Bosque Del Apache

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Kansas Biological Survey Report #151 Kelly Kindscher, Randy Jennings, William Norris, and Roland Shook September 8, 2008 Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Cover Photo: The Gila River in New Mexico. Photo by Kelly Kindscher, September 2006. Kelly Kindscher, Associate Scientist, Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, 2101 Constant Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66047, Email: [email protected] Randy Jennings, Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] William Norris, Associate Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Roland Shook, Emeritus Professor, Biology, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Citation: Kindscher, K., R. Jennings, W. Norris, and R. Shook. Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico. Open-File Report No. 151. Kansas Biological Survey, Lawrence, KS. ii + 42 pp. Abstract During 2006 and 2007 our research crews collected data on plants, vegetation, birds, reptiles, and amphibians at 49 sites along the Gila River in southwest New Mexico from upstream of the Gila Cliff Dwellings on the Middle and West Forks of the Gila to sites below the town of Red Rock, New Mexico. -

Resource Selection by an Ectothermic Predator in a Dynamic Thermal Landscape

Received: 2 May 2017 | Revised: 16 August 2017 | Accepted: 17 August 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.3440 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Resource selection by an ectothermic predator in a dynamic thermal landscape Andrew D. George1 | Grant M. Connette2 | Frank R. Thompson III3 | John Faaborg1 1Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA Abstract 2Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Predicting the effects of global climate change on species interactions has remained Front Royal, VA, USA difficult because there is a spatiotemporal mismatch between regional climate models 3U.S.D.A. Forest Service Northern Research and microclimates experienced by organisms. We evaluated resource selection in a Station, Columbia, MO, USA predominant ectothermic predator using a modeling approach that permitted us to Correspondence assess the importance of habitat structure and local real- time air temperatures within Andrew D. George, Department of Biology, Pittsburg State University, Pittsburg, KS USA. the same modeling framework. We radio- tracked 53 western ratsnakes (Pantherophis Email: [email protected] obsoletus) from 2010 to 2013 in central Missouri, USA, at study sites where this spe- cies has previously been linked to prey population demographics. We used Bayesian discrete choice models within an information theoretic framework to evaluate the sea- sonal effects of fine- scale vegetation structure and thermal conditions on ratsnake resource selection. Ratsnake resource selection was influenced most by canopy cover, canopy cover heterogeneity, understory cover, and air temperature heterogeneity. Ratsnakes generally preferred habitats with greater canopy heterogeneity early in the active season, and greater temperature heterogeneity later in the season. This sea- sonal shift potentially reflects differences in resource requirements and thermoregula- tion behavior. -

Pituophis Catenifer

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer Pacific Northwestern Gophersnake – P.c. catenifer Great Basin Gophersnake – P.C. deserticola Bullsnake – P.C. sayi in Canada EXTIRPATED - Pacific Northwestern Gophersnake – P.c. catenifer THREATENED - Great Basin Gophersnake – P.c. deserticola DATA DEFICIENT - Bullsnake – P.c. sayi 2002 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION DES ENDANGERED WILDLIFE IN ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: Please note: Persons wishing to cite data in the report should refer to the report (and cite the author(s)); persons wishing to cite the COSEWIC status will refer to the assessment (and cite COSEWIC). A production note will be provided if additional information on the status report history is required. COSEWIC 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 33 pp. Waye, H., and C. Shewchuk. 2002. COSEWIC status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-33 pp. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport du COSEPAC sur la situation de la couleuvre à nez mince (Pituophis catenifer) au Canada Cover illustration: Gophersnake — Illustration by Sarah Ingwersen, Aurora, Ontario. -

A Guide for Planning Riparian Treatments in New Mexico

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE A Guide for Planning Riparian Treatments in New Mexico United States Department of Agriculture New Mexico Natural Resources Conservation Service New Mexico Association of Conservation Districts NRCS Los Lunas Plant Materials Center September 2007 I. FOREWARD This guide has been prepared by the USDA New Mexico Natural Resources Conservation Service and the New Mexico Association of Conservation Districts, through funding for the restoration of riparian and watershed areas in the Pecos and Rio Grande Watersheds. The experiences of NRCS staff and Soil and Water Conservation Districts staff are reflected in the guide. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE II. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Foreward II. Table of Contents III. Introduction IV. Inventory, Analysis, and Design ................................................................................................1 Step 1 – Objective Step 2 – Obtaining Resource Data on the Site 1. Locate the Site 2. Soils Map and Interpretations 3. Climate 4. Hydrology 5. Channel Condition 6. Plants Present and Potential 7. Wildlife Habitat 8. Wildlife Depredation Step 3 – Analyze the Condition of the Riparian Area 1. Hydrologic Factors 2. Soils - Erosion and Deposition Factors 3. Vegetation Factors Step 4 – Design Considerations 1. Control of Invasive Woody Species and Subsequent Herbaceous Weeds 2. Streambank Stabilization 3. Channel Stabilization 4. Future Land Use 5. Management of Livestock and Wildlife Use 6. Planting Riparian Areas with Shallow Water Tables 7. Planting of Former Riparian Areas with Deep Water Tables 8. Criteria for Wildlife Habitat 9. Maintenance and Monitoring V. Planting Scenarios ......................................................................................................................17 1. Pond Vegetation Treatment 2. Pond Vegetation Treatment with Grass Seeding 3. Riverbank Willow Treatment on Sandy Soils 4. -

Loggerhead Shrike

EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: LOGGERHEAD SHRIKE Grasslands Ecosystem Initiative Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center U.S. Geological Survey Jamestown, North Dakota 58401 This report is one in a series of literature syntheses on North American grassland birds. The need for these reports was identified by the Prairie Pothole Joint Venture (PPJV), a part of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The PPJV recently adopted a new goal, to stabilize or increase populations of declining grassland- and wetland-associated wildlife species in the Prairie Pothole Region. To further that objective, it is essential to understand the habitat needs of birds other than waterfowl, and how management practices affect their habitats. The focus of these reports is on management of breeding habitat, particularly in the northern Great Plains. Suggested citation: Dechant, J. A., M. L. Sondreal, D. H. Johnson, L. D. Igl, C. M. Goldade, M. P. Nenneman, A. L. Zimmerman, and B. R. Euliss. 1998 (revised 2002). Effects of management practices on grassland birds: Loggerhead Shrike. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND. 19 pages. Species for which syntheses are available or are in preparation: American Bittern Grasshopper Sparrow Mountain Plover Baird’s Sparrow Marbled Godwit Henslow’s Sparrow Long-billed Curlew Le Conte’s Sparrow Willet Nelson’s Sharp-tailed Sparrow Wilson’s Phalarope Vesper Sparrow Upland Sandpiper Savannah Sparrow Greater Prairie-Chicken Lark Sparrow Lesser Prairie-Chicken Field Sparrow Northern Harrier Clay-colored Sparrow Swainson’s Hawk Chestnut-collared Longspur Ferruginous Hawk McCown’s Longspur Short-eared Owl Dickcissel Burrowing Owl Lark Bunting Horned Lark Bobolink Sedge Wren Eastern Meadowlark Loggerhead Shrike Western Meadowlark Sprague’s Pipit Brown-headed Cowbird EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: LOGGERHEAD SHRIKE Jill A. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/06/2021 09:29:00AM Via Free Access 42 Luiselli Et Al

Contributions to Zoology, 74 (1/2) 41-49 (2005) Analysis of a herpetofaunal community from an altered marshy area in Sicily; with special remarks on habitat use (niche breadth and overlap), relative abundance of lizards and snakes, and the correlation between predator abundance and tail loss in lizards Luca Luiselli1, Francesco M. Angelici2, Massimiliano Di Vittorio3, Antonio Spinnato3, Edoardo Politano4 1 F.I.Z.V. (Ecology), via Olona 7, I-00198 Rome, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] 2 F.I.Z.V. (Mammalogy), via Cleonia 30, I-00152 Rome, Italy. 3 Via Jevolella 2, Termini Imprese (PA), Italy. 4 Centre of Environmental Studies ‘Demetra’, via Tomassoni 17, I-61032 Fano (PU), Italy Abstract relationships, thus rendering the examination of the relationships between predators and prey an extreme- A field survey was conducted in a highly degraded barren en- ly complicated task for the ecologist (e.g., see Con- vironment in Sicily in order to investigate herpetofaunal com- nell, 1975; May, 1976; Schoener, 1986). However, munity composition and structure, habitat use (niche breadth and there is considerable literature (both theoretical and overlap) and relative abundance of a snake predator and two spe- empirical) indicating that case studies of extremely cies of lizard prey. The site was chosen because it has a simple community structure and thus there is potentially less ecological simple communities, together with the use of appropri- complexity to cloud any patterns observed. We found an unexpect- ate minimal models, can help us to understand the edly high overlap in habitat use between the two closely related basis of complex patterns of ecological relationships lizards that might be explained either by a high competition for among species (Thom, 1975; Arditi and Ginzburg, space or through predator-mediated co-existence i.e. -

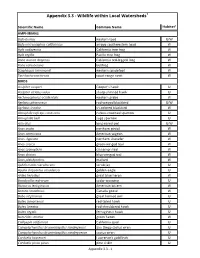

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife Within Local Watersheds1

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife within Local Watersheds1 2 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat AMPHIBIANS Bufo boreas western toad U/W Bufo microscaphus californicus arroyo southwestern toad W Hyla cadaverina California tree frog W Hyla regilla Pacific tree frog W Rana aurora draytonii California red-legged frog W Rana catesbeiana bullfrog W Scaphiopus hammondi western spadefoot W Taricha torosa torosa coast range newt W BIRDS Accipiter cooperi Cooper's hawk U Accipiter striatus velox sharp-shinned hawk U Aechmorphorus occidentalis western grebe W Agelaius phoeniceus red-winged blackbird U/W Agelaius tricolor tri-colored blackbird W Aimophila ruficeps canescens rufous-crowned sparrow U Aimophilia belli sage sparrow U Aiso otus long-eared owl U/W Anas acuta northern pintail W Anas americana American wigeon W Anas clypeata northern shoveler W Anas crecca green-winged teal W Anas cyanoptera cinnamon teal W Anas discors blue-winged teal W Anas platrhynchos mallard W Aphelocoma coerulescens scrub jay U Aquila chrysaetos canadensis golden eagle U Ardea herodius great blue heron W Bombycilla cedrorum cedar waxwing U Botaurus lentiginosus American bittern W Branta canadensis Canada goose W Bubo virginianus great horned owl U Buteo jamaicensis red-tailed hawk U Buteo lineatus red-shouldered hawk U Buteo regalis ferruginous hawk U Butorides striatus green heron W Callipepla californica California quail U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegensis San Diego cactus wren U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegoense cactus wren U Carduelis lawrencei Lawrence's -

For Creative Minds

For Creative Minds The For Creative Minds educational section may be photocopied or printed from our website by the owner of this book for educational, non-commercial uses. Cross-curricular teaching activities, interactive quizzes, and more are available online. Go to www.ArbordalePublishing.com and click on the book’s cover to explore all the links. Diurnal or Nocturnal Animals that are active during the day and asleep at night are diurnal. Animals that are active at night and asleep during the day are nocturnal. Read the following sentences and look for clues to determine if the animal is diurnal or nocturnal. A large dog sneaks up on The garter snake passes the skunk in the dark of the morning hunting night. The skunk stamps and basking in the warm her feet and throws her sunlight. If a predator tail up in the air. She arrives, he will hide his gives the other animal a head under some leaves warning before spraying. and flail his tail until it goes away. This bluebird is a The bright afternoon sun helpful garden bird. He helps this high-flying spends his days eating red-tailed hawk search insects off the plants and for her next meal. She defending his territory can see a grasshopper from other birds. from more than 200 feet (61m) away! As night falls, a small, The barn owl sweeps flying beetle with a over the field under glowing abdomen the dark night sky. emerges. She flashes her He flies slowly and light to signal to other silently, scanning the fireflies to come out. -

Roadrunner Fact Sheet

Roadrunner Fact Sheet Common Name: Roadrunner Scientific Name: Geococcyx Californianus & Geococcyx Velox Wild Status: Not Threatened Habitat: Arid dessert and shrub Country: United States, Mexico, and Central America Shelter: These birds nest 1-3 meters off the ground in low trees, shrubs, or cactus Life Span: 8 years Size: 2 feet in length; 8-15 ounces Details The genus Geococcyx consists of two species of bird: the greater roadrunner and the lesser roadrunner. They live in the arid climates of Southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America. Though these birds can fly, they spend most of their time running from shrub to shrub. Roadrunners spend the entirety of their day hunting prey and dodging predators. It's a tough life out there in the wild! These birds eat insects, small reptiles and mammals, arachnids, snails, other birds, eggs, fruit, and seeds. One thing that these birds do not have to worry about is drinking water. They intake enough moisture through their diet and are able to secrete any excess salt build-up through glands in their eyes. This adaptation is common in sea birds as their main source of hydration is the ocean. The fact that roadrunners have adapted this trait as well goes to show how well they are suited for their environment. A roadrunner will mate for life and will travel in pairs, guarding their territory from other roadrunners. When taking care of the nest, both male and female take turns incubating eggs and caring for their young. The young will leave the nest after a couple weeks and will then learn foraging techniques for a few days until they are left to fend for themselves. -

Fuels Reduction and Restoration in the Bosque of the Middle Rio Grande

By applying treatments, the team worked to restore New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande bosque, the most extensive, remaining cottonwood forest in the Southwest. Photo by USDA Forest Service. Pentimento: Fuels Reduction and Restoration in the Bosque of the Middle Rio Grande Summary The Middle Rio Grande of New Mexico is the most extensive, remaining bosque, or cottonwood forest in the southwest. Alterations caused by humans—damming and channeling the river, controlling floods, and planting non-native trees—have disrupted the cycles of the earlier ecosystem. Without periodic flooding, native cottonwoods cannot regenerate. Invasive exotic plants such as Tamarisk, also known as salt cedar, and Russian olive have filled in the gaps and open spaces, increased fuel loads, and continue to replace native trees and shrubs after wildfires. Cottonwoods, not a fire-adapted species, are now at risk from wildfire and replacement by invasive plants. An array of fuel treatments applied to study sites reduced invasive woody plants in the bosque. Resprout rates for exotic trees were low overall. Survival rates of transplanted native plant species were high. Restoration had various effects on birds, animals, amphibians, and reptiles of the bosque. Species that prefer a more open, less-cluttered habitat benefited, and their numbers increased. Species that prefer a closed, shrubbier habitat altered by invasives declined. Fire Science Brief Issue 7 April 2008 Page 1 www.firescience.gov Key Findings • Treatments reduced fuel loads, which will save native trees not adapted to fire from burning in fire. • Treatments, such as deep mulch, reduced the ability of invasive plants to regrow. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. | http://redlist-ARC.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47.