The chapter will start with a historical introduction of the technique, followed by the different kinds of probes and operation modes that can be used. Then, some of the equations and heating models used to extract the thermal conductivity from these mea- surements will be briefly discussed. Finally, different examples of actual measurements performed on films will be shown. Most of these results deal with thermoelectric thin films, where the thermal conductivity characterization is one of the most important parameters to optimize their performance for real applications. Keywords: scanning thermal microscopy, thermal probes, thermoelectric thin films, thermal conductivity, local temperature measurements © 2018 The Author(s). -

Build a Crystal Radio: Electronics Series - Part I

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine General University of Maine Publications University of Maine Publications 1965 Build a Crystal Radio: Electronics Series - Part I University of Maine Cooperative Extension Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications Part of the Higher Education Commons, History Commons, and the Radio Commons Repository Citation University of Maine Cooperative Extension Service, "Build a Crystal Radio: Electronics Series - Part I" (1965). General University of Maine Publications. 286. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications/286 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in General University of Maine Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF MAINE LIBRARY COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE • UNIVERSITY OF MAINE, O r o n o ELECTRIC GUIDE SHEET OUTLINE A-21 (Advanced) BUILD A CRYSTAL RADIO ELECTRONICS SERIES - PART I lectronics is a fascinating hobby or a prof E itable lifetime occupation. Radio, apart of electronics, had its begin- ning about 1895 when Marconi succeeded in transmitting a "wireless" message over a distance of a mile and a half. Marconi did not invent radio, nor was he alone in its early work. However, from that small beginning radio has advanced until to- day its influence is felt in every phase of our lives. Through radio and television the world's greatest entertainers, educators, and poli ticians virtually step into our living room. Electronics provides communications across continents, oceans and into outer space.